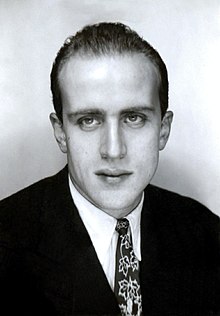

Boris Vian

Boris Vian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 10 March 1920 Ville-d'Avray, Hauts-de-Seine, France |

| Died | 23 June 1959 (aged 39) Paris, France |

| Pen name | Vernon Sullivan, Bison Ravi, Baron Visi, Brisavion |

| Occupation | Novelist, playwright, journalist, engineer, musician, songwriter, singer |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École Centrale Paris |

| Notable works | L'Écume des jours J'irai cracher sur vos tombes L'Automne à Pékin L'Herbe rouge L'Arrache-coeur |

| Website | |

| borisvian | |

Boris Vian (French: [bɔʁis vjɑ̃]; 10 March 1920 – 23 June 1959) was a French polymath: writer, poet, musician, singer, translator, critic, actor, inventor and engineer. He is best remembered today for his novels. Those published under the pseudonym Vernon Sullivan were bizarre parodies of criminal fiction, highly controversial at the time of their release. Vian's other fiction, published under his real name, featured a highly individual writing style with numerous made-up words, subtle wordplay and surrealistic plots. His novel L'Écume des jours (literally: "The Foam of Days") is the best known of these works and one of the few translated into English, under the title of Froth on the Daydream.

Vian was also an important influence on the French jazz scene. He served as liaison for Hoagy Carmichael, Duke Ellington and Miles Davis in Paris, wrote for several French jazz-reviews (Le Jazz Hot, Paris Jazz) and published numerous articles dealing with jazz both in the United States and in France. His own music and songs enjoyed popularity during his lifetime, particularly the anti-war song "Le Déserteur" (The Deserter).

Biography

Early life

Vian was born in 1920 into an upper middle-class family in the wealthy Parisian suburb of Ville d'Avray (Hauts-de-Seine). His parents were Paul Vian, a young rentier, and Yvonne Ravenez, amateur pianist and harpist. From his father Vian inherited a distrust of the church and the military, as well as a love of the bohemian life. Vian was the second of four children: the others were Lélio (1918–1984), Alain (1921–1995) and Ninon (1924–2003). The family occupied the Les Fauvettes villa. The name "Boris" was chosen by Yvonne, an avid classical music lover, after seeing a performance of Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov.[1]

Vian suffered from ill health throughout his childhood and had to be educated at home until the age of five. From 1926 to 1932 he studied first at a small lycée, then at Lycée de Sèvres. After the Wall Street Crash of 1929 the family's financial situation worsened considerably and they moved to a small lodge near Les Fauvettes (from 1929 to 1932 the Vians rented the villa to Yehudi Menuhin's family). Shortly after Vian's 12th birthday he developed rheumatic fever and after a while he also contracted typhoid. [citation needed]

This combination led to severe health problems and left Vian with a heart condition that would ultimately lead to an early death. Vian gave an eyeblink to this heart condition in L'Écume des Jours, his most popular novel, featuring Chloë, the main female character as dying from a waterlily growing in her lung. [citation needed]

Formal education and teenage years

From 1932 to 1937, Vian studied at Lycée Hoche in Versailles. In 1936, Vian and his two brothers started organizing what they called "surprise-parties" (surprise parties). They partook of mescaline in the form of a Mexican cacti called peyote. These gatherings became the basis of his early novels: Trouble dans les andains (Turmoil in the Swaths) (1943) and particularly Vercoquin et le plancton (Vercoquin and the Plankton) (1943–44). It was also in 1936 that Vian got interested in jazz; the next year he started playing the trumpet and joined the Hot Club de France.

In 1937, Vian graduated from Lycée Hoche, passing baccalauréats in mathematics, philosophy, Latin, Greek and German. He subsequently enrolled at Lycée Condorcet, Paris, where he studied special mathematics until 1939. Vian became fully immersed in the French jazz scene: for example, in 1939 he helped organize Duke Ellington's second concert in France. When WWII started, Vian was not accepted into the army due to poor health. He entered École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures in Paris and subsequently moved to Angoulême when the school moved there because of the war.

In 1940, Vian met Michelle Léglise, who became his wife in 1941. She taught Vian English and introduced him to translations of American literature. Also in 1940, Vian met Jacques Loustalot, who became a recurring character in several early novels and short stories as "the colonel". Loustalot died accidentally in 1949 falling from a building he was trying to climb on in order to enter into a flat by the window, after a bet. In 1942, Vian and his brothers joined a jazz orchestra under the direction of Claude Abbadie, who became a minor character in Vian's Vercoquin et le plancton. The same year, Vian graduated from École Centrale with a diploma in metallurgy, and his son Patrick was born.

