Bamileke people

Pe me leke | |

|---|---|

King of Bandjoun, one of the numerous Bamileke Kingdoms in Cameroon | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 8,000,000 est. [1][1] | |

| Languages | |

| Bamileke Languages, French | |

| Religion | |

| Grassfields beliefs and ancestral worship (dual system: Divinities-based, and Ancestors-based), Christianity, Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tikar, Bamum, other Grassfields peoples | |

The Bamileke are a Central African people who inhabit the Bamenda Grassfields of Cameroon. They speak a Southern Bantoid language within the Bamileke language group.[2]

Languages

The Bamileke speak a language belonging to the Grassfields branch of the Benue-Congo branch of the Niger-Congo language family.[3] Grassfields languages belong to a branch within Niger-Congo sometimes labelled "Bantuoid" which is related to the Bantu branch of Niger-Congo, with both deriving from a common ancestor which originated in or near the Cameroon region between 3,000 and 2,500[4][5] or 5,000 years ago.[6]

History

The Bamileke are said to have entered their current location from the Mbam region further north,[2][better source needed] They were originally known as the Dschang people who referred to themselves as Baliku. Bamileke is thought to be a colonial corruption of their original names.[7] They were later joined by the Tikar, Bali, Bamum and Bafia peoples, who migrated into their current region of Cameroon. This accounts for the use of the title Fon by all five of the ethnic groups. Like a king, the Fon is head of all authorities, from territory to civil and military, within a given kingdom.[8]

In the 17th century, the Bamileke migrated further south and west under the pressure of the Fulani people.[9] When Cameroon was colonized, the British granted status and a certain amount of control to traditional authorities, such as the Fon. This was due to a colonial policy known as indirect rule. On the other hand, the Germans and French looked at Fons with contempt and were often suspicious of them.[8]

According to research compiled in The Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon, the "Bamiléké have a reputation of being excellent farmers and businessmen and -women. While they have become a significant factor in the national economy, their success has also generated some jealousy and resentment, especially among the original inhabitants of areas to which Bamiléké migration has occurred."[8] This led to many Fulani leading raids against the Bamileke, who were often sold by the Fulani into slavery in the Atlantic slave trade.[2] Today, a number of Black people across the Americas, such as Erykah Badu and Jessica Williams, can trace their lineage back to the Bamileke people through genetic testing.

Resentment for enslavement and slave trading lingered and led to the 1967 Tombel Massacre, where over 230 Bamileke are believed to have been murdered by the neighboring Bakossi people.[8]

Lifestyle and settlement patterns

Political structure and agriculture

Bamileke settlements follow a well-organized and structured pattern. Houses of family members are often grouped together and surrounded by small fields. Men typically clear the fields, but it is largely women who work them. Most work is done with tools such as machetes and hoes. Staple crops include cocoyams, groundnuts and maize.[2]

Bamileke settlements are organized as chiefdoms. The chief, or fon or fong is considered as the spiritual, political, judicial and military leader. The chief is also considered as the 'father' of the chiefdom. He thus has great respect from the population. The successor of the 'father' is chosen among his children. The successor's identity is typically kept secret until the fon's death.[3]

The fon typically has 9 ministers and several other advisers and councils. The ministers are in charge of the crowning of the new fon. The council of ministers, also known as the Council of Notables, is called Kamveu. In addition, a "queen mother" or mafo was an important figure for some fons in the past. Below the fon and his advisers lie a number of ward heads, each responsible for a particular portion of the village. Some Bamileke groups also recognize sub-chiefs, or fonte.[3]

Economic activities

Traditional homes are constructed by first erecting a raffia-pole frame into four square walls. Builders then stuff the resulting holes with grass and cover the whole building with mud. The thatched roof is typically shaped into a tall cone.[3] In the present day, however, this type of construction is mostly reserved for barns, storage buildings, and gathering places for various traditional secret societies.[2] Instead, modern Bamileke homes are made of bricks of either sun-dried mud or of concrete. Roofs are usually made of metal sheeting.

Religious beliefs

During the colonial period, parts of the Bamileke region adopted Christianity, though some of them practice Islam. Today, the dominant form of worship is still ancestral with most Bamileke practicing Veneration of the dead.[2] Death is always met with mystery, and the family is required to turn the body over to an examiner to determine the cause of death. After this is completed, the family must gather at the home. Each member must step up to the totem and swear that they were not involved in the death of the loved one. It is believed that if someone in the room really is the murderer, the totem will trap their spirit forever. To satisfy the Ancestors, the person believed to be a murderer must perform a special ritual that consists of the pouring out of libation during the burial ceremony. The family will then gather the wet earth and shape it into a circle. This is seen as a metaphorical skull of the deceased, blessed by libation.[7]

