Ginevra King

Ginevra King | |

|---|---|

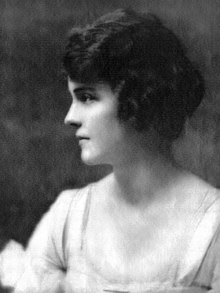

A 20-year-old Ginevra King on the July 1918 cover of Town & Country magazine | |

| Born | November 30, 1898 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 13, 1980 (aged 82) |

| Alma mater | Westover School (expelled) |

| Occupation | Socialite |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives |

|

Ginevra King Pirie (November 30, 1898 – December 13, 1980) was an American socialite and heiress.[1] As one of Chicago's "Big Four" debutantes during World War I,[2] she inspired many characters in the novels and stories of writer F. Scott Fitzgerald; in particular, the character of Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby.[3] A 16-year-old King met an 18-year-old Fitzgerald at a sledding party in St. Paul, Minnesota, and they shared a passionate romance from 1915 to 1917.[4]

Although King was "madly in love" with Fitzgerald,[5] their relationship stagnated when King's family intervened.[6] Her father Charles Garfield King purportedly warned the young writer that "poor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls",[6] and he forbade any further courtship of his daughter by Fitzgerald.[a][6] When their relationship ended, a heartbroken Fitzgerald dropped out of Princeton University and enlisted in the United States Army amid World War I.[7] While courting his future wife Zelda Sayre and other young women while garrisoned near Montgomery, Alabama, Fitzgerald continued to write King in the hope of rekindling their relationship.[8]

While Fitzgerald served in the army, King's father arranged his daughter's marriage to William "Bill" Mitchell, the son of his wealthy business associate John J. Mitchell.[9][10] An avid polo player and sportsman, Bill Mitchell would become the director of Texaco, one of the largest and most successful oil companies of the era,[11] and he served as the model for Thomas "Tom" Buchanan in The Great Gatsby.[b][12] Despite King marrying Mitchell and Fitzgerald marrying Zelda Sayre, Fitzgerald remained "so smitten by King that for years he could not think of her without tears coming to his eyes".[13] Fitzgerald scholar Maureen Corrigan notes that Ginevra King, far more so than author's wife Zelda Sayre, became "the love who lodged like an irritant in Fitzgerald's imagination, producing the literary pearl that is Daisy Buchanan".[14]

During her relationship with Fitzgerald, Ginevra wrote a Gatsby-like story which she sent to the young author.[15] In her story, she is trapped in a loveless marriage with a wealthy man yet still pines for Fitzgerald.[15] The lovers are reunited only after Fitzgerald has attained enough money to take her away from her adulterous husband.[15] Fitzgerald kept Ginevra's story with him until his death, and scholars have noted the plot similarities between Ginevra's story and Fitzgerald's novel.[15]

King divorced Mitchell in 1937 after an unhappy marriage.[13] Following her divorce, Fitzgerald attempted to reunite with King when she visited Hollywood in 1938.[16] The reunion proved a disaster due to Fitzgerald's alcoholism, and a disappointed King returned to Chicago.[16][17] She later married John T. Pirie Jr., a business tycoon and owner of the Chicago department retailer Carson Pirie Scott & Company.[18] She died in 1980 at the age of 82 at her estate in Charleston, South Carolina.[18]

Early life and education

Born in Chicago in 1898, King was the eldest daughter of socialite Ginevra Fuller (1877–1964) and Chicago financier Charles Garfield King (1874–1945).[19][20] She had two younger sisters, Marjorie and Barbara.[19] Like her mother and her grandmother, her name derived from a 15th-century Florentine aristocratic woman whom Leonardo da Vinci's painted in his work Ginevra de' Benci.[21] Both sides of Ginevra's family were extravagantly wealthy,[22] and they exclusively socialized with the other "old money" families in Chicago such as the Mitchells, Armours, Cudahys, Swifts, McCormicks, Palmers, and Chatfield-Taylors.[23] The privileged children of these prominent Chicago families played together during idyllic summers, attended the same private schools, and were expected to endogamously marry within this small social circle.[9][23]

