John Walsh (television host)

John Walsh | |

|---|---|

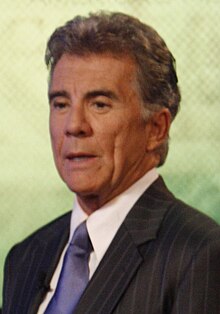

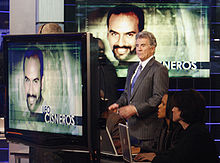

Walsh in September 2008, filming for America's Most Wanted at the now-defunct National Museum of Crime and Punishment (of which he was a co-owner) | |

| Born | John Edward Walsh, Jr. December 26, 1945 Auburn, New York, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University at Buffalo (BA) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1981–present |

| Television | America's Most Wanted The Hunt with John Walsh In Pursuit with John Walsh The Justice Network |

| Spouse |

Revé Drew (m. 1971) |

| Children | 4, including Adam |

| Awards | Operation Kids Lifetime Achievement Award 2008 |

John Edward Walsh, Jr. (born December 26, 1945) is an American television presenter, criminologist, victims' rights activist, and the host/creator[1] of America's Most Wanted. He is known for his anti-crime activism, with which he became involved following the murder of his son, Adam, in 1981; in 2008, deceased serial killer Ottis Toole was officially named as Adam's killer.[2] Walsh was part-owner of the now defunct National Museum of Crime and Punishment in Washington, D.C. He also anchored an investigative documentary series, The Hunt with John Walsh, which debuted on CNN in 2014.

Early life

[edit]Walsh was born in Auburn, New York, one of four children born to John E. Walsh, Sr. and Jean Walsh.[3][4] He graduated from Auburn's Our Lady of Mount Carmel High School in 1963.[4][5] He attended the University at Buffalo, from which he graduated in 1967 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in history. He married Revé Drew in 1971.[5][6][7] After college, the Walshes settled in South Florida, where John became involved in building high-end luxury hotels.[5]

Murder of Adam Walsh

[edit]In summer 1981, Walsh was an official with Paradise Island Hotel and Casino in The Bahamas,[8] and worked in Hollywood, Florida. He and his wife, Revé, had a six-year-old son, Adam. On July 27, 1981, Adam was abducted from a Sears department store at the Hollywood Mall (today Hollywood Hills Plaza), across from the Hollywood Police station. Revé had left Adam in the toy department at a model video game console at the Sears while she looked for a lamp. When she returned several minutes later, Adam was missing. Police records in Adam's case, released in 1996, show that a 17-year-old security guard instructed four boys to leave the department store.[9] Adam is thought to have been one of them. Sixteen days after the abduction, his severed head was found in a drainage canal 120 miles (190 km) away from his home. The rest of his body was never found.[10]

Many names had been mentioned in connection to the case since the murder, but detectives kept returning to that of serial killer Ottis Toole. John Walsh had long said he believed that Toole, a drifter, was responsible for the crime, saying investigators found a pair of green shorts and a sandal similar to what Adam was wearing at Toole's home in Jacksonville, Florida. In January 2007, deceased serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer fell under suspicion for the murder of Adam. This speculation was discounted by Walsh in an America's Most Wanted statement on February 6, 2007.[11]

Toole, the prime suspect in Adam's abduction and murder, died in prison in 1996 while serving a life sentence for other crimes. The Hollywood Police Department officially identified him as Adam's killer on December 16, 2008, and the case was considered closed.[12] Over the years, Toole had twice confessed to the killing, but both times he later recanted his admissions. In addition to the Walsh murder, Toole had claimed responsibility for hundreds of other murders, but police determined that most of these confessions were lies.[13]

Aftermath

[edit]Following the crime, the Walsh family founded the Adam Walsh Child Resource Center, a non-profit organization dedicated to legislative reform.[14] The centers, originally located in West Palm Beach, Florida; Columbia, South Carolina; Orange County, California; and Rochester, New York; merged with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), where John Walsh serves on the board of directors.