Career

After Vian's graduation, he and Michelle moved to Paris' 10th arrondissement and, on 24 August 1942 he became an engineer at the French Association for Standardisation (AFNOR). By this time he was an accomplished jazz trumpeter, and in 1943 he wrote his first novel, Trouble dans les andains (Turmoil in the Swaths). His literary career started in 1943 with his first publication, a poem, in the Hot Club de France bulletin. The poem was signed Bison Ravi ("Delighted Bison"), an anagram of Vian's real name. The same year Vian's father died, murdered at home by burglars.

In 1944 Vian completed Vercoquin et le plancton (Vercoquin and the Plankton), a novel inspired partly by surprise-parties of his youth and partly by his job at the AFNOR (which is heavily satirized in the novel). Raymond Queneau and Jean Rostand helped Vian to publish this work at Éditions Gallimard in 1947, along with several works Vian completed in 1946. These included his first major novels, L'Écume des jours and L'automne à Pékin (Autumn in Peking). The former, a tragic love story in which real world objects respond to the characters' emotions, is now regarded as Vian's masterpiece, but at the time of its publication it failed to attract any considerable attention. L'automne à Pékin, which also had a love story at its heart but was somewhat more complex, also failed to sell well.

Frustrated by the commercial failure of his works, Vian vowed he could write a best-seller and wrote the hard-boiled novel I Spit on Your Graves (J'irai cracher sur vos tombes) in only 15 days. Vian wrote an introduction in which he claimed to be the translator of the American shooting star writer by the name Vernon Sullivan. Vian persuaded his friend Jean d'Halluin, a début publisher, to publish the novel in 1947. Eventually the hoax became known and the book became one of the best-selling titles of that year. Vian wrote three more Vernon Sullivan novels from 1947 to 1949.

The year 1946 marked a turning point in Vian's life: At one of the popular parties that he and Michelle hosted he made the acquaintance of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Albert Camus, became a regular in their literary circles and started regularly publishing various materials in Les Temps Modernes. Vian admired Sartre in particular and gave him a prominent role—as "Jean-Sol Partre"—in L'Écume des jours (litt. "The foam of the days") published in English under the title: Froth on the Daydream. Ironically, Sartre and Michelle Vian commenced a relationship that would eventually destroy Vian's marriage.

Despite his literary work becoming more important, Vian never left the jazz scene. He became a regular contributor to various jazz-related magazines, and played trumpet at Le Tabou. As a result, his financial situation improved, and he abandoned the job at the AFNOR. Vian also formed his own choir, La petite chorale de Saint-Germain-des-Pieds [sic].[2]

Later years

The year 1948 saw the birth of Vian's daughter, Carole. He continued his literary career by writing Vernon Sullivan novels, and also published poetry collections: Barnum's Digest (1948) and Cantilènes en gelée (Cantelinas in Jelly) (1949). Vian also started writing plays, the first of which, L'Équarrissage pour tous (Slaughter for Everyone), was staged the year it was written, 1950. The same year saw publication of Vian's third major novel, L'Herbe rouge (The Red Grass). This was a much darker story than its predecessors, centering on a man who built a giant machine that could help him psychoanalyse his soul. Like the other two books, it did not sell well; Vian's financial situation had been steadily worsening since late 1948, and he was forced to take up translation of English-language literature and articles to get by. Vian separated from his wife, and in 1950 he met Ursula Kübler (1928–2010), a Swiss dancer; the two started an affair, and in 1951 Vian divorced Michelle. Ursula and Boris married in 1954.

Vian's last novel, L'Arrache-cœur (The Heart-extractor), was published in 1953, yet again to poor sales and Vian effectively stopped writing fiction. The only work that appeared after 1953 was a revised version of L'automne à Pékin, published 1956. He concentrated on a new field, song-writing and performing, and continued writing poetry. Vian's songs were successful; in 1954 he embarked on his first tour as singer-songwriter. By 1955, when he was working as art director for Philips, Vian was active in a wide variety of fields: song-writing, opera, screenplays and several more plays. His first album, Chansons possibles et impossibles (Possible and Impossible Songs), was also recorded in 1955. He wrote the first French rock and roll songs with his friend Henri Salvador, who sang them under the nickname Henry Cording. He also wrote "Java Pour Petula" (a song about an English girl arriving in France, written in Parisian argot) for Petula Clark's first concert performances in France.

