Lagash

| |

| Alternative name | Al-Hiba |

|---|---|

| Location | Ash Shatrah, Dhi Qar Province, Iraq |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 31°24′41″N 46°24′26″E / 31.41139°N 46.40722°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 400 to 600 ha |

| History | |

| Founded | 3rd millennium BC |

| Periods | Early Dynastic, Sargonic, Ur III |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1887, 1968-1976, 1990, 2019-present |

| Archaeologists | Robert Koldewey, Vaughn E. Crawford, Donald P. Hansen |

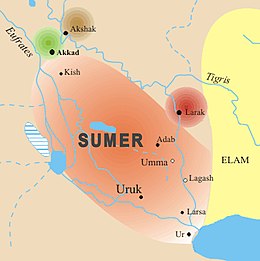

Lagash [4]/ˈleɪɡæʃ/ (cuneiform: 𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠 LAGAŠKI; Sumerian: Lagaš), was an ancient city state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of the modern town of Ash Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash (modern Al-Hiba) was one of the oldest cities of the Ancient Near East. The ancient site of Nina (Tell Zurghul) is around 10 km (6.2 mi) away and marks the southern limit of the state. Nearby Girsu (modern Telloh), about 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Lagash, was the religious center of the Lagash state. Lagash's main temple was the E-ninnu, dedicated to the god Ningirsu. Lagash seems to have incorporated the ancient cities of Girsu, Nina, Uruazagga and Erim.[5]

History

From inscriptions found at Girsu such as the Gudea cylinders, it appears that Lagash was an important Sumerian city in the late 3rd millennium BC. It was at that time ruled by independent kings, Ur-Nanshe (24th century BC) and his successors, who were engaged in contests with the Elamites to the east and the kings of Kienĝir and Kish to the north. Some of the earlier works from before the Akkadian conquest are also extremely interesting, in particular Eanatum's Stele of the Vultures and Entemena's great silver vase ornamented with Ningirsu's sacred animal Anzû: a lion-headed eagle with wings outspread, grasping a lion in each talon. With the Akkadian conquest Lagash lost its independence, its ruler or ensi becoming a vassal of Sargon of Akkad and his successors; but Lagash continued to be a city of much importance and, above all, a centre of artistic development. Early scholars suggested that Lagash was a temple theocracy which had absolute control, but Samuel Noah Kramer argued that further discoveries of documents have shown this to be an error.[6]

After the collapse of Sargon's state, Lagash again thrived under its independent kings (ensis), Ur-Baba and Gudea, and had extensive commercial communications with distant realms. According to his own records, Gudea brought cedars from the Amanus and Lebanon mountains in Syria, diorite from eastern Arabia, copper and gold from central and southern Arabia, while his armies were engaged in battles with Elam on the east. His was especially the era of artistic development. We even have a fairly good idea of what Gudea looked like, since he placed in temples throughout his city numerous statues or idols depicting himself with lifelike realism (Statues of Gudea). At the time of Gudea, the capital of Lagash was actually in Girsu. The kingdom covered an area of approximately 1,600 square kilometres (620 sq mi). It contained 17 larger cities, eight district capitals, and numerous villages (about 40 known by name). According to one estimate, Lagash was the largest city in the world from c. 2075 to 2030 BC.[7]

Soon after the time of Gudea, Lagash was absorbed into the Ur III state as one of its prime provinces.[8] There is some information about the area during the Old Babylonian period. After that it seems to have lost its importance; at least we know nothing more about it until the construction of the Seleucid fortress mentioned, when it seems to have become part of the Iranian kingdom of Characene.

First dynasty of Lagash (c. 2500–2300 BC)

The dynasties of Lagash are not found on the Sumerian King List, although one extremely fragmentary supplement has been found in Sumerian, known as The Rulers of Lagash.[9] It recounts how after the flood mankind was having difficulty growing food for itself, being dependent solely on rainwater; it further relates that techniques of irrigation and cultivation of barley were then imparted by the gods. At the end of the text is the statement "Written in the school", suggesting this was a scribal school production. A few of the names from the Lagash rulers listed below may be made out, including Ur-Nanshe, "Ane-tum", En-entar-zid, Ur-Ningirsu, Ur-Bau, and Gudea.

