Gout

| Gout | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Rheumatology, internal medicine |

| Frequency | 1—2% (developed world) |

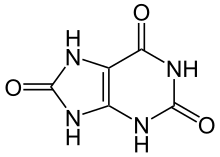

Gout (also known as podagra when it involves the big toe)[1] is a medical condition usually characterized by recurrent attacks of acute inflammatory arthritis—a red, tender, hot, swollen joint. The metatarsal-phalangeal joint at the base of the big toe is the most commonly affected (approximately 50% of cases). However, it may also present as tophi, kidney stones, or urate nephropathy. It is caused by elevated levels of uric acid in the blood. The uric acid crystallizes, and the crystals deposit in joints, tendons, and surrounding tissues.

Clinical diagnosis may be confirmed by seeing the characteristic crystals in joint fluid. Treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), steroids, or colchicine improves symptoms. Once the acute attack subsides, levels of uric acid are usually lowered via lifestyle changes, and in those with frequent attacks, allopurinol or probenecid provide long-term prevention.

Gout has become more common in recent decades, affecting about 1–2% of the Western population at some point in their lives. The increase is believed due to increasing risk factors in the population, such as metabolic syndrome, longer life expectancy and changes in diet. Gout was historically known as "the disease of kings" or "rich man's disease".

Signs and symptoms

Gout can present in a number of ways, although the most usual is a recurrent attack of acute inflammatory arthritis (a red, tender, hot, swollen joint).[2] The metatarsal-phalangeal joint at the base of the big toe is affected most often, accounting for half of cases.[3] Other joints, such as the heels, knees, wrists and fingers, may also be affected.[3] Joint pain usually begins over 2–4 hours and during the night.[3] The reason for onset at night is due to the lower body temperature then.[1] Other symptoms may rarely occur along with the joint pain, including fatigue and a high fever.[1][3]

Long-standing elevated uric acid levels (hyperuricemia) may result in other symptomatology, including hard, painless deposits of uric acid crystals known as tophi. Extensive tophi may lead to chronic arthritis due to bone erosion.[4] Elevated levels of uric acid may also lead to crystals precipitating in the kidneys, resulting in stone formation and subsequent urate nephropathy.[5]

Cause

High levels of uric acid in the blood (hyperuricemia) is the underlying cause of gout. This can occur for a number of reasons, including diet, genetic predisposition, or underexcretion of urate, the salts of uric acid.[2] Renal underexcretion of uric acid is the primary cause of hyperuricemia in about 90% of cases, while overproduction is the cause in less than 10%.[6] About 10% of people with hyperuricemia develop gout at some point in their lifetimes.[7] The risk, however, varies depending on the degree of hyperuricemia. When levels are between 415 and 530 μmol/l (7 and 8.9 mg/dl), the risk is 0.5% per year, while in those with a level greater than 535 μmol/l (9 mg/dL), the risk is 4.5% per year.[1]

Lifestyle

Dietary causes account for about 12% of gout,[2] and include a strong association with the consumption of alcohol, fructose-sweetened drinks, meat, and seafood.[4][8] Other triggers include physical trauma and surgery.[6] Recent studies have found that other dietary factors once believed associated are, in fact, not, including the intake of purine-rich vegetables (e.g., beans, peas, lentils, and spinach) and total protein.[9][10] With respect to risks related to alcohol, beer and spirits appear to have a greater risk than wine.[11]

The consumption of coffee, vitamin C and dairy products, as well as physical fitness, appear to decrease the risk.[12][13][14] This is believed partly due to their effect in reducing insulin resistance.[14]

Genetics

The occurrence of gout is partly genetic, contributing to about 60% of variability in uric acid level.[6] Three genes called SLC2A9, SLC22A12 and ABCG2 have been found commonly to be associated with gout, and variations in them can approximately double the risk.[15][16] Loss of function mutations in SLC2A9 and SLC22A12 cause hereditary hypouricaemia by reducing urate absorption and unopposed urate secretion.[16] A few rare genetic disorders, including familial juvenile hyperuricemic nephropathy, medullary cystic kidney disease, phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthetase superactivity, and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase deficiency as seen in Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, are complicated by gout.[6]