Raised in luxury at her family's sprawling estate in the racially segregated White Anglo-Saxon Protestant township of Lake Forest,[24][25][14] Ginevra enjoyed a carefree "life of tennis, polo ponies, private-school intrigues, and country-club flirtations".[14] Due to her family's immense wealth, the Chicago press obsessively chronicled Ginevra's mundane social activities, and newspaper columnists feted the young Ginevra as one of the city's "Big Four" debutantes.[2] Accordingly, King developed "a clear sense of her family's wealth and position and, from an early age, a highly developed understanding of how social status worked".[26] She only socialized in an elite circle of the Big Four quartet which included Edith Cummings, Courtney Letts, and Margaret Carry:[27]

The [Big Four] girls went to dances and house parties together, and they were seen as a foursome on the golf links and tennis courts at Onwentsia. If other girls were jealous, Ginevra and her three friends did not care. The Big Four was complete; it would admit no further members.[28]

"She's got an indiscreet voice," I remarked."It's full of—" I hesitated.

"Her voice is full of money," he said suddenly.

That was it. I'd never understood before. It was full of money—that was the inexhaustible charm that rose and fell in it, the jingle of it, the cymbals' song of it.... High in the white palace the king's daughter, the golden girl....

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby[29]

As a privileged teenager cocooned in a small circle of wealthy Protestant families, King developed a notorious self-centeredness,[30] and she purportedly lacked self-introspection.[31] Intensely competitive, King disliked to lose to anyone at anything—tennis, golf or basketball.[32] This intense competitiveness did not extend to her academic studies.[33] Although she diligently completed her schoolwork, she disliked learning and instead preferred parties where she could sit up late chatting with her Big Four friends.[33] Her closest friend and confidant in the Big Four quartet, Edith Cummings, later became one of the premier amateur golfers during the Jazz Age and served as the model for the character of Jordan Baker in Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby.[34]

In 1914, King's father sent Ginevra to Middlebury, Connecticut, to attend the Westover School, an exclusive finishing school for the daughters of America's wealthiest families.[35] Her Westover schoolmates included such notable persons as Isabel Stillman Rockefeller of the Rockefeller dynasty, as well as Margaret Livingston Bush and Mary Eleanor Bush,[c] the aunts of President George H. W. Bush.[37] The school overtly prided itself on inculcating a sense of duty and noblesse oblige in its pupils.[38] Most of Westover's attendees later became the wives of wealthy men who sought "fulfillment in social activities, in child-rearing, and, if they wished to, in helping the needy."[38]

Relationship with Fitzgerald

"Some day—Scott—some day. Perhaps in a year—two—three—We'll have that perfect hour! I want it—and so we'll have it! It may be different then but after a while we would be brought back to the way I feel now..."

—Ginevra King, Letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald, February 1915[39]

While visiting her Westover roommate Marie Hersey in St. Paul, Minnesota,[d][40] Ginevra King met F. Scott Fitzgerald at a sledding party on Summit Avenue on January 4, 1915,[41] She was a 16-year-old at the Westover School and he was a 18-year-old at Princeton.[42] According to letters and diary entries, the two teenagers immediately fell in love.[43][5]

After their first meeting, Ginevra returned to Westover School in Connecticut, and Fitzgerald deluged Ginevra with voluminous correspondence which pleased her as she measured her popularity "in part by which boys wrote to her and how many letters she received".[44] Against his wishes, Ginevra read Fitzgerald's intimate letters aloud to her Westover classmates for their amusement.[45] At one point, Ginevra asked for a photograph of him as she coyly professed to recall only that he had "yellow hair" and "blue eyes".[46]

The lovers corresponded back and forth for months, and they exchanged numerous photographs. Over time, their letters became increasingly passionate.[13] Ginevra began having erotic dreams about Scott and "slept with his letters" in the hope "that dreams about him would come in the night".[47] Fitzgerald visited Westover several times, and Ginevra wrote in her diary that she was "madly in love with him".[5] In March 1915, Fitzgerald asked Ginevra to be his date for Princeton's sophomore prom, the most anticipated social event of the year for the young writer,[48][49] but Ginevra's mother forbade Ginevra to attend as the consort of the middle-class Fitzgerald.[48]

In February–March 1916, Fitzgerald wrote a short story entitled "The Perfect Hour" in which he imagined Ginevra and himself blissfully together at last, and he mailed the love story to her by post as a token of his affection.[50] Ginevra read the story aloud to a rival suitor who generously praised Fitzgerald's writing as excellent.[50] In response to Fitzgerald's "The Perfect Hour" tale, Ginevra herself wrote a Gatsby-like short story which she sent to Fitzgerald on March 6.[15] In her story, she is trapped in a loveless marriage with a wealthy man yet still pines for Fitzgerald, a former lover from her past.[15] The two lovers are reunited only after Fitzgerald attains enough money to take her away from her adulterous husband.[15] Fitzgerald would keep Ginevra's short story with him until his death, and literary scholars have noted the plot similarities between Ginevra's story and Fitzgerald's work The Great Gatsby.[15]