The First dynasty of Lagash is dated to the 26th century BC. En-hegal was possibly an ancient ruler of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash.[10] The tablet with his name describes a business transaction, in which a possible King En-hegal buys land.[11] If indeed a king of Lagash, it is estimated he would have ruled circa 2570 BCE.[12][13] Both his status and date are disputed.[10]

Lugal-sha-engur was tributary to Mesilim. Following the hegemony of Mesannepada of Ur, Ur-Nanshe succeeded Lugal-sha-engur as the new high priest of Lagash and achieved independence, making himself king. He defeated Ur and captured the king of Umma, Pabilgaltuk. In the ruins of a building attached by him to the temple of Ningirsu, terracotta bas reliefs of the king and his sons have been found, as well as onyx plates and lions' heads in onyx reminiscent of Egyptian work.[14] One inscription states that ships of Dilmun (Bahrain) brought him wood as tribute from foreign lands. He was succeeded by his son Akurgal.

Eannatum, grandson of Ur-Nanshe, made himself master of the whole of the district of Sumer, together with the cities of Uruk (ruled by Enshakushana), Ur, Nippur, Akshak, and Larsa.[14] He also annexed the kingdom of Kish; however, it recovered its independence after his death.[14] Umma was made tributary—a certain amount of grain being levied upon each person in it, that had to be paid into the treasury of the goddess Nina and the god Ningirsu.[14] Eannatum's campaigns extended beyond the confines of Sumer, and he overran a part of Elam, took the city of Uru'az on the Persian Gulf, and exacted tribute as far as Mari; however, many of the realms he conquered were often in revolt.[15] During his reign, temples and palaces were repaired or erected at Lagash and elsewhere; the town of Nina[citation needed]—that probably gave its name to the later Niniveh—was rebuilt, and canals and reservoirs were excavated. Eannatum was succeeded by his brother, En-anna-tum I. During his rule, Umma once more asserted independence under Ur-Lumma, who attacked Lagash unsuccessfully. Ur-Lumma was replaced by a priest-king, Illi, who also attacked Lagash.

His son and successor Entemena restored the prestige of Lagash.[14] Illi of Umma was subdued, with the help of his ally Lugal-kinishe-dudu or Lugal-ure of Uruk, successor to Enshakushana and also on the king-list. Lugal-kinishe-dudu seems to have been the prominent figure at the time, since he also claimed to rule Kish and Ur. A silver vase dedicated by Entemena to his god is now in the Louvre.[14] A frieze of lions devouring ibexes and deer, incised with great artistic skill, runs round the neck, while the Anzû crest of Lagash adorns the globular part. The vase is a proof of the high degree of excellence to which the goldsmith's art had already attained.[14] A vase of calcite, also dedicated by Entemena, has been found at Nippur.[14] After Entemena, a series of weak, corrupt priest-kings is attested for Lagash. The last of these, Urukagina, was known for his judicial, social, and economic reforms, and his may well be the first legal code known to have existed.

| Ruler | Proposed reign | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (En-hegal) |  |

c. 2570 BC | One inscription known, recording a purchase of land.[16] |

| (Lugalshaengur) | c. 2550 BC | High priest or ensi. Mentioned as Ensi of Lagash in a unique inscription on the macehead of Mesilim: “Mesilim, king of Kish, builder of the temple of Ningirsu, brought [this mace head] for Ningirsu, Lugalshaengur [being] prince of Lagash”.[17] | |

| Ur-Nanshe (Ur-nina) |

|

c. 2500 BC | King ("Lugal") |

| Akurgal |  |

c. 2500 BC | King, son of Ur-Nanshe |

| Eannatum |  |

c. 25th century BC | Grandson of Ur-Nanshe, king, took Sumer away from Enshagkushana of Uruk and repulsed the armies of Kish, Elam and Mari |

| Enannatum I | c. 25th century BC | brother to Eanatum, high priest, Ur-Luma and Illi of Umma, as well as Kug-Bau of Kish gained independence from him. | |

| Entemena |  |

c. 25th century BC | Son of Enanatum I, king, contemporary with Lugal-ure (or Lugalkinishedudu) of Uruk and defeated Illi of Umma |

| Enannatum II | Son of Entemena, last member of the dynasty of Ur-Nanshe. | ||

| Enentarzi | A priest of Lagash. | ||

| Lugalanda | |||

| Urukagina | c. 2300 BC | king, defeated by Lugalzagesi of Uruk, issued a proclamation of social reforms. |

