Fires in the Paris Commune

Panorama of fires in Paris from May 23 to 25 - Lithograph by Auguste Victor Deroy, Musée Carnavalet, Paris. |

The fires of Paris during the Commune were the premeditated destruction of monuments and residential buildings in Paris mainly during Bloody Week, the period when Paris was recaptured by the Versailles army from Sunday, May 21 to Sunday, May 28, 1871.

Most of these fires were set by Communards (or Federates), especially between May 22 and 26. They set fire to major Parisian monuments such as the Tuileries Palace, Palais-Royal, Palais de Justice and Hôtel de Ville, but spared others such as Notre-Dame Cathedral. They also set fire to private homes, to protect their barricades from the advancing Versaillais. Setting fire to Paris's great monuments was a strategy of despair, an act of appropriation and purification, and a kind of apocalyptic feast, as the Communards fought their last battles in the streets.

Despite attempts to organize, these fires were lit in the very last days of the Commune, when it was in full decay, and decisions were partly local initiatives, at a time when the usual points of reference, including sensory ones, had been turned upside down. After their defeat, the Communards did not all accept responsibility.

These fires formed a nodal point in the memory of the Commune. In the eyes of the Versaillais, they demonstrated the barbarity of the Communards, particularly the women of the Commune, around whom the myth of the pétroleuses was built. The resulting ruins were not immediately rebuilt and became the object of romantic and touristic appropriation, including numerous photographs. The massive disappearance of archives consumed in the fires deprived Paris of part of its memory.

Paris under siege (September 1870-May 1871)[edit]

Prussian bombing and the barricade[edit]

France declared war against Prussia on July 19, 1870. After Napoleon III's army surrendered at Sedan, Parisians proclaimed the Republic on September 4, 1870, but the war continued and, from September 20, 1870, Paris was besieged by the Prussians.[1] Prussian cannons regularly bombarded Paris, destroying many houses, particularly on the Left Bank. The din of the cannonade instilled fear in Parisians.[2] The fighting around Paris during the autumn and winter of 1870-1871 led to several disasters. From September 1870, buildings, bridges, farms, millstones, and forests were burned by both armies. In January 1871, Paris was hit by outbreaks of fire, quickly brought under control as a result of bombardment by the Prussians.[3]

Ever since the French Revolution, a major reference point for the Communards, the fear of seeing the enemy destroy Paris had been growing, and it permeated the minds of many Parisian revolutionaries throughout the 19th century. The federates were to transform this fear into a determination to destroy and reconfigure Paris, starting with the barricade.[4] Indeed, the barricade, while a major element in the defense of Parisian streets during the Commune, was also first and foremost an attempt to control space and destroy the urban fabric, a bricolage of different objects, some of which came from inside the home, removing the difference between private and public space.[5][6][4] This was the beginning of the process that led to the burning of part of the city by the Communards.[4]

The siege of the Versailles army[edit]

Following the insurrection of March 18, 1871, which sparked off the Paris Commune, France found itself in a situation of civil war, on the one hand, the government led by Adolphe Thiers, who had fled to Versailles, where the National Assembly also sat in support of him, and on the other the Paris Commune, which ruled Paris alone,[7] despite attempts by insurrectionary communes in the provinces.[8]

The second siege of Paris was led by Versailles troops from April 11 to May 21, 1871. Adolphe Thiers adopted a cautious strategy of gradual investment in the capital, as it was protected by its walls and considered a fortress.[4] The Versailles government took no chances. It sought to avoid any failure, for fear of being overthrown by the National Assembly, of the army disbanding, of uprisings in major cities, or of Prussian intervention.[9]

The Versailles army bombarded the outskirts of Paris, in particular the forts protecting the city, much more intensively than the Prussians had done since Versailles' objective was to neutralize the forts and the city walls. This destruction strengthened the determination of the Communards, even to destroy the city themselves if they were unable to defend it.[4]

Fires broke out in the suburbs and west of Paris, in Auteuil, Passy, Courbevoie, Asnières, Levallois-Perret, Clichy, Gennevilliers and Montrouge. They were caused by Versaillais bombardments or fires set by Communards. The federates had incendiary plans for Bagneux and Vanves but had no time to implement them due to the speed of the Versaillais conquest. In all, few fires were set in western Paris.[10]

The fires of Bloody Week[edit]

During Bloody Week, the chronology of destruction by fire is that of the recapture of Paris by Versailles troops, from west to east, from Sunday, May 21 to Sunday, May 28, 1871.[11]

West, Monday, May 22[edit]

After an initial fire in the Champ-de-Mars barracks,[12] fire broke out on the evening of Monday May 22 in the attic of the Ministry of Finance, then on rue de Rivoli,[12][13][11] ignited by Versailles shells.[12][13] It was extinguished by the Commune fire department.[12]

The responsibility for this fire at the Ministry of Finance was an important issue in the post-Commune debates. Indeed, as it was the first large-scale fire, the camp that started it was accused by the others of having caused the subsequent fires. All the exiled Communards blamed Versailles cannon shells. So did the Versaillais Catulle Mendès.[14] According to anti-Communard writer Maxime Du Camp, there were two successive fires at the Ministry of Finance, the first caused by Versailles shells on Monday, May 22, extinguished by the federates, then a second the following day, which they set themselves.[15][16]

The first major fires, Tuesday, May 23[edit]

Until May 23, Versailles troops faced no serious resistance. The first major fires coincided with an intensification of the Communard defense.[17] After preparations were completed at around 6 p.m. on May 23, Communards burned several monuments the following night:[18] the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur, the Palais d'Orsay (home to the Cour des Comptes), the Caisse des Dépôts, the Palais des Tuileries and nearby streets.[12][11][18] Rue de Lille was one of the streets most affected by the fires.[16] The Versaillais decided to wait until the following day to bypass the fires.[17]

The Tuileries was the headquarters of insurgent general Jules Bergeret, who led the fighting there with six hundred men. Faced with the advance of the Versaillais,[16] he decided to set fire to the palace, along with Alexis Dardelle, Étienne Boudin, and Victor Bénot.[19][20][21] Dardelle was the governor of the Tuileries Palace, appointed on March 22, 1871, by the Commune.[22] On May 23, the fire was prepared with carts of gunpowder, liquid tar, turpentine and petroleum.[23][21] Using these flammable substances, the federates sprayed the drapes, curtains and parquet floors, and placed barrels of gunpowder[24] in the salon des maréchaux and at the foot of the Great Staircase, while Dardelle organized the evacuation of horses, harnesses and valuables, and ordered the employees to leave, announcing an imminent explosion.[22] The Communards lit the fire with large flaming poles.[24] Later, Dardelle and Bergeret watched the flames from the Louvre terrace.[22] The Tuileries burned until Friday May 26.[17]

Émile Eudes sets fire to the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur,[19][20] on the orders of the Comité de salut public.[22] The order to set fire to the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur on May 23 was also attributed at his trial in 1872 to Émile Gois,[25] but evidence is lacking.[26] On the same day, the advance of the Versaillais was also slowed down by fires lit in the Madeleine district and at the Croix-Rouge crossroads[notes 1] defended by Eugène Varlin and Maxime Lisbonne.[17]

Around the City Hall, Wednesday, May 24[edit]