Despite Fitzgerald's frequent love letters, Ginevra nonetheless continued entertaining other suitors and, on May 22, 1916, Westover School expelled Ginevra for flirting with several young men from her dormitory window.[51] Mary Robbins Hillard, the stern headmistress of Westover school, declared King to be a "bold, bad hussy" and an "adventuress".[52] After legal threats by Ginevra's imperious and influential father, a cowed Hillard readmitted King to the school, but her father—irate at Westover's treatment of his beloved daughter—decided that she instead would complete her education at a New York finishing school.[51] Ginevra recounted these events in her diary:[53]

After all the things that demon [Mary Robbins Hillard] had told me, she was as sweet as sugar to Father, even if he did tell her a few plain truths about herself—You wouldn't have known her for the same woman. She was all smiles, and agreed heartily when Father said he thought the best thing to do would be to take me home, and she was sweet as anything to me when I said "goodbye" to her.... So I left last Monday morn [sic] and since then Pa has gotten a letter [from Hillard] flattering me to the skies, and Father answered her by ripping her clean up the back.[53]

That summer, in August 1916, Fitzgerald again visited Ginevra at her family's Lake Forest villa.[4] At the time, Lake Forest "was off-limits to Black and Jewish people," and the recurrent appearance of a middle-class Irish Catholic parvenu such as Fitzgerald in the exclusively White Anglo-Saxon Protestant township likely caused a stir.[24] During the visit, financier Charles Garfield King became irritated by the impoverished Fitzgerald's continued pursuit of his eldest daughter.[6] He allegedly interrogated the 19-year-old Fitzgerald regarding his financial prospects.[54] Disappointed by Fitzgerald's answers, her father forbade any further courtship of his daughter by Fitzgerald, and he instructed Ginevra to drive Fitzgerald to the nearest train station.[a][54] He purportedly told the young writer that "poor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls".[4] This line later appeared in both the 1974 and 2013 film productions of The Great Gatsby.

Due to her family's intervention, the relationship between Fitzgerald and King stagnated.[55] The final meeting between Fitzgerald and King as a romantic couple occurred in November 1916 at Penn Station when Ginevra visited the Princeton campus for a Princeton-Yale football game.[56] In an interview decades after Fitzgerald's death, King recalled that she was secretly dating a Yale student in New York by this time,[56] and this complicated her final meeting with Fitzgerald who was unaware of the rival suitor awaiting her attentions:[56]

My girlfriend and I had made plans to meet some other, uh, friends. So we said good-bye [to Scott], 'we were going back to school, thanks so much.' Behind the huge pillars in the [train] station there were two guys waiting for us—Yale boys. We couldn't just walk out and leave them standing behind the pillars. Then we were scared to death we'd run into Scott and his friend. But we didn't.[56]

By January 1917, Ginevra had discounted Fitzgerald as a suitor because of his lower-class status and lack of financial prospects.[55] According to Fitzgerald scholar James L. W. West, Ginevra scrutinized Fitzgerald "against the backdrop of Lake Forest by that time, as opposed to seeing him at her school," and she realized the aspiring writer "didn't fit in" with her elite social milieu.[13] A heartbroken Fitzgerald claimed that King rejected him with "supreme boredom and indifference".[13] In the wake of the rejection, a distraught Fitzgerald dropped out of Princeton University and enlisted in the United States Army amid World War I.[7]

Marriages and later years

Fitzgerald continued writing Ginevra while stationed as a military officer near Montgomery, Alabama, and he begged in vain to resume their former relationship.[8] On July 15, 1918, King wrote to Fitzgerald and informed him of her engagement to polo player William "Bill" Mitchell, the son of banker John J. Mitchell, president of the Illinois Trust & Savings Bank and a close personal friend of Charles Garfield King with whom he shared offices in the same building in downtown Chicago.[57][58] Ginevra's father orchestrated the union between his daughter and Mitchell as "an arranged marriage" between two elite Chicago families.[9]