-

The cuneiform text states that Enannatum I reminds the gods of his prolific temple achievements in Lagash. Circa 2400 BC. From Girsu, Iraq. The British Museum, London

-

The name "Lagash" (𒉢𒁓𒆷) in vertical cuneiform of the time of Ur-Nanshe.

Border conflict with Umma (c. 2500–2300 BC)

In c. 2450 BC, Lagash and the neighbouring city of Umma fell out with each other after a border dispute. As described in Stele of the Vultures the current king of Lagash, Eannatum, inspired by the patron god of his city, Ningirsu, set out with his army to defeat the nearby city. Initial details of the battle are unclear, but the Stele is able to portray a few vague details about the event. According to the Stele's engravings, when the two sides met each other in the field, Eannatum dismounted from his chariot and proceeded to lead his men on foot. After lowering their spears, the Lagash army advanced upon the army from Umma in a dense phalanx. After a brief clash, Eannatum and his army had gained victory over the army of Umma. Despite having been struck in the eye by an arrow, the king of Lagash lived on to enjoy his army's victory. This battle is one of the earliest organised battles known to scholars and historians.[19]

-

The armies of Lagash led by Eannatum in their conflict against Umma.

-

Lancers of the army of Lagash against Umma

Destruction of Lagash by the Akkadian Empire (circa 2300 BC)

In his conquest of Sumer circa 2300 BC, Sargon of Akkad, after conquering and destroying Uruk, then conquered Ur and E-Ninmar and "laid waste" the territory from Lagash to the sea, and from there went on to conquer and destroy Umma, and he collected tribute from Mari and Elam. He triumphed over 34 cities in total.[22]

Sargon's son and successor Rimush faced widespread revolts, and had to reconquer the cities of Ur, Umma, Adab, Lagash, Der, and Kazallu from rebellious ensis.[23]

Rimush introduced mass slaughter and large scale destruction of the Sumerian city-states, and maintained meticulous records of his destructions.[24] Most of the major Sumerian cities were destroyed, and Sumerian human losses were enormous: for the cities of Ur and Lagash, he records 8,049 killed, 5,460 "captured and enslaved" and 5,985 "expelled and annihilated".[24][25]

Stele of the victory of Rimush over Lagash

A Victory Stele in several fragments (three in total, Louvre Museum AO 2678)[26] has been attributed to Rimush on stylistic and epigraphical grounds. One of the fragments mentions Akkad and Lagash.[20] It is thought that the stele represents the defeat of Lagash by the troops of Akkad.[21] The stele was excavated in ancient Girsu, one of the main cities of the territory of Lagash.[20]

-

Detail

-

Man of Lagash, circa 2270 BC, from the Victory Stele.[29] The same hairstyle can be seen in other statues from Lagash.[30]

Second dynasty of Lagash (c. 2230–2110 BC)

This period lasted c. 2230–2110 BC (Middle chronology). These rulers achieved a Sumerian revival, following the rise and fall of the Semitic Akkadian Empire, and the conquests of the Gutian dynasty.[31] The Second dynasty of Lagash rose at the time the Gutians were ruling in central Mesopotamia.[31] The rulers of Lagash, only taking the title of Ensi, or Governors, achieved to maintain a high level of independence from the Gutians in the southernmost areas of Mesoptamia.[31] Under Gudea, Lagash had a golden age, and seemed to enjoy a high level of independence from the Gutians.[31]

| Ruler | Proposed reign (short chronology) | Proposed reign (middle chronology) | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Lugal-ushumgal) | 2166 – 2146 BC | 2230 – 2210 BC | Vassal of Akkadian Empire rulers Naram-Sin and Shar-Kali-Sharri | |