On Wednesday, May 24, fires were set during the day at the Louvre[11] - despite, as he later asserted, Bergeret's opposition[20] - in houses on rue Saint-Honoré, rue de Rivoli and rue Royale, where seven people died of asphyxiation, in the Palais-Royal (only slightly damaged), the Hôtel de Ville (destroyed), the Palais de justice, the Conciergerie, the Préfecture de police, the Porte-Saint-Martin theater (destroyed)[11] and the Théâtre-Lyrique.[19] Groups of arsonists prepared pyres and barrels of gunpowder and doused the walls with petrol before lighting the fire.[19] The fire at the Palais de Justice was caused by the collapse of a large calorifier filled with water used for heating, the rupture of its reservoir causing a flood.[27] In a hastily-written report on May 24, Édouard Gerspach, chief of staff at the Ministry of Fine Arts, gives a detailed account of the state of the Tuileries and the Louvre.[23]

The order to burn down the Hôtel de Ville was given by Jean-Louis Pindy, who had been its governor since March 31,[28] while the order to set fire to the Préfecture de Police and the Palais de Justice came from Théophile Ferré. Both orders were given at around 10 a.m.[12][29][19] Victor Bénot played a major role in the fire at the Palais-Royal[20] and is said to have set fire to the Louvre library.[17] The fire set the same day at the Place du Château-d'Eau slowed the Versailles advance.[17] In the afternoon,[29] Maxime Lisbonne blew up the powder magazine in the Luxembourg Garden.[20]

On Tuesday May 23 and Wednesday May 24, the federates also set fire to many of the houses adjacent to their barricades, in rue Saint-Florentin, rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, rue du Bac, rue Vavin, place de l'Hôtel-de-Ville, boulevard de Sébastopol,[13][30] etc. In addition to the buildings already mentioned, the fire also totally or partially destroyed the Archives de la Seine, the artillery headquarters on Place de l'Arsenal, the Protestant temple on rue Saint-Antoine and the barracks on Quai d'Orsay.[19]

East of Paris, May 25 and 26[edit]

On Thursday, May 25, the fire at the Hôtel de Ville ends, while that of the Greniers d'abondance, a food depot on Boulevard Bourdon, begins.[11][31]

On Friday, May 26, the docks at La Villette - where large quantities of explosives are stored[31] - are on fire, and the Bastille column is surrounded by flames. On Saturday May 27, fires were lit in Belleville and Père-Lachaise.[32]

The capsule on rue de l'Orme, the Délassements-Comiques theater, the Bercy church, the 12th arrondissement town hall - in 1873, Jean Fenouillas was shot for these two fires[33] - the Gobelins factory[19] and houses near the barricades, rue de Bondy, boulevard Mazas,[notes 2] boulevard Beaumarchais[13][30] etc., also burned, either partially or completely.

Fires were generally confined to the buildings to be burned, and accidental spread was rare. Haussmannian breakthroughs are effective firebreaks.[17]

Heat and light, smells and sounds[edit]

During the bloody week, employees at the Luxembourg observatory continued to take weather readings, except on Wednesday, May 24, when the observatory was on the front line. We therefore know the weather in Paris during the fighting and fires. From Sunday, May 21 to Thursday, May 25, the temperature (measured at midday) rose from 18 °C to 25 °C. It was unseasonably warm. The weather was dry, with moderate to light winds.[34]

- Fires at Tuileries and Hôtel de ville

-

Incendie des Tuileries - Lithograph by Léon Sabatier and Albert Adam Paris et ses ruines, 1873 - Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris.

-

Hôtel de ville fire - Lithograph by Léon Sabatier and Albert Adam Paris et ses ruines, 1873 - Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris.

-

Theodor Josef Hubert Hoffbauer L'incendie de l'Hôtel de Ville de Paris. Paris through the ages, Firmin-Didot, 1885.

Many Parisians climbed to the top floor or rooftop of their building to get a panoramic view of what's going on. It's the only way to get the full measure of the new outbreak. The blazes are terrifying, especially at night. An anonymous Parisian on rue Saint-Denis described:[35]

The sky was red, and every moment you could see that the brightness was increasing and spreading. It was in this night, forever doomed, that the federates set fire to everything, leaving nothing but ruins for the victors [...] a fiery, infernal horizon.

The spectacle shocked and frightened, as this young American woman testified: "I was often frightened during the Commune, but I don't remember anything as terrifying as the fires". Fear and exasperation fueled the Versailles soldiers' hunt for Communards.[36] Faced with the fires, the reactions of anti-Communard Parisians oscillated between two poles. In neighborhoods reclaimed by the Versailles army, angry crowds attacked Communard prisoners, mainly because of the fires. The other reaction was silence and astonishment. As Ludovic Halévy wrote: "We can't find a word to say".[35]

On Friday, May 26, the weather changed. The wind shifted and the temperature dropped to 17 °C.[34] The sky became overcast and rain fell. The showers soaked the fighters but made it easier to fight the flames.[37] The wind blew the smoke westwards, but as the fighting was now taking place in the east of Paris, the main fires burned behind the fighters, who were therefore not bothered by the smoke.[35]

The following day, Saturday, May 27, began in fog, followed by heavy, steady rain.[38] It helped to extinguish the fires, while the Versaillais victory was no longer in doubt. Some saw it as a divine sign. On Sunday, May 28, it stopped raining and the temperature rose to 20 °C. The wind blew strongly eastwards, fanning the last fires as the Commune fought its final battles.[34]

Monuments spared[edit]

Adjacent to the Palais de Justice, the Sainte-Chapelle escaped the fire. In Notre-Dame cathedral, the federates may have started a fire with chairs and benches, which was quickly extinguished by local residents.[11] At least, that's the scenario recounted by the Versaillais. More likely, the Communards themselves decided not to burn the cathedral, to avoid causing casualties among the wounded Federals sheltering in the nearby Hôtel-Dieu, and because Notre-Dame was not one of their objectives: it was not a central monument for them, unlike the Hôtel de Ville.[39] Generally speaking, the Communards did not set fire to churches, which may seem surprising given their anti-clericalism. We don't know exactly why.[14] As for the Hôtel-Dieu, by the time the sick had been evacuated, it was too late to set fire to it, as the area had passed under Versailles control.[11]

The Banque de France was not set on fire, thanks to its deputy governor, the Marquis de Ploeuc, and Charles Beslay, Commune commissioner, who opposed any attempt.[40] Beslay, exiled in Switzerland, made his statement in Le Figaro in 1873: "I went to the Bank to protect it from any violence by the Commune's exaggerated party, and I am convinced that I have preserved for my country the institution that constituted our last financial resource".[41][42]

The Archives nationales, the Bibliothèque Mazarine, and the Bibliothèque du Luxembourg were also saved by Communards.[19] The director of the Archives nationales, Alfred Maury, and Louis-Guillaume Debock, the Commune's delegate at the Imprimerie nationale, succeeded in opposing the fire plans.[43] Debock was in charge of the Imprimerie Nationale, next door to the Archives nationales, and ensured that the latter would not be set on fire or hit by Communard shells.[44] Debock went so far as to threaten with his revolver the commander who was planning to burn down the Imprimerie nationale on Wednesday May 24. Appointed by the Commune, Debock was determined to fulfill his mandate. The commander who wanted to set fire to the building claimed to be a member of the Comité de salut public. This episode reveals the disorganization of the Commune in its final days.[14]