According to Fitzgerald scholar James L. W. West, "Ginevra's marriage to Bill Mitchell was a dynastic affair very much approved by both sets of parents. In fact Bill's younger brother, Clarence, would marry Ginevra's younger sister Marjorie a few years later."[59] By marrying Mitchell, Ginevra "made the same choice Daisy Buchanan did, accepting the safe haven of money rather than waiting for a truer love to come along."[13] "To say I am the happiest girl on earth would be expressing it mildly", King wrote perfunctorily in her letter to Fitzgerald, "I wish you knew Bill so that you could know how very lucky I am".[60]

Ginevra King married William Mitchell at St. Chrysostom's Episcopal Church in Chicago, Illinois, on September 4, 1918.[61] Newspapers described the event as one of the most attended weddings of the season, and Mitchell's parents hosted a lavish wedding reception at the Blackstone Hotel.[62] Fitzgerald kept the wedding invitation and a piece of Ginevra's handkerchief in his scrapbook with the note: "The end of a once poignant story."[63] Three days after Ginevra's marriage, on September 7, 1918, a lonely Fitzgerald professed his affections for Zelda Sayre, a Southern belle whom he had met in Montgomery.[64]

Despite King marrying Mitchell and Fitzgerald marrying Zelda Sayre, Fitzgerald remained "so smitten by King that for years he could not think of her without tears coming to his eyes".[13] In the wake of his failed relationship with Ginevra due to his family's insufficient wealth, Fitzgerald's attitude towards the rich became embittered, and he later wrote in 1926: "Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me. They possess and enjoy early, and it does something to them, makes them soft where we are hard, and cynical where we are trustful, in a way that, unless you were born rich, it is very difficult to understand. They think, deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are."[65]

King and Mitchell had three children, William, Charles, and Ginevra.[66] Their marriage proved to be unhappy.[13] Despite marital discord,[13] Bill Mitchell rose to become the director of Texaco and the Continental Illinois National Bank,[67] and he inspired the character of Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby.[b][63] His brother, banker Jack Mitchell, co-founded United Airlines and married the only daughter of magnate J. Ogden Armour, the second-richest man in the United States after John D. Rockefeller.[70] By 1926, the extended Mitchell family had amassed in excess of $120 million (equivalent to $2,065,263,158 in 2023).[71]

As they walked inside, their voices jingled the words 'all these years', and Donald felt a sinking in his stomach. This derived in part from a vision of their last meeting—when she rode past him on a bicycle, cutting him dead—and in part from fear lest they have nothing to say. It was like a college reunion—but there the failure to find the past was disguised by the hurried boisterous occasion. Aghast, he realized that this might be a long and empty hour.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Three Hours Between Planes, July 1941[72]

In 1937, Ginevra divorced Bill Mitchell.[73] The next year in 1938, Ginevra met a physically ailing Fitzgerald for the last time in Hollywood, California.[e][76] "She was the first girl I ever loved, and I have faithfully avoided seeing her up to this moment to keep the illusion perfect", Fitzgerald informed his daughter Scottie, shortly before the planned meeting.[13] The reunion proved a disaster due to Fitzgerald's uncontrollable alcoholism.[77][17] When Ginevra asked him which characters in his literary works were based upon her, an inebriated Fitzgerald quipped: "—Which bitch do you think you are?"[78] Fitzgerald used this final meeting as the basis for his 1941 short story (posthumously published), Three Hours Between Planes.[79]

In April 1942, over a year after Fitzgerald's death by occlusive coronary arteriosclerosis, King married businessman John T. Pirie, Jr., whom she met during an exclusive North Shore fox hunt.[73] Pirie was the heir presumptive to the Chicago department retailer Carson Pirie Scott & Company.[18] During the posh fox hunt, "a horse balked at a fence, throwing its rider, John Taylor Pirie Jr., to the ground in an unconscious heap, and then bolted across a field".[80] Ginevra "had been following closely behind Pirie, and it took only the sight of him lying on the grass motionless for her to leap to the ground".[80] She "hovered over him until the ambulance arrived, climbed into it after him, and remained with him" for the rest of her life.[80]

After Fitzgerald's death by a heart attack two years later in December 1940, his daughter Scottie sent Ginevra a copy of her letters which Fitzgerald had kept with him until his death.[81] Reviewing her teenage letters to Fitzgerald, Ginevra commented in January 1951: "I managed to gag through them, although I was staggering with boredom at myself by the time I was through. Goodness, what a self-centered little ass I was!"[81]

King later founded the Ladies Guild of the American Cancer Society.[13] She died in 1980 at the age of 82 at her family's estate in Charleston, South Carolina.[18]

Literary legacy

"I've just had rather an unpleasant afternoon. There was a—man I cared about. He told me out of a clear sky that he was poor as a church-mouse. He'd never even hinted it before.... You see, if I'd thought of him as poor—well, I've been mad about loads of poor men, and fully intended to marry them all. But in this case, I hadn't thought of him that way and my interest in him wasn't strong enough to survive the shock."

