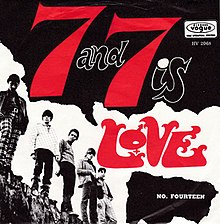

7 and 7 Is

| "7 and 7 Is" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Love | ||||

| from the album Da Capo | ||||

| B-side | "No. Fourteen" | |||

| Released | July 1966 | |||

| Recorded | June 17 and 20, 1966 | |||

| Studio | Sunset Sound Recorders, Hollywood, California | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 2:15 | |||

| Label | Elektra | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Arthur Lee | |||

| Producer(s) | Jac Holzman | |||

| Love singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"7 and 7 Is" is a song written by Arthur Lee and recorded by his band Love on June 17 and 20, 1966, at Sunset Sound Recorders in Hollywood. It was produced by Jac Holzman and engineered by Bruce Botnick.

The song was released as the A-side of Elektra single 45605 in July, 1966. The B-side was "No. Fourteen", an outtake from the band's earlier recordings. "7 and 7 Is" made the Billboard Pop Singles chart on July 30, 1966, peaking at number 33 during a ten-week chart run and becoming the band's highest-charting hit single. The recording also featured on the band's second album, Da Capo.

Background and development

[edit]Arthur Lee wrote "7 and 7 Is" at the Colonial Apartments on Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood.[2] The song was inspired by his high school girlfriend Anita "Pretty" Billings, with whom he shared a birthday of March 7.[3][nb 1] Describing how the song came to him, Lee stated: "I was living on Sunset and woke up early one morning. The whole band was asleep. I went in the bathroom, and I wrote those words. My songs used to come to me just before dawn, I would hear them in dreams, but if I didn't get up and write them down, or if I didn't have a tape recorder to hum into, I was through. If I took for granted that I could remember it the next day—boink, it was gone."[5] The lyrics describe Lee's frustration at teenage life—the reference to "in my lonely room I'd sit, my mind in an ice cream cone" being to wearing (in reality or metaphorically) a dunce's cap.[6]

Lee's original version of the song was a slow folk song in the style of Bob Dylan.[2] Its arrangement developed as the band experimented in the studio.[7] Bassist Ken Forssi had received a bass fuzz effect unit from an endorsement deal the band had signed with Vox, and Lee suggested Forssi use it on "7 and 7 Is". Lead guitarist Johnny Echols recalled: "We started playing [with it] and at first it sounded strange, but Kenny started doing this sliding bass thing with it. As we played it we could hear that this was something different, something new."[8]

Recording

[edit]Love recorded "7 and 7 Is" on June 17 and 20, 1966, at Sunset Sound Recorders,[9] with Jac Holzman producing and Bruce Botnick engineering.[10] The fuzz bass was ultimately abandoned as it overpowered the other instruments, but Forssi was able to achieve a similar sound with the feedback caused by his semi-acoustic Eko bass. Echols also used feedback, as well as extensive reverb and tremolo,[11] saying he had wanted to use a surf guitar effect in a different context.[9]

The sessions were tumultuous due to the song's fast and intense drum part, with Lee and drummer Alban "Snoopy" Pfisterer taking turns trying to accomplish it. Pfisterer later said: "The session was a nightmare ... I had blisters on my fingers. I don't know how many times I tried to play that damn thing and it just wasn't coming out. Arthur would try it; then I'd try it. Finally I got it. He couldn't do it."[12] Echols praised it as Pfisterer's best performance.[11] Estimates in the number of takes the song required range from 20 to 60;[13] however, most of these were only false starts.[9] The song took 4 hours to record according to Echols, who also claimed that the session took longer due to Holzman and Botnick objecting to the band's experimentation: "they kept stopping us, saying, 'It's feeding back!' We'd say, 'It's supposed to feed back.'"[14]

In what has been called a "flirtation" with musique concrète,[15] the track climaxes with the sound of an atomic explosion before a peaceful conclusion, in a blues form, which then fades out.[6] Botnick said the explosion was taken from a sound effects record and may have been a gunshot slowed down. During live performances, Echols would recreate the sound by kicking his amplifier with the reverb turned all the way up.[16]