According to historian Jean-Claude Caron, a total of between 216 and 238 buildings were destroyed or damaged by the fire. So not all of Paris was on fire, even if the buildings that burned were symbolically very important. The last fires were extinguished on June 2. Apart from the seven who suffocated, accounts of direct victims of the fires are not very credible, as they are anti-Communard.[32] Houses were usually set on fire after their inhabitants had been evacuated.[14] Based on complaints and compensation after the bloody week, Hélène Lewandowski counts at least 581 buildings damaged to varying degrees, including 186 houses and 32 public buildings as a result of the fires.[16]

The Commune and the fire[edit]

On April 22, the Commune set up a Scientific Delegation, headed by François-Louis Parisel, a pharmacist.[45][46][47] According to his proposal, he was to deal with food products, aerostats, poisons and means of destruction.[45] The Scientific Delegation's account books show that Parisel bought materials in small quantities for experiments, but that he does not have large stocks of inflammable material.[47] He calls for the invention of weapons and devices with chemical projectiles,[46] but the projects presented by citizens are rather unrealistic.[47] On May 16, he was asked to set up teams of "Fuseen artillerymen". Two days later, there were officially twenty-seven of them.[46]

On Tuesday, May 23, in the fighting in Paris, the Comité de salut public ordered Paris municipalities to collect "all chemical, inflammable and violent products found in their arrondissement, and to concentrate them in the 11th arrondissement".[20] The following day, Wednesday, May 24, he decreed the creation of brigades of fuséens, 400 men commanded by Jean-Baptiste Millière, Louis-Simon Dereure, Alfred-Édouard Billioray, and Pierre Vésinier, with the mission of setting fire to "suspicious houses and public monuments". Although these attempts at organization were too late to be effective,[46] the Commune nevertheless had time to build up reserves of incendiary products (barrels of petrol, incendiary projectiles, stocks of gunpowder) in eastern Paris, from La Villette to Charonne, which Versailles troops recovered after their victory.[48]

The Commune's fighting was carried out in a continuous balancing act between organization and spontaneity.[49] The Commune's orders to light fires for urban warfare came late and were limited to the precise locations where the fighting was taking place. More generally, it was difficult to distinguish between collective responsibility and individual initiative, when the Commune's governing bodies were no longer meeting in the middle of the fighting.[20] General disorganization and local initiative were the rule. The various groups of Communards, usually numbering around a hundred men, were isolated, surrounded, and outnumbered. Only the most determined federates were fighting.[50] Many fireplaces were lit on the spur of the moment, with local fighters spreading kerosene.[14]

Anti-Communard writings reflect rumors assimilating fires to organized crime: fires were set by thousands of incendiaries, men, women, and children; the sewer system was mined; labels were affixed to houses to be burned; eggs were filled with petroleum capsules; free balloons were weighted down with incendiary products, etc. These rumors are denied by the facts, but the use of fire is here used to disqualify the war waged by the Communards as a dirty war that did not respect the laws. These rumors are denied by the facts, but the use of fire is used here as an argument to disqualify the war waged by the Communards, likened to a dirty war, which does not respect the laws of war.[48]

The Versailles press described national guards bringing in oil tanks and "petroleum firemen", especially for the Palais-Royal fire, but the 117 firemen arrested after the bloody week were almost all released, and it seems that they overwhelmingly refused to use their pumps to douse the buildings with oil. Some even tried to put out the fires in the middle of the fighting.[20] Immediately after the bloody week, these rumors fed and were fed by a climate of fear, described by Émile Zola in his sixth letter published by the newspaper Le Sémaphore de Marseille on May 31:[51]

"After the Red Terror, a new and particular terror is now reigning in Paris, which I'll call the Terror of Fire. The stubborn belief of the majority is that the incendiaries will not stop, even after order is restored, and that, for many months to come, fires will occur in every part of Paris [...]. Half of Paris is afraid of the other half. [...] If you have the misfortune to stop in front of a wall, you immediately see dark eyes fixed on you and spying on your movements."

Communards and responsibility for fires[edit]

After taking control of the town, the Versailles army carried out a veritable arson hunt in the streets and banned the oil trade.[32] Judicial records show 175 people incriminated for setting fires. Of the 40,000 or so federates who appeared before the military courts after the Commune, only 41 were tried for arson. Of these, 16 were sentenced to death (of whom 5 were executed, the others having their sentences commuted to imprisonment or hard labor) and 24 to hard labor. These included Baudoin, convicted of setting fire to Saint-Eloi church, Victor Bénot for the Tuileries fire, and Louis Decamps for the Rue de Lille fire. To this must be added convictions in absentia, bringing the total to around one hundred. This figure does not take into account the real number of arsonists, which is much higher, as they are much more difficult to apprehend than the fighters, who were arrested with their weapons drawn.[52]

At first, incendiaries were assimilated to common criminals, and as such were excluded from Henri Brisson's first unsuccessful amnesty proposal for the Communards in September 1871. The plenary amnesty finally passed in 1880 made no further distinction.[53]

After their defeat, the Communards did not all accept the same degree of responsibility. Vésinier, for example, claimed that Versailles shells were the only cause of the outbreaks of fire; however, this maximalist assertion met with little response. On the other hand, those of Arthur Arnould, Gustave Lefrançais, and Jean Allemane, who point to the responsibility of former Second Empire agents who had an interest in making documents proving their involvement disappear, were more successful.[54]

Lefrançais only recognized the Commune's responsibility for the burning of the Tuileries and the Grenier d'abondance, which he approved of, but not for the destruction of the Hôtel de Ville, which he condemned. Personal grudges and settling of scores were also incriminated: fireplaces lit in stores by former employees, according to Jules Andrieu, and house fires set by their owners to remove evidence of bankruptcy or to collect compensation, according to Louise Michel.[54] Some Communards justify or approve of burning, such as Eugène Vermersch, Victorine Brocher,[54] Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray or Gustave Paul Cluseret.[55] For them, fire is a legitimate revolutionary means.[54]

Tactical choice, strategy of despair, and apocalyptic sovereignty party[edit]

From the end of the bloody week, the attribution of responsibility for the fires between the federates and the Versaillais became an important political issue. Apart from the fire at the Ministry of Finance and Belleville, which were undoubtedly started by red balls fired from Versaillais cannons, the vast majority of the fires were undoubtedly started by the Communards.[54]

In previous revolutions, such as those of July 1830 and February 1848, fires had been set, but these were of limited scope, due to the rapid victories of the revolutionaries.[56] The war waged by the Commune was a defensive war in an urban environment. In this context, setting fires was a tactic that complemented the defense of a territory structured by barricades.[46] Setting fire to the houses supporting the barricade was a response to the Versailles tactic of "chemininement", which consisted in encircling the barricade by advancing through the buildings, piercing the walls. As Louise Michel[39] put it, the Communards sought to "oppose the invaders with a barrier of flames".[17] When the barricade was about to be taken by the Versaillais, it was evacuated by burning the surrounding houses.[46]

On Wednesday May 24, for example, the theater at Porte Saint-Martin was set on fire to protect the Federates' withdrawal to Place de la Bastille and Place du Château-d'Eau.[notes 3] The next day, defenders of the Rue Thévenot barricade caused panic by setting fire to a wine merchant's shop.[57] Fire was the last weapon,[12] even if some Communards, like Jules Andrieu, condemned it.[54]

However, the necessities of combat were only part of the explanation.[13] For the Versaillais, the Communards lit these fires in a sort of strategy of desperation, summed up in the slogan attributed to Charles Delescluze: "Moscow rather than Sedand ".[54][56] On May 17, in a speech delivered at Saint-Sulpice church, Louise Michel proclaimed: "Yes, I swear it, Paris will be ours or Paris will no longer exist!".[58] For General Appert, the head of military justice who condemned the Communards: "There's nothing to indicate an overall plan. It was, I believe, only at the end that the insurgents, having lost all hope, decided to set fire to Paris ".[59][16]

