Fort Delaware

39°35′24″N 75°34′19″W / 39.59000°N 75.57194°W

| Fort Delaware | |

|---|---|

| Part of American Civil War prison camps 1861–1865 Harbor Defenses of the Delaware 1898–1945 | |

| Fort Delaware, Pea Patch Island, New Castle County, Delaware, United States | |

Fort Delaware during the American Civil War | |

| Type | Garrison Fort, Training Camp, Union Prison Camp |

| Site information | |

| Owner | U.S. Government |

| Controlled by | Union Army |

| Open to the public | Yes |

Fort Delaware | |

Fort Delaware on Pea Patch Island | |

| Location | Fort Delaware State Park, Pea Patch Island, New Castle County, Delaware, USA |

| Nearest city | Delaware City, Delaware |

| Area | 288 acres |

| Built | 1846-1868[2] |

| Architect | Joseph G. Totten |

| Architectural style | Third System |

| NRHP reference No. | 71000226[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 16, 1971 |

| Site history | |

| In use | 1846–1945 |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War World War I World War II |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | U.S. Army soldiers, Confederate prisoners of war |

Fort Delaware is a former harbor defense facility, designed by chief engineer Joseph Gilbert Totten and located on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River.[3] During the American Civil War, the Union used Fort Delaware as a prison for Confederate prisoners of war, political prisoners, federal convicts, and privateer officers. A three-gun concrete battery of 12-inch guns, later named Battery Torbert, was designed by Maj. Charles W. Raymond and built inside the fort in the 1890s. By 1900, the fort was part of a three fort concept, the first forts of the Coast Defenses of the Delaware, working closely with Fort Mott in Pennsville, New Jersey, and Fort DuPont in Delaware City, Delaware. The fort and the island currently belong to the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) and encompass a living history museum, located in Fort Delaware State Park.

Background

In 1794, the French military engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant was surveying for defensive sites. He identified an island that he called "Pip Ash" as an ideal site for the defense of the prize of American commerce and culture.[3][4] The island that L'Enfant called Pip Ash was locally known as Pea Patch Island. This island was mostly unaffected by humanity with one exception. Dr. Henry Gale, a New Jersey resident, used Pea Patch as a private hunting ground.[3] Gale was offered $30,000 for the island by the US Army, but he refused. The military was determined to get the island, so they appealed to the state of Delaware, which claimed ownership of the entire Delaware River and all islands therein within a twelve mile circle around New Castle's Court House. The state legislature passed an act in May 1813 ceding the island to the United States government, which subsequently seized it from Gale. In 1820, seeking to resolve questions surrounding the ownership of the island, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun requested a legal opinion from Attorney General William Wirt. Wirt's conclusion, based on a report by George Read, Jr. and former Attorney General Caesar A. Rodney was that the state of Delaware had the valid claim to the island, and so New Jersey could not have properly deeded it to Gale.[5]

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, efforts were made to fortify Pea Patch Island. This plan of defense was largely coordinated by Capt. Samuel Babcock, who was working nearby on similar defenses in Philadelphia. During this time a seawall and dykes were built around the island. There is no known evidence that any progress was made on the actual fortification by war's end. The original plan was to build a Martello tower on the island.[2] One source states that an earthwork fort was built on the island during the war and torn down in 1821; also, a wooden fort existed from 1814 to 1824.[6]

Star fort

Construction of a star fort on Pea Patch island began sometime before December 8, 1817. Chief Engineer Joseph Gardner Swift mentions a fort on the "Pea Patch in Delaware River" among forts that are progressing nicely.[7]

Fort Mifflin's replacement

The attack on Fort Mifflin during the Revolutionary War proved that a fort was needed further away from Philadelphia in order to delay possible invaders. A fortification further downriver would also provide protection for other vital port cities such as Chester, Marcus Hook, Wilmington, and New Castle. On February 7, 1821, the Board of Engineers reported: "In the Delaware, the fort on the Pea Patch island, and one on the Delaware shore opposite, defend the water passage as far below Philadelphia as localities will permit: They force an enemy to land forty miles below the city to attack it by land, and thus afford time for the arrival of succors [...] The two projected forts will also have the advantages of covering the canal destined to connect the Chesapeake with the Delaware[.]"[8] The fort on the Delaware shore was not built until the Civil War.

Construction issues

The star fort was designed by army engineer Joseph G. Totten and construction was supervised by Capt. Samuel Babcock.[9] The five-pointed star design is viewed as "transitional" between the second and third systems of US fortifications. The fort was designed in 1815 and construction began within a few years.[10] Babcock supervised the work from about August 1819 until August 20, 1824.[11] Lt. Henry Brewerton was also on site, serving as an assistant engineer during the construction. Completion of the project was delayed years past the proposed date due to uneven settling, improper pile placement and the island's marshy nature. In one occurrence an entire section of 43,000 bricks had to be taken down, cleaned, and reworked due to massive cracking. In 1822, Colonel Totten and General Simon Bernard were on the island to inspect the faulty works. Captain Babcock was severely criticized for altering Totten's plans without orders. Babcock subsequently appeared before a court-martial for his actions in late 1824. It was determined he was not guilty of neglect but rather error in judgement and he was acquitted. During the trial his counsel was George Read Jr. of New Castle, Del.[11]

Commanders and garrison

Fort Delaware's first documented commander was Maj. Alexander C.W. Fanning, who took command prior to 1825. That year, a letter documenting a lost mail shipment was written by him as post commander. Army records document that the fort was manned by soldiers of the 2nd U.S. Artillery. Circa 1829, Major Benjamin Kendrick Pierce took command of Fort Delaware. During his tenure, the fort was garrisoned by Companies A and B, 4th U.S. Artillery. Major Pierce was the older brother of the 14th President of the United States, Franklin Pierce.

