North American Free Trade Agreement: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 206.78.50.75 to last revision by Snigbrook (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''North American Free Trade Agreement''' ('''NAFTA''' |

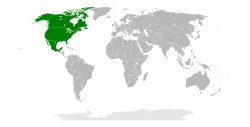

The '''North American Free Trade Agreement''' ('''NAFTA''') is a trilateral [[trade bloc]] in North America created by the governments of the United States, Canada, and Mexico. It superseded the [[Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement]] between the US and Canada. |

||

Following diplomatic negotiations dating back to 1991 between the three nations, the leaders meet in San Antonio, Texas on December 17, 1992 to sign NAFTA. U.S. President [[George H.W. Bush]], Canadian Prime Minister [[Brian Mulroney]] and Mexico's President [[Carlos Salinas]], each responsible for spearheading and promoting the agreement, ceremonially signed it. The agreement needed to be ratified by each nation's legislative or parliamentary branch before it could actually become law. In the U.S., Bush, who had worked to "fast track" the signing prior to the end of his term, ran out of time and had to pass the required ratification and "signing into law" to incoming president [[Bill Clinton]]. Prior to sending it to the House of Representatives, Clinton introduced clauses intended to protect American workers and allay the concerns of many House representatives. It also required U.S. partners to adhere to environmental practices and regulations similar to its own. The ability to enforce these clauses, especially with Mexico, was considered questionable, and with much consternation and emotional discussion the House of Representatives approved NAFTA on November 17, 1993, by a vote of 234 to 200. Remarkably, the agreement's supporters included 132 Republicans and only 102 Democrats. That unusual combination reflected the challenges President Clinton faced in convincing Congress that the controversial piece of legislation would truly benefit all Americans. The agreement was signed into law in the U.S. on December 8, 1993 by President Bill Clinton and went into effect on January 1, 1994.<ref>http://millercenter.org/academic/americanpresident/events/12_08</ref><ref>http://www.fina-nafi.org/eng/integ/chronologie.asp?langue=eng&menu=integ</ref><ref>http://www.globalohio.org/NAFTA/Nafta.htm</ref><ref>http://www.texaspolicy.com/printable.php?report_id=244</ref><ref>http://www.pollutionissues.com/Li-Na/NAFTA-North-American-Free-Trade-Agreement.html</ref> |

Following diplomatic negotiations dating back to 1991 between the three nations, the leaders meet in San Antonio, Texas on December 17, 1992 to sign NAFTA. U.S. President [[George H.W. Bush]], Canadian Prime Minister [[Brian Mulroney]] and Mexico's President [[Carlos Salinas]], each responsible for spearheading and promoting the agreement, ceremonially signed it. The agreement needed to be ratified by each nation's legislative or parliamentary branch before it could actually become law. In the U.S., Bush, who had worked to "fast track" the signing prior to the end of his term, ran out of time and had to pass the required ratification and "signing into law" to incoming president [[Bill Clinton]]. Prior to sending it to the House of Representatives, Clinton introduced clauses intended to protect American workers and allay the concerns of many House representatives. It also required U.S. partners to adhere to environmental practices and regulations similar to its own. The ability to enforce these clauses, especially with Mexico, was considered questionable, and with much consternation and emotional discussion the House of Representatives approved NAFTA on November 17, 1993, by a vote of 234 to 200. Remarkably, the agreement's supporters included 132 Republicans and only 102 Democrats. That unusual combination reflected the challenges President Clinton faced in convincing Congress that the controversial piece of legislation would truly benefit all Americans. The agreement was signed into law in the U.S. on December 8, 1993 by President Bill Clinton and went into effect on January 1, 1994.<ref>http://millercenter.org/academic/americanpresident/events/12_08</ref><ref>http://www.fina-nafi.org/eng/integ/chronologie.asp?langue=eng&menu=integ</ref><ref>http://www.globalohio.org/NAFTA/Nafta.htm</ref><ref>http://www.texaspolicy.com/printable.php?report_id=244</ref><ref>http://www.pollutionissues.com/Li-Na/NAFTA-North-American-Free-Trade-Agreement.html</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:54, 23 March 2009