The Bamileke also believe that the Ancestor's spirit still remains within the actual skulls of the Ancestors as well, so they keep possession of them. The oldest male in the family keeps the skulls of both male and female ancestors in a dwelling that the family built and a diviner has blessed. In the event that a skull is not well preserved, a special ritual must be performed that consists of the pouring out of libation.[2]

The Bamileke are known for elaborate elephant masks used in dance ceremonies or funerals to show the importance of the deceased person. During the homegoing celebration of King Njoya's mother in 1913, elephant masks were worn by those in attendance.[7]

Royal Tradition and the Arts

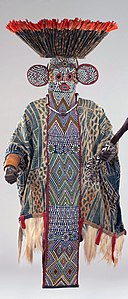

Masquerades are an integral part of Bamileke culture and expression. Colorful, beaded masks are donned at special events such as funerals, important palace festivals and other royal ceremonies. The masks are performed by men and aim to support and enforce royal authority.[10]

The power of a Bamileke king, called a Fon, is often represented by the elephant, buffalo, and leopard. Oral traditions proclaim that the Fon may transform into either an elephant or leopard whenever he chooses. An elephant mask, called a mbap mteng, has protruding circular ears, a human-like face, and decorative panels on the front and back that hang down to the knees and are covered overall in beautiful geometric beadwork, including triangular imagery. Isosceles triangles are prevalent, as they are the known symbol of the leopard.[11] Beadwork, shells, bronze, and other precious embellishments on masks elevate the mask's status.[10] On occasion, a Fon may permit members of the community to perform in an elephant mask along with a leopard skin, indicating a statement of wealth, status, and power being associated with this masquerade.[11]

Buffalo masks are also very popular and present at most functions throughout Grassland societies, including the Bamileke. They represent power, strength and bravery, and may also be associated with the Fon.[12]

Beadwork

Beadwork is an essential element of Bamileke art and distinguishes it from other regions of Africa. It is an art form that is highly personal in that no two pieces are alike and are often used in dazzling colors that catch the eye. They may be an indication of status based on what kinds of beads are used. Beadwork utilized all over on wooden sculptures is a technique that is unique only to the Cameroon grasslands.[13]

Before they were colonized, popular beads were obtained from Sub-Saharan countries like Nigeria and were made of shells, nuts, wood, seeds, ceramic, ivory, animal bone, and metal. Colonization and trade routes with other countries in Europe and the Middle East introduced brightly colored glass beads as well as pearls, coral and rare stones like emeralds. These came at a price, however. There were often agreements with these other countries to exchange these precious luxury commodities for slaves, gold, oil, ivory and some types of fine woods.[13]

Succession and kinship patterns

The Bamileke trace their ancestry, inheritance and succession through the male line, and children belong to the fondom of their father. After a man's death, all of his possessions typically go to a single, male heir. Polygamy (more specifically, polygyny) is practiced, and some important individuals may have literally hundreds of wives. Marriages typically involve a bride price to be paid to the bride's family.

It is argued that the Bamileke inheritance customs contributed to their success in the modern world:

"Succession and inheritance rules are determined by the principle of patrilineal descent. According to custom, the eldest son is the probable heir, but a father may choose any one of his sons to succeed him. An heir takes his dead father's name and inherits any titles held by the latter, including the right to membership in any societies to which he belonged. And, until the mid-1960s, when the law governing polygamy was changed, the heir also inherited his father's wives--a considerable economic responsibility. The rights in land held by the deceased were conferred upon the heir subject to the approval of the chief, and, in the event of financial inheritance, the heir was not obliged to share this with other family members. The ramifications of this are significant. First, dispossessed family members were not automatically entitled to live off the wealth of the heir. Siblings who did not share in the inheritance were, therefore, strongly encouraged to make it on their own through individual initiative and by assuming responsibility for earning their livelihood. Second, this practice of individual responsibility in contrast to a system of strong family obligations prevented a drain on individual financial resources. Rather than spend all of the inheritance maintaining unproductive family members, the heir could, in the contemporary period, utilize his resources in more financially productive ways such as for savings and investment. [...] Finally, the system of inheritance, along with the large-scale migration resulting from population density and land pressures, is one of the internal incentives that accounts for Bamileke success in the nontraditional world".[14]

Donald L. Horowitz also attributes the economic success of the Bamileke to their inheritance customs, arguing that it encouraged younger sons to seek their own living abroad. He wrote in Ethnic groups in conflict: "Primogeniture among the Bamileke and matrilineal inheritance among the Minangkabau of Indonesia have contributed powerfully to the propensity of males from both groups to migrate out of their home region in search of opportunity".[15]

Notable Individuals

Here is a list of notable Bamileke or people of Bamileke descent.