On a deeper level, the federates attacked the buildings that symbolized, in their eyes, power: that of the monarchical state, that of centralized government, that of the Church, that of the army.[13] The burning of symbolic monuments was, in fact, a final act of sovereignty, of appropriation as well as purification, a form of revolutionary iconoclasm,[39] following on from the demolition of the Vendôme column and Adolphe Thiers' townhouse, which took place before Bloody Week.[50] Communard Paul Martine, in his Souvenirs d'un insurgé, describes his state of mind during the Bloody Week as follows:[19]

"Tomorrow, the bandits of Versailles will re-establish absolute royalty, the white flag, the reign of the gentleman and the priest. [...] Our defeat marks the death of the Revolution throughout the world. Well, no! They will have nothing of our joy and honor! We incinerate our flag rather than surrender it to the enemy. Well, yes! We'll incinerate Paris, rather than return it desecrated, defeated, enslaved to the Prussians and the Bourbons!"

During the Commune, the Hôtel de Ville was the main place of collective government, where the Conseil de la Commune was installed. The Commune is a project for a universal federation based on the scale of each city. Paris City Hall symbolizes this ambition. The Communards set fire to it because they refused to let it fall into the hands of those who were the enemies of this project.[60] For other federates, such as Jules Andrieu, the Hôtel de Ville had little value because it was a place of betrayal, where the people had been robbed of their revolutions since that of 1830.[55][39]

For the Communards, the burning of the Tuileries was an opportunity to do away with one of the symbols of the Second Empire,[61] and the fire, certainly the most significant of all those set during the bloody week, was part of a kind of apocalyptic celebration.[62] It was an extension of the festivities organized by the Commune on May 20 at the Tuileries, with a huge free concert that drew large crowds. On May 24, Parisians flocked to the Buttes-Chaumont to watch the flames devouring the Tuileries, and to express their joy. Gustave Lefrançais confessed: "Yes, I'm one of those who jumped for joy when I saw that sinister palace go up in flames".[62] Parisians often drew parallels between the destructive flames and the festive illuminations.[35]

In short, the Communards set fire to Paris for three main reasons: to better defend themselves in a disorganized situation, to assert their ownership of the monuments and the city, and to take revenge on the Versaillais and deserters. According to Jules Andrieu, setting fire to the city was "an order given by no one, accepted by everyone".[50]

Images, imagination, and memory of fires[edit]

Wild madness, divine punishment, and flames in the night[edit]

From the end of the Commune, it became the focus of a war of words and images. The violence of the fires lit during the bloody week was central to the descriptions of the Versaillais, who drew on the imagination of the orgy, wild and foreign, with reminders of the Moscow fire of 1812. Fire is the weapon of "negro revenge", of Barbarians, Huns, Tamerlane... The Commune is described as Nero's child.[63] According to Paul de Saint-Victor:[64]

"In the afterglow of the Paris fire, the world saw how similar tyranny and demagogy are. Nero, through the centuries, passed his torch to Babeuf."

In these speeches, the revolutionary is ultimately no more than a barbarian, an enemy of beauty.[16] He is also a madman, and the fire is proof of this insanity. This interpretation can be found in the works of writers well into the 1890s, whether Edmond de Goncourt in his journal, Paul de Saint-Victor in Barbares et Bandits, Alphonse Daudet in Contes du lundi or Émile Zola, in La Débâcle.[21] The Versaillais witnesses did not understand that many of the fires could be explained by the urgent need to defend the barricades, but they did understand that this was a celebration of sovereignty, the Commune's last show of power.[65] For this, the Communards deserve to be punished. The lexical field of hell and divine punishment is invoked, for example by Catholic polemicist Louis Veuillot:[63]

Paris writhes in the flames ignited by the ideas and hands of its sons: the last word of the Commune, itself the last word of the Revolution! [...] Neither Babylon, nor her daughters, nor old Sodom, nor old Gomorrah, have perished so by their own hands. Rain of fire, rain of sulfur, showers of liquid fire, waterspouts of burning iron! [...] God remained silent before the destruction, as he had been since the blasphemy. Jerusalem is obsolete. Since Christ, no city has fallen from this death.

In Versailles' writings, comparisons with the biblical Apocalypse are frequent. This metaphor demonstrates the horror inspired by the Paris Commune,[66][67] while at the same time emphasizing Paris's ability to move forward.[66]

Among the recurring themes of Versailles' texts, the misuse of oil by the Communards appears to be a veritable obsession. The "flotsam and jetsam of oil" is described. Oil, a liquid drawn from the depths of the earth, is equated with hell. For Catholic writers in particular, its use by the Communards seems to demonstrate a link between misguided technical progress and revolution, which serves to underpin a conservative discourse. The same characteristics can be found in the myth of a Paris in danger of exploding due to a network of mines laid by the Communards.[68] In both cases - oil and mines - rumors fed the resentment and fear of Versailles soldiers and contributed to the violence committed.[69]

In their pictorial works produced in the immediate aftermath of Bloody Week, artists such as Jules Girardet, Georges Clairin, Édouard Manet, Alfred Darjou, Gustave Courbet, Gustave Boulanger, and Alfred Roll sought to depict current events to document them. These artists turned to naturalism to bear witness to what they had seen.[70]

Panoramic views of the fires, such as Numa fils' Paris incendié or Charles Leduc's La Cannonnière La Farcy, show the Seine irradiated and reddened by the reflections of the flames as if the river were turning into the lava of a volcano, to which Communard Paris is often compared.[71] The fires of the Commune are most often depicted at night, the darkness responding to the supposed darkness of the Communards' souls. Paris is depicted lit up as if in broad daylight, even by a Communard like Pierre Vésinier:[63]

"A long line of fire lit up Paris as if in broad daylight, separating and bisecting it on the banks of the Seine. The flames were so high they seemed to touch the clouds and lick the sky. They were so intense, so brilliant, that next to them the sun's rays looked like shadows. The hearths from which they escaped were more red-white, more incandescent than the most ardent furnaces [...]; and, from time to time, an immense explosion was heard, immense sprays of flames, flaming globes, sparks, rose to the sky, piercing the clouds, much higher even than the other flames of the fires; they were immense bouquets of fireworks. We had never seen anything so terrifyingly sublime."

In La Débâcle, a novel published more than twenty years after the Commune, Émile Zola also returns to this night mingled with day:[71]

"For three days now, it's been impossible to cast a shadow without the city seeming to catch fire again, as if the darkness had blown over the still-red firebrands, rekindling them, sowing them to the four corners of the horizon. Ah! this hellish city, glowing from dusk onwards, lit for a whole week, illuminating the nights of the bloody week with its monstrous torches! [...] In the bleeding sky, the red districts, ad infinitum, rolled the stream of their ember roofs."