Medical conditions

Gout frequently occurs in combination with other medical problems. Metabolic syndrome, a combination of abdominal obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance and abnormal lipid levels, occurs in nearly 75% of cases.[3] Other conditions commonly complicated by gout include: polycythemia, lead poisoning, renal failure, hemolytic anemia, psoriasis, and solid organ transplants.[6][17] A body mass index greater than or equal to 35 increases a male's risk of gout threefold.[10] Chronic lead exposure and lead-contaminated alcohol are risk factors for gout due to the harmful effect of lead on kidney function.[18] Lesch-Nyhan syndrome is often associated with gouty arthritis.

Medication

Diuretics have been associated with attacks of gout. However, a low dose of hydrochlorothiazide does not seem to increase the risk.[19] Other medicines that increase the risk include niacin and aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid).[4] The immunosuppressive drugs ciclosporin and tacrolimus are also associated with gout,[6] the former more so when used in combination with hydrochlorothiazide.[20]

Pathophysiology

Gout is a disorder of purine metabolism,[6] and occurs when its final metabolite, uric acid, crystallizes in the form of monosodium urate, precipitating in joints, on tendons, and in the surrounding tissues.[4] These crystals then trigger a local immune-mediated inflammatory reaction,[4] with one of the key proteins in the inflammatory cascade being interleukin 1β.[6] An evolutionary loss of uricase, which breaks down uric acid, in humans and higher primates has made this condition common.[6]

The triggers for precipitation of uric acid are not well understood. While it may crystallize at normal levels, it is more likely to do so as levels increase.[4][21] Other factors believed important in triggering an acute episode of arthritis include cool temperatures, rapid changes in uric acid levels, acidosis,[22][23] articular hydration, and extracellular matrix proteins, such as proteoglycans, collagens, and chondroitin sulfate.[6] The increased precipitation at low temperatures partly explains why the joints in the feet are most commonly affected.[2] Rapid changes in uric acid may occur due to a number of factors, including trauma, surgery, chemotherapy, diuretics, and stopping or starting allopurinol.[1] Calcium channel blockers and losartan are associated with a lower risk of gout as compared to other medications for hypertension.[24]

Diagnosis

Gout may be diagnosed and treated without further investigations in someone with hyperuricemia and the classic podagra. Synovial fluid analysis should be done, however, if the diagnosis is in doubt.[1] X-rays, while useful for identifying chronic gout, have little utility in acute attacks.[6]

Synovial fluid

A definitive diagnosis of gout is based upon the identification of monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid or a tophus.[3] All synovial fluid samples obtained from undiagnosed inflamed joints should be examined for these crystals.[6] Under polarized light microscopy, they have a needle-like morphology and strong negative birefringence. This test is difficult to perform, and often requires a trained observer.[25] The fluid must also be examined relatively quickly after aspiration, as temperature and pH affect their solubility.[6]

Blood tests

Hyperuricemia is a classic feature of gout, but it occurs nearly half of the time without hyperuricemia, and most people with raised uric acid levels never develop gout.[3][26] Thus, the diagnostic utility of measuring uric acid level is limited.[3] Hyperuricemia is defined as a plasma urate level greater than 420 μmol/l (7.0 mg/dl) in males and 360 μmol/l (6.0 mg/dl) in females.[27] Other blood tests commonly performed are white blood cell count, electrolytes, renal function, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). However, both the white blood cells and ESR may be elevated due to gout in the absence of infection.[28][29] A white blood cell count as high as 40.0×109/l (40,000/mm3) has been documented.[1]