1831 fire

In February 1831, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers sent Lt. Stephen Tuttle to evaluate the foundation issue and offer possible solutions. On February 8, 1831, around 10:30 p.m, a fire originating in Lieutenant Tuttle's quarters[12] destroyed much of the work, burning until the next morning. Maj. Pierce, the post commander, was granted orders to use the federal arsenal in New Castle, Del. as barracks for his two companies until "Fort Delaware can be reoccupied." Captain Richard Delafield, Babcock's replacement, asked for $10,000 to tear down the remaining structure the following year. In 1833, Fort Delaware was torn down to make room for a new fortification. According to official records, the rubble from the star fort served to reinforce the seawall around the island. The sandstone remnants can still be seen today.

Polygonal Fort

Captain Delafield designed the second version of Fort Delaware "as a huge bastioned polygonal form to be built in masonry."[13] Delafield desired his fort to be "a marvel of military architecture on Pea Patch", and the design was much larger than the star fort.[10] In 1836, excavation work progressed on the north side of the island. Grillage timbers were driven into the island's soft mud to serve as a base for the foundation of Delafield's fort. In 1838, James Humphrey of New Jersey (a descendant of Dr. Henry Gale) sent legal representation to the island, claiming he had legal rights to the island.[14] This began a decade-long legal battle over the island's ownership, which prevented Delafield's fort from being built. After conflicting opinions from two different circuit courts, President James K. Polk suggested an arbitrator resolve the disagreement, and Secretary of War William Marcy and Humphrey agreed. John Sergeant was appointed arbitrator, and in late 1847 heard arguments from the United States (represented by Senators John M. Clayton and James A. Bayard Jr.) and Humphrey (represented by former Secretary of War John Eaton and former Secretary of the Treasury George M. Bibb). On January 15, 1848, he ruled that the island had belonged to the state of Delaware and therefore the title given to the United States government was valid.[15] It appears no further work was done on this fort.[16]

Pentagonal fort

The present Fort Delaware was erected mainly between 1848 and 1860 as one of the larger forts of the third system of US fortifications. Although major construction was wrapped up before the Civil War, the post engineer did not declare the fort finished until 1868.[17] Construction of the counterscarp wall, slate pavement, and "hanging shutters and doors" was still ongoing.[18][19] The fort was designed by Army chief engineer Joseph G. Totten, and construction was supervised by Major John Sanders. Engineers in supporting roles included Captain George B. McClellan, Major John Newton, Lieutenant William Price Craighill, Lieutenant Montgomery C. Meigs and civilian engineer Edwin Muhlenbrach.[20] The fort was about the size and location of the previous star fort. It was in the shape of an irregular pentagon, with five small bastions at the corners, called "tower bastions" by Totten. Four of the sides were seacoast fronts, with three tiers of cannon on each, two casemated tiers in the fort and one barbette tier on the roof. The irregular shape provided for more cannon on the east-facing fronts, where the deeper channel was. A total of 123 heavy cannon could be mounted on the seacoast fronts, with 15 more in the bastions. The long rear front was called a "gorge wall", with two tiers totaling 68 loopholes for muskets and a tier of 11 cannon on the roof. In the center of this wall was the sally port, the only entrance to or exit from the fort. Twenty short-range flank howitzers could be mounted in the bastions to defeat attacks on the curtain walls. Thus, the fort had positions for 169 cannon. The fort also had a moat, with a tide gate on a canal from the river to control the moat's level.[10]

Foundation

Construction of a deep foundation was necessary since the island's soils were of "a compressible mud often forty feet deep; the level where sand was finally reached".[21] In 1849, Sanders' crews began using steam-powered pile drivers to place long piles (similar to modern telephone poles) in excavated areas to provide adequate support. In 1850 pile driving was complete; crews had driven 4,911 piles, reusing 1,095 piles from the Delafield fort.[22] Because of the star fort's failed foundation, Totten and Sanders decided to evaluate the weight resistance before moving forward with construction. The engineers proposed a singular test consisting of 30 blows from an 8-foot height using an 800 pound weight. A total of 5,754 piles were tested and 2,955 failed more than one fifth of an inch. Roughly 1,700 piles were subsequently spliced and re-driven an additional 10 to 20 feet. The pile driving was finally complete in 1851 and the wooden grillage was the next layer constructed.[21]

Stonework

The fort is primarily composed of gneiss, granite, brick, and cement. Initially, the stone for the scarp wall was gneiss imported from Port Deposit, Maryland.[23] In 1852, Major Sanders reported the gneiss was too hard for his stone masons and cutters to shape, slowing the progress of construction. After that, purchase records show granite was bought from John Leiper's quarry in nearby Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Leiper's granite was also used throughout for various items such as the steps for the circular stairways. Stone from Vinalhaven, Maine was used for the stairways' large platforms.[24] A huge storm damaged the island's dyke and seawall in 1854. Due to the threat of high-tide waters, efforts were directed toward repairing the dyke and adjacent seawall, slowing progress on the stonework.[23]