—Judy Jones, in F. Scott Fitzgerald's Winter Dreams, December 1922[82]

King exerted a great influence on Fitzgerald's writing, far more so than his wife Zelda Sayre.[14] Fitzgerald scholar Maureen Corrigan notes that "because she's the one who got away, Ginevra—even more than Zelda—is the love who lodged like an irritant in Fitzgerald's imagination, producing the literary pearl that is Daisy Buchanan".[14] In the mind of Fitzgerald, King became the prototype of the unobtainable, upper-class woman who embodies the elusive American dream.[60]

Decades after their romance, Fitzgerald still referred to Ginevra as "my first girl 18-20 whom I've used over and over [in my writing] and never forgotten".[14] According to Fitzgerald biographer Arthur Mizener, the author "remained devoted to Ginevra as long as she would allow him to", and she inspired numerous women in his novels and short stories.[83] His work abounds with characters modeled after and inspired by King, which include:[40]

- Isabelle Borgé in This Side of Paradise (1920)[84]

- Kismine Washington in "The Diamond as Big as the Ritz" (1922)[85]

- Judy Jones in "Winter Dreams" (1922)[86]

- Paula Legendre in "The Rich Boy" (1924)[87]

- Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby (1925)[84]

- Josephine Perry in The Basil and Josephine Stories (1928)[88]

- Their meeting in "Babes in the Woods", from the collection Bernice Bobs Her Hair and Other Stories, was reused in This Side of Paradise.

King is featured in the books The Perfect Hour: The Romance of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ginevra King by James L. W. West III and in a fictionalized form in Gatsby's Girl by Caroline Preston.[89] The musical The Pursuit of Persephone tells the story of King's romance with Fitzgerald.[90] She also appears in West of Sunset by Stewart O'Nan, a fictionalized account of Fitzgerald's final years.[91]

See also

- Edith Cummings, a close friend of King's and the inspiration for the character of Jordan Baker

- Big Four, an elite quartet of wealthy Chicago debutantes famous in the Midwest circa World War I

References

Notes

- ^ a b Ginevra King revealed these details of Charles Garfield King's confrontation with Fitzgerald in a private meeting with actor Bruce Dern during the 1970s.[54]

- ^ a b Fitzgerald also based Tom Buchanan on Ginevra's father, Charles Garfield King.[68] Like King, Buchanan is an imperious Yale man and polo player from Lake Forest, Illinois.[68] Another possible model for Tom Buchanan was Southern polo champion and aviator Tommy Hitchcock Jr. whom Fitzgerald met at Long Island parties while in New York.[69]

- ^ In later decades, Margaret Livingston Bush—the sister of Prescott Sheldon Bush—would serve as a trustee of the Westover School in Middlebury, Connecticut.[36]

- ^ Prior to meeting King, Fitzgerald had harbored "an innocent crush" on her roommate Marie Hersey whom he knew "during his youth in St. Paul, Minnesota".[13]

- ^ As he had been an alcoholic for many years,[17] Fitzgerald's heavy drinking undermined his health by the late 1930s.[74] His alcoholism resulted in cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, angina, dyspnea, and syncopal spells.[74] As his health deteriorated, Fitzgerald had told Ernest Hemingway of his fear of dying from congested lungs.[75]

Citations

- ^ Diamond 2012; Bleil 2008, p. 38.

- ^ a b Diamond 2012; Corrigan 2014, p. 59.

- ^ Borrelli 2013; Bleil 2008, p. 43; McKinney 2017; Bruccoli 2002, pp. 53–59; Corrigan 2014, p. 58.

- ^ a b c Smith 2003; Corrigan 2014, p. 61.

- ^ a b c West 2005, p. 35: Contrary to later claims by Ginevra's family, Ginevra wrote in her diary that she was "madly in love with" Fitzgerald: "Oh it was so wonderful to see him again," she wrote on February 20, 1916, "I am madly in love with him. He is so wonderful".