Differential diagnosis

The most important differential diagnosis in gout is septic arthritis.[3][6] This should be considered in those with signs of infection or those who do not improve with treatment.[3] To help with diagnosis, a synovial fluid Gram stain and culture may be performed.[3] Other conditions that look similar include pseudogout and rheumatoid arthritis.[3] Gouty tophi, in particular when not located in a joint, can be mistaken for basal cell carcinoma,[30] or other neoplasms.[31]

Prevention

Both lifestyle changes and medications can decrease uric acid levels. Dietary and lifestyle choices that are effective include reducing intake of food such as meat and seafood, consuming adequate vitamin C, limiting alcohol and fructose consumption, and avoiding obesity.[2] A low-calorie diet in obese men decreased uric acid levels by 100 µmol/l (1.7 mg/dl).[19] Vitamin C intake of 1,500 mg per day decreases the risk of gout by 45%.[32] Coffee, but not tea, consumption is associated with a lower risk of gout.[33] Gout may be secondary to sleep apnea via the release of purines from oxygen-starved cells. Treatment of apnea can lessen the occurrence of attacks.[34]

Treatment

The initial aim of treatment is to settle the symptoms of an acute attack.[35] Repeated attacks can be prevented by different drugs used to reduce the serum uric acid levels.[35] Ice applied for 20 to 30 minutes several times a day decreases pain.[2][36] Options for acute treatment include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), colchicine and steroids,[2] while options for prevention include allopurinol, febuxostat and probenecid. Lowering uric acid levels can cure the disease.[6] Treatment of comorbidities is also important.[6]

NSAIDs

NSAIDs are the usual first-line treatment for gout, and no specific agent is significantly more or less effective than any other.[2] Improvement may be seen within four hours, and treatment is recommended for one to two weeks.[2][6] They are not recommended, however, in those with certain other health problems, such as gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure, or heart failure.[37] While indomethacin has historically been the most commonly used NSAID, an alternative, such as ibuprofen, may be preferred due to its better side effect profile in the absence of superior effectiveness.[19] For those at risk of gastric side effects from NSAIDs, an additional proton pump inhibitor may be given.[38]

Colchicine

Colchicine is an alternative for those unable to tolerate NSAIDs.[2] Its side effects (primarily gastrointestinal upset) limit its usage.[39] Gastrointestinal upset, however, depends on the dose, and the risk can be decreased by using smaller yet still effective doses.[19] Colchicine may interact with other commonly prescribed drugs, such as atorvastatin and erythromycin, among others.[39]

Steroids

Glucocorticoids have been found as effective as NSAIDs[40] and may be used if contraindications exist for NSAIDs.[2] They also lead to improvement when injected into the joint; a joint infection must be excluded, however, as steroids worsens this condition.[2]

Pegloticase

Pegloticase (Krystexxa) was approved in the USA to treat gout in 2010.[41] It is an option for the 3% of people who are intolerant to other medications.[41] Pegloticase is administered as an intravenous infusion every two weeks,[41] and has been found to reduce uric acid levels in this population.[42]

Prophylaxis

A number of medications are useful for preventing further episodes of gout, including xanthine oxidase inhibitor (including allopurinol and febuxostat) and uricosurics (including probenecid and sulfinpyrazone). They are not usually commenced until one to two weeks after an acute attack has resolved, due to theoretical concerns of worsening the attack,[2] and are often used in combination with either an NSAID or colchicine for the first three to six months.[6] They are not recommended until a person has had two attacks of gout,[2] unless destructive joint changes, tophi, or urate nephropathy exist,[5] as medications have not been found cost effective until this point.[2] Urate-lowering measures should be increased until serum uric acid levels are below 300–360 µmol/l (5.0–6.0 mg/dl), and are continued indefinitely.[2][6] If these medications are being used chronically at the time of an attack, discontinuation is recommended.[3] If levels cannot be brought below 6.0 mg/dl and there are recurrent attacks, this is deemed treatment failure or refractory gout.[43] Overall, probenecid appears less effective than allopurinol.[2]