| (Puzer-Mama) | Wrested independence from the Akkadian Empire | |||

| Ur-Ningirsu I[32][33] | ||||

| Pirig-me or Ugme | Son of Ur-Ningirsu I.[32][33] | |||

| Lu-Baba[34] | ||||

| Lugula[34] | ||||

| Kaku or Kakug[34] | ||||

| Ur-Baba |  |

2093–2080 BC | 2157 – 2144 BC | |

| Gudea |  |

2080–2060 BC | 2144––2124 BC | Son-in-law of Ur-baba |

| Ur-Ningirsu |  |

2060–2055 BC | 2124–2119 BC | Son of Gudea |

| Ur-gar | 2053–2049 BC | 2117–2113 BC | ||

| Nam-mahani | 2049–2046 BC | 2113–2110 BC | Grandson of Kaku, defeated by Ur-Nammu |

Archaeology

Lagash is one of the largest archaeological sitess in the region, measuring roughly 3.5 kilometers north to south and 1.5 kilometers east to west though is relatively low being only 6 meters above the plain level at maximum. A drone survey determined that Lagash developed on four marsh islands some of which were gated.[35] Estimates of its area range from 400 to 600 hectares (990 to 1,480 acres). The site is divided by the bed of a canal/river, which runs diagonally through the mound. The site was first excavated, for six weeks, by Robert Koldewey in 1887.[36] It was inspected during a survey of the area by Thorkild Jacobsen and Fuad Safar in 1953, finding the first evidence of its identification as Lagash. The major polity in the region of al-Hiba and Tello had formerly been identified as ŠIR.BUR.LA (Shirpurla).[37]

Tell Al-Hiba was again explored in five seasons of excavation between 1968 and 1976 by a team from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Institute of Fine Arts of New York University. The team was led by Vaughn E. Crawford, and included Donald P. Hansen and Robert D. Biggs. Twelve archaeological layers were found with the bottom 9 being Early Dynastic and the lowest under the water table. The primary focus was the excavation of the temple Ibgal of Inanna and the temple Bagara of Ningirsu, as well as an associated administrative area.[38][39][40][41] The team returned 12 years later, in 1990, for a sixth and final season of excavation led by D. P. Hansen. The work primarily involved areas adjacent to an, as yet, unexcavated temple Ibgal of the goddess Inanna in the southwest edge of the city. The Bagara temple of Ningirsu was also worked on. Both were built by Early Dynastic III king Eannatum. Temples to the goddesses Gatumdag, Nanshe, and Bau are known to have existed but have not yet been found. A canal linked linked the E-ninnu temple of Ningirsu at Girsu, the E-sirara temple of Nanshe at Nigin, and the Bagara temple at Lagash, the three cities being part of one large state.[42][43] [44] In 1984 a surface survey found that most finds were from the Early Dynastic III period. Small amounts of Uruk, Jemdet Nasr, Isin-Larsa, Old Babylonian and Kassite shards were found in isolated areas.[45]

In March–April 2019, field work resumed as the Lagash Archaeological Project under the directorship of Dr. Holly Pittman of the University of Pennsylvania's Penn Museum in collaboration with the University of Cambridge and University of Pisa. A second season ran from October to November in 2021. A third season ran from March 6 to April 10, 2022. The work primarily involved the Early Dynastic Period Area G and Area H locations along with Geophysical Surveying and Geoarchaeology. The focus was on an industrial area and associated streets, residences, and kilns. Aerial mapping of Lagash, both using UAV drone mapping and satelite imagery was performed.[46]

Area A (Ibgal of Inanna)

Site history

Though commonly known as Area A or the Ibgal of Inanna, this temple complex was actually named Eanna during the Ur periods, while Inanna’s sanctuary within Eanna was known as Ibgal.[47]

Level I architecture

Level I of Area A was occupied from Early Dynastic Ur (ED I) to Ur III.[48] It was used for both daily worshiping activities and festive celebrations, particularly for the queen of Lagash during the Barley and Malt-eating festivals of Nanše.[47][49]

Referring to Hansen’s map in his preliminary report, Level I consists of an oval wall on the Northeast end, surrounding an extensive courtyard. The fragments, together with Hansen’s comparison to another Sumerian temple at Khafajah, show that the wall should originally be approximately 130m long.[50]