- ^ a b c d Smith 2003; Corrigan 2014, p. 61; Dern 2011.

- ^ a b Mizener 1965, p. 70; Bruccoli 2002, pp. 80, 82.

- ^ a b West 2005, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b c Noden 2003: "On July 15, 1918, [Ginevra] writes to tell [Fitzgerald] that on the following day she will announce her engagement to William Mitchell, in what her granddaughter believes was something of an arranged marriage between two prominent Chicago families."

- ^ Chicago Tribune Staff 1987, p. 30; Bruccoli 2000, pp. 9–11, 246; Bruccoli 2002, p. 86; West 2005, pp. 66–70.

- ^ Mitchell Obituary 1987, p. 30; Chicago Tribune Staff 1987, p. 30.

- ^ Bruccoli 2002, p. 86; Noden 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Noden 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f Corrigan 2014, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h West 2005, pp. 3, 50–51, 56–57.

- ^ a b West 2005, pp. 86–87; Corrigan 2014, p. 59; Smith 2003.

- ^ a b c MacKie 1970, pp. 17: Commenting upon his alcoholism, Fitzgerald's romantic acquaintance Elizabeth Beckwith MacKie stated the author was "the victim of a tragic historic accident—the accident of Prohibition, when Americans believed that the only honorable protest against a stupid law was to break it."

- ^ a b c d Bleil 2008, p. 38; McKinney 2017.

- ^ a b 1910 United States Census

- ^ West 2005, p. 6; Chicago Tribune 1964, p. 15; Chicago Tribune 1945, p. 17.

- ^ West 2005, p. 8; Smith 2003.

- ^ West 2005, pp. 6–10.

- ^ a b West 2005, pp. 6, 67–68; Diamond 2012.

- ^ a b Diamond 2022: "Boundaries have always been paramount in Lake Forest. The town was off-limits to Black and Jewish people for decades, and even during the First World War a middle-class Catholic like Fitzgerald showing up could have caused a stir."

- ^ Dreier, Mollenkopf & Swanstrom 2004, p. 37: "Lacking the outward signs of high status that the landed nobility of Europe once enjoyed, wealthy American families have long maintained social distance from the 'common people' by withdrawing into upper-class enclaves. Often located on forested hills far from the stench and noise of the industrial distracts, places like Greenwich, Connecticut; Lake Forest, Illinois; and Palm Beach, Florida, are 'clear material statement[s] of status, power, and privilege.'"

- ^ West 2005, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Bleil 2008, p. 32; West 2005, pp. 8–9; Diamond 2012.

- ^ West 2005, pp. 8–9; Diamond 2012.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1925, p. 144.

- ^ Bleil 2008, p. 33: Later as an adult, King described her youthful self in a letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald's daughter: "Goodness, what a self-centered little ass I was!"

- ^ West 2005, p. 10.

- ^ West 2005, p. 9.

- ^ a b West 2005, pp. 9–10; Noden 2003.

- ^ Bleil 2008, p. 230; Bruccoli 2000, pp. 9, 211.

- ^ West 2005, p. 11.

- ^ Margaret Bush Obituary 1993.

- ^ Margaret Bush Obituary 1993; Diamond 2012.

- ^ a b West 2005, pp. 11–12; Diamond 2012.

- ^ Bleil 2008, pp. 65–66.

- ^ a b Mizener 1972.

- ^ West 2005, p. 21; Smith 2003.

- ^ Smith 2003.

- ^ Mizener 1972; Noden 2003.

- ^ West 2005, p. 26.

- ^ West 2005, pp. 26–27; Bleil 2008, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Bleil 2008, p. 54; West 2005, p. 28.

- ^ Bleil 2008, p. 107; West 2005, p. 33.

- ^ a b West 2005, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Bleil 2011, p. 15.

- ^ a b West 2005, p. 50.

- ^ a b West 2005, p. 49.

- ^ West 2005, p. 49; Dallas 1944.

- ^ a b West 2005, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b c Dern 2011.

- ^ a b Noden 2003; Mizener 1965, p. 70; Bruccoli 2002, pp. 80, 82.

- ^ a b c d West 2005, pp. 62–64.

- ^ West 2005, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Chicago Tribune Staff 1987, p. 30; Bruccoli 2000, pp. 9–11, 246; Bruccoli 2002, p. 86.