Artists and writers share a common theme: the lexicon used by writers to describe the fires of Bloody Week calls for bright, vivid colors, which are also found in the palette of the artists who depicted these events.[71]

In the history textbooks published in the 20th century, depictions of the fires of Bloody Week, for which the Communards were entirely responsible, formed a major part of the iconography of the pages devoted to the Commune. Barricades and fires embodied the violence of the Commune, especially up until the 1960s when more emphasis was placed on images of those shot.[72]

The Pétroleuses myth[edit]

From the moment of their victory, the Versaillais built up the myth of the pétroleuses, highlighted in 1963 by Édith Thomas's pioneering book of the same name.[73] Based on the few examples of women taking part in fires,[74] the Versailles press told numerous stories of women arrested just before starting a fire.[75] A word was coined to describe them, and Théophile Gautier justified its invention: "Pétroleuse, hideous word, which the dictionary had not foreseen: but unknown horrors require appalling neologisms".[76] But the facts did not support this line of argument. Communard women were arrested as canteen workers, ambulance drivers, furnace or hospital workers, or whistle-blowers, but very few were arrested as arsonists. Around 130 women were convicted of taking part in the Commune, but mainly as fighters on the barricades,[74] in a scattered manner, since the women's barricade at the foot of Montmartre is another myth.[77]

On September 4, 1871, five women accused of setting fire to the Hôtel de la Légion d'Honneur were put on trial. Three were condemned to death (their sentences were later commuted), despite very flimsy evidence. The description of these women is particularly demeaning. The Rétiffe woman's nose is "slightly budded, indicative of poor temperamental habits". We note the "insolent and cynical eye" of the Suétens woman. As for the Bocquin woman, she is described with "a sickly, devious aspect that is both frightening and pitiful at the same time".[74]

The Communards denied the existence of pétroleuses. Louise Michel asserted: "The wildest legends ran about the pétroleuses. There were no pétroleuses". Karl Marx maintained that it was indeed men who started the fires.[74] For the Versaillais, Communard women were considered worse than Communards, who were at least given the excuse of alcoholism: "More relentless than men, they acted with more cynicism; for while the former often drew a stimulant for their energy from alcohol abuse, the latter found this stimulant in their exaltation".[78]

The myth of the pétroleuses corresponds to a pre-existing perception of female violence.[74] The female rioter, more dangerous than the male, has been a figure of popular emotion since the end of the Ancien Régime. The figure of the pétroleuse is, therefore, a reactivation, reminiscent of the knitters of 1793. For the Versaillais, it represents a major transgression of the female figure, through an inversion of sexual roles.[64] Rather than recognizing courageous fighters, it's easier to think of women in fury, torches in hand, fire being the weapon of the weak and the mad. As a result, images of the Communard woman oscillate between two poles: the cantinière and the pétroleuse. The myth spread through media: the press, popular songs, printed images, etc. The pétroleuses are depicted as ugly, dressed in rags and forming small, disturbing groups, "brigades de pétroleuses".[74]

- Pétroleuses images

-

Une pétroleuse. Lithograph by Adrien Marie, engraved by Froment, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, 1871.

-

Les pétroleuses et leurs complices, drawing by Frédéric Lix in Le Monde illustré, June 3, 1871. Gallica.

-

Une pétroleuse. Lithograph by Paul Klenck, Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

-

La Commune: série de portraits avec notice biographique, Paris, Mordret, 1871. Gallica.

-

The Commune. Lithograph, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, 1871.

The insistence in the iconography on the petroleum-filled milk cans of the pétroleuses manifests Versailles' phobia of the metamorphosis of mothers into incendiary madwomen.[64] The women of the Commune are shown as prostitutes or as hysterical and stupid. From allegories of Liberty, the engravings move on to images considered vulgar because they show the free women of the people. The petrolhead with a torch in hand is the antithesis of knowledge or Liberty, whose torch lights up the world.[79]

Burnt memory[edit]

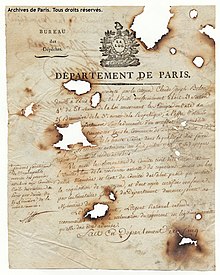

These fires were also responsible for the loss of valuable archives, both those of the City of Paris and those of the Palais de Justice.[80] The destruction of the Palais de Justice archives was massive, particularly those of the civil registry (from the outset) and those of the Cour de cassation. Along with the Hôtel de Ville, the civil records of Parisians burned down, leaving only the records kept in the arrondissement town halls since 1860.[43] Thus disappeared the parish registers dating back to the 16th century and the civil registers from 1792 to December 31, 1859. Duplicates of these registers did exist, but they were kept in the Palais de Justice and were destroyed by fire. Between 1872 and 1897, a commission was set up to reconstitute the civil records of Parisians, restoring more than 2.5 million records - a third of those that had disappeared.[81] The commission made use of family papers submitted by private individuals, Catholic registers kept in Paris parishes since the Revolution, death tables from the registry office, etc.[82]

A large part of the Assistance publique archives disappeared when its buildings, close to the Hôtel de Ville, were engulfed in flames. The same was true of part of France's financial archives,[43] as well as most of the archives of the Prefecture de Police, only a portion of which was saved along with the Venus de Milo in a vault set up on rue de Jérusalem to protect the famous statue during the siege of Paris by the Prussians.[83][84][85]

Rich libraries also burned, including those of the Louvre, Hôtel de Ville, and the Bar Association.[80] The destroyed Louvre library housed almost 100,000 volumes, while the Hôtel de Ville library held around 150,000. In the Louvre cabinet, many ancient manuscripts dating back to Charles the Bald were lost. Along with the burned monuments went works by great artists such as Charles Le Brun, Antoine Coysevox, Ingres, Eugène Delacroix, etc.[43] In the Gobelins factory, seventy-five tapestries dating from the 15th to 18th centuries burned, including some major pieces.[86] These fires of memory were a major element of the criticism leveled at the Commune.[43]

Ruins and reconstruction[edit]

Ruin tourism[edit]

By June 1871, the Parisian ruins had become a popular destination for strolling. With family or friends, crowds of Parisians flocked to the site, despite the risk of falling rocks and unstable facades. English tourists also made the ruins their destination.[87]

Publishers provide illustrated maps, such as Paris, ses monuments et ses ruines, 1870-71.[16] Tourist guides, such as Guide à travers les ruines or Itinéraire des ruines de Paris, offered tours that lasted several days from place to place.[88][89] Comparisons with natural sites or other cities are numerous.[88]

These books offer a glimpse of a battered but reborn city. They focus on the center of Paris, from the Arc de Triomphe to the Bastille. The ruins visited by Parisians are mainly confined to the area between Place Vendôme and Bastille, on the right bank. Texts and photos focus primarily on the Tuileries and the Hôtel de Ville.[90] Visitors collected shell fragments and, above all, monuments.[91]

Numerous collections of photographs were published from 1871 onwards, responding to and stimulating public curiosity.[88] These collections claim to show reality, but they are the result of choice, as are all the photographs taken in connection with the Commune.[92] The images showing the bloody week are focused on two subjects, the massacres, and the ruins, tending to demonstrate, according to a Manichean vision, that the Commune is a dead end, and thus obliterating its chronology and possibilities.[93] According to Hélène Lewandowski, the photographic representation of the ruins confines "the Commune within the confines of the Semaine Sanglante, and [condemns] it to the reputation of an incendiary and iconoclastic revolution".[94]

In 1871-1872, half the photographs in the legal deposit were related to the Commune. Two-thirds of them depict the ruins of Paris.[95] A total of 735 shots were taken of them.[96] From the Second Empire onwards, photographers were mobilized for official propaganda, and, in 1871, the authorities reactivated this function: photographers had to show a very damaged Paris.[39] During the Commune, many photographers, like Eugène Disdéri, were out of business. They were either absent from Paris or in hiding. As soon as the bloody week was over, they took and published many photos, meeting the need for the development of ruin tourism.[97]

The tight framing of the heavily damaged buildings, with no view of the surrounding area, reinforces the false impression of a largely destroyed city.[95] But while these photographs support the Versailles writings by showing a destroyed Paris, they are also the expression of an aesthetic of ruin. The Grenier d'abondance, a utilitarian building with no symbolic charge, is revealed as a landscape whose alignments of arcades and columns evoke the remains of antiquity, and acquire an aesthetic value. The façades of the Town Hall and the Ministry of Finance also lend themselves to this aestheticism. Photographers insist on the picturesqueness of these remains.[96] They ventured into destroyed buildings in search of the details that made the debris a ruin, as it was seen and defined in their time.[98] The commercial success of these collections of photographs can be explained by this dual objective: to document the results of the Commune fires, while at the same time casting a gaze that transfigures the rubble by transforming it into ruins and landscapes.[70]

- Photographs of the ruins of Paris published after Bloody Week

-

Paris City Hall. Photograph published in 1872.