For the temple-building, it is connected to the courtyard with steps. 25 rooms have been excavated inside the building, in which the western ones would open up to the outside of the temple with corridors and form a tripartite entrance.[51] Both the temple-building and the oval wall were built with plano-convex mud bricks, which was a very common material during the Ur periods. Additionally, foundations are found under the temple-building. They are composed of rectangular areas of various sizes, some as solid mud bricks and some as cavities of broken pieces of alluvial mud and layers of sand, then capped again with mud bricks.[52]

Level II and Level III architecture

Two more levels are present beneath Level I. Interestingly, all of them are similar to each other in terms of layout and construction materials. During the process of building on top of each other, workers at that time would choose to destroy some portions while keeping some others, leading to much open speculation as to the rationales behind.[53]

Area B (3HB Building and 4HB Building at Bagara of Ningirsu)

The 3HB Building

Basic Information

Three building levels were discovered and 3HB III is the earliest and most well-preserved level.[54] 3HB II and 3HB I shared the same layout with 3HB III.[54]

All three levels have a central niched-and-buttressed building which is surrounded by a low enclosure wall with unknown height.[55]

| Building Level | Building Material | Occupation Period | Notes |

| 3HB III | Plano-convex bricks, mud plaster[54] | ED IIIB | Dimensions:

3HB Building: 24 x 20m[54] Enclosure Wall: approximately 31m x 25m[54] |

| 3HB II | Plano-convex bricks, mud plaster[57] | ED IIIB – Late Akkadian[58] | |

| 3HB I | Plano-convex bricks, mud plaster[59] | Late – Post-Akkadian[55] |

Possible Functions

Hansen believes that the 3HB Building was a “kitchen temple” that aimed at meeting some of the god’s demands.[60] However, Ashby argues that the building was a shrine in the Bagara complex as it shared more similarities with other temples than kitchens in terms of layout, features and contents.[61]

The 4HB Building

Basic Information

The excavators discovered five building levels.[62] The layout of 4HB V cannot be obtained due to limited exploration.[63] 4HB IV-4HB I shared the same layout.[63] 4HB IVB was the first level that was exposed completely.[64]

| Building Level | Building Material | Occupation Period | Notes |

| 4HB V | Plano-convex bricks[63] | ED III

(Evidence from pottery)[64] |

|

| 4HB IVA | Plano-convex bricks[63] | ED III

(Evidence from pottery)[64] |

|

| 4HB IVB | Plano-convex bricks[63] | ED IIIB[65] | Dimensions:

4HB Building: 23 x 14m[64] |

| 4HB III | Plano-convex bricks[63] | ED IIIB – Late Akkadian[66] | |

| 4HB II | Plano-convex bricks[63] | Late – Post-Akkadian[67] | |

| 4HB I | Plano-convex bricks

and flat, square bricks[63] |

Gudea’s rule[67] |

Possible Functions

Hansen suggests that the 4HB Building is a brewery as ovens and storage vats and a tablet mentioning “the brewery” and “a brewer” were found.[68] Ashby proposes another possibility that 4HB building is a kitchen as it shared lots of similarities with temple kitchens at Ur and Nippur.[69]

Area C

Located 360 meters southeast of Area B. It contains a large Early Dynastic administrative area with two building levels (1A and 1B). In level 1B were found sealing and tablets of Eanatum, Enanatum I, and Enmetena.[70]

Area G

Site History

Area G is located at the midway of Area B in the North and Area A in the South. First excavated by Dr Donald P. Hansen in season 3H, Area G consists of a building complex and a curving wall which are separated by around 30-40m.[71]

Western Building Complex

5 building levels are found in the area. There is little information about Levels I and IIA as they were poorly preserved without sealed floor deposits.[72] In Levels IIB, III and IV, changes can be found in the building complex with reconstructions. In Level III, benches are built near the eastern and northern courtyards.[72] Sealings made in the “piedmont” style which are found in the rooms share a resemblance with the Seal Impression Strata of Ur and sealings from Inanna Temple at Nippur,[72] indicating the administrative nature of the buildings. Apart from institutional objects, fireplaces, bins and pottery were found in the rooms as well.[73]