Brickwork

More than two million bricks were purchased from Wilmington, Del. and Philadelphia, Pa. for the scarp wall's interior. These bricks were used in construction of underground cisterns, casemates, powder magazines, soldier barracks, officer quarters, bread ovens and the fort's breast high wall. Masonry arches and vaults were used throughout the entire fort to equally distribute weight and to provide stability. Poured concrete was used as a layer above the vaults to offer counter resistance and to "create a strong floor system".[25]

Major Sanders dies

On July 29, 1858, Major Sanders died on the island due to "complications of carbunculous boils"; Lt. William Craighill replaced him until Maj. John Newton was able to assume the role of supervising engineer.[26] In 1859, in official correspondence, Major Newton reported that the fort would be ready to arm and garrison by 1860.[25] In 1861, before the war started, Capt. Augustus A. Gibson took command of the fort and a small garrison of only 20 regular army soldiers. Construction languished until the end of the Civil War; the garrison's focus was centered on mounting cannon inside the fort. In 1861, 20 columbiad guns were received and work to mount these guns quickly began. By 1862, another 17 guns were delivered. By 1866, approximately 156 guns were mounted in total, filling the fort's casemates and ramparts to capacity.

Civil War

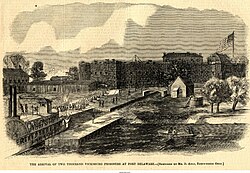

During the Civil War, Fort Delaware went from protector to prison; a prisoner-of-war camp was established to house captured Confederates, convicted federal soldiers, and local political prisoners as well as privateers.[27] The first prisoners were housed inside the fort in sealed off casemates, empty powder magazines, and two small rooms inside the sally port. In those small rooms, names of Confederates can still be seen carved into the brick. According to The Philadelphia Inquirer, the island "contained an average population of southern tourists, who came at the urgent invitation of Mr. Lincoln". The first Confederate general to be housed at the fort was Brig. Gen. Johnston Pettigrew. During the war, a total of about a dozen generals were held within the fort as prisoners of war.

Barracks & hospital

In 1862 and 1863, two separate phases of construction took place, building a "barracks for enlisted prisoners of war" that was known as the "bull pen," said Pvt. Henry Robinson Berkeley a Confederate prisoner.[28] Most of the Confederates captured at Gettysburg were imprisoned here.[3] An L-shaped barracks building, using similar plans, was constructed for Union soldiers assigned as guards. A 600-bed hospital was also built around the same time and was designed by architect John McArthur Jr. of Philadelphia. "These Barracks [sic] were common wooden sheds, affording accommodation for about ten thousand persons," wrote Lt. Francis W. Dawson, a Confederate POW captured in August 1862. "The bunks were arranged in tiers of three, and into one of these I crawled. The next morning I was told that these Barracks were the quarters for the privates and non-commissioned officers, and that, by requesting it, I could be removed to the quarters for the officers, which were inside the Fort."[29]

Mortality rate

The first Confederate prisoner to die at Fort Delaware was Captain L. P. Halloway of the 27th Virginia Infantry. He was captured at Winchester, Va. on March 23, 1862, dying on April 9.[30] Captain Halloway, a Freemason, was given a full Masonic funeral by Jackson Lodge in Delaware City. The funeral procession was led by fort's commander, Captain Augustus A. Gibson, from the town's lock on Clinton Street, and ended in the cemetery on Jefferson Street. According to church records, Halloway's body was reclaimed by his family after the war.

By August 1863, there were more than 11,000 prisoners on the island; by war’s end, it had held almost 33,000 men. The conditions were relatively decent, but about 2,500 prisoners died on Pea Patch Island.[31][32] Statistically, the overall death rate for prisoners was about 7.6 percent. Half of the total number of deaths occurred during a smallpox epidemic in 1863. Inflammation of the lungs (243 deaths), various forms of diarrhea (315 deaths) and smallpox (272 deaths) were the leading killers amongst the prison population.[33][34] About 215 prisoners died as a result of typhoid and/or malaria, according to records in the National Archives. Other causes of death include scurvy (70 deaths), pneumonia (61 deaths) and erysipelas (47 deaths). Five prisoners drowned, and seven died from gunshot wounds.[34] During the war, 109 Union soldiers and about 40 civilians died on the island as well.[35]

Many of the Confederate prisoners and Union guards who died at the fort are buried in the nearby Finn's Point National Cemetery in Pennsville, New Jersey.[36]

Prisoner rations and living conditions (outside the fort)

By 1863, enlisted men and junior officers (mostly lieutenants and captains) of the prison population were living in the wooden barracks on the northwest side of the island. These two classes of prisoners were separated by a tall fence complete with a catwalk for the guards. In 1864, the War Department ordered the rations to be cut in retaliation for the treatment of Northern soldiers in southern POW camps. Although prisoners were only receiving two small meals, they were allowed to purchase extra food from the sutler, and allowed to fish in the waterways on the island and in the Delaware River.[37] Official records also show that prisoners at Fort Delaware received more "care packages" than any other POW camp in the country.

