Biceps

| Biceps brachii | |

|---|---|

Location | |

| Details | |

| Origin | short head: coracoid process of the scapula. long head: supraglenoid tubercle |

| Insertion | radial tuberosity and bicipital aponeurosis into deep fascia on medial part of forearm |

| Artery | brachial artery |

| Nerve | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5–C6) |

| Actions | flexes elbow and supinates forearm |

| Antagonist | Triceps brachii muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus biceps brachii |

| TA98 | A04.6.02.013 |

| TA2 | 2464 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

In human anatomy, the biceps brachii, or simply biceps in common parlance, is, as the name implies, a two-headed muscle. The biceps lie on the upper arm between the shoulder and the elbow. Both heads arise on the scapula and join to form a single muscle belly which is attached to the upper forearm. While the biceps crosses both the shoulder and elbow joints, its main function is at the latter where it flexes the elbow and supinates the forearm. Both these movements are used when opening a bottle with a corkscrew: first biceps unscrews the cork (supination), then it pulls the cork out (flexion). [1]

Terminology

The term biceps brachii is a Latin phrase meaning "two-headed [muscle] of the arm", in reference to the fact that the muscle consists of two bundles of muscle, each with its own origin, sharing a common insertion point near the elbow joint. The proper plural form of the Latin adjective biceps is bicipites, a form not in general English use. Instead, biceps is used in both singular and plural (i.e., when referring to both arms).

The English form bicep [sic], attested from 1939, is a back formation derived from interpreting the s of biceps as the English plural marker -s.[2][3] While common even in professional contexts, it is often considered incorrect.[4]

The biceps brachii muscle is the one that gave all muscles their name: it comes from the Latin musculus, "little mouse", because the appearance of the flexed biceps resembles the back of a mouse. The same phenomenon occurred in Greek, in which μῦς, mȳs, means both "mouse" and "muscle".

Human anatomy

Origin and insertion

Proximally (towards the body), the short head of the biceps originates from the coracoid process at the top of the scapula. The long head originates from the supraglenoid tubercle just above the shoulder joint from where its tendon passes down along the intertubercular groove of the humerus into the joint capsule of the shoulder joint. [1] When the humerus is in motion, the tendon of the long head is held firmly in place in the intertubercular groove by the greater and lesser tubercles and the overlying transverse humeral ligament. During the motion from external to internal rotation, the tendon is forced medially against the lesser tubercle and superiorly against the transverse ligament. [5]

Both heads join on the middle of the humerus, usually near the insertion of the deltoid, to form a common muscle belly. Distally (towards the fingers), biceps ends in two tendons: the stronger attaches to (inserts into) the radial tuberosity on the radius, while the other, the bicipital aponeurosis, radiates into the ulnar part of the antebrachial fascia. [6]

Two additional muscles lie underneath the biceps brachii. These are the coracobrachialis muscle, which like the biceps attaches to the coracoid process of the scapula, and the brachialis muscle which connects to the ulna and along the mid-shaft of the humerus. Besides those, the brachioradialis muscle is adjacent to the biceps and also inserts on the radius bone, though more distally.

Variation

Traditionally described as a two-headed muscle, biceps brachii is one of the most variable muscles of the human body and has a third head arising from the humerus in 10% of cases (normal variation) — most commonly originating near the insertion of the coracobrachialis and joining the short head — but four, five, and even seven supernumerary heads have been reported in rare cases. [7] The distal biceps tendons are completely separated in 40% and bifurcated in 25% of cases. [8]

Innervation

Biceps brachii is innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve together with coracobrachialis and brachialis; like the latter, from fibers of the fifth and sixth cervical nerves. [9]

Functions

The biceps is tri-articulate, meaning that it works across three joints.[10] The most important of these functions is to supinate the forearm and flex the elbow.

These joints and the associated actions are listed as follows in order of importance:[11]

- Proximal radioulnar joint (upper forearm) – Contrary to popular belief, the biceps brachii is not the most powerful flexor of the forearm, a role which actually belongs to the deeper brachialis muscle. The biceps brachii functions primarily as a powerful supinator of the forearm (turns the palm upwards). This action, which is aided by the supinator muscle, requires the elbow to be at least partially flexed. If the elbow, or humeroulnar joint, is fully extended, supination is then primarily carried out by the supinator muscle.

- Humeroulnar joint (elbow) – The biceps brachii also functions as an important flexor of the forearm, particularly when the forearm is supinated. Functionally, this action is performed when lifting an object, such as a bag of groceries or when performing a biceps curl. When the forearm is in pronation (the palm faces the ground), the brachialis, brachioradialis, and supinator function to flex the forearm, with minimal contribution from the biceps brachii.