Curving Wall (Eastern Zone)

A 2-m wide wall that runs from the south to the north is found on the eastern part of Area G.[71] The features of the curving wall and the rooms found near it are determined to be different from other oval temples built in the Early Dynastic in other major states.[71] Intrusive vertical drains are found at the base of the plano-convex foundation.[73] Archaeologists excavated further deeper to the water level during season 4H and found extensive Early Dynastic I deposits.[71]

See also

References

- ^ "ETCSLsearch". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ The Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary. "Lagash." Accessed 19 Dec 2010.

- ^ "ePSD: lagaš[storehouse]". Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ Sumerian: Lagaški; cuneiform logogram: 𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠, [NU11.BUR].LAKI[1] or [ŠIR.BUR].LAKI, "storehouse;"[2] Akkadian: Nakamtu;[3] modern Tell al-Hiba, Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq

- ^ Williams, Henry (2018). Ancient Mesopotamia. Ozymandias Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-5312-6292-1.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (17 September 2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-226-45232-6. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Chandler (1987). Four thousand years of urban growth: an historical census. Lewiston (etc.): The Edwin Meller Press. ISBN 978-0-88946-207-6. OCLC 1126378552.

- ^ Westenholz, Joan Goodnick (1984). "Kaku of Ur and Kaku of Lagash". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 43 (4): 339–342. doi:10.1086/373095. ISSN 0022-2968. JSTOR 544849. S2CID 161962784.

- ^ "The rulers of Lagaš". Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Enhegal [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1971). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- ^ "The inscription by an ensi called Enhegal dates from the Early Dynastic period IH, around 2570 BC." in Leick, Gwendolyn (2009). Historical Dictionary of Mesopotamia. Scarecrow Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8108-6324-8.

- ^ Silver, Morris (1995). Economic Structures of Antiquity. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-313-29380-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sayce, Archibald Henry; King, Leonard William; Jastrow, Morris (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–112.

- ^ Steinkeller, Piotr (2018-01-29). "The birth of Elam in history". The Elamite World. Routledge. pp. 177–202. doi:10.4324/9781315658032-11. ISBN 978-1-315-65803-2.

- ^ "Enhegal". Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu.

- ^ "Vase of Lugalzagezi". British Museum. British Museum.

- ^ Grant, R.G. (2005). Battle. London: Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 978-1-74033-593-5.

- ^ a b c Heuzey, Léon (1895). "Le Nom d'Agadé Sur Un Monument de Sirpourla". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 3 (4): 113–117. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23284246.

- ^ a b Thomas, Ariane; Potts, Timothy (2020). Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins. Getty Publications. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-60606-649-2.

- ^ "MS 2814 – The Schoyen Collection". www.schoyencollection.com.

- ^ Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- ^ a b Hamblin, William J. (2006). Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC: Holy Warriors at the Dawn of History. Routledge. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-134-52062-6.

- ^ Crowe, D. (2014). War Crimes, Genocide, and Justice: A Global History. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-137-03701-5.

- ^ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr.

- ^ "Musée du Louvre-Lens - Portail documentaire - Stèle de victoire du roi Rimush (?)". ressources.louvrelens.fr (in French).

- ^ McKeon, John F. X. (1970). "An Akkadian Victory Stele". Boston Museum Bulletin. 68 (354): 235. ISSN 0006-7997. JSTOR 4171539.

- ^ Thomas, Ariane; Potts, Timothy (2020). Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins. Getty Publications. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-60606-649-2.

- ^ Foster, Benjamin R. (1985). "The Sargonic Victory Stele from Telloh". Iraq. 47: 15–30. doi:10.2307/4200229. JSTOR 4200229. S2CID 161961660.

- ^ a b c d Corporation, Marshall Cavendish (2010). Ancient Egypt and the Near East: An Illustrated History. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-0-7614-7934-5.

- ^ a b Edzard, Sibylle; Edzard, Dietz Otto (1997). Gudea and His Dynasty. University of Toronto Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-8020-4187-6.