- ^ West 2005, p. 67.

- ^ a b Stepanov 2003.

- ^ West 2005, p. 68; The Dispatch 1918, p. 6.

- ^ The Dispatch 1918, p. 6.

- ^ a b Bruccoli 2002, p. 86.

- ^ West 2005, p. 73.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1989, p. 336.

- ^ 1930 United States Census

- ^ Chicago Tribune Staff 1987, p. 30.

- ^ a b West 2005, pp. 4, 57–59.

- ^ Kruse 2014, pp. 82–88.

- ^ Lewis 2019; Associated Press 1985; Los Angeles Times 1985.

- ^ Los Angeles Times 1985.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1951, p. 465; West 2005, p. 87.

- ^ a b McKinney 2017; Noden 2003.

- ^ a b Markel 2017.

- ^ Hemingway 1964, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Bleil 2008, p. 32.

- ^ Bleil 2008, p. 32; Corrigan 2014, p. 59; Noden 2003; Smith 2003.

- ^ Smith 2003; Noden 2003; Corrigan 2014, p. 59.

- ^ West 2005, p. 87.

- ^ a b c McKinney 2017.

- ^ a b Bleil 2008, p. 33.

- ^ West 2005, Appendix 4: Winter Dreams.

- ^ Bruccoli 2002; Stepanov 2003.

- ^ a b Bleil 2008, p. 43; Stepanov 2003.

- ^ West 2005, p. xiii.

- ^ Bleil 2008, p. 43; Noden 2003; Corrigan 2014, p. 59.

- ^ Corrigan 2014, p. 60.

- ^ Bleil 2008, p. 43; Bleil 2011, p. 19; Noden 2003.

- ^ West 2005; Hughes 2006.

- ^ Jones 2005.

- ^ James 2015.

Works cited

- Bleil, Robert Russell (2011). "Temporary Devotion: The Letters of Ginevra King to F. Scott Fitzgerald". The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review. 9. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press: 2–26. doi:10.2307/41608003. JSTOR 41608003. S2CID 248787527. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- Bleil, Robert Russell (December 2008). Temporarily Devotedly Yours: The Letters of Ginevra King to F. Scott Fizgerald (Thesis). University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- Borrelli, Christopher (May 7, 2013). "Revisiting Ginevra King, The Lake Forest Woman Who Inspired 'Gatsby'". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- Bruccoli, Matthew J., ed. (2000). F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: A Literary Reference. New York City: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-0996-0 – via Google Books.

- Bruccoli, Matthew J. (2002). Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald (2nd rev. ed.). Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-455-9 – via Google Books.

- "Charles G. King, Retired Broker, Dies in Hospital". Chicago Tribune (Saturday ed.). Chicago, Illinois. September 15, 1945. p. 17. Retrieved November 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

Charles Garfield King, 72, of 1530 State pkwy., retired broker whose family is well known in social affairs, died yesterday in the Passavant hospital after a week's illness. After completing his education at the University school and Yale, Mr. King entered the mortgage banking business in 1894.

- Chicago Tribune Staff (March 25, 1987). "Obituaries: William H. Mitchell, 92, Banker, Philanthropist". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. p. 30. Retrieved June 6, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Corrigan, Maureen (September 9, 2014). So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-23008-7 – via Google Books.

- Dallas, John T. (1944). Mary Robbins Hillard. Concord, New Hampshire: Rumford Press. Retrieved January 28, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Dern, Bruce (June 3, 2011). A Conversation with Bruce Dern at the Gold Coast Film Festival: Bruce Dern's Meeting with Ginevra King. Great Neck, New York: Gold Coast International Film Festival. Retrieved November 5, 2022 – via YouTube.

- Diamond, Jason (December 25, 2012). "Where Daisy Buchanan Lived". The Paris Review. New York City. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- Diamond, Jason (February 3, 2022). "The House That Inspired F. Scott Fitzgerald's Daisy Buchanan Turns the Page". Town & Country. New York City. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- Dreier, Peter; Mollenkopf, John; Swanstrom, Todd (2004). Place Matters: Metropolitics for the Twenty-first Century (2nd rev. ed.). University Press of Kansas. p. 37. ISBN 0-7006-1364-1 – via Google Books.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1925). The Great Gatsby. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-1-4381-1454-5. Retrieved October 5, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1989). Bruccoli, Matthew J. (ed.). The Short Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-84250-5 – via Internet Archive.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1951). "Three Hours Between Planes". In Cowley, Malcolm (ed.). The Stories of F. Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. SBN 684-71737-9 – via Internet Archive.

