Bowral

| Bowral New South Wales | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

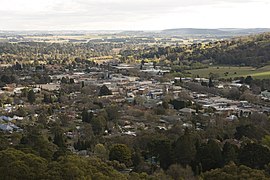

Aerial view of Bowral | |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 34°28′45″S 150°25′5″E / 34.47917°S 150.41806°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 10,764 (SAL 2021)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1861 | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 2576 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 690 m (2,264 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Location |

| ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | Wingecarribee Shire | ||||||||||||||

| Region | Southern Highlands | ||||||||||||||

| County | Camden | ||||||||||||||

| Parish | Mittagong | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Wollondilly | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Whitlam | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Bowral (/ˈbaʊrəl/)[2] is the largest town in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, Australia, about ninety minutes southwest of Sydney. It is the main business and entertainment precinct of the Wingecarribee Shire and Highlands.

Bowral once served as a rural summer retreat for the gentry of Sydney, resulting in the establishment of a number of estates and manor houses in the district. [3] Bowral is often associated with the cricketer Sir Donald Bradman.

Bowral is close to several other historic towns, being 5 kilometres (3 mi) from Mittagong, 9 kilometres (6 mi) from both Moss Vale and Berrima. The suburb of East Bowral and the village of Burradoo are nearby.

History

[edit]Bowral's colonial history extends back for approximately 200 years. During the pre-colonial era, the land was home to an Aboriginal tribe known as Tharawal (or Dharawal). The first European arrival was ex-convict John Wilson, who was commissioned by Governor Hunter to explore south of the new colony of Sydney. Other people to traverse the area include John Warby and botanist George Caley (an associate of Joseph Banks), the Hume brothers and later famous pioneer explorers John Oxley and Charles Throsby. Governor Lachlan Macquarie of the New South Wales colony had appointed 2,400 acres (9.7 km2) to John Oxley in a land grant, which was later incorporated as Bowral.

The town grew rapidly between the 1860s and the 1890s, mainly due to the building of the railway line from Sydney to Melbourne. In 1863, a permanent stone building was built for the church. However, the building would be replaced by the first Anglican church of St Simon and St Jude. The church was designed by Edmund Blacket and was built on the glebe in 1874. The church was expanded in 1887 to cater for a growing number of worshippers. Today, only Blackett's belltower remains.[4] One of the earliest houses built as a mountain retreat was Craigieburn which was constructed in 1885.

Gardens and European plants flourished from 1887, when citizens of Bowral started planting deciduous trees to make the area look more reminiscent of Europe and the British. This legacy still lives on throughout Bowral. Notably, the oaks at the start of Bong Bong St are a characteristic that makes Bowral distinct from other rural towns, giving it strong autumn colour. The town became somewhat affluent, as many wealthy Sydney-siders purchased property or land in the town and built grand Victorian weatherboard homes.

Heritage listings

[edit]

Bowral has a number of heritage-listed sites, including:

- Evans Lane: Kurkulla[5]

- Glebe Street: Bradman Oval[6]

- Oxley Drive: Mount Gibraltar Trachyte Quarries Complex[7]

Etymology

[edit]Bowral, and the former spelling Bowrall,[8] may have been derived from an Dharawal word bowrel meaning "high".[9]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 2,620 | — |

| 1933 | 3,005 | +14.7% |

| 1947 | 3,660 | +21.8% |

| 1954 | 3,926 | +7.3% |

| 1961 | 4,922 | +25.4% |

| 1966 | 5,210 | +5.9% |

| 1971 | 5,903 | +13.3% |

| 1976 | 6,283 | +6.4% |

| 1981 | 6,862 | +9.2% |

| 1986 | 7,390 | +7.7% |

| 1991 | 7,929 | +7.3% |

| 1996 | 8,705 | +9.8% |

| 2001 | 10,325 | +18.6% |

| 2006 | 6,971 | −32.5% |

| 2011 | 8,022 | +15.1% |

| 2016 | 10,335 | +28.8% |

| 2021 | 10,764 | +4.2% |

| Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics data.[10][11] Note: after 2001, Bowral and Mittagong became merged as a single urban locality for statistical purposes, and the population above counts Bowral as a State suburb instead. | ||

The 2021 census recorded Bowral's population as 10,764.[12]