"Things here are not quite as bad as I expected to find them. They are, however, bad, hopeless and gloomy enough without any exaggeration," said Pvt. Henry Berkeley. "We went into dinner about three o'clock, which consisted of three hardtack, a small piece of meat (about three bites) and a pint tin cup of bean soup. We only get two light meals a day."[38]

"The mess-room is next to [Division] 22 and near the rear. It is a long, dark room, having a long pine table, on which the food is placed in separate piles, either on a tin plate or on the uncovered greasy table, at meal hours, twice a day," said Capt. Robert E. Park, 12th Alabama Infantry Regiment. "The fare consists of a slice of baker's bread, very often stale, with weak coffee, for breakfast, and a slice of bread and a piece of salt pork or salt beef, sometimes, alternating with boiled fresh beef and bean soup, for dinner. The beef is often tough and hard to masticate."[39]

"There are several large ditches running across the island which are filled daily by the bay water and which furnish the water for washing," wrote Capt. William H. Burgwyn, 35th North Carolina Infantry. "Our drinking water is brought from Brandywine Creek about ten miles [away]."[40]

Prisoner rations and living conditions (inside the fort)

High-ranking Confederate officers and some political prisoners were housed in former laundress quarters and open-bay barrack rooms inside the fort.[41][42] These prisoners were often afforded paroles of the island, access to more food, and allowed more freedoms than the outside prison population.

"By the kindness of Gen. Albin Francisco Schoepf (the fort's commandant), Cols. Morgan, Tucker, Coleman and myself were paroled to the Island", said Col. William W. Ward, on March 24, 1864. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson, Gen. Robert B. Vance and the Cols of our command form a mess, and live very well. We give a negro woman $7.00 per week for cooking, $10.00 for washing."[43]

Also living in the former laundress quarters was Reverend Isaac W. K. Handy of Portsmouth, Va., a political prisoner. "Our supplies have, recently, been so abundant, that "Commissary" Tibbetts has appropriated [Room] No. 3 as a larder and pantry. We have been living upon hams, turkeys, chickens, tongues, jellies, pickles, butter, cheese, canned fruits, and jellies of various kinds, with all else that could be desired for comfortable and healthy diet," wrote Reverend Handy in 1864. He further notes, "The only article regularly furnished by the Government commissary is bread. Each man gets a well baked loaf, every other day, which is quite sufficient in quantity."[44]

"We were installed in a large barrack-room, which then contained seventy or eighty officers. The highest in rank was a Major Holliday," wrote Lt. Francis W. Dawson. "Our room was dry, warm and well lighted, while the Barracks [outside of the fort] were cold, damp and dark. Our room had conveniences for washing [...], and there was plenty of water of a poor quality," said Dawson. "We only left the room to march down into the mess-hall."[45]

In late 1862, prisoners inside the fort were fed three meals a day instead of the usual two. "For breakfast we had a cup of poor coffee without milk or sugar, and two small pieces of bad bread. For dinner we had a cup of greasy water misnamed soup, a piece of beef two inches square and a half inch thick, and two slices of bread. At supper the fare was the same as at breakfast. This was exceedingly light diet," wrote Lt. Francis Dawson. "We contrived to make some additions to our diet by purchases at the Sutler's store."[46]

The "Immortal 600"

On August 20, 1864, six hundred Confederate officers boarded the Crescent bound for Morris Island, S.C., "for the purpose I believe of being placed under the fire of the Confederate batteries in retaliation for an equal number of Federal officers who have been placed in the city of Charleston, and are said to be exposed to the shelling of their own guns. I am glad of this move as it will be a diversion to the monotonous life led in prison," said Capt. Leon Jastremski of the 10th Louisiana Infantry. This group of prisoners was later known as the "Immortal Six Hundred".[47]

"Aug. 20 - Am detailed to go to Charleston with the Rebel Officers. Was very busy in the forenoon hunting up shoes and packing up things," said Pvt. Alexander J. Hamilton, Pittsburgh Heavy Artillery. "At 3 p.m. we fell in and marched up to the barracks and by 5 were on board the Crescent and under way. There are 35 of our boys and about 90 of the other two batteries and of Company C, 157th Ohio [Infantry]."[48]

"After long delay - all being ready - the guards took their places, and the command was given to march through the sally-port, to the west end of the "bull-pen"," according to Reverend Isaac Handy. "As the noble fellows marched out, I stood at the opening of the sally-port, as near by as the guards would allow, and until the very last man disappeared from the enclosure. 'Good-bye! Good-bye!' was uttered, time and again, as the files moved on; and I could do nothing but return farewells, as some one or more in every rank would wave the parting salutation."[49]

Garrison units

Starting in 1861, volunteer troops were sent to garrison Fort Delaware that included Collis' Zouaves d' Afrique,[50] the 19th New York Volunteers, Mlotkowski's Independent Battery A,[51] Young's Independent Battery G (Pittsburgh Heavy Artillery), 5th Delaware Infantry, 6th Delaware Infantry, 9th Delaware Infantry, 5th Maryland Infantry, 11th Maryland Infantry, 6th Massachusetts Militia, 157th Pennsylvania Infantry (Battalion), 201st Pennsylvania Infantry, 215th Pennsylvania, 157th Ohio Infantry, 196th Ohio Infantry, and Zouaves of the 165th New York Infantry.[52] The fort was also used to organize and muster troops from Delaware. Ahl's Independent Battery of Heavy Artillery was organized at the fort on July 27, 1863 for garrison duty.[53] Although listed as a Delaware unit, Ahl's Battery was composed of Confederate prisoners that took the oath of allegiance. The fort's artillery soldiers were responsible for manning the guard posts within the fort as well as serving on various duty positions on the island. Infantry troops were mainly responsible for manning guard posts along the seawall, which ran around the island. In August 1864, there were approximately 85 guard posts on the island that required about 255 men on each shift.[54]