Release and reception

[edit]Elektra Records issued "7 and 7 Is" in July 1966, backed with "No. Fourteen", an outtake from Love's debut album.[17] It entered the Billboard Hot 100 on July 30 and spent 10 weeks on the chart, peaking at number 33 on September 24.[18] It was the highest-charting single of the band's career.[16] Elektra released the band's second album, Da Capo, in November,[19] with "7 and 7 Is" sequenced as the fourth track, between "¡Que Vida!" and "The Castle".[20]

Music critic Robert Christgau called the song "a perfect rocker".[21] Cash Box described the song as a "pulsating, rhythmic extremely danceable blueser with a clever gimmick wind-up".[22]

Covers

[edit]Described as garage rock[23] and proto-punk,[24] the song was later covered by numerous bands, most notably The Ramones, Alice Cooper, Jared Louche and The Aliens,[25] The Electric Prunes, Billy Bragg, The Sidewinders, The Fuzztones, Robert Plant, Rush, Alice Bag, The Bangles, Deep Purple, and Hollywood Vampires as well as a re-recording by Lee himself.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Billings had also inspired Lee's songs "My Diary" (recorded by Rosa Lee Brooks) and "A Message to Pretty" from Love's self-titled debut album.[4]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Stanley, Bob (13 September 2013). "The Golden Road: San Francisco and Psychedelia". Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story of Modern Pop. Faber & Faber. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-571-28198-5.

- ^ a b Sandoval 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Einarson 2010, pp. 52, 116; Bronson, Gallo & Sandoval 1995, p. 15.

- ^ Einarson 2010, p. 52.

- ^ Bronson, Gallo & Sandoval 1995, p. 15.

- ^ a b Hoskyns 2002, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Einarson 2010, pp. 116–117; Sandoval 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Einarson 2010, p. 116.

- ^ a b c Sandoval 2002, p. 4.

- ^ Einarson 2010, pp. 116, 118.

- ^ a b Einarson 2010, p. 117.

- ^ Einarson 2010, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Einarson 2010, p. 117: 20; Brooks 1997, p. 35: 60.

- ^ Einarson 2010, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Pouncey 2002, p. 157.

- ^ a b Einarson 2010, p. 118.

- ^ Bronson, Gallo & Sandoval 1995, p. 29.

- ^ "Chart History: Love". Billboard. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Einarson 2010, p. 145.

- ^ Brooks 1997, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Christgau, R. (June 1967). "Columns". Esquire. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ "CashBox Record Reviews" (PDF). Cash Box. July 16, 1966. p. 36. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie (2014). Jingle Jangle Morning: Folk-Rock in the 1960s. BookBaby. ISBN 978-0-9915892-1-0.

- ^ Schinder, S. & Schwartz, A. (2008). Icons of Rock. ABC-CLIO. p. 263. ISBN 9780313338465.

- ^ Steininger, Alex (July 30, 2020). "Jared Louche and the Aliens: Covergirl". In Music We Trust (26). Retrieved July 30, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Bronson, Harold; Gallo, Phil; Sandoval, Andrew (1995). Love Story 1966-1972 (PDF) (Liner notes). Love. Rhino Records. R2 73500.

- Brooks, Ken (1997). Arthur Lee: Love Story. Andover, Hampshire: Agenda Books. ISBN 1-899882-60-X.

- Einarson, John (2010). Forever Changes: Arthur Lee and the Book of Love. London: Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-31-2.

- Hoskyns, Barney (2002). Arthur Lee: Alone Again Or. Edinburgh: Mojo Books. ISBN 978-1-84195-315-1.

- Pouncey, Edwin (2002). "Rock Concrète". In Young, Rob (ed.). Undercurrents: The Hidden Wiring of Modern Music. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 153–162. ISBN 978-0-8264-6450-7.

- Sandoval, Andrew (2002). Da Capo (Liner Notes). Love. Carlin Music Corporation. 8122 73604-2.