-

Paris City Hall, inner courtyard. Photograph by Alphonse Liébert, 1871. Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris.

-

Ministry of Finance, rue de Rivoli.

-

Ministry of Finance, rue de Rivoli. Photograph published in 1871. Bibliothèque historique de la ville de Paris

-

Tuileries Palace. Photograph by Jean-Eugène Durand.

-

Attic of abundance. Photograph by Jean Andrieu. Paris Museums.

-

Corner of rue de Lille and rue du Bac. Photograph by Jean Andrieu. 1871, Carnavalet Museum, Paris

-

The Palais de la Légion d'Honneur, with the Palais d'Orsay in the background. Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

-

Palais d'Orsay. Photograph by Alphonse Liébert, 1871. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

Grande salle du Conseil d'État, in the Palais d'Orsay. Photograph by Charles Soulier, 1871. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

Page de titre d'un recueil de photographies publié en 1871. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The beauty and exoticism of Parisian ruins[edit]

The nineteenth century was a century of ruins: their poetics permeated contemporaries, who were particularly sensitive to them.[99] Monuments burnt down in 1871 were not immediately rebuilt. Ruins thus marked the Parisian landscape for years to come. They were seen with a romantic eye, and many emphasized their beauty.[88] As early as June 3, poet Malvina Blanchecotte noted in Tablettes d'une femme pendant la Commune:[100]

"City Hall. What a magnificent ruin! Dare I say it? I love ruins. These beautiful open windows, in the full sky, these splendid aerial arches where so many mysteries with so much unknown wind must like to pass the evening; these doors without rooms, fantastic; these dizzy staircases, insane, without reason to be, suspended in the life, without exit that space [...] were quite a dream."

Edmond de Goncourt enthusiastically described the colorful rubble of the Hôtel de Ville:[100][88]

"The ruin is magnificent, splendid. The ruin with its rose-colored tones, its ash-colored tones, its green tones, its white-reddened iron tones, the shining ruin of agatization, which the petroleum-baked stone has taken on, resembles the ruin of an Italian palace, colored by the sun of several centuries, or, better still, the ruin of a magical palace, bathed in an opera of electric gleams and reflections."

This parallel with the vestiges that wealthy tourists contemplate in Italy is widely used. Sir William Erskine, in a letter dated June 7, 1871, compares:[101]

"I've just seen the Paris City Hall in its ruins, lovingly caressed by a splendid setting sun; I've never imagined anything more beautiful; it's superb. The people of the Commune are awful scoundrels, I don't deny, but what artists! [...] I've seen the ruins of Amalfi bathed in the azure waves of the Mediterranean, the ruins of the temples of Tung-hoor in the Punjab; I've seen Rome and many other things: nothing can compare with what I've had before my eyes this evening.

Other archaeological remains are also evoked, such as Baalbek or Palmyra.[88] In another register, Louise Michel was also sensitive to the uncertain beauty of ruins:[100]

"The ruins of the fire of despair are marked with a strange seal. City Hall, from its empty windows like the eyes of the dead, watched for ten years as the revenge of the peoples came; the great peace of the world that we still await, it would still be watching if the ruin had been pulled down."

The Ministry of Finance regarded as an uninteresting recent building, has acquired an aesthetic value because its remains are reminiscent of ancient ruins. But it's the remains of the Hôtel de Ville that are most admired, for the picturesqueness of this jagged ensemble whose elements are in unstable equilibrium.[102] Joris-Karl Huysmans goes so far as to humorously suggest that monuments (the Bourse, the Madeleine, the Opéra, etc.) are burned to beautify them, because in his words: "Fire is the essential artist of our time ".[100] Nevertheless, descriptions of the ruins note the absence of vegetation, which makes Parisian ruins less beautiful than their ancient counterparts, while fire has created the illusion of an ancient vestige.[103] By artificially aging the buildings, fire creates an archaeological fiction.[104]

The indecency of this aestheticism is not lost on commentators such as Louis Énault, who confesses: "The artist killed the citizen in me, and I couldn't help saying to myself: 'It's terrible, but it's beautiful!".[103]

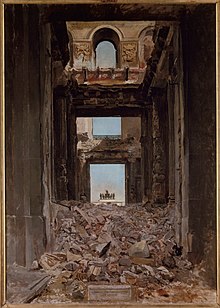

In a painting perhaps inspired by contemporary photographs and entitled Les Tuileries (May 1871), Ernest Meissonier brutally places the viewer at the heart of the ruin, in the Salle des Maréchaux in the center of the Tuileries.[105] In the foreground is a pile of rubble, the remains of the grand staircase.[106] The perspective shows the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, a reminder of the First Empire. This painting is a political critique of the Commune, which Meissonnier disliked. However, when Meissonnier completed the painting and exhibited it in 1883, the work took on a new meaning. It becomes a reminder of the ruins demolished in 1883, and an expression of nostalgia, reinforced by the Latin expression at the bottom of the painting, which links the Second Empire to Roman ruins:[105] Gloria Maiorum per flammas usque superstes, Maius MDCCCLXXI.[106]

The buildings burnt down in 1871 also fed the nostalgic imagination around the fictional ruins of the French capital, a literary genre that pre-existed the Commune.[107]

Rebuilding?[edit]

On May 27, 1871, while the fighting was still going on, Adolphe Thiers appointed Jean-Charles Alphand, who had worked with Prefect Haussmann, as Director of Works for Paris. Many architects who had worked under the Second Empire, some of whom built monuments that burned down, continued their careers under the nascent Third Republic: Théodore Ballu, Gabriel Davioud, Paul Abadie, Hector-Martin Lefuel... Within the space of a few years, the State and the City of Paris had regained the financial means to finance the work.[108] As early as June 1871, work began on repairing slightly damaged monuments and clearing away ruins.[109]

Half of the thirty or so public monuments more or less affected by the fire were of recent construction, dating from the Second Empire: these buildings were therefore not charged with history and symbolism, and for many, their disappearance was not considered a real loss, even by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.[110][16] Discussions took place on the future of these remains. Le Figaro receives letters calling for the Hôtel de Ville rubble to be retained.[111] Étienne Arago supports the same point of view, in the name of historical pedagogy:[112]

"The savage beauty of the burnt-out Hôtel de Ville, which I saw by day and by night, is perhaps second only to the striking effect of any other surviving fragment of an ancient monument. [...] By surrounding these dear, dark debris with a public garden, Paris would offer foreigners a marvelous historical curiosity, and, what is better, perpetuate a memory that would be a great lesson for its population."