North American Free Trade Agreement | |

|---|---|

| |

| Secretariats | Mexico City, Ottawa and Washington, D.C. |

| Official languages | English,Spanish,French |

| Membership | |

| Establishment | |

• Formation | January 1, 1994 |

| Area | |

• Total | 21,783,850 km2 (8,410,790 sq mi) (1st) |

• Water (%) | 7.4 |

| Population | |

• 2008 estimate | 445,335,091 (3rd) |

• Density | 20.4/km2 (52.8/sq mi) (195th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2008 (IMF) estimate |

• Total | $17,153 trillion (n/a) |

• Per capita | $35,491 (n/a) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2008 (IMF) estimate |

• Total | $16,792 trillion (n/a) |

• Per capita | $35,564 (18th) |

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) is a trilateral trade bloc in North America created by the governments of the United States, Canada, and Mexico. It superseded the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement between the US and Canada.

Following diplomatic negotiations dating back to 1991 between the three nations, the leaders meet in San Antonio, Texas on December 17, 1992 to sign NAFTA. U.S. President George H.W. Bush, Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Mexico's President Carlos Salinas, each responsible for spearheading and promoting the agreement, ceremonially signed it. The agreement needed to be ratified by each nation's legislative or parliamentary branch before it could actually become law. In the U.S., Bush, who had worked to "fast track" the signing prior to the end of his term, ran out of time and had to pass the required ratification and "signing into law" to incoming president Bill Clinton. Prior to sending it to the House of Representatives, Clinton introduced clauses intended to protect American workers and allay the concerns of many House representatives. It also required U.S. partners to adhere to environmental practices and regulations similar to its own. The ability to enforce these clauses, especially with Mexico, was considered questionable, and with much consternation and emotional discussion the House of Representatives approved NAFTA on November 17, 1993, by a vote of 234 to 200. Remarkably, the agreement's supporters included 132 Republicans and only 102 Democrats. That unusual combination reflected the challenges President Clinton faced in convincing Congress that the controversial piece of legislation would truly benefit all Americans. The agreement was signed into law in the U.S. on December 8, 1993 by President Bill Clinton and went into effect on January 1, 1994.[1][2][3][4][5]

In terms of combined purchasing power parity GDP of its members, as of 2007[update] the trade block is the largest in the world and second largest by nominal GDP comparison. It is also one of the most powerful, wide-reaching treaties in the world.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has two supplements, the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC) and the North American Agreement on Labour Cooperation (NAALC).

Effects

The effects of NAFTA, both positive and negative, have been quantified by several economists, whose findings have been reported in publications such as the World Bank's Lessons from NAFTA for Latina America and the Caribbean,[6] NAFTA's Impact on North America,[7] and NAFTA Revisited by the Institute for International Economics.[8] Some argue that NAFTA has been positive for Mexico, which has seen its poverty rates fall and real income rise (in the form of lower prices, especially food), even after accounting for the 1994–1995 economic crisis.[9] Others argue that NAFTA has been beneficial to business owners and elites in all three countries, but has had negative impacts on farmers in Mexico who saw food prices fall based on cheap imports from U.S. agribusiness, and negative impacts on U.S. workers in manufacturing and assembly industries who lost jobs. Critics also argue that NAFTA has contributed to the rising levels of inequality in both the U.S. and Mexico. Some economists believe that NAFTA has not been enough (or worked fast enough) to produce an economic convergence,[10] nor to substantially reduce poverty rates. Some have suggested that in order to fully benefit from the agreement, Mexico must invest more in education and promote innovation in infrastructure and agriculture. Many Americans disapprove of this agreement and there have been, so far, ineffective efforts to get the trade bloc removed.

Trade

According to Isaac (2005), overall, NAFTA has not caused trade diversion, aside from a few industries such as textiles and apparel, in which rules of origin negotiated in the agreement were specifically designed to make U.S. firms prefer Mexican manufacturers. The World Bank also showed that the combined percentage growth of NAFTA imports was accompanied by an almost similar increase of non-NAFTA exports.