The Walsh family organized a political campaign to help missing and exploited children. Despite bureaucratic and legislative problems, John's and Revé's efforts eventually led to the creation of the Missing Children Act of 1982 and the Missing Children's Assistance Act of 1984.

Today, Walsh continues to testify before Congress and state legislatures on crime, missing children and victims' rights issues. His latest efforts include lobbying for a Constitutional amendment for victims' rights.

The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act (Pub. L. 109–248 (text) (PDF)) was signed into law by U.S. President George W. Bush on July 27, 2006, following a two-year journey through the United States Congress. It was intensely lobbied for by Walsh and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Primarily, it focuses on a national sex offender registry, tough penalties for failing to register as a sex offender following release from prison, and civilian access to state websites that track sex offenders. Critics argue that the system amounts to making offenders wear a lifelong "Scarlet Letter", regardless of the circumstances of their cases.

By the late 1990s, many malls, department stores, supermarkets, and other such retailers had adopted what is known as a "Code Adam", a movement first started by Walmart stores in the southeastern United States. A "Code Adam" is announced when a child is missing in a store or if a child is found by a store employee or customer. If the child is lost or missing, all doors will be locked and a store employee is posted at every exit, while a description of the child is generally broadcast over the intercom system. "Code Adam" as a term has become synonymous with a missing child, and is a predecessor to an "Amber Alert", which serves as a system of broadcast-driven community notification.

Career in television

[edit]John and Revé Walsh were portrayed by actors Daniel J. Travanti and JoBeth Williams in Adam, a 1983 NBC television film dramatizing the days following Adam's disappearance. The real Walshes appeared at the end of the broadcast to publicize photographs of other children who had vanished but were still missing. Later, a sequel called Adam: His Song Continues was produced and aired.

After securing a deal with Fox, Walsh launched America's Most Wanted in 1988.[15] By that time, Walsh was already well known because of the murder of his son and his subsequent actions to help missing and exploited children. America's Most Wanted was the longest-running crime reality show in Fox's history and contributed to the capture of more than 1,000 fugitives. Fox canceled the series in June 2011, but aired four specials during the 2011-12 season. On December 2, 2011, the series returned as a regular weekly first-run series on Lifetime. The last episode aired on October 12, 2012; five months later, in March 2013, Lifetime officially canceled the series.

Walsh also hosted his own daytime talk show, The John Walsh Show, which aired in syndication (mostly on NBC-owned and affiliated stations, as NBC produced the series) from 2002 to 2004.[16] However, since America's Most Wanted was still on the air at the time, he found it difficult to host both shows at the same time, so he asked then-NBC Entertainment president Jeff Zucker to release him from his contract. Zucker granted his request and cancelled The John Walsh Show.[17]

In 2003, John Walsh assisted in solving the Kidnapping of Elizabeth Smart on an episode of America's Most Wanted, where Ed Smart showed the picture of Brian David Mitchell's "Emmanuel" appearance. Mitchell's stepchildren saw the episode, identified him, and called the show.[18] This led to the rescue of Elizabeth Smart and the arrests of Brian David Mitchell and Wanda Ilene Barzee. After Elizabeth Smart was reunited with her family, Walsh later met Elizabeth after her family invited him to meet her and mentioned his hand in finding her.

In July 2005, Walsh attempted to assist the family of missing teen Natalee Holloway. Walsh was critical of the Aruban crime investigation and, along with television personality Dr. Phil McGraw, urged Americans to boycott Aruba. Walsh was a special guest on an episode of Extreme Makeover: Home Edition that aired on August 14, 2005. The episode visited the home of Colleen Nick, who is the parent of Morgan Nick, a six-year-old girl who has been missing since 1995. Walsh has featured the Morgan Nick case on America's Most Wanted several times.

Walsh's life story was featured on The E! True Hollywood Story and Biography.