But the need for administrative continuity prevailed.[111] The new Hôtel de Ville, rebuilt identically, was completed after ten years, in 1882.[39][113]

The remains of the Tuileries were leveled at the same time, in 1883 and 1884[114][88] after a debate oscillating between rebuilding the palace and conserving the remains.[115][111][116] Many projects were proposed, showing that the reborn Republic was reluctant to definitively destroy these emblematic remains of the Second Empire.[117] This work was preceded by the rapid reconstruction of the Hôtel de Salm, or Palais de la Légion d'honneur, financed by members of the national order of the Legion of Honor and completed in 1874.[118]

There was a certain degree of continuity between the Haussmannization of the Second Empire and the work carried out in Paris in the 1870s, which often completed projects begun before the war and the Commune,[119] except that the Third Republic built more utilitarian buildings linked to the industrial revolution than palaces.[16] Hélène Lewandowski believes that the fires "offered the new ruling class the opportunity to promote more sober, functional projects".[120] Thus, the remains of the Palais d'Orsay, where the Cour des Comptes was based, remained the longest-lived until they were purchased in 1897 by the Compagnie du Chemin de Fer de Paris à Orléans to build the Gare d'Orsay for the 1900 Universal Exhibition.[111][118]

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Caron, Jean-Claude (2006). Les feux de la discorde: Conflits et incendies dans la France du XIXe siècle (in French). Paris: Hachette Littératures. ISBN 978-2-01-235683-2. Archived from the original on 2023-12-01. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Fournier, Éric (2008). Paris en ruines: Du Paris haussmannien au Paris communard (in French). Paris: Imago. ISBN 978-2-84952-051-2.

- Jacquin, Emmanuel (1990). La direction des Beaux-Arts et les incendies de mai 1871. Bulletin de la Société de l'histoire de Paris et de l'Ile-de-France.

- Lewandowski, Hélène (2018). La face cachée de la Commune (in French). Paris: Éditions du Cerf. ISBN 978-2-204-12164-4.

- Lewandowski, Hélène (2021). "L'écran de fumée des incendies de la Commune de 1871". Cahiers d'histoire (148): 125–142. doi:10.4000/chrhc.15866. ISSN 1271-6669.

- Noël, Bernard (1978). Dictionnaire de la Commune (in French). Paris: Flammarion.

- Serman, William (1986). La Commune de Paris (1871) (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-01354-1.

- Thomas, Édith (1986). Les Pétroleuses (in French). Paris: Gallimard.

- Tillier, Bertrand (2004). La Commune de Paris, révolution sans image?: Politique et représentations dans la France républicaine, 1871-1914. Champ Vallon. doi:10.3917/sr.017.0373. ISBN 978-2-87673-390-9.

- Tombs, Robert (1997). La guerre contre Paris 1871 [Jean-Pierre]. Translated by Ricard. Paris: Aubier. ISBN 978-2-7007-0248-4.

References[edit]

- ^ Serman (1986, pp. 105–113)

- ^ Fournier (2008, pp. 39–53)

- ^ Caron (2006, pp. 105–109)

- ^ a b c d e Fournier (2008, pp. 55–64)

- ^ Corbin, Alain (1997), Mayeur, Jean-Marie (ed.), "Préface", La barricade, Histoire de la France aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French), Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, doi:10.4000/books.psorbonne.1147, ISBN 978-2-85944-851-6, retrieved 2024-03-11

- ^ Charles, David (1997), Corbin, Alain; Mayeur, Jean-Marie (eds.), "Le trognon et l'omnibus: faire "de sa misère sa barricade"", La barricade, Histoire de la France aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French), Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, pp. 137–149, ISBN 978-2-85944-851-6, retrieved 2024-03-11

- ^ Serman (1986, pp. 201–211)

- ^ Azéma, Jean-Pierre (1972). "Jeanne Gaillard, Communes de province, Commune de Paris 1870-1871". Annales. 27 (2): 503–504.

- ^ Tombs (1997, pp. 210–211)

- ^ Caron (2006, pp. 60–61)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Caron (2006, p. 63)

- ^ a b c d e f g Noël (1978, pp. 16–17)

- ^ a b c d e f Serman (1986, p. 502)

- ^ a b c d e Fournier (2008, pp. 98–102)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, p. 87)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lewandowski, Hélène (2021-03-01). "L'écran de fumée des incendies de la Commune de 1871". Cahiers d'histoire. Revue d'histoire critique (in French) (148): 125–142. doi:10.4000/chrhc.15866. ISSN 1271-6669.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Fournier (2008, pp. 90–92)

- ^ a b Lewandowski (2018, p. 66)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Serman (1986, p. 503)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Caron (2006, pp. 72–75)

- ^ a b c Tillier (2004, pp. 341–342)

- ^ a b c d "DARDELLE Alexis", Théodore, Alexis, dit Salvator (in French), Paris: Maitron/Editions de l'Atelier, 2021-08-17, retrieved 2024-03-11

- ^ a b texte, Société de l'histoire de Paris et de l'Île-de-France Auteur du (1990). "Bulletin de la Société de l'histoire de Paris et de l'Ile-de-France". Gallica. Retrieved 2024-03-11.

- ^ a b Boulant, Antoine (2016-06-02). Les Tuileries: Château des rois, palais des révolutions (in French). Tallandier. ISBN 979-10-210-1987-4.

- ^ "GOIS Émile, Charles, dit Degrin", Le Maitron (in French), Paris: Maitron/Editions de l'Atelier, 2022-10-22, retrieved 2024-03-11

- ^ Noël (1978, p. 316)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, p. 82)

- ^ Noël (1978, p. 160)

- ^ a b Noël (1978, p. 231)

- ^ a b Caron (2006, p. 62)

- ^ a b Lewandowski (2018, p. 67)

- ^ a b c Caron (2006, p. 64)

- ^ Noël (1978, p. 278)

- ^ a b c Fournier (2008, pp. 92–95)

- ^ a b c d Fournier (2008, pp. 111–130)

- ^ Tombs (1997, pp. 289–293)

- ^ Serman (1986, p. 508)

- ^ Serman (1986, p. 509)

- ^ a b c d e f Comité d'histoire de la Ville de Paris, ed. (2016). Notre-Dame et l'Hôtel de Ville: incarner Paris du Moyen âge à nos jours. Homme et société. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne Comité d'histoire de la Ville de Paris. ISBN 978-2-85944-921-6.

- ^ Caron (2006, p. 70)

- ^ Noël (1978, p. 74)

- ^ "BESLAY Charles, Victor", Le Maitron (in French), Paris: Maitron/Editions de l'Atelier, 2020-01-28, retrieved 2024-03-12

- ^ a b c d e Caron (2006, pp. 98–103.)

- ^ Bourgin, Georges (1938). "Comment les Archives nationales ont été sauvées en mai 1871". Bibliothèque de l'École des chartes. 99 (1): 425–427.

- ^ a b Noël (1978, p. 140)

- ^ a b c d e f Caron (2006, pp. 65–66)

- ^ a b c Fournier (2008, pp. 83–86)

- ^ a b Caron (2006, pp. 67–68.)