1870s and 1880s

After the Civil War, the fort was operated by a small garrison of the 4th U.S. Artillery. In the early 1870s, plans were made to modify the five bastions to support 15-inch Rodman guns. During the Civil War a ten-gun battery was built on the river's west bank near the later Fort DuPont; this was rebuilt as a 20-gun battery in the 1870s but not fully armed.[55]

In October 1878, a massive hurricane struck the area causing considerable damage to structures outside the fort. The majority of buildings on the south side of the island were destroyed. The Trinity Chapel, built in 1863 by Confederate POWs, was partially destroyed in the storm. The chapel was subsequently used to store hay until totally demolished sometime after 1901.

On August 3, 1885, a tornado struck the island, destroying the post-war hospital and caused considerable damage to other structures. "A storm took place here. We have had nothing like it since [October 1878] and a strong whirlwind with it, sweeping every thing before it, pulling trees out of the ground and carrying parts of the hospital all over the island and out on the river," wrote Ordnance Sergeant James Maxwell.[56]

Spanish–American War

Several years before the start of the war, in 1892, a mine control casemate was built on the northern tip of the island. This casemate was built semi-underground and then covered with dirt for concealment. This mining casemate served in conjunction with a one-story torpedo (mine storage) shed and a narrow-gauge railroad, which all supported water-tight mines that could be placed in the Delaware River as a defensive measure against a possible enemy attack. Another casemate at Fort DuPont was built for a mine field controlled by that fort. A similar mine casemate at Fort Delaware had been planned in the 1870s but never materialized due to lack of funding.

Modernization during the Endicott period

During the late 1890s new gun batteries were constructed at Fort Delaware. These batteries were part of a program initiated by the 1885 Board of Fortifications, a government board headed by Secretary of War William C. Endicott; the resulting system of fortifications is often called the Endicott program. Instead of many guns concentrated in a traditional thick-walled masonry structure, the Endicott batteries are spread out over a wide area, concealed behind concrete parapets flush with the surrounding terrain. As part of this program, Fort Delaware was supplemented by Fort DuPont on the river's west bank and Fort Mott on the east bank; these were the first forts of the Coast Defenses of the Delaware. Both of these were built new for the Endicott program, in both cases replacing earlier batteries. Part of an unfinished battery at Fort Mott from the 1870s was used for new batteries at that fort.[57][58]

In 1896, half of the soldier barracks and a set of officers' quarters were demolished inside the fort.[3] The parade ground was excavated and thousands of piles were steam driven, to support a foundation for a concrete three-gun battery as a way to modernize the defenses protecting ports along the Delaware River. Construction halted for a brief period before resuming in August 1897. This main battery was designed by Army engineer Lt. Col. Charles W. Raymond, assisted by Lt. Spencer Cosby. The new Endicott structure was a three-story reinforced concrete emplacement, which was built from 1894 to 1900 to support three 12-inch breech-loading rifled guns on disappearing carriages. These guns, mounted in 1900, had a range of approximately 10 miles.[59] The three-gun battery, later named Battery Torbert after Maj. Gen. Alfred Torbert, is one of two three-story Endicott batteries in the United States, the other being Battery Potter, with unique gun-lift carriages, at Fort Hancock, New Jersey.[60][61][62] The unusual height of Battery Torbert was due to being initially designed for gun-lift carriages. On top of the fort, flanking the 12-inch battery, were two smaller rapid-fire batteries, which protected the short-range sectors around the island and the mine field. These positions were later named Battery Allen and Battery Alburtis, and were armed with two 3-inch M1898 guns on retractable masking parapet mounts each. They were built in 1899 and accepted for service in 1901. Outside of the fort, engineers built additional rapid-fire batteries, which were later named Battery Dodd and Battery Hentig. Battery Dodd was added as an emergency measure after the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in 1898. It had two 4.7-inch 40 caliber guns purchased from the United Kingdom; at that point few of the Endicott batteries were complete and it was feared the Spanish fleet would bombard the US east coast. The battery was completed in 1899, after the war was over. Battery Hentig had two 3-inch M1903 guns and entered service in 1901.[57][58][62]

Battery Allen was named for Robert Allen, Jr., a cavalry officer who died at Gaines Mill in the Civil War. Battery Alburtis was named for William Alburtis, killed in the siege of Veracruz in the Mexican–American War. Battery Dodd was named for Captain Albert Dodd, also killed at Gaines Mill. Battery Hentig was named for Edmund C. Hentig, a cavalry officer killed fighting Native Americans at Cibiou Creek, Arizona in 1881.[62]

Garrison units

During the Spanish–American War, the fort was garrisoned by artillery soldiers of the 4th U.S. Artillery and volunteers from Company I of the 14th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Names of soldiers from the 14th P.V.I. appear today, carved on the brick walls inside the fort. These soldiers were stationed on the island during the summer of 1898.