Industry

Maquiladoras (Mexican factories which take in imported raw materials and produce goods for export) have become the landmark of trade in Mexico. These are plants that moved to this region from the United States, hence the debate over the loss of American jobs. Hufbauer's (2005) book shows that income in the maquiladora sector has increased 15.5% since the implementation of NAFTA in 1994. Other sectors now benefit from the free trade agreement, and the share of exports from non-border states has increased in the last five years while the share of exports from maquiladora-border states has decreased. This has allowed for the rapid growth of non-border metropolitan areas, such as Toluca, León and Puebla; all three larger in population than Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, and Reynosa. The main non-maquiladora industry that has benefited from NAFTA is the automobile industry.

Environment

Securing US congressional approval for NAFTA would have been impossible without addressing public concerns about NAFTA’s environmental impact. The Clinton Administration negotiated a side agreement on the environment with Canada and Mexico, the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation, NAAEC, which led to the creation of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation in 1994. To alleviate concerns that NAFTA, the first regional trade agreement between a developing country and two developed countries, would have negative environmental impacts, the CEC was given a mandate to conduct ongoing ex post environmental assessment of NAFTA.[11]

In response to this mandate, the CEC created a framework for conducting environmental analysis of NAFTA, one of the first ex post frameworks for the environmental assessment of trade liberalization. The framework was designed to produce a focused and systematic body of evidence with respect to the initial hypotheses about NAFTA and the environment, such as the concern that NAFTA would create a “race to the bottom” in environmental regulation among the three countries, or the hope that NAFTA would pressure governments to increase their environmental protection mechanisms.[12] The CEC has held four symposia using this framework to evaluate the environmental impacts of NAFTA and has commissioned 47 papers on this subject. In keeping with the CEC’s overall strategy of transparency and public involvement, the CEC commissioned these papers from leading independent experts.[13]

Overall, none of the initial hypotheses were confirmed. NAFTA did not inherently present a systemic threat to the North American environment, as was originally feared, but NAFTA-related environmental threats instead occurred in specific areas where government environmental policy, infrastructure, or mechanisms, were unprepared for the increasing scale of production under trade liberalization. In some cases, environmental policy was neglected in the wake of trade liberalization; in other cases, NAFTA’s measures for investment protection, such as Chapter 11, and measures against non-tariff trade barriers, threatened to discourage more vigorous environmental policy.[14] The most serious overall increases in pollution due to NAFTA were found in the base metals sector, the Mexican petroleum sector, and the transportation equipment sector in the United States and Mexico, but not in Canada.[15]

Agriculture

From the earliest negotiation, agriculture was (and still remains) a controversial topic within NAFTA, as it has been with almost all free trade agreements that have been signed within the WTO framework. Agriculture is the only section that was not negotiated trilaterally; instead, three separate agreements were signed between each pair of parties. The Canada-U.S. agreement contains significant restrictions and tariff quotas on agricultural products (mainly sugar, dairy, and poultry products), whereas the Mexico-U.S. pact allows for a wider liberalization within a framework of phase-out periods (it was the first North-South FTA on agriculture to be signed).

The overall effect of the Mexico-U.S. agricultural agreement is a matter of dispute. Mexico did not invest in the infrastructure necessary for competition, such as efficient railroads and highways, creating more difficult living conditions for the country's poor. Still, the causes of rural poverty cannot be directly attributed to NAFTA; in fact, Mexico's agricultural exports increased 9.4 percent annually between 1994 and 2001, while imports increased by only 6.9 percent a year during the same period.[16]

Production of corn in Mexico has increased since NAFTA's implementation. However, internal corn demand has increased beyond Mexico's sufficiency, and imports have become necessary, far beyond the quotas Mexico had originally negotiated.[17] Zahniser & Coyle have also pointed out that corn prices in Mexico, adjusted for international prices, have drastically decreased, yet through a program of direct income transfer (a subsidy) expanded by former president Vicente Fox, production has remained stable since 2000.[18]

The logical result of a lower commodity price is that more use of it is made downstream. Unfortunately, many of the same rural people who would have been likely to produce higher-margin value-added products in Mexico have instead emigrated. The rise in corn prices due to increased ethanol demand may improve the situation of corn farmers in Mexico.

