Claude Johnson

Claude Goodman Johnson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 24 October 1864 |

| Died | 12 April 1926 (aged 61) London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Founding managing director of Rolls-Royce |

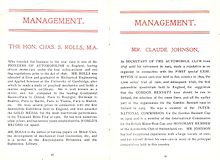

Claude Goodman Johnson (24 October 1864 – 12 April 1926) was a British motor vehicle manufacturer who was instrumental in the creation of Rolls-Royce Limited.

Johnson described himself as the hyphen in the Rolls-Royce name.[1] When Royce fell ill and took his design staff home in 1908, and after the death of Rolls in July 1910, it was Johnson who was responsible for keeping the business running, until his own death in April 1926.[2]

Early life

Claude Johnson was born in Datchet, Berkshire on 24 October 1864 to the middle of the large family of William Goodman Johnson and his wife Sophia Fanny (née Adams).[3][4] His father was on the staff of the South Kensington Museum.[4]

Known as CJ, Johnson was a large broad-shouldered extrovert.[2]

RAC

Educated at St Paul's School he briefly attended the Art School, South Kensington, joined the Imperial Institute in South Kensington and, for the institute, organised the first automobile exhibition in England at Richmond Park in 1896.[5] Hired in 1897 by F R Simms, who had noted his organisational ability and public relations flair, Johnson became the first secretary of the Royal Automobile Club (RAC) where he organised the club's Thousand Mile trial of 1900. The RAC Club's Jubilee Book simply stated "To him is owed the fact of the club's existence today".[2]

Leaving the RAC in 1903 originally for a manufacturing venture Johnson became joint manager with Charles Rolls of C.S. Rolls & Co finding high quality cars for friends which was to lead first to their discovery of F H Royce in Manchester and a 1904 contract for Royce to supply cars branded Rolls-Royce and then in 1906 to Rolls-Royce Limited.[6]

Johnson became a close friend with newspaper proprietor Alfred Harmsworth which ensured more publicity, Harmsworth personally dominated the British press.[2]

Rolls-Royce

Scottish Reliability Trial 22 June 1907

green leather, silver-plated fittings, aluminium dashboard, an opulent display

At first responsibilities were divided three ways. Charles Rolls promoted the cars by competing in trials and races, Johnson understudied Rolls at this but was also responsible for sales as well as business organisation,[7] Royce's responsibility was production.[2]

Claude Johnson brought the necessary business acumen to the partnership of Rolls and Royce. The board soon recognised that Royce was a poor production engineer but a brilliant designer. In 1908 after four years of incessant work Royce's health failed. Johnson persuaded the increasingly temperamental Royce to work at home with a team of draughtsmen.[2]

Rolls's death in 1910 triggered a breakdown in Royce's health and he underwent a major operation. Johnson persuaded him to live in a villa in the south of France—next to Johnson's own villa— with his drawing office and personal staff of eight in adjoining premises. Thereafter Royce divided his time between winters in France and Kent, later West Wittering in Sussex and "never came within a hundred miles of Derby".[2]

It was Johnson's idea to limit their various car models to one, the 40/50, smooth, silent, solid, costly—the best car that money can buy— and reliable as he rapidly demonstrated to the buying public. A journalist promptly dubbed it the best car in the world. The original car finished in special livery to Johnson’s special order and was named in advance by him as The Silver Ghost. It is pictured here in 1907 when new and again 97 years later on display at the celebration of the company's centenary in 2004. He drove his unique Silver Ghost non-stop around Britain for 15,000 miles and then asked the RAC to strip it down and restore its working parts to mint condition. Instead of the major overhaul any other car of the day would have required, the Silver Ghost's repair bill came to only £2.2s 7d. (£2.13)[8] The name "Silver Ghost" caught on and though never officially used is since used for all 7,874 of the 40/50 model which remained in production until his death in 1926.