Walsh was later the host of The Hunt with John Walsh, a successor to AMW, which debuted on July 13, 2014 on CNN.[19] The Hunt was in turn succeeded by In Pursuit with John Walsh, which premiered in January 2019 on Investigation Discovery.[20]

On December 13, 2023, it was announced that Walsh would replace Elizabeth Vargas as host of the second season of the revival of America's Most Wanted, with his son Callahan Walsh as co-host. His return marks the first time Walsh has appeared on the show since its March 2013 cancellation.[21] The show premiered on January 22, 2024, with Elizabeth Smart as a guest.[22]

Walsh is also the spokesperson for the American digital multicast network Justice Network.[23][24]

Family

[edit]After the murder of Adam, the Walshes had three more children: Meghan (born 1982), Callahan (born 1985), and Hayden (born 1994).[citation needed] "These kids saved our lives," Walsh has said. He said their home was in foreclosure after the murder as he spent time searching for his son and then for the killer.[25]

Meghan was born a year after Adam was murdered. Revé Walsh told local newspapers at the time that "there is no substitute for Adam." She also said, "Meghan will make me miss Adam more. He always wanted a sister." In a July 27, 2006, family interview on Larry King Live, Meghan said she was living in North Carolina and had recently gotten engaged to a medical student at the University of North Carolina and was still a "daddy's girl". She described herself as an artist who painted commissioned works.[26] She eventually had four children whom she has said were removed from her custody by Florida officials and the oldest were living with her parents. Meghan, who has had basal cell cancer on her nose, appears in videos in which she rails against her father and his work.[27][28][29]

Hayden and Callahan sometimes accompanied their father when filming TV shows, including America's Most Wanted. On a 2006 Larry King Live show, Larry King said that Hayden, then 11, resembled Adam.[26] Hayden, a polo player, worked in production [30][31] and Callahan was a co-host of In Pursuit With John Walsh beginning in 2019. The show told the stories of victims and their families looking for justice for their murdered loved ones. Callahan, a graduate of Stetson University, joined his father as co-host of the 2024 reboot of America's Most Wanted on Fox. "I'm lucky to have Callahan," Walsh told People. "I'm such an old bastard and I'm still cooking, but I got the young legs right here helping me out." Callahan serves as executive director of the Florida branch of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children.[25]

Tributes

[edit]On August 15, 2006, Walsh's hometown of Auburn, New York, named a street after him.[32]

In October 2008, he was awarded the Operation Kids 2008 Lifetime Achievement Award[33][better source needed] for his dedication to protecting children and to raise funds for the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, which Walsh co-founded with his wife.[34]

Controversy

[edit]Walsh generated a great deal of controversy during a summer press tour in 2006 when he stated to the media he had jokingly told senators to implant "exploding" chips in the anuses of sex offenders. He stated, "I said implant it in their anus and if they go outside the radius, explode it, that would send a big message." Walsh stated this was a "joke".[35] Walsh later suggested implanting GPS chips in such criminals.[36]

Walsh also faced criticism when he advised women to never hire a male babysitter, which was seen as a blatantly sexist remark. "It's not a witch hunt," he said. "It's all about minimizing risks. What dog is more likely to bite and hurt you? A Doberman, not a poodle. Who's more likely to molest a child? A male."[37]

In his book Tears of Rage, Walsh openly admits being in a relationship with 16-year-old Revé when Walsh was in his early 20s and aware of the age of consent being 17 in New York.[38]

Some critics accuse Walsh of creating predator panic through his work.[39] Walsh was heard by Congress on February 2, 1983, where he gave an unsourced claim of 50,000 abducted and 1.5 million missing children annually. He testified that the U.S. is "littered with mutilated, decapitated, raped, strangled children,"[40] when in fact, a 1999 Department of Justice study found only 115 incidences of stereotypical kidnappings perpetrated by strangers, about 50 of which resulted in death or the child not being found.[41] Critics have stated that the Adam Walsh Child Resource Center, which started without funding in 1981, generated $1.5 million annually following his testimony before the Congress.[40]

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Type | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988–2012, 2024- | America's Most Wanted: America Fights Back | television series, documentary | self, host | Series first aired on FOX from 1988 to 2011.[42] After the series was cancelled, it was revived on the cable network Lifetime until 2012.[42] On December 13, 2023, it was announced that Walsh would return to the show to host the second season of the FOX revival, effective January 22, 2024.[43] |

| 1998 | Wrongfully Accused | film | self | [44] |

| 1998 | The Wonderful World of Disney presents, Safety Patrol | made-for-television film | self |

Publications

[edit]- Walsh, John; Schindehette, Susan (1997). Tears of Rage. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439189962.