In a study published in the August 2008 issue of the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, NAFTA has increased U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico and Canada even though most of this increase occurred a decade after its ratification. The study focused on the effects that gradual "phase-in" periods in regional trade agreements, including NAFTA, have on trade flows. Most of the increase in members’ agricultural trade, which was only recently brought under the purview of the World Trade Organization, was due to very high trade barriers before NAFTA or other regional trade agreements.[19]

Mobility of persons

According to the Department of Homeland Security Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, during fiscal year 2006 (i.e., October 2005 through September 2006), 74,098 foreign professionals (64,633 Canadians and 9,247 Mexicans) were admitted into the United States for temporary employment under NAFTA (i.e., in the TN status). Additionally, 17,321 of their family members (13,136 Canadians, 2,904 Mexicans, as well as a number of third-country nationals married to Canadians and Mexicans) entered the U.S. in the treaty national's dependent (TD) status.[20] Because DHS counts the number of the new I-94 arrival records filled at the border, and the TN-1 admission is valid for one year, the number of non-immigrants in TN status present in the U.S. at the end of the fiscal year is approximately equal to the number of admissions during the year. (A discrepancy may be caused by some TN entrants leaving the country or changing status before their one-year admission period expired, while other aliens admitted earlier may change their status to TN or TD, or extend earlier granted TN status).

Canadian authorities estimated that, as of December 1, 2006, the total of 24,830 U.S. citizens and 15,219 Mexican citizens were present in Canada as "foreign workers". These numbers include both entrants under the NAFTA agreement and those who have entered under other provisions of the Canadian immigration law.[21] New entries of foreign workers in 2006 were 16,841 (U.S. citizens) and 13,933 (Mexicans).[22]

Criticism and controversies

Canadian disputes

There is much concern in Canada over the provision that if something is sold even once as a commodity, the government cannot stop its sale in the future.[23] This applies to the water from Canada's lakes and rivers, fueling fears over the possible destruction of Canadian ecosystems and water supply.

Other fears come from the effects NAFTA has had on Canadian lawmaking. In 1996, the gasoline additive MMT was brought into Canada by an American company. At the time, the Canadian federal government banned the importation of the additive. The American company brought a claim under NAFTA Chapter 11 seeking US$201 million,[24] and by Canadian provinces under the Agreement on Internal Trade ("AIT"). The American company argued that their additive had not been conclusively linked to any health dangers, and that the prohibition was damaging to their company. Following a finding that the ban was a violation of the AIT,[25] the Canadian federal government repealed the ban and settled with the American company for US$13 million.[26] Studies by Health and Welfare Canada (now Health Canada) on the health effects of MMT in fuel found no significant health effects associated with exposure to these exhaust emissions. Other Canadian researchers and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency disagree with Health Canada, and cite studies that include possible nerve damage.[27]

The United States and Canada had been arguing for years over the United States' decision to impose a 27 percent duty on Canadian softwood lumber imports, until new Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper compromised with the United States and reached a settlement on July 1, 2006.[28] The settlement has not yet been ratified by either country, in part due to domestic opposition in Canada.

Canada had filed numerous motions to have the duty eliminated and the collected duties returned to Canada.[29] After the United States lost an appeal from a NAFTA panel, it responded by saying "We are, of course, disappointed with the [NAFTA panel's] decision, but it will have no impact on the anti-dumping and countervailing duty orders." (Nick Lifton, spokesman for U.S. Trade Representative Rob Portman)[30] On July 21, 2006, the U.S. Court of International Trade found that imposition of the duties was contrary to U.S. law.[31][32]

Canadian government challenged on change in Income trust taxation

On October 30, 2007, American citizens Marvin and Elaine Gottlieb filed a Notice of Intent to Submit a Claim to Arbitration under NAFTA. The couple claims thousands of U.S. investors lost a total of $5 billion dollars in the fall-out from the Conservative Government's decision last year to effectively tax income trusts in the energy sector out of existence.