World War I

Following a period of caretaking status, the fort was garrisoned for a brief time during World War I. Nearby Fort DuPont was the main defense site, with Fort Delaware and Fort Mott serving as a sub-posts, according to army records.[63] In March 1919, soldiers began the process of mothballing the old fort, removing everything except items pertaining to the three 12-inch guns of Battery Torbert, according to Pvt. James C. Davis, a Fort DuPont soldier who worked on the detail. In a Newark Post article, he recalls his orders were to bury everything with explicit orders not to throw anything in the river or remove articles from the island. According to Davis, soldiers buried three pieces of artillery on the island. Only one gun has since been recovered; a 15-inch Rodman gun exhumed from the northwest bastion was sold for scrap during World War II. The 4.7-inch guns of Battery Dodd were sent to San Francisco for use on Army troop transports; they were returned to Fort Delaware in 1919 but were soon removed from service and used as war memorials.[62] In 1920 the 3-inch guns of Battery Alburtis and Battery Allen were scrapped as part of a general removal of M1898 3-inch guns from service. By the end of the First World War, Fort Saulsbury near Slaughter Beach, Del. was near completion, and with 12-inch guns on long-range carriages reduced the three upriver forts to secondary lines of defense. The Harbor Defenses of the Delaware were one of the most extreme examples of gun batteries being built seaward as gun ranges increased.[58][64]

World War II

In 1940 Fort Delaware lost its three 12-inch guns, two of which were used to arm Battery Reed, Fort Amezquita in the Harbor Defenses of San Juan, Puerto Rico.[62][65] Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the island was garrisoned by a detachment of soldiers from Battery C, 261st Coast Artillery Battalion, a unit from the Delaware Army National Guard. Battery C manned the two rapid-fire guns of Battery Hentig, located outside of the fort. These guns were removed in 1942 for use at Fort Miles in Lewes, Del., leaving Fort Delaware unarmed. Fort Miles, on the Atlantic Ocean south of Cape May, itself reduced Fort Saulsbury to a secondary line of defense.[57] The fort was eventually stripped of the most of its electrical wiring, which was re-used at Fort Miles. Fort Delaware was declared as a surplus site by the federal government at the end of the war.

The fort today

Delaware acquired the fort from the United States government in 1947 after the federal government declared it a surplus site. Today, Fort Delaware State Park encompasses all of Pea Patch Island, including the Fort. As of 2018, transportation to Fort Delaware from Delaware City and Fort Mott is provided by a seasonal passenger ferry, the Forts Ferry Crossing.[66] Once at the island, visitors are brought to the fort on a jitney. Tours and special programs are available to visitors. For example, visitors may see the 8 inch Columbiad gun, which is located on the northwest bastion, fired daily. Park staff and volunteers interpret the roles of people who were at the fort during the Civil War.

Beach erosion affecting Pea Patch Island was recognized as a potential threat to the Fort in 1999. The United States Army Corps of Engineers erected a 3,500-foot-long seawall during the Winter of 2005-2006 which now protects the historical fort site and a migratory bird rookery, considered to be the largest such habitat north of Florida.

Popular events

Starting in 2009, Fort Delaware has hosted at least one game each summer of the Diamond State Base Ball Club, a vintage base ball team. The Diamond State Base Ball Club also typically plays 4-6 games per year at nearby Fort DuPont. The Diamond State Base Ball Club is a non-profit amateur organization created for the purposes of providing physical fitness to its members, educating the public on the history of baseball and local history, and serving as a point of public pride.

Television & pop culture

The A&E Network's Civil War Journal recorded portions of an episode at the fort entitled "War Crimes: The Death Camps" that originally aired October 9, 1994.

The Sci-Fi Channel investigation series Ghost Hunters conducted two cases there including a live televised investigation on Halloween in 2008.

The Sci Fi Channel investigation series Ghost Hunters Academy recorded an episode, which aired June 23, 2010.

The British series Most Haunted also did an investigation of the fort in their 11th series of the show.

See also

- Seacoast defense in the United States

- Harbor Defense Command

- United States Army Coast Artillery Corps

- List of coastal fortifications of the United States

Galleries

Buildings and grounds

-

Photo of barracks inside Fort Delaware taken circa 1910. Army Quartermaster Department Photo.

-

U.S. Army photograph facing the sally port in 2011.

-

8-inch Columbiad gun manufactured by Cyrus Alger & Co., in 1855.

-

Mine storehouse built in 1897.

-

Mine storehouse built in 1897.

-

Bird's eye view of Fort Delaware taken in 2010. Photograph by Missy Lee.

-

View from Battery Torbert showing wooden stairway cap and brick officers' quarters.

-

Courtyard.

-

Courtyard with cannon balls.

-

Doorways.

-

Courtyard and reenactor.

-

Courtyard and reenactor.

Interiors

-

Original 32-pounder gun on reproduction carriage in Casemate 29.

-

Fort Delaware kitchen with reenactor.

-

Fort Delaware kitchen.

-

Wash tubs and reenactor.

-

Pitcher and basin.

-

Reproduction flush toilets inside privy at Fort Delaware.

Other

-

Chesapeake & Delaware Canal map (Circa 1829).

-

Amanda Boykin Pierce's marker in New Castle, Del. She died in Fort Delaware on January 17, 1831. Photograph by Brendan Mackie.

-

Confederate POW cover with North and South postage stamps.

-

Brig. Gen. M. Jeff Thompson photographed while a prisoner at Fort Delaware in 1864. Photograph by John L. Gihon

-

Construction of Battery Dodd in 1898. Photograph by Frank C. Warner, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

-

Star spangled banner.