Uricosuric medications are typically preferred if undersecretion of uric acid, as indicated by a 24-hour collection of urine results in a uric acid amount of less than 800 mg, is found.[44] They are, however, not recommended if a person has a history of kidney stones.[44] In a 24-hour urine excretion of more than 800 mg, which indicates overproduction, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor is preferred.[44]

Xanthine oxidase inhibitors (including allopurinol and febuxostat) block uric acid production, and long-term therapy is safe and well tolerated, and can be used in people with renal impairment or urate stones, although allopurinol has caused hypersensitivity in a small number of individuals.[2] In such cases, the alternative drug, febuxostat, has been recommended.[45]

Prognosis

Without treatment, an acute attack of gout usually resolves in five to seven days; however, 60% of people have a second attack within one year.[1] Those with gout are at increased risk of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and renal and cardiovascular disease, thus are at increased risk of death.[6][46] This may be partly due to its association with insulin resistance and obesity, but some of the increased risk appears to be independent.[46]

Without treatment, episodes of acute gout may develop into chronic gout with destruction of joint surfaces, joint deformity, and painless tophi.[6] These tophi occur in 30% of those who are untreated for five years, often in the helix of the ear, over the olecranon processes, or on the Achilles tendons.[6] With aggressive treatment, they may dissolve. Kidney stones also frequently complicate gout, affecting between 10 and 40% of people, and occur due to low urine pH promoting the precipitation of uric acid.[6] Other forms of chronic renal dysfunction may occur.[6]

-

Nodules of the finger and helix of the ear representing gouty tophi

-

Tophus of the knee

-

Tophus of the toe, and over the external malleolus

-

Gout complicated by ruptured tophi (exudate tested positive for uric acid crystals)

Epidemiology

Gout affects around 1–2% of the Western population at some point in their lifetimes, and is becoming more common.[2][6] Rates of gout have approximately doubled between 1990 and 2010.[4] This rise is believed due to increasing life expectancy, changes in diet, and an increase in diseases associated with gout, such as metabolic syndrome and high blood pressure.[10] A number of factors have been found to influence rates of gout, including age, race, and the season of the year. In men over the age of 30 and women over the age of 50, prevalence is 2%.[37]

In the United States, gout is twice as likely in African American males as it is in European Americans.[47] Rates are high among the peoples of the Pacific Islands and the Māori of New Zealand, but rare in Australian aborigines, despite a higher mean concentration of serum uric acid in the latter group.[48] It has become common in China, Polynesia, and urban sub-Saharan Africa.[6] Some studies have found attacks of gout occur more frequently in the spring. This has been attributed to seasonal changes in diet, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and temperature.[49]

History

The word "gout" was initially used by Randolphus of Bocking, around 1200 AD. It is derived from the Latin word gutta, meaning "a drop" (of liquid).[50] According to the Oxford English Dictionary, this is derived from humorism and "the notion of the 'dropping' of a morbid material from the blood in and around the joints".[51]

Gout has, however, been known since antiquity. Historically, it has been referred to as "the king of diseases and the disease of kings"[6][52] or "rich man's disease".[53] The first documentation of the disease is from Egypt in 2,600 BC in a description of arthritis of the big toe. The Greek physician Hippocrates around 400 BC commented on it in his Aphorisms, noting its absence in eunuchs and premenopausal women.[50][54] Aulus Cornelius Celsus (30 AD) described the linkage with alcohol, later onset in women, and associated kidney problems:

Again thick urine, the sediment from which is white, indicates that pain and disease are to be apprehended in the region of joints or viscera... Joint troubles in the hands and feet are very frequent and persistent, such as occur in cases of podagra and cheiragra. These seldom attack eunuchs or boys before coition with a woman, or women except those in whom the menses have become suppressed... some have obtained lifelong security by refraining from wine, mead and venery.[55]

In 1683, Thomas Sydenham, an English physician, described its occurrence in the early hours of the morning, and its predilection for older males:

Gouty patients are, generally, either old men, or men who have so worn themselves out in youth as to have brought on a premature old age—of such dissolute habits none being more common than the premature and excessive indulgence in venery, and the like exhausting passions. The victim goes to bed and sleeps in good health. About two o'clock in the morning he is awakened by a severe pain in the great toe; more rarely in the heel, ankle or instep. The pain is like that of a dislocation, and yet parts feel as if cold water were poured over them. Then follows chills and shivers, and a little fever... The night is passed in torture, sleeplessness, turning the part affected, and perpetual change of posture; the tossing about of body being as incessant as the pain of the tortured joint, and being worse as the fit comes on.[56]

The Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek first described the microscopic appearance of urate crystals in 1679.[50] In 1848, English physician Alfred Baring Garrod realized this excess uric acid in the blood was the cause of gout.[57]

Other animals

Gout is rare in most other animals due to their ability to produce uricase, which breaks down uric acid.[58] Humans and other great apes do not have this ability, thus gout is common.[1][58] The Tyrannosaurus rex specimen known as "Sue", however, is believed to have suffered from gout.[59]

Research

A number of new medications are under study for treating gout, including anakinra, canakinumab, and rilonacept.[60] A recombinant uricase enzyme (rasburicase) is available; its use, however, is limited, as it triggers an autoimmune response. Less antigenic versions are in development.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Eggebeen AT (2007). "Gout: an update". Am Fam Physician. 76 (6): 801–8. PMID 17910294.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Chen LX, Schumacher HR (2008). "Gout: an evidence-based review". J Clin Rheumatol. 14 (5 Suppl): S55–62. doi:10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181896921. PMID 18830092.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Schlesinger N (2010). "Diagnosing and treating gout: a review to aid primary care physicians". Postgrad Med. 122 (2): 157–61. doi:10.3810/pgm.2010.03.2133. PMID 20203467.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Terkeltaub R (2010). "Update on gout: new therapeutic strategies and options". Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 6 (1): 30–8. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2009.236. PMID 20046204.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Tausche AK, Jansen TL, Schröder HE, Bornstein SR, Aringer M, Müller-Ladner U (2009). "Gout—current diagnosis and treatment". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 106 (34–35): 549–55. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2009.0549. PMC 2754667. PMID 19795010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Richette P, Bardin T (2010). "Gout". Lancet. 375 (9711): 318–28. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60883-7. PMID 19692116.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Vitart V, Rudan I, Hayward C; et al. (2008). "SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout". Nat. Genet. 40 (4): 437–42. doi:10.1038/ng.106. PMID 18327257.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weaver, AL (July 2008). "Epidemiology of gout". Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 75 Suppl 5: S9–12. doi:10.3949/ccjm.75.Suppl_5.S9. PMID 18819329.

- ^ Choi HK, Atkinson K, Karlson EW, Willett W, Curhan G (2004). "Purine-rich foods, dairy and protein intake, and the risk of gout in men". N. Engl. J. Med. 350 (11): 1093–103. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035700. PMID 15014182.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Weaver AL (2008). "Epidemiology of gout". Cleve Clin J Med. 75 Suppl 5: S9–12. doi:10.3949/ccjm.75.Suppl_5.S9. PMID 18819329.

- ^ Roddy, Edward (Oct 1, 2013). "Gout". BMJ. 347. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5648.