- Glenohumeral joint (shoulder) – Several weaker functions occur at the glenohumeral, or shoulder, joint. The biceps brachii weakly assists in forward flexion of the shoulder joint (bringing the arm forward and upwards). It may also contribute to abduction (bringing the arm out to the side) when the arm is externally (or laterally) rotated. The short head of the biceps brachii also assists with horizontal adduction (bringing the arm across the body) when the arm is internally (or medially) rotated. Finally, the long head of the biceps brachii, due to its attachment to the scapula (or shoulder blade), assists with stabilization of the shoulder joint when a heavy weight is carried in the arm.

Training

The biceps can be strengthened using weight and resistance training. An example of a well known biceps exercise is the simple biceps curl.

Evolutionary variation

In Neanderthals, the radial bicipital tuberosities were larger than in modern humans, which suggests they were probably able to use their biceps for supination over a wider range of pronation-supination. It is possible that they relied more on their biceps for forceful supination without the assistance of the supinator muscle like in modern humans, and thus that they used a different movement when throwing. [12]

In the horse, the biceps' function is to extend the shoulder and flex the elbow. It is composed of two short-fibred heads separated longitudinally by a thick internal tendon which stretches from the origin on the supraglenoid tubercle to the insertion on the medial radial tuberosity. This tendon is capable to withstand very large forces when the biceps is stretched. From this internal tendon a strip of tendon, the lacertus fibrosus, connects the muscle with the extensor carpi radialis -- an important feature in the horse's stay apparatus (through which the horse can rest and sleep whilst standing.) [13]

Additional images

-

Diagram of the human shoulder joint

-

Left scapula. Dorsal surface

-

Glenoid fossa of right side. Tendon of long head labelled

-

Left shoulder joint. Tendon of long head labelled E

-

Bones of left forearm. Anterior aspect

-

Cross-section through the middle of upper arm

-

Front of the left forearm. Superficial muscles

-

The brachial artery

-

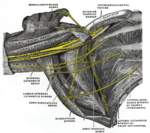

The right brachial plexus (infraclavicular portion) in the axillary fossa; viewed from below and in front

-

Nerves of the left upper extremity

-

Biceps brachialis muscle

-

Biceps brachial muscle

-

Biceps brachii muscle

-

Biceps brachii muscle

-

Biceps brachii muscle

-

Biceps brachii muscle

-

Biceps brachii muscle

-

Biceps brachii muscle

-

Biceps brachialis muscle

-

Biceps brachialis muscle

-

Biceps brachialis muscle

-

Biceps brachialis muscle

-

Biceps brachialis muscle

References

- ^ a b Lippert, Lynn S. (2006). Clinical kinesiology and anatomy (4th ed.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company. pp. 126–7. ISBN 978-0-8036-1243-3.

- ^ "Bicep". Dictionary and Thesaurus — Merriam-Webster Online. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ^ Arnold Zwicky (July 30, 2008). "The dangers of satire". Language Log. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ^ Tangled Passages, Corbett, Philip B., February 9, 2010, The New York Times

- ^ Cone, Robert 0; Danzig, Larry; Resnick, Donald; Goldman, Amy Beth (1983). "The Bicipital Groove: Radiographic, Anatomic, and Pathologic Study" (PDF). American Journal of Roentgenology. 141 (4): 781–788.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. p. 154. ISBN 1-58890-159-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Poudel, PP; Bhattarai, C (2009). "Study on the supernumerary heads of biceps brachii muscle in Nepalese" (PDF). Nepal Med Coll J. 11 (2): 96–98.

- ^ Dirim, Berna; Brouha, Sharon Sudarshan; Pretterklieber, Michael L; Wolff, Klaus S (2008). "Terminal Bifurcation of the Biceps Brachii Muscle and Tendon: Anatomic Considerations and Clinical Implications" (PDF). American Journal of Roentgenology. 191 (6): W248–W255. doi:10.2214/AJR.08.1048.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Gray's Anatomy (1918), see infobox

- ^ "Biceps Brachii". ExRx.net. Retrieved March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Simons David G., Travell Janet G., Simons Lois S. (1999). "30: Biceps Brachii Muscle". In Eric Johnson (ed.). Travell & Simons' Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction (2nd ed.). Baltimore, Maryland: Williams and Wilkins. pp. 648–659. ISBN 0-683-08363-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Churchill, SE; Rhodes, JA (2009). "Fossil Evidence for Projectile Weaponry". In Hublin, Jean-Jacques (ed.). The evolution of hominin diets: integrating approaches to the study of Palaeolithic subsistence. Springer. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4020-9698-3.

- ^ Watson, JC; Wilson, AM (2007). "Muscle architecture of biceps brachii, triceps brachii and supraspinatus in the horse". J Anat. 210 (1): 32–40. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00669.x. PMC 2100266. PMID 17229281.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- "Biceps brachii muscle". GPnotebook.

- Anatomy photo:06:05-0102 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center