References

This article has an unclear citation style. (January 2019) |

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Dobbs, Kelli W.; Siders, Rebecca J. Fort Delaware Architectural Research Project. Newark, DE: University of Delaware, Center for Historic Architecture and Design, 1999.

- ^ a b c d e Dobbs, Kelli W., et al.

- ^ "Fort Delaware - History". Fort Delaware official web site. State of Delaware. December 11, 2002. Archived from the original on September 15, 2006. Retrieved September 13, 2008.

- ^ United States Congress (1860). "American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, Volume 33". Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States. New York: Macmillan. pp. 129–130. ISBN 0-02-926880-X.

- ^ The Papers of John C. Calhoun, Letter from Brig. Gen. Joseph Gardner Swift, Chief Engineer to John C. Calhoun. Dec 8, 1817. Vol II, page 4.

- ^ Mackie, Brendan., Peter K. Morrill, Laura M. Lee. Images of America: Fort DuPont. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2011., p 14.

- ^ Dobbs, Kelli. et al, 1999: p.7

- ^ a b c Weaver 2018, pp. 171–176.

- ^ a b American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, From the First Session to the Second Session of the Eighteenth Congress, Inclusive. Commencing December 27, 1819, and ending February 28, 1825. Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1834.

- ^ Lee, Laura M. et al., 2010: p.12.

- ^ Dobbs, Kelli W., et al. 1999, p. 7

- ^ Catts, Coleman and Custer, p. 27, from "Substance of the Argument of John Clayton, of Delaware, for the United States in the matter of Pea Patch Island." Philadelphia: J and G.S. Gideon, 1848, p.6

- ^ West Publishing Company (1897). "The Federal Cases: Comprising Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit and District Courts of the United States from the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the Federal Reporter, Arranged Alphabetically by the Titles of the Cases and Numbered Consecutively, Book 30". Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ Weaver II, John R. (2018). A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867, 2nd Ed. McLean, VA: Redoubt Press. pp. 171–176. ISBN 978-1-7323916-1-1.

- ^ Dobbs, Kelli W., Life Outside These Walls: A Study of Community Life on Pea Patch Island, Fort Delaware, 1848-1860.Newark, DE: University of Delaware, Spring 1999.

- ^ Record Group 77: Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers. National Archives and Records Administration, Philadelphia Branch.

- ^ Dobbs, Kelli W., Life Outside These Walls, 1999, p. 38.

- ^ Dobbs, Kelli W., et al., 1999.

- ^ a b Dobbs, Kelli W., Life Outside These Walls, 1999, p. 40.

- ^ Dobbs, Kelli W., Life Outside These Walls, 1999, pp. 39-41.

- ^ a b Dobbs, Kelli, et al, 1999: p.11

- ^ Snyder, Frank E., Brian H. Guss. The District: A History of the Philadelphia District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1866-1971. Library of Congress, January 1974, pp. 56-57.

- ^ a b Dobbs, Kelli, et al, 1999: p.12

- ^ "Capt John Sanders (1810-1858) Find A Grave-herdenking". Find a Grave.

- ^ Wilson, W. Emerson., A Fort Delaware Journal: The Diary of a Yankee Private, A.J. Hamilton, 1862-65, Wilmington, DE: Fort Delaware Society, 1981.

- ^ Berkeley, Henry R., Four years in the Confederate Artillery: The Diary of Private Henry Robinson Berkeley. Richmond, VA: Virginia Historical Society, 1991., p. 128.

- ^ Dawson, Francis W., Reminiscences of Confederate Service, 1861-1865. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1980., pp. 72-73.

- ^ Philadelphia Inquirer, Local Intelligence, Matters at Fort Delaware. July 21, 1862, p. 8.

- ^ Jamison, Jocelyn P., They Died at Fort Delaware 1861-1865: Confederate, Union and Civilian. Delaware City, DE: Fort Delaware Society, 1997

- ^ Jamison, Jocelyn P., 1997., referencing House Report No. 45.

- ^ Jamison, Jocelyn P., 1997., pp. 91-94.

- ^ a b Mowday, Bruce., and Dale Fetzer, Unlikely Allies: Fort Delaware's Prison Community in the Civil War, Stackpole Books, 2000.

- ^ Jamison, Jocelyn P., 1997., pp. 85-90.

- ^ "Finn's Point National Cemetery". National Cemetery Administration. United States Department of Veterans Affairs. August 28, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Handy, Isaac W.K., United States Bonds Or Duress By Federal Authority: A Journal Of Current Events During An Imprisonment Of Fifteen Months, At Fort Delaware, Turnbull Brothers, 1874.

- ^ Berkley, 1999., p. 129.

- ^ Park, Robert Emory (January 1877). . Southern Historical Society Papers. Vol. 3. Richmond, VA: Southern Historical Society. p. 43 – via Wikisource. [scan

]

]

- ^ Schiller, Herbert M., edited, A Captain's War: The Letters and Diaries of William H. S. Burgwyn, 1861-1865. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., 1994., p. 160.

- ^ Handy, Isaac W.K., 1874., pp. 13-16.

- ^ Rosenburg, R.B., "For The Sake of My Country": The Diary of Col. W. W. Ward., 9th Tennessee Cavalry, Morgan's Brigade, C. S. A. Murfreesboro, TN: Southern Heritage Press, 1992., pp. 24-26.