For the Spirit of Ecstasy mascot he hired the sculptor Charles Sykes who used as his model the society belle Eleanor Thornton, secretary to John Scott Montagu, Lord Montagu of Beaulieu.[9]

Aero-engines

In the winter of 1915–1916 Johnson personally named the first three Rolls-Royce aircraft piston engines, the Eagle, Hawk and Falcon, starting the company's tradition of naming piston aero engines after birds of prey.[10]

By 1918 Johnson's business was the world's largest producer of aero-engines. Post-war the business prospered[2]

Tribute

Johnson died on 12 April 1926 aged 61 at his house in London, 3 Adelphi Terrace House, Robert St, now NW1. Though suffering from a cold he had insisted on attending a niece's wedding and succumbed to pneumonia.[6] Married twice, in 1891 and 1919, Johnson left a widow, Evelyn Maud who remarried and died in 1955, and two surviving children, a daughter from each marriage.

"Since we last met the company has suffered a grievous loss by the death of Mr Claude Johnson to whose policy, coupled with the engineering achievements of Mr Royce, it owes its present pre-eminence. A memorial to him designed by Sir Herbert Baker and with an inscription written by Mr Rudyard Kipling is to be erected at the works. Mr Basil Johnson, who has been appointed the new managing director, was previously the general manager, and for 12 years shared with his brother the management of the company's affairs." Lord Wargrave, chairman[11]

"Our existing aero engines continue to maintain their reputation for unparalleled reliability. Quite recently three flying boats equipped with Rolls-Royce Eagle engines accomplished a memorable flight of 4,500 miles across Africa. Another flying boat, fitted with two Rolls-Royce Condor engines, succeeded in carrying 55 passengers at one time in its trials on Lake Constance. Such an achievement was as unique today as was the conquest of the Atlantic made by our engines in 1919. The first flights across the North and South Atlantic and to Australia, South Africa and India were all made by Rolls-Royce engines." Lord Wargrave, chairman.[11]

Publication

Johnson wrote The Early History of Motoring published after his death in 1927 by E J Burrow, London. It has a preface by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu and contains a brief history of Rolls-Royce as an appendix. It is accessible on Google Books.

Notes

- ^ The Silver Ghost. Claude Johnson ordered this car with its Barker body painted silver specifically to publicize their new 40/50 hp model which ran "with extraordinary stealthiness". Its name "The Silver Ghost" was carried on a special repoussé plaque on its dashboard. After the arrival of the Phantom model in 1925 the 40/50 cars were known as Silver Ghosts to distinguish them but this car was the only car entitled to the name.

References

- ^ Pugh 2000, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Martin Adeney, Johnson, Claude Goodman (1864–1926), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ Gentleman's Magazine 1858 p.43

- ^ a b Census 1881

- ^ Pugh 2000, p. 27.

- ^ a b Mr. Claude Johnson.The Times Monday, 12 April 1926; pg. 16; Issue 44243.

- ^ David J. Jeremy, Rolls, Charles Stewart (1877–1910), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ New Scientist 10 May 1979 – Page 438

- ^ Lord Montagu and David Burgess-Wise Daimler Century ; Stephens 1995 ISBN 1-85260-494-8

- ^ Gunston 1989, p. 137.

- ^ a b Chairman's address at the Annual General Meeting of shareholders of Rolls-Royce Limited The Times Tuesday, 22 February 1927; pg. 23; Issue 44512.

Bibliography

- Botticelli, Peter. Rolls-Royce and the Rise of High-Technology Industry. Thomas K McCraw (ed) Creating Modern Capitalism, Harvard College, 1997. ISBN 0-674-17555-7

- Gunston, Bill. World Encyclopaedia of Aero Engines. Cambridge, England. Patrick Stephens Limited, 1989. ISBN 1-85260-163-9

- Pugh, Peter. The Magic of a Name – The Rolls-Royce Story – The First 40 Years. Cambridge, England. Icon Books Ltd, 2000. ISBN 1-84046-151-9

- Oldham, W.J. The hyphen in Rolls-Royce: A biography of Claude Johnson. Written for them by a friend of his daughters this is a report of social events with little reference to business activities.