- Walsh, John (1999). No Mercy: The Host of America's Most Wanted Hunts the Worst Criminals of Our Time - In Shattering True Crime Cases. Pocket Star Books. ISBN 9780671019945.

- Walsh, John; Lerman, Philip (2001). Public Enemies: The Host of America's Most Wanted Targets the Nation's Most Notorious Criminals. G.K. Hall. ISBN 9780783897301.

References

[edit]- ^ Katz, Neil (June 3, 2010). "Who Really Killed Adam Walsh? Witness Wants Case Files in Murder of 'America's Most Wanted' Creator's Son". CBS News.

- ^ Holland, John (December 17, 2008). "Adam Walsh case is closed after 27 years". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ Skaine, Rosemarie (April 21, 2015). Abuse: An Encyclopedia of Causes, Consequences, and Treatments. ABC-CLIO. p. 307. ISBN 978-1-61069-515-2.

- ^ a b Cubbison, Brian (March 23, 2019). "John Walsh and CNY". Syracuse.com. Syracuse, NY.

- ^ a b c "Celebrities: John Walsh". TV Guide. New York, NY. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- ^ The Alumni Factor: A Revolution in College Rankings (2013-2014 ed.). The Alumni Factor. September 10, 2013. p. 391. ISBN 978-0-9859765-1-4.

- ^ Lednicer, Lisa Grace (Winter 2015). "Back in the Hunt: The host of 'America's Most Wanted' continues his crusade with a new show on CNN". At Buffalo. Buffalo, NY.

- ^ "Dad pleads for return of 7-year-old son". Florida Today. July 29, 1981. Retrieved August 17, 2016.(subscription required)

- ^ "The Story Of Adam Walsh". America's Most Wanted. Archived from the original on April 3, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ Newton, Michael (2002). The Encyclopedia of Kidnappings. Infobase Publishing. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-4381-2988-4.

- ^ "AMW Statement on Reports Of Possible Adam Walsh/Jeffrey Dahmer Connection". America's Most Wanted. February 6, 2007. Archived from the original on August 6, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ Thomas, Pierre; Michels, Scott (December 16, 2008). "Case Closed: Police ID Adam Walsh Killer". ABC News. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ Wynne, Kelly (December 6, 2019). "The True Story of 'The Confession Killer' Henry Lee Lucas and Serial Killer Ottis Toole". Newsweek. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ Walsh, John (December 1, 2009). Tears of Rage. Simon & Schuster. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-4391-8996-2.

- ^ Grant, Meg. "What I Know Now: John Walsh, host of America's Most Wanted". AARP. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ "The John Walsh Show". IMDb. September 2, 2002. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ Flood, Brian (July 10, 2015). "Why John Walsh is Doubling the Number of Episodes of CNN's 'The Hunt'". Adweek.

- ^ Whitaker, Barbara (March 14, 2003). "End of an Abduction: TV'S Role; 'America's Most Wanted' Enlists Public". The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (July 11, 2014). "Shoe Prints, Dripping Blood and Groping 'Hunt with John Walsh' Goes for Suspects Still at Large". The New York Times. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ "John Walsh to Track Down Fugitives with Real-Time Investigation Series, 'In Pursuit with John Walsh'". The Futon Critic. April 10, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Ausiello, Michael (December 13, 2023). "America's Most Wanted Is Bringing John Walsh Back as Host". TVLine. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ "Elizabeth Smart, kidnapped at 14, shares how she survived". FOX 35 Orlando. January 29, 2024. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "About". justicenetworktv.com. July 6, 2016.

