Corinthian War

| Corinthian War (395–387 BC) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spartan hegemony | |||||||||

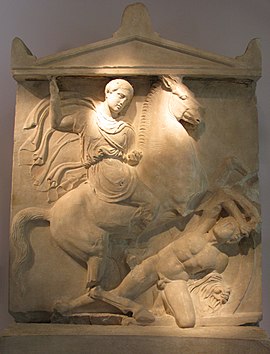

Athenian cavalryman Dexileos fighting a Peloponnesian hoplite in heroic nudity, in the Corinthian War.[1] Dexileos was killed in action near Corinth in the summer of 394 BC, probably in the Battle of Nemea,[1] or in a proximate engagement.[2] Grave Stele of Dexileos, 394–393 BC. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

The Corinthian War (395–387 BC) was a conflict in ancient Greece which pitted Sparta against a coalition of city-states comprising Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos, backed by the Achaemenid Empire. The war was caused by dissatisfaction with Spartan imperialism in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), both from Athens, the defeated side in that conflict, and from Sparta's former allies, Corinth and Thebes, who had not been properly rewarded. Taking advantage of the fact that the Spartan king Agesilaus II was away campaigning in Asia against the Achaemenid Empire, Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos forged an alliance in 395 BC with the goal of ending Spartan hegemony over Greece; the allies' war council was located in Corinth, which gave its name to the war. By the end of the conflict, the allies had failed to end Spartan hegemony over Greece, although Sparta was durably weakened by the war.

At first, the Spartans achieved several successes in pitched battles (at Nemea and Coroneia), but lost their advantage after their fleet was destroyed at the naval Battle of Cnidus against the Persian fleet, which effectively ended Sparta's attempts to become a naval power. As a result, Athens launched several naval campaigns in the later years of the war, recapturing a number of islands that had been part of the original Delian League during the 5th century BC. Alarmed by these Athenian successes, the Persians stopped backing the allies and began supporting Sparta. This defection forced the allies to seek peace.

The King's Peace, also known as the Peace of Antalcidas, was dictated by the Achaemenid King Artaxerxes II in 387 BC, ending the war. This treaty declared that Persia would control all of Ionia, and that all other Greek cities would be "autonomous", in effect prohibiting them from forming leagues, alliances or coalitions.[3] Sparta was to be the guardian of the peace, with the power to enforce its clauses. The effects of the war, therefore, were to establish Persia's ability to interfere successfully in Greek politics, to atomize and isolate from one another Greek city states, and to affirm Sparta's hegemonic position in the Greek political system.[4] Thebes was the main loser of the war, as the Boeotian League was disbanded and their cities were garrisoned by Sparta. Peace did not last long: war between Sparta and a resentful Thebes resumed in 378 BC, which finally led to the destruction of Spartan hegemony at the Battle of Leuctra in 371.

Events leading to the war

In the Peloponnesian War, which had ended in 404 BC, Sparta had enjoyed the support of nearly every mainland Greek state and the Persian Empire, and in the months and years following that war, a number of the island states of the Aegean had come under its control. This solid base of support, however, was fragmented in the years following the war. Despite the collaborative nature of the victory, Sparta alone received the plunder taken from the defeated states and the tribute payments from the former Athenian Empire.[5] Sparta's allies were further alienated when, in 402 BC, Sparta attacked and subdued Elis, a member of the Peloponnesian League that had angered the Spartans during the course of the Peloponnesian War. Corinth and Thebes refused to send troops to assist Sparta in its campaign against Elis.[6]

Thebes, Corinth and Athens also refused to participate in a Spartan expedition to Ionia in 398 BC, with the Thebans going so far as to disrupt a sacrifice that the Spartan king Agesilaus attempted to perform in their territory before his departure.[8] Despite the absence of these states, Agesilaus campaigned effectively against the Persians in Lydia, advancing as far inland as Sardis. The satrap Tissaphernes was executed for his failure to contain Agesilaus, and his replacement, Tithraustes, bribed the Spartans to move north, into the satrapy of Pharnabazus, Hellespontine Phrygia. Agesilaus did so, but simultaneously began preparing a sizable navy.[9]