At the 2016 census, Bowral area, including Burradoo, had a population of 12,949.[13] A more local area had a population of 10,335.[14]

In 2021, 73.5% of people in Bowral were born in Australia. The next most common countries of birth were England 7.1% and New Zealand 1.8%. 88.0% of people spoke only English at home. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people made up 1.0% of Bowral's population. The most common responses for religion in Bowral were No Religion 33.0%, Anglican 22.0%, and Catholic 21.2%.[13]

In the 21st century, Bowral has become a haven for retirees and empty nesters, commonly from Sydney: 13.3% of Bowral's population is aged 55–64 years (compared with the national average of 11.8%) and 35.5% is aged over 64 years (compared with the national average of 15.8%).[13] Consequently, the town has a number of retirement villages,[15] some located only minutes' walk from the central business district and hospitals. Also, as measured during the 2021 census, 36.3% of the town's population are under the age of 45, whereas for the nation the figure is 58.1%.[13]

Transportation

[edit]

Bowral is about 5 kilometres (3 mi) from the Hume Highway, which goes north to Sydney and south to Canberra, the Snowy Mountains and Melbourne. In the past, Bowral served as an overnight stop-over for travellers.

Bowral railway station is served by the Southern Highlands Line with services between Sydney and Moss Vale or Goulburn. Long distance services operate to Canberra and Griffith.

It has public bus routes to Nowra, Albion Park and Wollongong. A private operator provides a service six days a week from Bowral to Greater Sydney (Campbelltown, Liverpool and Parramatta) and to the Shoalhaven and south coast of New South Wales.

Climate

[edit]Bowral has an oceanic climate (Cfb), enjoying warm to mild, rainy summers and quite cool to cold winters with modest sunshine. Frost is common during winter and can even occur in summer. Snowfalls are rare, although falls in excess of 15 cm have been recorded. Historically maximum and minimum have ranged from 40.0 °C (104.0 °F) on 30 January 2003 to −11.2 °C (11.8 °F) on 11 July 1971.

| Climate data for Bowral (Parry Drive, 1961–2015); 690 m AMSL; 34.49° S, 150.40° E | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 40.0 (104.0) |

39.1 (102.4) |

35.7 (96.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

25.5 (77.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

29.1 (84.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

38.3 (100.9) |

37.2 (99.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 25.5 (77.9) |

24.4 (75.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.3 (66.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

18.7 (65.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.3 (41.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.6 (52.9) |

7.9 (46.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 81.9 (3.22) |

98.4 (3.87) |

95.2 (3.75) |

75.8 (2.98) |

69.6 (2.74) |

84.0 (3.31) |

45.3 (1.78) |

61.6 (2.43) |

55.8 (2.20) |

71.6 (2.82) |

92.4 (3.64) |

78.6 (3.09) |

931.7 (36.68) |

| Average precipitation days | 13.5 | 13.4 | 13.3 | 11.1 | 11.2 | 11.2 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 11.6 | 13.5 | 12.6 | 141.1 |

| Average afternoon relative humidity (%) | 57 | 64 | 61 | 61 | 65 | 67 | 64 | 56 | 54 | 56 | 60 | 56 | 60 |

| Source: [16] | |||||||||||||

Tourist attractions

[edit]

Bowral is noted for its boutiques, antique stores, gourmet restaurants and cafés.

The Bradman Oval, Bradman Museum and International Cricket Hall of Fame are dedicated to the achievements of cricketer Sir Donald Bradman and to the game of cricket.[17]

Cecil Hoskins Nature Reserve, in the suburb's south, is a large picnic area known for its birdwatching.

Bowral is the setting for Tulip Time at the Corbett Gardens,[18] a springtime celebration with a profusion of tulips and other flowers planted in the town centre.[19] A comprehensive private not-for-profit botanic garden includes a mix of exotic, native, and endemic species including a shale woodland, the endangered ecological community endemic to the site.[20]

The town has a Vietnam War Memorial and Cherry Tree Walk, constructed along the Mittagong Rivulet that flows through the town. Along a walking/cycle track beside the stream are planted 526 cherry trees, each dedicated to a soldier who died in the service of his country.[21]

Bowral and surrounding region was proclaimed a book town in 2000,[22] having numerous bookshops and associations with many literary figures including P. L. Travers, the author of the Mary Poppins novels,[23] Arthur Upfield, and many others.[24]

First held in 2016, each spring, Bowral hosts a popular cycling event: "The Bowral Classic", which draws hundreds of participants to compete.[25][26] There are multiple races ranging from 35 km to 160 km.