Under the NAFTA, Canada is not allowed to target other NAFTA citizens when they impose new measures. Canadian Federal Finance Minister Jim Flaherty is on record that energy trusts were included because of their high U.S. ownership, while Real Estate Investment Trusts, owned mostly by Canadians, were excluded. NAFTA also stipulates that Canada must pay compensation for destroying investment by U.S. investors. The Government of Canada's 2006 Halloween tax changes for income trusts were designed to eliminate the income trust model for investment by U.S. citizens. The NAFTA says that U.S. investors are entitled to rely upon Canadian government promises. Harper repeatedly made a public promise that his Government would not tax trusts, as had the previous Liberal Government. Canada's tax treaty with the United States also says that trust income will not be taxed at more than 15 percent.

The Gottliebs maintain a website for American and Mexican citizens interested in filing a NAFTA claim against the Government of Canada.[33]

U.S. Deindustrialization

An increase in domestic manufacturing output and a proportionally greater domestic investment in manufacturing does not necessarily mean an increase in domestic manufacturing jobs; this increase may simply reflect greater automation and higher productivity. Although the U.S. total civilian employment may have grown by almost 15 million in between 1993 and 2001, manufacturing jobs only increased by 476,000 in the same time period.[34] Furthermore from 1994 to 2007, net manufacturing employment has declined by 3,654,000, and during this period several other free trade agreements have been concluded or expanded.[34]

Impact on Mexican farmers

In 2000, U.S. government subsidies to the corn sector totaled $10.1 billion, a figure ten times greater than the total Mexican agricultural budget that year.[35] Other studies reject NAFTA as the force responsible for depressing the incomes of poor corn farmers, citing the trend's existence more than a decade before NAFTA's existence, an increase in maize production after NAFTA went into effect in 1994, and the lack of a measurable impact on the price of Mexican corn due to subsidized corn coming into Mexico from the United States, though they agree that the abolition of U.S. agricultural subsidies would benefit Mexican farmers.[36]

Chapter 11

Another contentious issue is the impact of the investment obligations contained in Chapter 11 of the NAFTA.[37] Chapter 11 allows corporations or individuals to sue Mexico, Canada or the United States for compensation when actions taken by those governments (or by those for whom they are responsible at international law, such as provincial, state, or municipal governments) have adversely affected their investments.

This chapter has been invoked in cases where governments have passed laws or regulations with intent to protect their constituents and their resident businesses' profits. Language in the chapter defining its scope states that it cannot be used to "prevent a Party from providing a service or performing a function such as law enforcement, correctional services, income security or insurance, social security or insurance, social welfare, public education, public training, health, and child care, in a manner that is not inconsistent with this Chapter."[38]

This chapter has been criticized by groups in the U.S.,[39] Mexico,[40] and Canada[41] for a variety of reasons, including not taking into account important social and environmental[42] considerations. In Canada, several groups, including the Council of Canadians, challenged the constitutionality of Chapter 11. They lost at the trial level,[43] and have subsequently appealed.

Methanex, a Canadian corporation, filed a US$970 million suit against the United States, claiming that a California ban on MTBE, a substance that had found its way into many wells in the state, was hurtful to the corporation's sales of methanol. However, the claim was rejected, and the company was ordered to pay US$3 million to the U.S. government in costs.[44]

In another case, Metalclad, an American corporation, was awarded US$15.6 million from Mexico after a Mexican municipality refused a construction permit for the hazardous waste landfill it intended to construct in Guadalcázar, San Luis Potosí. The construction had already been approved by the federal government with various environmental requirements imposed (see paragraph 48 of the tribunal decision). The NAFTA panel found that the municipality did not have the authority to ban construction on the basis of the alleged environmental concerns.[45]

Chapter 19

Also contentious is NAFTA's Chapter 19, which subjects antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) determinations with binational panel review instead of, or in addition to, conventional judicial review. For example, in the United States, review of agency decisions imposing antidumping and countervailing duties are normally heard before the U.S. Court of International Trade, an Article III court. NAFTA parties, however, have the option of appealing the decisions to binational panels composed of five citizens from the two relevant NAFTA countries. The panelists are generally lawyers experienced in international trade law. Since the NAFTA does not include substantive provisions concerning AD/CVD, the panel is charged with determining whether final agency determinations involving AD/CVD conform with the country's domestic law. Chapter 19 can be considered as somewhat of an anomaly in international dispute settlement since it does not apply international law, but requires a panel composed of individuals from many countries to reexamine the application of one country's domestic law.