- "Founder of Airline, Reagan's Riding Club Dies at 87". Associated Press. New York City. April 8, 1985. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- Hemingway, Ernest (1964). A Moveable Feast. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-7432-3729-1. LCCN 64-15441 – via Internet Archive.

- Hughes, Evan (May 21, 2006). "'Gatsby's Girl,' by Caroline Preston: Boats Against the Current". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- James, Caryn (February 20, 2015). "'West of Sunset,' by Stewart O'Nan". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- "John J. Mitchell, Co-Founder of United Airlines, Dies at 87". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. April 9, 1985. Retrieved November 27, 2022.

- Jones, Kenneth (April 30, 2005). "New Musical Pursuit of Persephone Tracks Romance of F. Scott Fitzgerald". Playbill. New York City. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- Kruse, Horst H. (2014). F. Scott Fitzgerald at Work: The Making of 'The Great Gatsby'. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1839-0. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2021 – via Google Books.

- Lewis, Mark (Spring 2019). "Leaving El Mirador". Montecito Magazine. Montecito, California: 20–23. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- MacKie, Elizabeth Beckwith (1970). Bruccoli, Matthew J. (ed.). "My Friend Scott Fitzgerald". Fitzgerald/Hemingway Annual. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 16–27. Retrieved September 30, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- "Margaret Bush Clement; Bush's Aunt, 93". The New York Times. New York City. June 2, 1993. p. 20. Retrieved January 2, 2020.

- Markel, Howard (April 11, 2017). "F. Scott Fitzgerald's life was a study in destructive alcoholism". PBS NewsHour. New York City. Retrieved May 3, 2020.

- McKinney, Megan (December 10, 2017). "The Other Pirie Heirs". Classic Chicago Magazine. Chicago, Illinois. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- Mizener, Arthur (1972). Scott Fitzgerald and His World. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-500-13040-7 – via Internet Archive.

- Mizener, Arthur (1965) [1951]. The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-1-199-45748-6 – via Internet Archive.

- New York Times Staff (March 29, 1987). "William H. Mitchell Obituary". The New York Times. New York City. p. 30. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

William H. Mitchell, an investment banker and philanthropist, died Tuesday at his winter home here. He was 92 years old. Mr. Mitchell, of Lake Forest, Ill., founded Mitchell and Hutchins & Company, an investment and banking concern, in Chicago after World War I. He moved it away from banking and investment shortly before the stock market crash of 1929, allowing the company to survive the Depression. Mr. Mitchell was a director of Texaco Inc. and of the Continental Illinois National Bank of Chicago for more than 30 years.

- Noden, Merrell (November 5, 2003). "Fitzgerald's First Love". Princeton Alumni Weekly. Princeton, New Jersey. Archived from the original on January 4, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- "Obituaries: Mrs. Genevra King". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. October 29, 1964. p. 15. Retrieved November 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

Memorial services for Mrs. Ginevra King, 87, of 181 Lake Shore Dr., will be held at 4 p.m. today in St. Chrysostom's Episocoal church, 1424 Dearborn pkwy. Mrs. King died Tuesday. She was the widow of Charles Garfield King, a broker who died in 1945.

- Smith, Dinitia (September 8, 2003). "Love Notes Drenched in Moonlight; Hints of Future Novels in Letters To Fitzgerald". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- "Social and Personal Notes: King–Mitchell Wedding". The Dispatch. East Moline, Illinois. September 4, 1918. p. 6. Retrieved November 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

It is a question whether or not little St. Chrysostom's church will be large enough to hold the many people who are planning to attend the King-Mitchell wedding this afternoon.

- Stepanov, Renata (September 15, 2003). "Family of Fitzgerald's Lover Donates Correspondence". The Daily Princetonian. Princeton, New Jersey. Archived from the original on October 4, 2003. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- West, James L. W. (2005). The Perfect Hour: The Romance of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ginevra King, His First Love. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6308-6 – via Internet Archive.

External links

- Stevens, Ruth. Before Zelda, There Was Ginevra — Princeton Weekly Bulletin — September 7, 2003

- Preston, Caroline. Excerpt: Gatsby's Girl — NPR — Weekend Edition Sunday, May 21, 2006