The Bong Bong Picnic Races, commenced in 1886, attracted crowds of up to 35,000 but were suspended in 1985 and resumed in 1992 as a members-only event. The event attracts around 5,000 people and is held annually in November,[27] as well as other events during the year.

Bowral is also home to a few vineyards and cellar doors and is close to Mittagong, the winery centre of the Southern Highlands. There are 60 vineyards in the Southern Highlands, which is a recognised cool-climate wine district. Wineries around Bowral are listed in the Southern Highlands Wineries Index.[28]

Bowral is overshadowed by Mount Gibraltar, which rises to 863 metres (2,831 ft) above sea level and has lookouts over Bowral, Mittagong, Moss Vale and the ranges near Bundanoon.

Hospitals

[edit]The town is served by the Bowral and District Hospital, which also serves the Southern Highlands region.[29] Founded in 1889, it is the only hospital operated outside the Sydney metropolitan area by the South Western Sydney Local Health District.

Bowral also has access to a private hospital operated by Ramsay Health Care, which includes short and long stay facilities although it lacks an emergency department.[30]

Schools

[edit]Schools in Bowral:

- Bowral High School

- Bowral Public School

- Chevalier College (Burradoo)

- Oxley College (Burradoo)

- Southern Highlands Christian School (East Bowral)

- St Thomas Aquinas Catholic Primary School

Churches

[edit]Churches in Bowral:

- The Fields Church, an Acts 29 Network church

- St Simon's and St Jude's Anglican Church

- St Thomas Aquinas Roman Catholic Church

- St Andrew's Presbyterian Church

- Bowral Uniting Church

- Bowral First Church of Christ, Scientist

- Bowral Baptist Church

- Bowral Salvation Army

- Bowral Church of Christ

- Seventh-day Adventist Church

Media

[edit]Television

[edit]Bowral receive five free-to-air television stations (television in Australia) including two government funded networks:

The ABC, the SBS and three commercial networks:

ABC, SBS, Seven, Nine (WIN) and Southern Cross 10 all offer digital high-definition simulcasts of their main channels.

All five networks broadcast additional channels including: 7two, 7mate, 7flix, 9Go!, 9Gem, 9Life, ABC TV Plus, ABC ME, ABC News, SBS Viceland, SBS World Movies, SBS Food, 10 Bold, 10 Peach and 10 Shake.

Radio

[edit]Radio stations that broadcast to the town are:

- Highland FM (107.1 FM community) [31]

- VOX FM (106.9 FM community)

- Wave FM (96.5 FM commercial)

- ABC Illawarra (97.3 FM ABC Local Radio that broadcast to the town)

- Triple J (98.9 FM),

- Radio National (1431 AM),

- ABC Classic FM (95.7 FM)

- Newsradio (90.9 FM)

Newspapers

[edit]The Southern Highland News is the town's local weekly newspaper. [32]

Notable residents

[edit]- Sir Edmund Barton: First Prime Minister of Australia

- Billy Birmingham: comedian, aka "The 12th Man"

- Sir Donald Bradman: Australian cricketer, the town's welcoming sign features a likeness of him getting ready to hit.[33]

- Ita Buttrose: journalist, businesswoman, and Australian of the year 2013

- Jennifer Byrne: journalist and former book publisher

- Richard Carleton: former 60 Minutes reporter. Born in Bowral

- Lauren Cheatle: Lives in Bowral. Fast Bowler for Australia women's cricket team, NSW Breakers and Sydney Sixers.