Unable to defeat Agesilaus' army, Pharnabazus decided to force Agesilaus to withdraw by stirring up trouble on the Greek mainland. He dispatched Timocrates of Rhodes, an Asiatic Greek, to distribute ten thousand gold darics in the major cities of the mainland and incite them to act against Sparta.[10] Timocrates visited Athens, Thebes, Corinth, and Argos, and succeeded in persuading powerful factions in each of those states to pursue an anti-Spartan policy.[11] According to Plutarch, Agesilaus, the Spartan king, said upon leaving Asia "I have been driven out by 10,000 Persian archers", a reference to "Archers" (Toxotai) the Greek nickname for the Darics from their obverse design, because that much money had been paid to politicians in Athens and Thebes in order to start a war against Sparta.[12][7][13] The Thebans, who had previously demonstrated their antipathy towards Sparta, undertook to bring about a war.

Early events (395 BC)

Initial fighting: Battle of Haliartus (395 BC)

Xenophon claims that, unwilling to challenge Sparta directly, the Thebans instead choose to precipitate a war by encouraging their allies, the Locrians, to collect taxes from territory claimed by both Locris and Phocis. In response, the Phocians invaded Locris, and ransacked Locrian territory. The Locrians appealed to Thebes for assistance, and the Thebans invaded Phocian territory; the Phocians, in turn, appealed to their ally, Sparta, and the Spartans, pleased to have a pretext to discipline the Thebans, ordered general mobilization.[14] A Theban embassy was dispatched to Athens to request support; the Athenians voted to assist Thebes, and a perpetual alliance was concluded between Athens and the Boeotian confederacy.[15]

The Spartan plan called for two armies, one under Lysander and the other under Pausanias, to rendezvous at and attack the Boeotian city of Haliartus.[16] Lysander, arriving before Pausanias, successfully persuaded the city of Orchomenus to revolt from the Boeotian confederacy, and advanced to Haliartus with his troops and a force of Orchomenians. There, he was killed in the Battle of Haliartus after bringing his force too near the walls of the city; the battle ended inconclusively, with the Spartans suffering early losses but then defeating a group of Thebans who pursued the Spartans onto rough terrain where they were at a disadvantage. Pausanias, arriving a day later, took back the bodies of the Spartan dead under a truce, and returned to Sparta. There, he was put on trial for his life for failing to arrive and support Lysander at the designated time. He fled to Tegea before he could be convicted.[17]

Alliance against Sparta expands

In the wake of these events, both the Spartans and their opponents prepared for more serious fighting to come. In late 395 BC, Corinth and Argos entered the war as co-belligerents with Athens and Thebes. A council was formed at Corinth to manage the affairs of this alliance. The allies then sent emissaries to a number of smaller states and received the support of many of them.[18] Among the defections, there were: East Lokris, Thessaly, Leukas, Acarnania, Ambracia, Chalcidian Thrace, Euboea, Athamania, and Ainis. Meanwhile, the Boiotians and Argives captured Heraclea Trachinia. Only Phokis and Orchomenos remained loyal to Sparta in Central Greece.[19]

Alarmed by these developments, the Spartans prepared to send out an army against this new alliance, and sent a messenger to Agesilaus ordering him to return to Greece. The orders were a disappointment to Agesilaus, who had looked forward to further successful campaigning. It is said he wryly observed, but for ten thousand Persian "archers", he would have vanquished all Asia.[20] Thus, he turned back with his troops, crossing the Hellespont and marched west through Thrace.[21]

War on land and sea (394 BC)

Nemea

After a brief engagement between Thebes and Phocis, in which Thebes was victorious, the allies gathered a large army at Corinth. A sizable force was sent out from Sparta to challenge this force. The forces met at the dry bed of the Nemea River, in Corinthian territory, where the Spartans won a decisive victory. As often happened in hoplite battles, the right flank of each army was victorious, with the Spartans defeating the Athenians while the Thebans, Argives, and Corinthians defeated the various Peloponnesians opposite them; the Spartans then attacked and killed a number of Argives, Corinthians, and Thebans as these troops returned from pursuing the defeated Peloponnesians. The coalition army lost 2,800 men, while the Spartans and their allies lost only 1,100.[22]