- ^ a b "Brief notes on Lagash II chronology [CDLI Wiki]". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- ^ a b c "Brief notes on Lagash II chronology". cdli.ox.ac.uk.

- ^ E. Hammer. Multi-centric, marsh-based urbanism at the early Mesopotamian city of Lagash (Tell al-Hiba, Iraq). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. Vol. 68, December 2022, 101458. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2022.101458

- ^ Koldewey, Robert (1887-01-01). "Die altbabylonischen Gräber in Surghul und El Hibba". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie (in German). 2 (Jahresband): 403–430. doi:10.1515/zava.1887.2.1.403. ISSN 1613-1150. S2CID 162346912.

- ^ Amiaud, Arthur. "The Inscriptions of Telloh." Records of the Past, 2nd Ed. Vol. I. Ed. by A. H. Sayce, 1888. Accessed 19 Dec 2010. M. Amiaud notes that a Mr. Pinches (in his Guide to the Kouyunjik Gallery) contended ŠIR.BUR.LAki could be a logographic representation of "Lagash," but inconclusively.

- ^ Donald P. Hansen, "Al-Hiba, 1968–1969: A Preliminary Report", Artibus Asiae, 32 (1970), pp. 243–58

- ^ Donald P. Hansen, "Al-Hiba, 1970–1971: A Preliminary Report", Artibus Asiae, 35 (1973), pp. 62–70

- ^ Donald P. Hansen, "Al-Hiba: A summary of four seasons of excavation: 1968–1976", Sumer, 34 (1978), pp. 72–85

- ^ Vaughn E. Crawford, "Inscriptions from Lagash, Season Four, 1975–76", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 29 (1977), pp. 189–222

- ^ "Excavations in Iraq 1989-1990". Iraq. 53: 169–182. 1991. doi:10.1017/S0021088900004277. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200346. S2CID 249898405.

- ^ Hansen, D. P., "The Sixth Season at Al-Hiba", Mār Šipri 3 (1): 1–3, 1990

- ^ S. Renette, "Lagash I: The Ceramic Corpus from Al-Hiba, 1968–1990 A Chrono-Typology of the Pottery Tradition in Southern Mesopotamia during the 3rd and Early 2nd Millenium BCE", Brepols, 2021 ISBN 978-2-503-59020-2

- ^ E. Carter, "A surface survey of Lagash, al-Hiba", 1984, Sumer, vol. 46/1-2, pp. 60–63, 1990

- ^ [1]Hammer, Emily, Elizabeth Stone, and Augusta McMahon. "The Structure and Hydrology of the Early Dynastic City of Lagash (Tell al-Hiba) from Satellite and Aerial Images." Iraq, vol. 84, pp. 1-25, 2022

- ^ a b Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 86.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 86–87.

- ^ Beld, S. G., "The queen of Lagash: ritual economy in a Sumerian State", Near East Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 2002

- ^ Hansen, Donald P. (1970). "Al-Hiba, 1968-1969, a Preliminary Report". Artibus Asiae. 32 (4): 246. doi:10.2307/3249506. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3249506.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 104.

- ^ Hansen, Donald P. (1970). "Al-Hiba, 1968-1969, a Preliminary Report". Artibus Asiae. 32 (4): 245. doi:10.2307/3249506. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3249506.

- ^ Hansen, Donald P. (1973). "Al-Hiba, 1970-1971: A Preliminary Report". Artibus Asiae. 35 (1/2): 65. doi:10.2307/3249575. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 3249575.

- ^ a b c d e Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 115.

- ^ a b Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 140.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 125.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 126.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 134.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 135.

- ^ Hansen, Donald P. (1992). "Royal Building Activity at Sumerian Lagash in the Early Dynastic Period". The Biblical Archaeologist. 55 (4): 208. doi:10.2307/3210315. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210315. S2CID 166152714.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 187.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 143–44.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 144.

- ^ a b c d Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 145.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 150.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 157.

- ^ a b Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 161.

- ^ Hansen, Donald P. (1992). "Royal Building Activity at Sumerian Lagash in the Early Dynastic Period". The Biblical Archaeologist. 55 (4): 209. doi:10.2307/3210315. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210315. S2CID 166152714.

