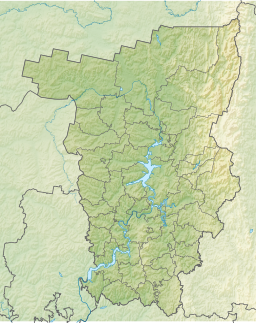

Pechora–Kama Canal

The Pechora–Kama Canal (Template:Lang-ru), or sometimes the Kama–Pechora Canal, was a proposed canal intended to link up the basin of the Pechora River in the north of European Russia with the basin of the Kama, a tributary of the Volga. An accomplishment of this project would integrate the Pechora into the system of waterways of European Russia, centered on the Volga – something that was of particular importance before the advent of the railways, or before the first railway reached the Pechora in the 1940s. Later on, the project was proposed mostly for the sake of transfer of Pechora's water to the Volga and further on to the Caspian Sea.

19th century proposals

In the 19th century, communication between the Kama and the Pechora was conducted mostly over a 40-km portage road between Cherdyn and Yaksha. There was also an option to use very small boats that could go up the uppermost reaches of Kama and Pechora tributaries, and cart the goods over the 4 km portage remaining. Poor river and road conditions made transportation into and out of the Pechora basin very expensive, and various improvement projects, including a narrow-gauge portage railroad were proposed. Nothing much was ever done, however.

20th century

A canal between the Pechora and the Kama was part of a plan for a "reconstruction of Volga and its basin", approved in November 1933 by a special conference of the USSR Academy of Sciences. Research in that direction was then conducted by Hydroproject, the dam and canal institute led by Sergey Yakovlevich Zhuk (Template:Lang-ru). Some design plans were developed by Zhuk's institute, but without either much publicity or actual construction work.[1]

The canal plan was given a new life in 1961 during Khrushchev's premiership. Now it was part of an even grander scheme for "Northern river reversal", which also included similar river water diversion projects in Siberia.

Nuclear test

Unlike most other parts of the grand river rerouting scheme, the Pechora to Kama route did not just stay on the drawing board. It saw actual on-the-ground work done of the most unusual kind: on March 23, 1971, three 15-kiloton underground nuclear charges were exploded near the village of Vasyukovo in Cherdynsky District of Perm Oblast, some 100 km (62 mi) north of the town of Krasnovishersk. This nuclear test, known as Taiga,[2] part of the Soviet peaceful nuclear explosions program, was intended to demonstrate the feasibility of using nuclear explosions for canal construction. The triple blast created a crater over 600 m (2,000 ft) long. Later on, it was decided that building an entire canal in this fashion, using potentially several hundreds of nuclear charges, would not be feasible, and the use of nuclear charges for canal excavation was abandoned.[3][4]

The Northern river reversal plan was completely abandoned by the government in 1986.

Environmental aftermath

| Taiga crater | |

|---|---|

| atomic lake | |

| Ядерное озеро (Russian) | |

| Coordinates | 61°18′21″N 56°35′55″E / 61.30583°N 56.59861°E |

| Part of | Pechora–Kama Canal |

| River sources | Beryozovka River (Perm Krai) |

| Built | March 23, 1971 |

| Max. length | 700 metres (2,300 ft) |

| Max. width | 350 metres (1,150 ft) |

The Taiga explosions may be among the devices that produced the highest proportion of their yield via fusion-only reactions, with 98% of their 15 kiloton explosive yield being derived from fusion reactions, a total fission fraction of 0.3 kilotons in a 15 kt device.[5][6] Such bombs are known as clean bombs, as it is fission that is responsible for generating radioactive fallout.

Around 2000, local environmentalists carried out several expeditions to the Taiga crater, and met the only person still residing in the Vasyukovo village. The fences surrounding the crater had rusted away and fallen down, and the "Atomic Lake" is now a popular fishing place for the residents of the other nearby villages, while its shores are known for the abundance of edible mushrooms. The area is also visited by the people who pick metal cables and other bits left over from the original test, to sell to scrap metal recycling businesses. The environmentalists recommended that the crater lake be fenced again, due to the continuing residual radioactivity.[7]

The triple "taiga" nuclear salvo test, part of the preliminary March 1971 Pechora–Kama Canal project, produced substantial amounts of relatively short-lived cobalt-60 from steel tubes and soil ("Origin of Co-60. Activation of stable Co, Fe, Ni (from the explosive device and the steel pipe, and from soil) by neutrons"). As of 2011, this fusion generated neutron activation product is responsible for about half of the gamma ray dose at the test site. Photosynthesizing vegetation exists all around the lake. A 2009 radiation survey of the lake and surrounding areas was conducted to determine the relative danger of the area,[8][9] finding "the current external γ-ray dose rate to a human from the contaminations associated with the 'Taiga' experiment was between 9 and 70 μSv [micro-Sieverts] per week". The report also recommended periodic monitoring of the site. In comparison, typical exposure from naturally occurring background radiation is about 3mSv per year, or 57μSv per week.[10]

See also

- Lake Chagan; a lake created as part of the Russian Peaceful Nuclear Explosions program

- Lake Karachay; a natural lake highly contaminated by the dumping of high-level nuclear waste

References

- ^ Weiner, Douglas R. (1999). A Little Corner of Freedom: Russian Nature Protection from Stalin to Gorbachev. University of California Press. p. 415. ISBN 0-520-23213-5.

- ^ The Soviet Taiga PNE

- ^ Soviet/Russian Nuclear Testing Summary

- ^ Pavel Podvig, ed. (2004). Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces. p. 478. ISBN 0-262-66181-0.

- ^ Disturbing the Universe – Freeman Dyson

- ^ The Soviet Program for Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Explosions by Milo D. Nordyke. Science & Global Security, 1998, Volume 7, pp. 1–117. See test shot "Taiga".

- ^ Атомный котлован (The Atomic Crater), Bellona, 25-Dec-2002

- ^ Ramzaev, V.; Repin, V.; Medvedev, A.; Khramtsov, E.; Timofeeva, M.; Yakovlev, V. (2011). "Radiological investigations at the "Taiga" nuclear explosion site: Site description and in situ measurements". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 102 (7): 672–680. doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2011.04.003. PMID 21524834.

- ^ Ramzaev, V.; Repin, V.; Medvedev, A.; Khramtsov, E.; Timofeeva, M.; Yakovlev, V. (2012). "Radiological investigations at the "Taiga" nuclear explosion site, part II: man-made γ-ray emitting radionuclides in the ground and the resultant kerma rate in air". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity. 109: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2011.12.009. PMID 22541991.

- ^ "Naturally-occurring "background" radiation exposure". radiologyinfo.org. Retrieved 28 July 2016.