A Chapter 19 panel is expected to examine whether the agency's determination is supported by "substantial evidence." This standard assumes significant deference to the domestic agency.

Some of the most controversial trade disputes in recent years, such as the U.S.-Canada softwood lumber dispute, have been litigated before Chapter 19 panels.

Decisions by Chapter 19 panels can be challenged before a NAFTA extraordinary challenge committee. However, an extraordinary challenge committee does not function as an ordinary appeal. Under the NAFTA, it will only vacate or remand a decision if the decision involves a significant and material error that threatens the integrity of the NAFTA dispute settlement system. As of January 2006[update], no NAFTA party has successfully challenged a Chapter 19 panel's decision before an extraordinary challenge committee.

Chapter 20

Chapter 20 provides a procedure for the interstate resolution of disputes over the application and interpretation of the NAFTA. It was modeled after Chapter 18 of the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement.[46]

Chapter 14

"This chapter dealing with Financial Services provides for the same procedure as Chapter 20, except that the members of the panel shall be selected from a roster of fifteen persons who "have expertise in financial services law or practice..." The roster has never been made public and no dispute has yet occurred under this chapter."[47]

See also

- Canada-Mexico relations

- Canada-United States relations

- Independent Task Force on North America

- Mexico–United States relations

- North American Competitiveness Council

- North American Currency Union (Amero)

- North American Forum on Integration

- North American SuperCorridor Coalition

- North American Union

- Consortium for North American Higher Education Collaboration

References

- ^ http://millercenter.org/academic/americanpresident/events/12_08

- ^ http://www.fina-nafi.org/eng/integ/chronologie.asp?langue=eng&menu=integ

- ^ http://www.globalohio.org/NAFTA/Nafta.htm

- ^ http://www.texaspolicy.com/printable.php?report_id=244

- ^ http://www.pollutionissues.com/Li-Na/NAFTA-North-American-Free-Trade-Agreement.html

- ^ Lederman D, W Maloney and L Servén (2005) Lessons from NAFTA for Latin America and the Caribbean: Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, USA

- ^ Weintraub S (2004), NAFTA's Impact on North America The First Decade, CSIS Press: Washington, USA

- ^ Hufbauer GC and Schott, JJ, NAFTA Revisited, Institute for International Economics, Washington D.C. 2005

- ^ "THE ORIGIN OF MEXICO'S 1994 FINANCIAL CRISIS". Cato.org. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ Floudas, Demetrius Andreas & Rojas, Luis Fernando; "Some Thoughts on NAFTA and Trade Integration in the American Continent", 52 (2000) International Problems 371

- ^ IngentaConnect NAFTA Commission for Environmental Cooperation: ongoing assessmen

- ^ http://www.cec.org/programs_projects/trade_environ_econ/pdfs/frmwrk-e.pdf

- ^ "Trade and Environment in the Americas". Cec.org. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ "IngentaConnect NAFTA Commission for Environmental Cooperation: ongoing assessment of trade liberalization in North America". Ingentaconnect.com. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ http://www.cec.org/programs_projects/trade_environ_econ/pdfs/Reinert.pdf

- ^ Greening the Americas, Carolyn L. Deere (editor). MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

- ^ Template:PDFlink p. 4

- ^ U.S.-Mexico Corn Trade During the NAFTA Era: New Twists to an Old Story USDA Economic Research Service

- ^ Newswise: Free Trade Agreement Helped U.S. Farmers Retrieved on June 12, 2008.