- ^ Hak AE, Choi HK (2008). "Lifestyle and gout". Curr Opin Rheumatol. 20 (2): 179–86. doi:10.1097/BOR.0b013e3282f524a2. PMID 18349748.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Williams PT (2008). "Effects of diet, physical activity and performance, and body weight on incident gout in ostensibly healthy, vigorously active men". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87 (5): 1480–7. PMID 18469274.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Choi HK (2010). "A prescription for lifestyle change in patients with hyperuricemia and gout". Curr Opin Rheumatol. 22 (2): 165–72. doi:10.1097/BOR.0b013e328335ef38. PMID 20035225.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Merriman, TR (2011). "The genetic basis of hyperuricaemia and gout". Joint, bone, spine : revue du rhumatisme. 78 (1): 35–40. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.02.027. PMID 20472486.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Reginato AM, Mount DB, Yang I, Choi HK (2012). "The genetics of hyperuricaemia and gout". Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 8 (10): 610–21. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2012.144. PMC 3645862. PMID 22945592.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stamp L, Searle M, O'Donnell J, Chapman P (2005). "Gout in solid organ transplantation: a challenging clinical problem". Drugs. 65 (18): 2593–611. doi:10.2165/00003495-200565180-00004. PMID 16392875.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Loghman-Adham M (1997). "Renal effects of environmental and occupational lead exposure". Environ. Health Perspect. 105 (9). Brogan & Partners: 928–38. doi:10.2307/3433873. JSTOR 3433873. PMC 1470371. PMID 9300927.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Laubscher T, Dumont Z, Regier L, Jensen B (2009). "Taking the stress out of managing gout". Can Fam Physician. 55 (12): 1209–12. PMC 2793228. PMID 20008601.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Firestein, MD, Gary S.; Budd, MD, Ralph C.; Harris Jr., MD, Edward D.; McInnes PhD, FRCP, Iain B.; Ruddy, MD, Shaun; Sergent, MD, John S., eds. (2008). "Chapter 87: Gout and Hyperuricemia". Kelley's Textbook of Rheumatology (8th ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-4842-8.

- ^ Virsaladze DK, Tetradze LO, Dzhavashvili LV, Esaliia NG, Tananashvili DE (2007). "[Levels of uric acid in serum in patients with metabolic syndrome]". Georgian Med News (in Russian) (146): 35–7. PMID 17595458.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moyer RA, John DS (2003). "Acute gout precipitated by total parenteral nutrition". The Journal of rheumatology. 30 (4): 849–50. PMID 12672211.

- ^ Halabe A, Sperling O (1994). "Uric acid nephrolithiasis". Mineral and electrolyte metabolism. 20 (6): 424–31. PMID 7783706.

- ^ Choi HK, Soriano LC, Zhang Y, Rodríguez LA (2012). "Antihypertensive drugs and risk of incident gout among patients with hypertension: population based case-control study". BMJ. 344: d8190. doi:10.1136/bmj.d8190. PMC 3257215. PMID 22240117.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schlesinger N (2007). "Diagnosis of gout". Minerva Med. 98 (6): 759–67. PMID 18299687.

- ^ Sturrock R (2000). "Gout. Easy to misdiagnose". BMJ. 320 (7228): 132–33. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7228.132. PMC 1128728. PMID 10634714.

- ^ Sachs L, Batra KL, Zimmermann B (2009). "Medical implications of hyperuricemia". Med Health R I. 92 (11): 353–55. PMID 19999892.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Gout: Differential Diagnoses & Workup – eMedicine Rheumatology". Medscape.

- ^ "Gout and Pseudogout: Differential Diagnoses & Workup – eMedicine Emergency Medicine". Medscape.

- ^ Jordan DR, Belliveau MJ, Brownstein S, McEachren T, Kyrollos M (2008). "Medial canthal tophus". Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 24 (5): 403–4. doi:10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181837a31. PMID 18806664.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sano K, Kohakura Y, Kimura K, Ozeki S (2009). "Atypical Triggering at the Wrist due to Intratendinous Infiltration of Tophaceous Gout". Hand (N Y). 4 (1): 78–80. doi:10.1007/s11552-008-9120-4. PMC 2654956. PMID 18780009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Choi HK, Gao X, Curhan G (2009). "Vitamin C intake and the risk of gout in men: a prospective study". Arch. Intern. Med. 169 (5): 502–7. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.606. PMC 2767211. PMID 19273781.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Choi HK, Curhan G (2007). "Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and serum uric acid level: the third national health and nutrition examination survey". Arthritis Rheum. 57 (5): 816–21. doi:10.1002/art.22762. PMID 17530681.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Abrams B (2005). "Gout is an indicator of sleep apnea". Sleep. 28 (2): 275. PMID 16171252.