- Benoît Angbwa

- Christ Mbondi

- Frank Tsadjout

- Patrice Nganang, writer and professor of Africana

- Erykah Badu, American singer-songwriter, record producer and actress

- Jessica Williams, American actress and comedienne

- Adrian Awasom, American football player

- Joao Maleck

- Julius Akosah, Cameroonian soccer player

- Ndamukong Suh, American football player

- Samuel Eto'o

- Samuel Umtiti

- Timothée Atouba, Cameroonian soccer player

- Maurice Kamto, former president of the UN International Law Commission, international lawyer, professor[16]

- Victor Fotso, industrialist[17]

- Sam Fan Thomas, Makossa musician

- Ernest Ouandié, independence fighter

- Kadji Defosso, industrialist[18]

- Mathias Djoumessi, president of the UPC political party[19]

- Wilgory Tanjong, entrepreneur and author[20]

Gallery

-

Stool used by notables of the Fon's (kings) of the Bamileke court

-

Elaborate Mask Ensemble of the Kuosi Society

-

Traditional Bamileke architecture, depicting impressive wooden structures. Remnants of Bamileke civilisation

-

Traditional Bamileke architecture, the Bandjoun palace

-

A modern building replicating portions of Bamileke architecture. Zingana Hotel, Bafoussam

-

Young men wearing traditional Bamileke attire during a marriage ceremony

Bamileke Dance Groups

-

"Clan Age" dance

References

- ^ "Bantu, Cameroon-Bamileke". Joshua Project. Retrieved 7 February 2019. Includes other non-Bamileke Semi-Bantu people.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Bamileke - Art & Life in Africa - The University of Iowa Museum of Art". africa.uima.uiowa.edu. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ a b c d "Bamileke | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2011). "'The membership and internal structure of Bantoid and the border with Bantu" (PDF). Berlin: Humboldt University. pp. 28, 30.

- ^ Derek Nurse & Gérard Philippson, 2003, The Bantu Languages, p 227

- ^ Newman (1995), Shillington (2005)

- ^ a b c Asante, Molefi Kete, Molefi Kete (2008). The Encyclopedia of African Religion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. p. 102. ISBN 978-1412936361.

- ^ a b c d DeLancey, Mark Dike; Neh Mbuh, Rebecca; DeLancey, Mark W. (2010). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 166, 365, 366. ISBN 978-0810837751.

- ^ "Bamileke | people".

- ^ a b Perani, Judith (1998). The visual arts of Africa : gender, power, and life cycle rituals. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 215. ISBN 0-13-442328-3. OCLC 605230100.

- ^ a b Pemberton III, John (2008). African Beaded Art: Power and Adornment. Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College Museum of Art. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-0-87391-058-3.

- ^ Geary, Christraud (2008). Cameroon: Art and Kings. Museum Reitberg Zurich: Museum Reitberg Zurich. p. 183. ISBN 978-3-907077-35-1.

- ^ a b Pemberton III, John (2008). African Beaded Art: Power and Adornment. Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College Museum of Art. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-87391-058-3.

- ^ A.I.D. Evaluation Special Study No. 15 THE PRIVATE SECTOR: - Individual Initiative, And Economic Growth In An African Plural Society The Bamileke Of Cameroon http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnaal016.pdf

- ^ Horowitz, Donald L.; Donald, Horowitz L.; Horowitz, Professor Donald L. (1985). Ethnic Groups in Conflict. University of California Press. p. 155. ISBN 9780520053854.

- ^ "Maurice Kamto", Wikipedia, 2020-06-07, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ "Victor Fotso", Wikipedia, 2020-05-15, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ "Joseph Kadji Defosso", Wikipédia (in French), 2020-04-15, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ "Mathias Djoumessi", Wikipédia (in French), 2020-05-11, retrieved 2020-06-08

- ^ "Wilglory Tanjong | Department of African American Studies". aas.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2016; first ed. 2010), Histoire et anthropologie du peuple bamiléké, Paris: l’Harmattan, 2010, 338p.

- Toukam, Dieudonné (2008), Parlons bamiléké. Langue et culture de Bafoussam, Paris: L'Harmattan, 255p.

- Fanso, V.G. (1989) Cameroon History for Secondary Schools and Colleges, Vol. 1: From Prehistoric Times to the Nineteenth Century. Hong Kong: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1989.

- Neba, Aaron, Ph.D. (1999) Modern Geography of the Republic of Cameroon, 3rd ed. Bamenda: Neba Publishers, 1999.

- Ngoh, Victor Julius (1996) History of Cameroon Since 1800. Limbé: Presbook, 1996.

Further reading

- Knöpfli, Hans (1997—2002) Crafts and Technologies: Some Traditional Craftsmen and Women of the Western Grassfields of Cameroon. 4 vols. Basel, Switzerland: Basel Mission.

External links

- Aleco Yemba.net - Online Dictionaries and Learning Tools for the Yemba Language

- Works by Bamileke artists at the University of Michigan Museum of Art

- Bamileke art at the University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art

- Works by Bamileke artists at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Works by Bamileke artists at the Brooklyn Museum