Cnidus

The next major action of the war took place at sea, where both the Persians and the Spartans had assembled large fleets during Agesilaus's campaign in Asia. By levying ships from the Aegean states under his control, Agesilaus had raised a force of 120 triremes, which he placed under the command of his brother-in-law Peisander, who had never held a command of this nature before.[23] The Persians, meanwhile, had already assembled a joint Phoenician, Cilician, and Cypriot fleet, under the joint command of Achaemenid satrap Pharnabazus II and the experienced Athenian admiral Conon who was in self-exile and in the service of the Achaemenids after his infamous defeat at the Battle of Aegospotami. The fleet had already seized Rhodes from Spartan control in 396 BC.[citation needed]

These two fleets met off the point of Cnidus in 394 BC. The Spartans fought determinedly, particularly in the vicinity of Peisander's ship, but were eventually overwhelmed; large numbers of ships were sunk or captured, and the Spartan fleet was essentially wiped from the sea. Following this victory, Conon and Pharnabazus sailed along the coast of Ionia, expelling Spartan governors and garrisons from the cities of Kos, Nisyros, Telos, Chios, Mytilene, Ephesos, Erythrae, although they failed to reduce the Spartan bases at Abydos and Sestos under the command of Dercylidas, as well as the small bases of Aigai and Temnos.[24][25] Apart from Mytilene, Lesbos also remained pro-Spartan.[26] Based on numismatic evidence, the cities of Rhodes, Iasos, Knidos, Ephesos, Samos, Byzantium, Kyzikos, and Lampsakos, likely made an alliance against Sparta after the battle of Cnidus.[27]

Coronea

By this time, Agesilaus's army, after brushing off attacks from the Thessalians during its march through that country, had arrived in Boeotia, where it was met by an army gathered from the various states of the anti-Spartan alliance. Agesilaus's force from Asia, composed largely of emancipated helots and mercenary veterans of the Ten Thousand, was augmented by half a Spartan regiment from Orchomenus, and another half a regiment that had been transported across the Gulf of Corinth. These armies met each other at Coronea, in Theban territory; as at Nemea, both right wings were victorious, with the Thebans breaking through while the rest of the allies were defeated. Seeing that the rest of their force had been defeated, the Thebans formed up to break back through to their camp. Agesilaus met their force head on, and in the struggle that followed a number of Thebans were killed before the remainder were able to force their way through and rejoin their allies.[28] After this victory, Agesilaus sailed with his army across the Gulf of Corinth and returned to Sparta.

Later events (393–388 BC)

The events of 394 BC left the Spartans with the upper hand on land, but weak at sea. The coalition states had been unable to defeat the Spartan phalanx in the field, but had kept their alliance strong and prevented the Spartans from moving at will through central Greece. The Spartans would continue to attempt, over the next several years, to knock either Corinth or Argos out of the war; the anti-Spartan allies, meanwhile, sought to preserve their united front against Sparta, while Athens and Thebes took advantage of Sparta's preoccupation to enhance their own power in areas they had traditionally dominated.

Achaemenid naval campaign and assistance to Athens (393 BC)

Naval raids in Ionia

Pharnabazus followed up his victory at Cnidus by capturing several Spartan-allied cities in Ionia, instigating pro-Athenian and pro-Democracy movements.[29] Abydus and Sestus were the only cities to refuse to expel the Lacedemonians despite threats from Pharnabazus to make war on them. He attempted to force these into submission by ravaging the surrounding territory, but this proved fruitless, leading him to leave Conon in charge of winning over the cities in the Hellespont.[29]

Naval raids on the Peloponnesian coast

From 393 BC, Pharnabazus II and Conon sailed with their fleet to the Aegean island of Melos and established a base there.[29] This was the first time in 90 years, since the Greco-Persian Wars, that the Achaemenid fleet was going so far west.[29] The military occupation by these pro-Athenian forces led to several democratic revolutions and new alliances with Athens in the islands.[29]