- ^ Tombs (1997, p. 254)

- ^ a b c Fournier (2008, pp. 95–98)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 110–111)

- ^ Caron (2006, pp. 76–79)

- ^ Gacon, Stéphane (2002). L'amnistie: de la Commune à la guerre d'Algérie. L'univers historique. Paris: Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-049368-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g Caron (2006, pp. 69–72)

- ^ a b Fournier (2008, pp. 259–267)

- ^ a b Lewandowski (2018, pp. 77–79)

- ^ Tombs (1997, p. 264)

- ^ Serman (1986, pp. 312–313)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 113–114)

- ^ Noël (1978, p. 7)

- ^ Noël (1978, p. 262)

- ^ a b Fournier (2008, pp. 102–105)

- ^ a b c Caron (2006, pp. 87–93)

- ^ a b c Fournier (2008, pp. 142–150)

- ^ Fournier (2008, pp. 150–152)

- ^ a b Fournier, Éric (2015-10-08). "Les temps de l'apocalypse parisienne de 1871". Écrire l'histoire. Histoire, Littérature, Esthétique (in French) (15): 159–166. doi:10.4000/elh.616. ISSN 1967-7499.

- ^ Deluermoz, Quentin (2020). Commune(s), 1870-1871: une traversée des mondes au XIXe siècle. L'univers historique. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-139372-9.

- ^ Fournier (2008, pp. 153–159)

- ^ Tombs (1997, p. 318)

- ^ a b Tillier (2004, pp. 350–356)

- ^ a b c Tillier (2004, pp. 335–340)

- ^ Perrot, Michelle; Rougerie, Jacques; Latta, Claude (2004-01-01). La commune de 1871: l'événement, les hommes et la mémoire : actes du colloque organisé à Précieux et à Montbrison, les 15 et 16 mars 2003 (in French). Université de Saint-Etienne. ISBN 978-2-86272-314-3.

- ^ "Les " Pétroleuses "". Folio (in French). 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Caron (2006, pp. 81–87)

- ^ Noël (1978, p. 156)

- ^ Bensaad, Anaïs (2014-10-16). "« La Représentation des Communardes dans le roman français de 1871 à 1900 », Master 1, sous la direction de Isabelle Tournier, Université Paris 8, 2013". Genre & Histoire (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ Dalotel, Alain (1997), Corbin, Alain; Mayeur, Jean-Marie (eds.), "La barricade des femmes", La barricade, Histoire de la France aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French), Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, pp. 341–355, doi:10.4000/books.psorbonne.1199, ISBN 978-2-85944-851-6, retrieved 2024-03-13

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 109–110)

- ^ Schapira, Marie Claude (1996), Régnier, Philippe; Rütten, Raimund; Jung, Ruth; Schneider, Gerhard (eds.), "La femme porte-drapeau dans l'iconographie de la Commune", La Caricature entre République et censure: L’imagerie satirique en France de 1830 à 1880: un discours de résistance?, Littérature & idéologies (in French), Lyon: Presses universitaires de Lyon, pp. 423–434, ISBN 978-2-7297-1051-4, retrieved 2024-03-13

- ^ a b Serman (1986, p. 504)

- ^ Charmasson, Thérèse (1984). "Christiane Demeulenaere-Douyère, Archives de Paris, Guide des sources de l'état civil parisien, Paris, Imprimerie municipale, 1982". Histoire de l'éducation. 21 (1): 140–141.

- ^ Ducoudray, Émile (1983). "Un guide des sources de l'état-civil parisien". Annales historiques de la Révolution française. 254 (1): 634–635. doi:10.3406/ahrf.1983.1080.

- ^ Cresson, Ernest (1824-1902) Auteur du texte (1901). Cent jours du siège à la préfecture de police: 2 novembre 1870-11 février 1871 / E. Cresson.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "L'Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux : Notes and queries français : questions et réponses, communications diverses à l'usage de tous, littérateurs et gens du monde, artistes, bibliophiles, archéologues, généalogistes, etc. / M. Carle de Rash, directeur..." Gallica. 1901-07-01. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ France, Cercle de la librairie (1871). "Bibliographie de la France : ou Journal général de l'imprimerie et de la librairie". Gallica. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ Tillier (2004, p. 42)

- ^ Fournier (2008, pp. 219–227)

- ^ a b c d e f g Caron (2006, pp. 93–98)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 116–118)

- ^ Fournier (2008, pp. 228–236)

- ^ Fournier (2008, pp. 241–247)

- ^ Lapostolle, Christine (1988). "Plus vrai que le vrai. Stratégie photographique et Commune de Paris". Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales. 73 (1): 67–76. doi:10.3406/arss.1988.2421.

- ^ Caron, Jean-Claude; Aprile, Sylvie, eds. (2014). Paris, l'insurrection capitale. Époques. Seyssel: Champ Vallon. ISBN 978-2-87673-997-0.

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, p. 108)

- ^ a b Fournier, Eric (2018-11-07). "La Commune de 1871: un sphinx face à ses images". Sociétés & Représentations (in French). 46 (2): 245–257. doi:10.3917/sr.046.0245. ISSN 1262-2966.

- ^ a b Fournier (2008, pp. 196–202)

- ^ Lavaud, Martine (2008), Mollier, Jean-Yves; Régnier, Philippe; Vaillant, Alain (eds.), "Industrie photographique et "production" littéraire pendant la Commune de Paris", La production de l’immatériel: Théories, représentations et pratiques de la culture au xixe siècle, Le XIXe siècle en représentation(s) (in French), Saint-Étienne: Presses universitaires de Saint-Étienne, pp. 377–390, ISBN 978-2-86272-757-8, retrieved 2024-03-13

- ^ Fournier, Éric (2006-06-01). "Les photographies des ruines de Paris en 1871 ou les faux-semblants de l'image". Revue d'histoire du XIXe siècle. Société d'histoire de la révolution de 1848 et des révolutions du XIXe siècle (in French) (32): 137–151. doi:10.4000/rh19.1101. ISSN 1265-1354.

- ^ Fournier (2008, pp. 167–190)

- ^ a b c d Tillier (2004, pp. 344–347)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, p. 120)

- ^ Fournier (2008, pp. 210–213)

- ^ a b Fournier (2008, pp. 202–210)

- ^ Tillier (2004, pp. 348–350)

- ^ a b Tillier (2004, pp. 357–360)

- ^ a b "Ruines du palais des Tuileries - 1871 - Histoire analysée en images et œuvres d'art". L'histoire par l'image (in French). Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ^ Roussier, Marianne (2019-03-09). "Le Voyage aux Ruines de Paris : un topos érudit, fantaisiste et satirique dans la fiction d'anticipation aux XIXème et XXème siècles". Belphégor. Littérature populaire et culture médiatique (in French) (17). doi:10.4000/belphegor.1953. ISSN 1499-7185.

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 143–150)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 152–153)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 137–143)

- ^ a b c d Fournier (2008, pp. 248–257)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 151–152)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 159–166)

- ^ Tillier (2004, pp. 360–362)

- ^ Boulant, Antoine (2016-06-02). Les Tuileries: Château des rois, Palais des révolutions (in French). Tallandier. ISBN 979-10-210-1987-4.

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 166–174)

- ^ Lemire, Vincent; Potin, Yann (2011-12-10). "Reconstruire le Palais des Tuileries. Une émotion patrimoniale et politique « rémanente » ? (1871-2011)". Livraisons de l'histoire de l'architecture (in French) (22): 87–108. doi:10.4000/lha.293. ISSN 1627-4970.

- ^ a b Lewandowski (2018, pp. 156–159)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 175–182)

- ^ Lewandowski (2018, pp. 190, 194–195)