- ^ Rosenburg, R.B., 1992., pp. 24-25.

- ^ Handy, Isaac W.K., 1874. pp. 336-347.

- ^ Dawson, Francis W., 1980., pp. 73-74.

- ^ Dawson, Francis W., 1980., p. 73.

- ^ Pinkowski, Edward. Pills, Pen & Politics: The Story of General Leon Jastremski, 1843-1907. Wilmington, DE: Captain Stanislaus Mlotkowski Memorial Brigade Society, 1974., pp. 62-63.

- ^ Wilson, Emerson E., 1981., pp. 58-59.

- ^ Handy, Isaac W.K., 1873., pp. 514-515.

- ^ Hagerty, Edward J., Collis' Zouaves: The 114th Pennsylvania Volunteers in the Civil War. Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1997. pp. 26-27.

- ^ "History - Pennsylvania Artillery (Part 2)". www.civilwararchive.com. American The Civil War Archive. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Wilson, W. Emerson., 1981., p. 82.

- ^ "History - Delaware Troops". www.civilwararchive.com. American The Civil War Archive. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Fletcher, William J. A Soldier for One Hundred Days, Madison: WI, 1955.

- ^ "Fort DuPont (1)". www.fortwiki.com. FortWiki Historic U.S. and Canadian Forts. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Maxwell, James., Letter to the Asst. Adjutant General, headquarters, Department of the East, New York Harbor, August 4, 1885.

- ^ a b c Berhow 2015, p. 210.

- ^ a b c dev. "The Harbor Defenses of the Delaware". cdsg.org.

- ^ Berhow, Mark A., Ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide, Third Edition. McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee, Laura M., Brendan Mackie. Images of America: Fort Delaware Arcadia Publishing, 2010.

- ^ "Fort Hancock (2)". www.fortwiki.com. FortWiki Historic U.S. and Canadian Forts. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Fort Delaware". www.fortwiki.com. FortWiki Historic U.S. and Canadian Forts. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Mackie, Brendan., Peter K. Morrill, Laura M. Lee. Images of America: Fort DuPont. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2011.

- ^ "Category:Harbor Defense of the Delaware". www.fortwiki.com. FortWiki Historic U.S. and Canadian Forts. Retrieved January 31, 2019m.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ Berhow 2015, pp. 210, 226.

- ^ "Forts Ferry Crossing". VisitNJ.org. VisitNY.org. May 15, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- Parts of the article adapted from a Senate website, a product of the US Government

- History of Ft. Delaware at the Wayback Machine (archived September 15, 2006)

Bibliography

- Laura M. Lee and Brendan Mackie, Images of America: Fort Delaware, Arcadia Publishers: 2010.

- Burbey, Louis H. Our Worthy Commander: The Life and Times of Benjamin K. Pierce, in Whose Honor Fort Pierce Was Named. Fort Pierce, FL: Indian River Community College Press, 1976.

- Burgwyn, William H.S. A Captain's War: The Letters and Diaries of William H. S. Burgwyn, 1861-1865. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Company, Inc., 1994.

- Duke, Basil W. The Civil War Reminiscences of General Basil W. Duke, C.S.A. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Press, 1976.

- Basil W. Duke, former prisoner, Morgan's Cavalry, Neale Publishing Company, New York and Washington: 1906.

- Fletcher, William J., 6th Massachusetts Infantry, A Soldier for One-Hundred Days, 1955.

- Harold Bell Hancock, Delaware During the Civil War: A Political History, Wilmington, DE: Delaware Historical Society, 1961.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Bruce Mowday and Dale Fetzer, Unlikely Allies: Fort Delaware's Prison Community in the Civil War Stackpole Books, 2000.

- Nugent, Washington G. My Darling Wife: The Letters of Washington George Nugent, Surgeon, Army of the Potomac. Maria Randall Allen, ed. Cheshire, CT: Ye Olde Book Bindery, 1994.

- W. Emerson Wilson, ed., A Fort Delaware Journal: The Diary of a Yankee Private, A.J. Hamilton, 1862–65, Wilmington, DE: Fort Delaware Society, 1981.

External links

- Fort Delaware Society

- Map of HD Delaware at FortWiki.com

- American Forts Network, lists forts in the US, former US territories, Canada, and Central America

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- FortWiki, lists most CONUS and Canadian forts

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. DE-194, "Fort Delaware", 37 photos, 2 data pages, 2 photo caption pages

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. DE-56, "Fort Delaware", 1 photo, 15 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. DE-56-A, "Fort Delaware, Sea Wall", 15 photos, 15 data pages, 3 photo caption pages

- Escape from Fort Delaware triathlon

- Infrastructure completed in 1868

- Delaware City, Delaware

- American Civil War forts

- Buildings and structures on the Delaware River

- Forts in Delaware

- American Civil War prison camps

- Defunct prisons in Delaware

- Delaware in the American Civil War

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Delaware

- Historic American Engineering Record in Delaware

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in Delaware

- Museums in New Castle County, Delaware

- American Civil War museums in Delaware

- Reportedly haunted locations in Delaware

- Buildings and structures in New Castle County, Delaware

- 1846 establishments in Delaware

- National Register of Historic Places in New Castle County, Delaware

- American Civil War on the National Register of Historic Places