The fleet proceeded further west to take revenge on the Spartans by invading Lacedaemonian territory, where they laid waste to Pherae and raided along the Messenian coast.[29] Their aim was probably to instigate a revolt of the Messanian helots against Sparta.[29] Eventually they left due to scarce resources and few harbors for the Achaemenid fleet in the area, as well as the looming possibility of Lacedaemonian relief forces being dispatched.[29]

They then raided the coast of Laconia and seized the island of Cythera, where they left a garrison and an Athenian governor to cripple Sparta's offensive military capabilities.[29] Cythera in effect became Achaemenid territory.[29] Seizing Cythera also had the effect of cutting the strategic route between Peloponnesia and Egypt and thus avoiding Spartan-Egyptian collusion, and directly threatening Taenarum, the harbour of Sparta.[29] This strategy to threaten Sparta had already been recommended, in vain, by the exiled Spartan Demaratus to Xerxes I in 480 BC.[29]

Pharnabazus II, leaving part of his fleet in Cythera, then went to Corinth, where he gave Sparta's rivals funds to further threaten the Lacedaemonians. He also funded the rebuilding of a Corinthian fleet to resist the Spartans.[29]

Rebuilding of the walls of Athens

After being convinced by Conon that allowing him to rebuild the Long Walls around Piraeus, the main port of Athens, would be a major blow to the Lacedaemonians, Pharnabazus eagerly gave Conon a fleet of 80 triremes and additional funds to accomplish this task.[29] Pharnabazus dispatched Conon with substantial funds and a large part of the fleet to Attica, where he joined in the rebuilding of the long walls from Athens to Piraeus, a project that had been initiated by Thrasybulus in 394 BC.[29] With the assistance of the rowers of the fleet, and the workers paid for by the Persian money, the construction was soon completed.[30]

Xenophon in his Hellenica gives a vivid contemporary account of this endeavour:

Conon said that if he (Pharnabazus) would allow him to have the fleet, he would maintain it by contributions from the islands and would meanwhile put in at Athens and aid the Athenians in rebuilding their long walls and the wall around Piraeus, adding that he knew nothing could be a heavier blow to the Lacedaemonians than this. (...) Pharnabazus, upon hearing this, eagerly dispatched him to Athens and gave him additional money for the rebuilding of the walls. Upon his arrival Conon erected a large part of the wall, giving his own crews for the work, paying the wages of carpenters and masons, and meeting whatever other expense was necessary. There were some parts of the wall, however, which the Athenians themselves, as well as volunteers from Boeotia and from other states, aided in building.

Athens quickly took advantage of its possession of walls and a fleet to seize the islands of Scyros, Imbros, and Lemnos, on which it established cleruchies (citizen colonies).[32]

As a reward for his success, Pharnabazus was allowed to marry the king's daughter.[33] He was recalled to the Achaemenid Empire in 393 BC, and replaced by satrap Tiribazus.[29]

Civil strife at Corinth

At about this time, civil strife broke out in Corinth between the democratic party and the oligarchic party. The democrats, supported by the Argives, launched an attack on their opponents, and the oligarchs were driven from the city. These exiles went to the Spartans, based at this time at Sicyon, for support, while the Athenians and Boeotians came up to support the democrats. In a night attack, the Spartans and exiles succeeded in seizing Lechaeum, Corinth's port on the Gulf of Corinth, and defeated the army that came out to challenge them the next day. The anti-Spartan allies then attempted to invest Lechaeum, but the Spartans launched an attack and drove them off.[34]

Peace conferences break down

In 392 BC, the Spartans dispatched an ambassador, Antalcidas, to the satrap Tiribazus, hoping to turn the Persians against the allies by informing them of Conon's use of the Persian fleet to begin rebuilding the Athenian empire. The Athenians learned of this, and sent Conon and several others to present their case to the Persians; they also notified their allies, and Argos, Corinth, and Thebes dispatched embassies to Tiribazus. At the conference that resulted, the Spartans proposed a peace based on the independence of all states; this was rejected by the allies, as Athens wished to hold the gains it had made in the Aegean, Thebes wished to keep its control over the Boeotian league, and Argos already had designs on assimilating Corinth into its state. The conference thus failed, but Tiribazus, alarmed by Conon's actions, arrested him, and secretly provided the Spartans with money to equip a fleet.[35] Although Conon quickly escaped, he died soon afterward.[32] A second peace conference was held at Sparta in the same year, but the proposals made there were again rejected by the allies, both because of the implications of the autonomy principle and because the Athenians were outraged that the terms proposed would have involved abandoning the Ionian Greeks to Persia.[36]