Still in 1955, Vian decided to perform some of his songs on stage himself. He had been a little upset that French singer Marcel Mouloudji (1922-1994), who had interpreted "Le Deserteur" (The Deserter) on stage the year before, had not accepted the original lyrics because he thought that they would lead to the song being banned. Although Vian accepted a change to one verse, the song was banned from TV and radio channels until 1967. The record of Vian's songs performed by himself was not successful in France until ten years after his death.

Vian's life was endangered in 1956 by a pulmonary edema, but he survived and continued working with the same intensity as before. In 1957, Vian completed another play: Les Bâtisseurs d'empire (The Empire Builders), which was only published and staged in 1959. In 1958, Vian worked on the opera Fiesta with Darius Milhaud, and a collection of his essays, En avant la zizique... Et par ici les gros sous (On with the Muzak... And Bring in the Big Bucks), was published the same year.

Death

On the morning of 23 June 1959, Vian was at the Cinema Marbeuf for the screening of the film version of I will Spit on Your Graves. He had already fought with the producers over their interpretation of his work, and he publicly denounced the film, stating that he wished to have his name removed from the credits. A few minutes after the film began, he reportedly blurted out: "These guys are supposed to be American? My ass!" He then collapsed into his seat and died from sudden cardiac death en route to the hospital.[3]

Legacy

During his lifetime, only the novels published under the name of Vernon Sullivan were successful. Those published under his real name, which had real literary value in his eyes, remained a commercial failure, despite the support of famous authors of this time.[4]

But, almost immediately after his death, L'Écume des jours, then L'automne à Pékin, L'Arrache-coeur, and L'Herbe rouge, started to get recognition in France. They finally made Boris Vian into a legend for the youth of the 1960s and 1970s.[5]

Writing songs for artists of his time[6] allowed Vian in 1954 to get out of the problems he had with the IRS by confessing, after the amnesty of 1947, he was the author of I shall spit on your graves (considered pornographic, which had incurred the wrath of justice in 1946, and was banned again in 1949, along with his play L'Équarrissage pour tous in 1950).[7][8] However, when he decided to sing himself the songs which were rejected by the stars, he succeeded only in reaching a limited audience (among which Léo Ferré et Georges Brassens), the public remaining unconvinced by his talent for singing.[9] Nevertheless the May 1968 in France generation, even more than the previous ones, loved his songs too, especially because of their impertinence.

As a songwriter, Vian also inspired Serge Gainsbourg, who used to attend his show at the cabaret Les Trois Baudets and who wrote, thirty years later: "I took it on the chin [...], he sang terrific things [...], it is because I heard him that I decided to try something interesting".[10] As a critic, Boris Vian was the first to support Gainsbourg in Le Canard Enchaîné, in 1957.

Over the years, Vian's work have become classics, often celebrated and selected as subjects of study in schools.[11] To this day, Vian is still viewed as the emblematic figure of Saint Germain des Prés as it existed during the postwar decade, when this district was the centre of artistic and intellectual life in Paris; even more so than Jean-Paul Sartre and Juliette Greco, despite the fact that, contrary to legend, Vian did not create this movement.[12][13]

Selected bibliography

Prose

Novels

- Trouble dans les andains (Turmoil in the Swaths) (1942–43, published posthumously in 1966 by La Jeune Parque)

- Vercoquin et le plancton (Vercoquin and the Plankton) (1943–45, published 1947 by Éditions Gallimard)

- L'Écume des jours (Foam of the Days) (1946, published 1947 by Éditions Gallimard; translated variously as Froth on the Daydream, Mood Indigo and Foam of the Daze)

- L'automne à Pékin (Autumn in Peking) (1946, published 1947 by Éditions du Scorpion, revised version published in 1956; Autumn in Peking)

- L'Herbe rouge (The Red Grass) (1948–49, published 1950 by Éditions Toutain)

- L'Arrache-coeur (Heartsnatcher) (1947–1951, published 1953 by Éditions Vrille; Heartsnatcher)

Vernon Sullivan novels

- J'irai cracher sur vos tombes (I Shall Spit on Your Graves[14]) (Éditions du Scorpion, 1946)

- Les morts ont tous la même peau (The Dead All Have the Same Skin) (Éditions du Scorpion, 1947)

- Et on tuera tous les affreux (To Hell With the Ugly) (Éditions du Scorpion, 1948)

- Elles se rendent pas compte (They Do Not Realize) (1948–50, published 1950 by Éditions du Scorpion)