- ^ "Justice Network Debuts With John Walsh". TV News Check. January 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Baker, KC. "John Walsh Returns to TV's America's Most Wanted, This Time with Son Callahan: 'We're Here to Fight Crime' (Exclusive)". Peoplemag. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ a b "Interview With the Walsh Family". transcripts.cnn.com. CNN Transcripts. July 27, 2006. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ Meghan Walsh daughter of John Walsh speaks out #MeghanWalsh 🙏, July 26, 2022, retrieved January 31, 2024

- ^ Walsh, Meghan. "X".

- ^ Daughter of John Walsh speaks out about her brother Adam's death, December 2, 2021, retrieved January 31, 2024

- ^ Walsh, Hayden. "LinkedIn". Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ Giannini, Laura R (January 19, 2017). "Hayden Walsh — Crazy About Polo". Sidelines Magazine. Retrieved January 31, 2024.

- ^ "Council Meeting, August 31, 2006". City of Auburn, NY. August 25, 2006. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ Larsen, Rick (April 9, 2008). "On Saving Children". A Voice for Children. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ "board of directors". National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ de Morales, Lisa (July 26, 2006). "Summer Press Tour, Day 16: An Explosive Interview". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- ^ Porter, Rick; Fienberg, Daniel; Bundy, Brill (July 25, 2006). "News and Notes from Press Tour". Sun-Sentinel.

- ^ Zaslow, Jeffrey (August 23, 2007). "Are We Teaching Our Kids To Be Fearful of Men?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ Walsh, John; Schindehette, Susan (2008). Tears of Rage (From Grieving Father to Crusader for Justice: The Untold Story of the Adam Walsh Case). New York: Pocket Books. p. 9. ISBN 978-1439136348.

I never gave much thought to how old Revé was. She was pretty, and she dressed sharp. And there was also that body. We were starting to kind of hang around together. She took me horseback riding, and we went skiing. She was always into her own thing, and I like that. Then one night Tom Roche was sitting around in my place and picked up a copy of that day's Buffalo Evening News. It was a picture of Revé, who had just won an art contest. 'Holy Jesus, Mary, and Joseph,' Tom said. 'There is a picture of Revé in the paper, John, and she's 16 years old.' But you know, she had this way about her. She had a certain presence. And after a while I just got over how young she was. She was way more sophisticated than anybody in her high school and she always dated older guys. She had a fake ID. That's how she got into Brunner's. She was born with high school. She was into art and her horses. And even then, she always seemed very… I don't know, serene. We weren't madly in love with each other. Though we had a good time together, and I relaxed a little after she turned 17.

- ^ Horowitz, Emily (2007). "Growing Media and Legal Attention to Sex Offenders: More Safety or More Injustice" (PDF). The Journal of the Institute of Justice & International Studies. 7: 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Gill, John Edward (1981). Stolen Children: How and Why Parents Kidnap Their Kids--and What to Do About It (1st ed.). New York: Seaview Books. pp. 1–3. ISBN 0-87223-667-6.

- ^ "Highlights From the NISMART Bulletins" (PDF). U. S. Department of Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Andreeva, Nellie (January 8, 2020). "'America's Most Wanted' Revival With Global Reach In Works At Fox". Deadline. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ^ Ausiello, Michael (December 13, 2023). "America's Most Wanted Is Bringing John Walsh Back as Host". TVLine. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ Petrakis, John (August 24, 1998). "NIELSEN STILL KICKING IN 'WRONGFULLY ACCUSED'". ChicagoTribune.com. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Fleury, Mary Clare. "Crime Fighter: John Walsh of America's Most Wanted", Washingtonian, April 1, 2008.

- America's Most Wanted Archived January 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Profile of John Walsh

- John Walsh at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- On the Safe Side – Internet Safety a safety video by John Walsh

- John Walsh urges passage of Katie's Law

- John Walsh at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television