- ^ Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 204.

- ^ Bahrani, Zainab. The administrative building at Tell Al Hiba, Lagash.(Volumes I and II). New York University, 1989.

- ^ a b c d Ashby, Darren (2017). "Late Third Millennium Bce Religious Architecture At Tell Al-Hiba, Ancient Lagash". Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations: 81.

- ^ a b c "Excavations in Iraq 1989-1990". Iraq. 53: 175. 1991. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 4200346.

- ^ a b Hansen, Donald P. (1992-12-01). "Royal Building Activity at Sumerian Lagash in the Early Dynastic Period". The Biblical Archaeologist. 55 (4): 210. doi:10.2307/3210315. ISSN 0006-0895. JSTOR 3210315. S2CID 166152714.

Sources

- Robert D. Biggs, "Inscriptions from al-Hiba-Lagash : the first and second seasons", Bibliotheca Mesopotamica. 3, Undena Publications, 1976, ISBN 0-89003-018-9

- R. D. Biggs, "Pre-Sargonic Riddles from Lagash", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 32, no. 1/2, pp. 26–33, 1973

- Vaughn E. Crawford, "Lagash", Iraq, vol. 36, no. 1/2, pp. 29–35, 1974

- Foxvog D.A., "Aspects of Name-Giving in Presargonic Lagash", in W. Heimpel – G. Frantz- Szabó (eds.), Strings and Threads: A Celebration of the Work of Anne Draffkorn Kilmer, Winona Lake, 59-97, 2011

- Hansen, D. P., "Lagaš. B. Archäologisch", Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie 6: 422–30, 1980–1983

- Donald P. Hansen, "Royal building activity at Sumerian Lagash in the Early Dynastic Period", Biblical Archaeologist, vol. 55, pp. 206–11, 1992

- [2]Hritz, C., "The Umma-Lagash Border Conflict: A View from Above" in Altaweel, M. and Hritz, C. (eds.), From Sherds to Landscapes: Studies on the Ancient Near East in Honor of McGuire Gibson. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, pp. 109–32, 2021

- Kenoyer, J. M., "Shell artifacts from Lagash, al-Hiba", Sumer 46 (1/2), pp. 64–67, 1989-1990

- Maeda T., "Work Concerning Irrigation Canals in Pre-Sargonic Lagash", Acta Sumerologica Japaniensia 6, 33-53, 1984

- Maekawa K., "The Development of the é-mí in Lagash during Early Dynastic III", Mesopotamia 8-9, 77-144, 1973-1974

- Mudar, K., "Early Dynastic III animal utilization in Lagash: a report on the fauna of Tell al-Hiba", Journal of Near Eastern Studies 41 (1), pp. 23-34, 1982

- Prentice, R., "The exchange of goods and services in pre-Sargonic Lagash", Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, 2010

- Garcia-Ventura, Agnès, and Fumi Karahashi. "Overseers of textile workers in presargonic Lagash.", Overseers of Textile Workers in Presargonic Lagash (2016): KASKAL, 1-19.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lagash". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 72.

External links

- Drone photos reveal an early Mesopotamian city made of marsh islands - Science News - October 13, 2022

- University of Pennsylvania Lagash Current and Legacy excavations page

- Excavations in the Swamps of Sumer - Vaughn E. Crawford - Expedition Magazine Volume 14 Issue 2 1972

- University of Cambridge Lagash project

- Lagash excavation site photographs at the Oriental Institute

- Lagash Digital Tablets at CDLI

- The Al-Hiba Publication Project

- The Al-Hiba Publication Project - digitization

![Possible victory stele of king Rimush (front).[27] Generally attributed to Rimush on stylistic grounds.[28]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f0/Victory_stele-AO_2678-IMG_9053-gradient.jpg/200px-Victory_stele-AO_2678-IMG_9053-gradient.jpg)

![Man of Lagash, circa 2270 BC, from the Victory Stele.[29] The same hairstyle can be seen in other statues from Lagash.[30]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Man_of_Lagash%2C_circa_2270_BCE_%28portrait%29.jpg/174px-Man_of_Lagash%2C_circa_2270_BCE_%28portrait%29.jpg)