- ^ DHS Yearbook 2006. Supplemental Table 1: Nonimmigrant Admissions (I-94 Only) by Class of Admission and Country of Citizenship: Fiscal Year 2006

- ^ [http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/statistics/facts2006/temporary/04.asp Facts and Figures 2006 Immigration Overview: Temporary Residents] (Citizenship and Immigration Canada)

- ^ "Facts and Figures 2006 - Immigration Overview: Permanent and Temporary Residents". Cic.gc.ca. 2007-06-29. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ The Council of Canadians: Water

- ^ Template:PDFlink, 'Ethyl Corporation vs. Government of Canada'

- ^ Template:PDFlink

- ^ Dispute Settlement

- ^ MMT: the controversy over this fuel additive continues

- ^ U.S., Canada Reach Final Agreement on Lumber Dispute

- ^ softwood Lumber

- ^ Statement from USTR Spokesperson Neena Moorjani Regarding the NAFTA Extraordinary Challenge Committee decision in Softwood Lumber

- ^ Template:PDFlink

- ^ Statement by USTR Spokesman Stephen Norton Regarding CIT Lumber Ruling

- ^ NAFTA Trust Claims

- ^ a b "U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics".

- ^ Oxfam (2003). "Dumping without Borders: How U.S. Agricultural Policies Are Destroying the Livelihoods of Mexican Corn Farmers" (PDF). Oxfam. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fiess, Norbert (2004-11-24). "Mexican Corn: The Effects of NAFTA" (PDF). Trade Note. 18. The World Bank Group. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ NAFTA, Chapter 11

- ^ http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/etext93/naftchap.txt

- ^ 'North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)', Public Citizen

- ^ Red Mexicana de Accion Frente al Libre Comercio. "NAFTA and the Mexican Environment". Archived from the original on 2006-05-21.

- ^ The Council of Canadians

- ^ The NAFTA environmental agreement: The Intersection of Trade and the Environment

- ^ Judge Rebuffs Challenge to NAFTA'S Chapter 11 Investor Claims Process

- ^ Template:PDFlink

- ^ Template:PDFlink

- ^ Gantz, D.A. 1999. “Dispute Settlement Under the NAFTA and the WTO:Choice of Forum Opportunities and Risks for the NAFTA Parties.” American University International Law Review 14(4):1025–1106.

- ^ de Mestral, A. 2005. “NAFTA Dispute Settlement: Creative Experiment or Confusion.” Unpublished manuscript, McGill University, Montreal, QC .

External links

Official

- NAFTA Secretariat website

- NaftaNow.org - Jointly developed by the Governments of Canada, Mexico and the United States of America

- Office of the U.S. Trade Representative - NAFTA

- TradeAgreements.gov: an interagency effort by the United States Government to provide the public with the latest information on America's trade agreements

Text

News & Research

- Latin Business Chronicle NAFTA Turns 15: Bravo!

- Studies of the effects of NAFTA after 10 years have been prepared by both the U.S. Government (see NAFTA 10 Years Later) and the Canadian government (see NAFTA @10)

- The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, publishes annual economic statistics. The results of data mining research concerning NAFTA have been published on Centrerion Canadian Politics' NAFTA pages, the data having been mined from OECD sources.

- NAFTA at 10: An Economic and Foreign Policy Success by Daniel Griswold (December 17, 2002)

- Template:PDFlink (arguing that NAFTA Chapter 11 has more expansive compensation criteria than U.S. takings law, which has the potential to impact and threaten domestic environmental regulation and impact federalism issues)

- Immigration Flood Unleashed by NAFTA's Disastrous Impact on Mexican Economy

- David Bacon, "A Knife in the Heart

- Template:PDFlink

- From NAFTA to the SPP from Dollars & Sense magazine, January/February 2008

- How Has NAFTA Affected Trade and Employment? from Dollars & Sense magazine, January/February 2003

Websites

- North American Development Bank

- Public Citizen's Report on NAFTA

- Consortium for North American Higher Education Collaboration

- Border Trade Alliance

- Details of investor-state cases under NAFTA

- NAFTA Trust Claims

- NAFTA and World's hegemony

Further reading

- David Bacon. The Children of NAFTA: Labor wars on the U.S./Mexico Border. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2004. ISBN 0-520-23778-1.

- 1994 in Canada

- 1994 in Mexico

- 1994 in the United States

- Economy of North America

- History of the United States (1991–present)

- Modern Mexico

- Presidency of Bill Clinton

- United States-North American relations

- International organizations

- United States free trade agreements

- Canada free trade agreements

- Mexico free trade agreements