In the wake of the unsuccessful conference in Persia, Tiribazus returned to Susa to report on events, and a new general, Struthas, was sent out to take command. Struthas pursued an anti-Spartan policy, prompting the Spartans to order their commander in the region, Thibron, to attack him. Thibron successfully ravaged Persian territory for a time, but was killed along with much of his army when Struthas ambushed one of his poorly organized raiding expeditions.[37] Thibron was later replaced by Diphridas, who raided more successfully, securing a number of small successes and even capturing Struthas's son-in-law, but never achieved any dramatic results.[38]

Lechaeum and the seizure of Corinth

At Corinth, the democratic party continued to hold the city proper, while the exiles and their Spartan supporters held Lechaeum, from where they raided the Corinthian countryside. In 391 BC, Agesilaus campaigned in the area, successfully seizing several fortified points, along with a large number of prisoners and amounts of booty. While Agesilaus was in camp preparing to sell off his spoils, the Athenian general Iphicrates, with a force composed almost entirely of light troops and peltasts (javelin throwers), won a decisive victory against the Spartan regiment that had been stationed at Lechaeum in the Battle of Lechaeum. During the battle, Iphicrates took advantage of the Spartans' lack of peltasts to repeatedly harass the regiment with hit-and-run attacks, wearing the Spartans down until they broke and ran, at which point a number of them were slaughtered. Agesilaus returned home shortly after these events, but Iphicrates continued to campaign around Corinth, recapturing many of the strong points which the Spartans had previously taken, although he was unable to retake Lechaeum.[39] He also campaigned against Phlius and Arcadia, decisively defeating the Phliasians and plundering the territory of the Arcadians when they refused to engage his troops.[40]

After this victory, an Argive army came to Corinth, and, seizing the acropolis, effected the merger of Argos and Corinth.[41] The border stones between Argos and Corinth were torn down, and the citizen bodies of the two cities were merged.[39]

Later land campaigns

After Iphicrates's victories near Corinth, no more major land campaigns were conducted in that region. Campaigning continued in the Peloponnese and the northwest. Agesilaus had campaigned successfully in Argive territory in 391 BC,[43] and he launched two more major expeditions before the end of the war. In the first of these, in 389 BC, a Spartan expeditionary force crossed the Gulf of Corinth to attack Acarnania, an ally of the anti-Spartan coalition. After initial difficulties in coming to grips with the Acarnanians, who kept to the mountains and avoided engaging him directly, Agesilaus was eventually able to draw them into a pitched battle, in which the Acarnanians were routed and lost a number of men. He then sailed home across the Gulf.[44] The next year, the Acarnanians made peace with the Spartans to avoid further invasions.[45]

In 388 BC, Agesipolis led a Spartan army against Argos. Since no Argive army challenged him, he plundered the countryside for a time, and then, after receiving several unfavorable omens, returned home.[46]

Later campaigns in the Aegean

After their defeat at Cnidus, the Spartans began to rebuild a fleet, and, in fighting with Corinth, had regained control of the Gulf of Corinth by 392 BC.[47] Following the failure of the peace conferences of 392 BC, the Spartans sent a small fleet, under the commander Ecdicus, to the Aegean with orders to assist oligarchs exiled from Rhodes. Ecdicus arrived at Rhodes to find the democrats fully in control, and in possession of more ships than him, and thus waited at Cnidus. The Spartans then dispatched their fleet from the Gulf of Corinth, under Teleutias, to assist. After picking up more ships at Samos, Teleutias took command at Cnidus and commenced operations against Rhodes.[48]