- ^ a b Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T; et al. (2006). "EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: Management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT)". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65 (10): 1312–24. doi:10.1136/ard.2006.055269. PMC 1798308. PMID 16707532.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schlesinger N; Loqueman, N.; Panayi, G. S.; Myles, A. B.; Welsh, K. I.; Rull, M; Hoffman, BI; Schumacher Jr, HR; et al. (2002). "Local ice therapy during bouts of acute gouty arthritis". J. Rheumatol. 29 (2): 331–4. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/29.5.331. PMID 11838852.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b Winzenberg T, Buchbinder R (2009). "Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group review: acute gout. Steroids or NSAIDs? Let this overview from the Cochrane Group help you decide what's best for your patient". J Fam Pract. 58 (7): E1–4. PMID 19607767.

- ^ Clinical Knowledge Summaries. "Gout – Management – What treatment is recommended in acute gout?". National Library for Health. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ a b "Information for Healthcare Professionals: New Safety Information for Colchicine (marketed as Colcrys)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- ^ Man CY, Cheung IT, Cameron PA, Rainer TH (2007). "Comparison of oral prednisolone/paracetamol and oral indomethacin/paracetamol combination therapy in the treatment of acute goutlike arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 49 (5): 670–7. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.11.014. PMID 17276548.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "FDA approves new drug for gout". FDA. September 14, 2010.

- ^ Sundy, JS (Aug 17, 2011). "Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials". JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 306 (7): 711–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1169. PMID 21846852.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ali, S (November 2009). "Treatment failure gout". Medicine and health, Rhode Island. 92 (11): 369–71. PMID 19999896.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 251. ISBN 0-7817-7153-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Febuxostat for the management of hyperuricaemia in people with gout (TA164) Chapter 4. Consideration of the evidence". Guidance.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ^ a b Kim SY, De Vera MA, Choi HK (2008). "Gout and mortality". Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 26 (5 Suppl 51): S115–9. PMID 19026153.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rheumatology Therapeutics Medical Center. "What Are the Risk Factors for Gout?". Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ^ Roberts-Thomson RA, Roberts-Thomson PJ (1999). "Rheumatic disease and the Australian aborigine". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 58 (5): 266–70. doi:10.1136/ard.58.5.266. PMC 1752880. PMID 10225809.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fam AG (2000). "What is new about crystals other than monosodium urate?". Curr Opin Rheumatol. 12 (3): 228–34. doi:10.1097/00002281-200005000-00013. PMID 10803754.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Pillinger, MH (2007). "Hyperuricemia and gout: new insights into pathogenesis and treatment". Bulletin of the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases. 65 (3): 215–221. PMID 17922673.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "gout, n.1". Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition, 1989. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ "The Disease Of Kings - Forbes.com". Forbes.

- ^ "Rich Man's Disease – definition of Rich Man's Disease in the Medical dictionary". Free Online Medical Dictionary, Thesaurus and Encyclopedia.

- ^ "The Internet Classics Archive Aphorisms by Hippocrates". MIT. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Celsus — On Medicine — Book IV". University of Chicago.

- ^ "BBC – h2g2 – Gout – The Affliction of Kings". BBC. May 31, 2006 (updated December 23, 2012).

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Storey GD (2001). "Alfred Baring Garrod (1819–1907)". Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 40 (10): 1189–90. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/40.10.1189. PMID 11600751.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Agudelo CA, Wise CM (2001). "Gout: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and clinical manifestations". Curr Opin Rheumatol. 13 (3): 234–9. doi:10.1097/00002281-200105000-00015. PMID 11333355.

- ^ Rothschild, BM (1997). "Tyrannosaurs suffered from gout". Nature. 387 (6631): 357. doi:10.1038/387357a0. PMID 9163417.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Abeles, A. M. and Pillinger, M. H. (March 8, 2010). "New therapeutic options for gout here and on the horizon". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links