Short story collections

- Les Fourmis (The Ants) (1944–47, published 1949 by Éditions du Scorpion)

- Les Lurettes fourrées (Ages Fulfilled) (1948–49, published 1950 by Le Livre de Poche as an addendum to their edition of L'Herbe rouge)

- Le Ratichon baigneur (Toothy Bather) (1946–52, published posthumously in 1981 by Éditions Bourgois)

- Le Loup-garou (The Werewolf) (1945–53?, published posthumously in 1970 by Éditions Bourgois)

Dramatic works

- L'Équarrissage pour tous (Squaring for All), play (1947, published 1950 by Éditions Toutain)

- Le Dernier des métiers (The Last of the Trades), play (1950, published 1965 by Éditions Pauvert)

- Tête de Méduse (Medusa's Head), comedy in one act (1951, published 1971 by U.G.E.)

- Série Blême (Pallid Series), tragedy in three acts (1952?, published 1971 by U.G.E.)

- Le Chasseur français (The French Hunter), vaudeville (1955, published 1971 by U.G.E.)

- Les Bâtisseurs d'Empire (The Empire Builders), (1957, published 1959 by Collège de 'Pataphysique)

- Le Goûter des généraux (The Snack of Generals), (1951, published 1962 by Collège de 'Pataphysique)

Poetry

- Barnum's Digest (Barnum's Digest) (1948, a collection of 10 poems)

- Cantilènes en gelée (Cantelinas in Jelly) (1949)

- Je voudrais pas crever ((I'd prefer not to die)) (posthumously published in 1962)

Translations

- The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler as Le grand sommeil (1948)

- The Lady in the Lake by Raymond Chandler as La dame du lac (1948)

- The World of Null-A by A. E. van Vogt, as Le Monde des Å (1958)

Other works

- Manuel de St-Germain-des-Prés, originally commissioned to be a tourist guide to the St-Germain-des-Prés district (published 1950 by Éditions Toutain)

See also

- Boris Vian Template:Fr icon

- The Vian family Template:Fr icon

- Existentialism

- Pataphysics

- Zazou

- Amour de poche (1957)

Video

Notes

- ^ Boris Vian: La schiuma dei giorni. marcosymarcos.com. Retrieved 18 August 2014. Template:It icon

- ^ La petite chorale de Saint-Germain-des-Pieds

- ^ Boggio p. 461

- ^ Richaud p. 151

- ^ Dictionnaire des auteurs p. 606

- ^ Boggio p. 405, 409

- ^ Boggio p. 202

- ^ Richaud p. 75, 97

- ^ Boggio p. 414, 437

- ^ L'Arc Journal (#90) special issue devoted to Boris Vian, 1984

- ^ http://clg-boris-vian.scola.ac-paris.fr

- ^ Richaud p. 78, 80

- ^ Boggio p. 175, 224

- ^ full title in the BNF exposition

References

- Biographie, in L'Arrache-cœur, LGF – Livre de Poche, 2006. ISBN 978-2-253-00662-6

- Geoffrey Dearson. Lexical Transfer in the novels of Boris Vian (Diss. University of Wales, UK), [1]

- Philippe Boggio, Boris Vian, Le Livre de Poche-Hachette, Paris, 1995, 476 p. ISBN 978-2-253-13871-6

- Frédéric Richaud, Boris Vian, c'est joli de vivre, éditions du Chêne, Paris, 1999, 174 p. ISBN 978-2-842-77177-5

- Dictionnaire des auteurs, vol. 4, t. IV, by Antoine Berman, Laffont-Bompiani edition, Paris, 1990, 756 p ISBN 2-221-50175-6

- Rolls, Alistair Charles (1999). The Flight of the Angels: Intertextuality in Four Novels of Boris Vian. Atlanta, Georgia: Editions Ropodi. ISBN 90-420-0467-3.

External links

- Boris Vian Official website borisvian.org. Retrieved 14 December 2007.Template:Fr icon

- Boris Vian page. tamtambooks.com. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- Boris Vian page. amazon.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- Le Déserteur. antiwarsongs.org. Retrieved 25 December 2004.

- Boris Vian at IMDb

- Use dmy dates from May 2011

- 1920 births

- 1959 deaths

- People from Ville-d'Avray

- École Centrale Paris alumni

- French male singers

- French-language singers

- Jazz writers

- Pataphysicians

- Lycée Condorcet alumni

- Lycée Hoche alumni

- 20th-century French poets

- 20th-century French dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century French singers

- French male poets