Alarmed by this Spartan naval resurgence, the Athenians sent out a fleet of 40 triremes under Thrasybulus. He, judging that he could accomplish more by campaigning where the Spartan fleet was not than by challenging it directly, sailed to the Hellespont. Once there, he won over several major states to the Athenian side and placed a duty on ships sailing past Byzantium, restoring a source of revenue that the Athenians had relied on in the late Peloponnesian War. He then sailed to Lesbos, where, with the support of the Mytileneans, he defeated the Spartan forces on the island and won over a number of cities. While still on Lesbos, however, Thrasybulus was killed by raiders from the city of Aspendus.[49]

After this, the Spartans sent out a new commander, Anaxibius, to Abydos. For a time, he enjoyed a number of successes against Pharnabazus, and seized a number of Athenian merchant ships. Worried that Thrasybulus's accomplishments were being undermined, the Athenians sent Iphicrates to the region to confront Anaxibius. For a time, the two forces merely raided each other's territory, but eventually Iphicrates succeeded in guessing where Anaxibius would bring his troops on a return march from a campaign against Antandrus, and ambushed the Spartan force. When Anaxibius and his men, who were strung out in the line of march, had entered the rough, mountainous terrain in which Iphicrates and his men were waiting, the Athenians emerged and ambushed them, killing Anaxibius and many others.[50]

Aegina and Piraeus

In 389 BC, the Athenians attacked the island of Aegina, off the coast of Attica. The Spartans soon drove off the Athenian fleet, but the Athenians continued their land assault. Under Antalcidas' command, the Spartan fleet sailed east to Rhodes but it was eventually blockaded at Abydos by the regional Athenian commanders. The Athenians on Aegina, meanwhile, soon found themselves under attack, and withdrew after several months.[51]

Shortly thereafter, the Spartan fleet under Gorgopas ambushed the Athenian fleet near Athens, capturing several ships. The Athenians responded with an ambush of their own; Chabrias, on his way to Cyprus, landed his troops on Aegina and laid an ambush for the Aeginetans and their Spartan allies, killing a number of them including Gorgopas.[52]

The Spartans then sent Teleutias to Aegina to command the fleet there. Noticing that the Athenians had relaxed their guard after Chabrias's victory, he launched a raid on Piraeus, seizing numerous merchant ships.[53]

The King's Peace (387 BC)

Antalcidas, meanwhile, had entered into negotiations with Tiribazus, and reached an agreement under which the Persians would enter into the war on the Spartan side if the allies refused to make peace. It appears that the Persians, unnerved by certain actions of Athens, including supporting king Evagoras of Cyprus and Akoris of Egypt, both of whom were at war with Persia, had decided that their policy of weakening Sparta by supporting its enemies was no longer useful.[54] After escaping from the blockade at Abydos, Antalcidas attacked and defeated a small Athenian force, then united his fleet with a supporting fleet sent from Syracuse. With this force, which was soon further augmented with ships supplied by the satraps of the region, he sailed to the Hellespont, where he could cut off the trade routes that brought grain to Athens. The Athenians, mindful of their similar defeat in the Peloponnesian War less than two decades before, were ready to make peace.[55]

In this climate, when Tiribazus called a peace conference in late 387 BC, the major parties of the war were ready to discuss terms. The basic outline of the treaty was laid out by a decree from the Persian king Artaxerxes:

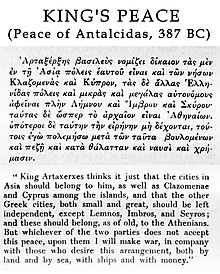

King Artaxerxes thinks it just that the cities in Asia should belong to him, as well as Clazomenae and Cyprus among the islands, and that the other Greek cities, both small and great, should be left autonomous (αὐτονόμους), except Lemnos, Imbros, and Scyros; and these should belong, as of old, to the Athenians. But whichever of the two parties does not accept this peace, upon them I will make war, in company with those who desire this arrangement, both by land and by sea, with ships and with money.[3][56][57]

According to the terms of this peace treaty:

- all of Asia Minor, with the islands of Clazomenae and Cyprus, was recognized as subject to Persia,