- Bryce Courtenay: South African novelist

- G. F. J. Dart: headmaster of Ballarat Grammar School 1942–1970

- Andrew Denton: television producer, comedian, television presenter and former radio host

- Frank Debenham: Antarctic scientist and geographer

- Roy De Maistre: painter, born Bowral 1894

- Lorrae Desmond: actress (A Country Practice). Born in Mittagong

- John Fahey: former NSW Premier, federal parliamentarian, president of the (sports) World Anti-Doping Agency

- Peter Garrett: former Gillard government minister and band member of Midnight Oil

- Scott Geddes: rugby league player

- Merv Hicks: Rugby league international

- Nathan Hindmarsh: Parramatta Eels captain NRL

- Geoff Jansz: television chef

- James Kemsley: cartoonist (Ginger Meggs)

- Graham Kennedy: "The King" of Australian television

- John Kerin: politician, former Treasurer of Australia. Born in Bowral

- Peter Khan: former member of the Universal House of Justice, the supreme governing institution of the Baháʼí Faith[34][circular reference].

- Elspeth McLachlan: neuroscientist, born in Bowral

- Geoff Morrell: artist, actor Blue Heelers

- John Olsen: artist

- Paul Ramsay: businessman and philanthropist

- Craig Reucassel: television satirist, attended Bowral High School

- Leo Sayer: singer-songwriter

- Clement Semmler: author, reviewer and deputy general manager of the ABC

- Tim Storrier: artist, winner of the 2012 Archibald Prize

- P. L. Travers: author of Mary Poppins

- Arthur Upfield: author of the Boney detective novels

- Paul White: "The Jungle Doctor" medical missionary to Tanganyika, author

- Geordie Williamson: Mathematician specialising in representation theory

- Tim the Yowie Man, lived his formative years in Bowral from 1982 to 1990. Cryptonaturalist, author, tour guide, motivational speaker, tv personality, radio broadcaster.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Bowral (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ Macquarie Dictionary, Fourth Edition (2005). Melbourne, The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd. ISBN 1-876429-14-3

- ^ Wilson, Robert (1990). Discover Australia. Books for Pleasure. ISBN 978-1863021142.

- ^ "St Jude's: History and Heritage". Archived from the original on 8 March 2014.

- ^ "Kurkulla". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00503. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Bradman Oval and Collection of Cricket Memorabilia". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01399. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "Mount Gibraltar Trachyte Quarries Complex". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01917. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC BY 4.0 licence.

- ^ "okTravel – Bowral Profile". Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ Croucher, John S. (2020). A Concise History of New South Wales. Woodslane Press. ISBN 978-1-92-586839-5.

Its name is thought to derive from the Dharawal word 'bowrel', meaning 'high'.

- ^ "Statistics by Catalogue Number". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ "Search Census data". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ "2021 Bowral, Census All persons QuickStats". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d "2021 Bowral, Census All persons QuickStats | Australian Bureau of Statistics". www.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Bowral (state suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ Retirement villages in Bowral Archived 8 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine at Villages.com.au directory

- ^ "Climate statistics for Bowral (Parry Drive)". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "Home | Bradman Foundation". www.bradman.com.au. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Tulip Time Archived 23 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine at southern-highlands.com.au

- ^ Gardens Archived 26 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine at southern-highlands.com.au

- ^ Southern Highlands Botanic Gardens Archived 9 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 5 September 2013

- ^ Cherry Tree Walk Vietnam War Memorial at Vietnam Veterans Association of Australia website

- ^ Australasia's First Book Town launched in NSW Southern Highlands March 2000. Archived 14 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine Media release at Booktown Australia

- ^ "Mary Poppins Birthplace - Bowral". Mary Poppins Birthplace - Bowral.

- ^ BOOKtrail Launched in NSW Southern Highlands Archived 14 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine Media release at Booktown Australia

- ^ "Bowral Classic - NSW road cycling event 18 October 2020". Bowral Classic. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Bowral Classic". www.visitnsw.com. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Bong Bong Picnic Race Club Limited". www.bongbongprc.com.au.

- ^ Southern Highlands Wineries Index at highlandsnsw.com.au

- ^ "Bowral Hospital". Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ "Contact Us". www.southernhighlandsprivate.com.au. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Highland FM". Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ "Southern Highland News". Retrieved 22 November 2024.

- ^ "Videos | cricket.com.au". www.cricket.com.au. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ Peter Khan

External links

[edit]- Wingecaribee Shire Council – Administering and Based in Moss Vale

- Information on Bowral and its History Archived 21 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- BookTown Australia Archived 18 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Southern Highlands News". (local newspaper). Archived from the original on 21 May 2008.