- all the Greek city states were to be "autonomous" (αὐτονόμους in the text), meaning prohibited from forming leagues or alliances, except Lemnos, Imbros, and Scyros, which were returned to the Athenians.[3][58]

In a general peace conference at Sparta, the Spartans, with their authority enhanced by the threat of Persian intervention, secured the acquiescence of all the major states of Greece to these terms. The terms were ratified by the city governments over the next year. The reassertion of Spartan hegemony over Greece by abandoning the Greeks of Aeolia, Ionia, and Caria has been called the "most disgraceful event in Greek history".[59]

The agreement eventually produced was commonly known as the King's Peace, reflecting the Persian influence the treaty showed. This treaty placed Greece under Persian suzerainty[60][61] and marked the first attempt at a Common Peace in Greek history; under the treaty, all cities were to be autonomous, a clause that would be enforced by the Spartans as guardians of the peace.[3] Under threat of Spartan intervention, Thebes disbanded its league, and Argos and Corinth ended their experiment in shared government; Corinth, deprived of its strong ally, was incorporated back into Sparta's Peloponnesian League.[3] After 8 years of fighting, the Corinthian war was at an end.[62]

Aftermath

In the years following the signing of the peace, the two states responsible for its structure, Persia and Sparta, took full advantage of the gains they had made. Persia, freed of both Athenian and Spartan interference in its Asian provinces, consolidated its hold over the eastern Aegean and captured both Egypt and Cyprus by 380 BC. Sparta, meanwhile, in its newly formalized position atop the Greek political system, took advantage of the autonomy clause of the peace to break up any coalition that it perceived as a threat. Disloyal allies were sharply punished—Mantinea, for instance, was broken up into five component villages. With Agesilaus at the head of the state, advocating for an aggressive policy, the Spartans campaigned from the Peloponnese to the distant Chalcidic peninsula. Their dominance over mainland Greece would last another sixteen years before being shattered at Leuctra.[63]

The war also marked the beginning of Athens' resurgence as a power in the Greek world. With their walls and their fleet restored, the Athenians were in position to turn their eyes overseas. By the middle of the 4th century, they had assembled an organization of Aegean states commonly known as the Second Athenian League, regaining at least parts of what they had lost with their defeat in 404 BC.[citation needed]

The freedom of the Ionian Greeks had been a rallying cry since the beginning of the 5th century, but after the Corinthian War, the mainland states made no further attempts to interfere with Persia's control of the region. After over a century of disruption and struggle, Persia at last ruled Ionia without disruption or intervention for over 50 years, until the time of Alexander the Great.[citation needed]

Notes

- ^ a b Hutchinson, Godfrey (2014). Sparta: Unfit for Empire. Frontline Books. p. 43. ISBN 9781848322226.

- ^ "IGII2 6217 Epitaph of Dexileos, cavalryman killed in Corinthian war (394 BC)". www.atticinscriptions.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Ruzicka, Stephen (2012). Trouble in the West: Egypt and the Persian Empire, 525–332 BC. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 81. ISBN 9780199766628.

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 556–9

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 547

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 3.2.25

- ^ a b Snodgrass, Mary Ellen (2015). Coins and Currency: An Historical Encyclopedia. McFarland. p. 125. ISBN 9781476611204.

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 3.9.2–4

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 3.4.25–29

- ^ Xenophon (3.5.1) states that Tithraustes, not Pharnabazus, sent Timocrates, but the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia states that Pharnabazus sent him. For chronological reasons, this account is to be preferred. See Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 548

- ^ Xenophon, at 3.5.2, claims that no money was accepted in Athens; the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia says otherwise. George Cawkwell, in his notes to Rex Warner's translation of Xenophon, speculates that Xenophon may be denying that money was accepted at Athens because of his sympathy for Thrasybulus (p. 174).

- ^ "Persian coins were stamped with the figure of an archer, and Agesilaus said, as he was breaking camp, that the King was driving him out of Asia with ten thousand "archers"; for so much money had been sent to Athens and Thebes and distributed among the popular leaders there, and as a consequence those people made war upon the Spartans" Plutarch 15-1-6 in Delphi Complete Works of Plutarch (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. 2013. pp. 1031, Plutarch 15–1–6. ISBN 9781909496620.

- ^ Schwartzwald, Jack L. (2014). The Ancient Near East, Greece and Rome: A Brief History. McFarland. p. 73. ISBN 9781476613079.

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 3.5.3–5

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 548–9

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 3.5.6–7

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 3.5.17–25

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Library 14.82.1–3

- ^ Hamilton, Agesilaus, p. 215.

- ^ Charles Anthon, L.L.D. (1841). A Classical Dictionary. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.2.1–8

- ^ For the battle, see Xenophon, Hellenica 4.2.16–23 and Diodorus, Library 14.83.1–2

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 3.4.27–29

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 546–7

- ^ Debord, L'Asie Mineure au IVe siècle, p. 252.

- ^ Debord, L'Asie Mineure au IVe siècle, p. 252 (note 151).

- ^ Debord, L'Asie Mineure, pp. 273, 277.

- ^ For the battle, see Xenophon, Hellenica 4.3.15–20 and Diodorus, Library 14.84.1–2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Ruzicka, Stephen (2012). Trouble in the West: Egypt and the Persian Empire, 525–332 BC. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 57–60. ISBN 9780199766628.

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.8.7–10

- ^ Xenophon. Perseus Under Philologic: Xen. 4.8.7.

- ^ a b Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 551

- ^ Xenophon Hellenica, 4.8

- ^ For these events, see Diodorus Siculus, Library 14.86 or Xenophon, Hellenica 4.4. Diodorus's account is to be preferred, since Xenophon seems to have his chronology confused, dating the merger of Argos and Corinth to before its actual occurrence; See Cawkwell's note on p. 209 of the Warner translation.

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.8.12–15

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 550

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.8.17–19

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.8.20–22

- ^ a b Xenophon, Hellenica 4.5

- ^ These events are best described by Xenophon, at 4.4.15–16, but the chronology offered by Diodorus at 14.91.3 is more likely. See Cawkwell's note to p. 212-13 of the Warner translation.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Library 14.92.1

- ^ Hurwit, Jeffrey M. (2007). "The Problem with Dexileos: Heroic and Other Nudities in Greek Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 111 (1): 35–60. doi:10.3764/aja.111.1.35. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 40024580. S2CID 191411361.

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.4.19

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.6

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.7.1

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.7

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.8.10–11

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.8.23–24

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.8.25–31

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 4.8.31–39

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 5.1.1–7

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 5.1.8–13

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 5.1.13–24

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 554–5

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 5.1.24–29

- ^ a b Tritle, Lawrence A. (2013). The Greek World in the Fourth Century: From the Fall of the Athenian Empire to the Successors of Alexander. Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 9781134524747.

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica 5.1.31

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Antalcidas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 88.

- ^ Durant, Will (1939), The Life of Greece, p. 461.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO LLC. p. 52.

- ^ Ertl, Alan (2007). The Political Economic Foundation of Democratic Capitalism: From Genesis to Maturation. Boca Raton: Brown Walker. p. 111.

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 556–7

- ^ Fine, The Ancient Greeks, 557–9

References

- Pierre Debord, L'Asie Mineure au IVe siècle, (412-323 a.C.), Pessac, Ausonius Éditions, 1999. ISBN 9782910023157

- Diodorus Siculus, Library

- Fine, John V. A. (1983). The Ancient Greeks: A critical history. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03314-6.

- Fornis, César, Grecia exhausta. Ensayo sobre la guerra de Corinto (Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2008).

- Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta's Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1979.

- Hornblower, Simon (2003). "Corinthian War". In Simon Hornblower; Antony Spawforth (eds.). The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd, rev. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 391. ISBN 978-0-19-860641-3.

- Perlman, S. "The Causes and the Outbreak of the Corinthian War," The Classical Quarterly, 14,1 (1964), 64–81.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece

- Xenophon (1890s) [original 4th century BC]. . Translated by Henry Graham Dakyns – via Wikisource.

- Print version: Xenophon, A History of My Times, Translated by Rex Warner, notes by George Cawkwell. (Penguin Books, 1979). ISBN 0-14-044175-1