Prognathodon

| Prognathodon Temporal range: Campanian - Maastrichtian,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| P. overtoni fossil at Royal Tyrrell Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Clade: | †Mosasauria |

| Family: | †Mosasauridae |

| Tribe: | †Prognathodontini |

| Genus: | †Prognathodon Dollo, 1889 |

| Type species | |

| Prognathodon solvayi Dollo, 1889

| |

| Other species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

(Williston, 1897)

| |

Prognathodon is an extinct genus of marine lizard belonging to the mosasaur family. It is classified as part of the Mosasaurinae subfamily, alongside genera like Mosasaurus and Clidastes. Prognathodon has been recovered from deposits ranging in age from the Campanian to the Maastrichtian in the Middle East, Europe, New Zealand, and North America.[1]

Prognathodon means "forejaw tooth", which originates from the Latin pro- ("earlier" or "prior"), Greek gnathos ("jaw") and odṓn ("tooth"). Twelve nominal species of Prognathodon are recognised, from North America, northern and western Africa, the Middle East, western Europe and New Zealand. Due to the sometimes clear differences between them and the incomplete nature of many of the specimens, the systematics of the genus and which species should properly be considered Prognathodon is controversial. Some species have been assigned to other genera, such as Dollosaurus and Brachysaurana, but this has also been questioned.

Prognathodon is known for its massively built jaws and teeth. Its distinct feeding adaptations have generated much interest in its ecology ever since its discovery, though direct evidence of its diet, such as gastric residues, is rare.[2]

Description

Prognathodon constitutes one of the largest-bodied mosasaur genera, with the largest known skull (belonging to P. currii) exceeding 140 cm in length. Despite its massive size, remains of the genus are often fragmentary and incomplete. To date, very few specimens are known with articulated skulls and none with an entire skeleton.[2] Though many species were large with sizes approaching or potentially exceeding 10 m (33 ft), such as P. currii, P. saturator and P. overtoni,[2] many species were considerably smaller in size. The type species, P. solvayi, was the smallest, barely reaching 5 m (16 ft) in length.[3] Considering the 2002 study from Christiansen & Bonde, the 2013 study presents that P. saturator could have reached 12 m (39 ft) in length, while Liodon sectorius (assigned as P. sectorius) reached 8 m (26 ft) in length.[4] In 2022, Gregory S. Paul proposed that P. overtoni reached 8 metres (26 ft) in length and 1 metric ton (1.1 short tons) in body mass, while P. currii reached 11 metres (36 ft) in length and 2.8 metric tons (3.1 short tons) in body mass.[5]

Other than its size and robust nature, another feature that defines Prognathodon is the form of the sclerotic rings, present in all species of the genus. The function of the scleral ossicles is to maintain the shape of the cornea and support the sclera in the region of Brucke's muscle responsible for affecting accommodation in the lacertilian eye. In the type species, P. solvayi, the sclerotic ring is only partially preserved, consisting of five scleral ossicles in each ring.[6] Similar sclerotic rings are seen in several other mosasaur genera, such as Mosasaurus.[7]

The latest published diagnosis for the genus Prognathodon was provided by Lingham-Soliar and Nolf (1989),[2] and states that the premaxilla lacks a rostrum anterior to the premaxillary teeth. The prefrontal forms a large portion of the posterolateral border of the external nares and the supraorbital wing with heavy triangular ala contacts the postorbitofrontal posteriorly over the orbit medial to the external edge of the frontal. The frontal does not emarginate above the orbits and a median dorsal ridge is either present or absent. The foramina on the parietal are small to moderately large, located anteromedially on a small prominence and are closely embraced on either side by short tongues from the frontal or located on the frontoparietal suture.[7]

The margins of the dorsal parietal surface are parallel to one another and the cranial midline to the posterior base of the diverging suspensorial rami, which forms a rectangular field medially on the parietal. The ventral process of the postorbitofrontal to jugal is indistinctly separated from the moderately well exposed dorsal surface of the postorbitofrontal and the ventroposterior process on the jugal is slightly developed to absent. The squamosal wing to the parietal is large. There is a deep groove present in the floor of the basioccipital for the basilar artery.[7]

The suprastapedial process is fused to the infrastapedial process on the quadrate and the tympanic ala are thick. The stapedial pit is nearly circular to elliptical in form. The posterior process on the dorsal surface of the dentary is present, incipient or absent and the dentary terminates abruptly in front of the first dentary tooth. The dentary itself contains thirteen to fourteen teeth and the pterygoid has seven to eight teeth. The medial wing from the coronoid contacts the angular, the anterior process on the coronoid abrupts over the surangular and makes contact with the posterior process of the dentary or ends with the surangular without contacting the dentary. The retroarticular process is rectangular in outline, medially inflected or laterally lacing. The marginal teeth are stout, bicarinate and smooth or striated. Zygosphenes and zygantra are absent, incipient or large and functional.[7]

Skull

Prognathodon is noted as having a very robust skull. The skull also shows adaptations towards a very powerful jaw musculature. The ratio between the length of the supratemporal fenestra and the total length of the skull has previously been used as an improvised measurement for mosasaur bite force, and is relatively high in Prognathodon (0.22 in P. overtoni and P. saturator) compared to other genera, such as Mosasaurus (0.19 in M. hoffmannii).[8]

The quadrates of Prognathodon, similarly to the genus Globidens, have fused suprastapedial and infrastapedial processes, which is possibly an adaptation to counteract the strong forces experienced by the bone during biting. Stong jaw musculature combined with a relatively short and tall dentary would have resulted in a very powerful bite.[9]

The skull of the type specimen of Prognathodon saturator is nearly complete, only lacking the anterior portion of the premaxilla and the dentaries. Though most of the anterior marginal teeth are missing, the inclination of the preserved roots suggest that P. saturator had procumbent teeth, a trait also seen in P. solvayi. The dorsal margin of the dentary is concave, whilst the ventral margin of the maxilla is slightly convex. The marginal teeth are massive, smooth and rounded as opposed to most other mosasaur teeth, which are typically facetted and laterally compressed. The mandible of P. saturator is very tall and massive, even more so than in other members of the genus. This is matched by the also massive pterygoid and various other portions of the skull, such as the temporal region and the braincase, which are all stout compared to other species in the genus.[9]

The type specimen of P. lutugini, whilst incomplete, preserves a significantly large portion of the skull. The specimen was originally stated to have preserved a small portion of the premaxilla, though D.V. Grigoriev (2013)[10] noted that said bone could at the moment not be located, and it is potentially missing. Both pterygoids were preserved, though the right one is at the moment almost entirely a restoration made of gypsum, with two original teeth. The left pterygoid was considerably more complete, but lacked all processes other than the basisphenoid process. The posterior alveolar margin was noted for being very small, with the teeth rising from a thin but pronounced vertical ridge. The ventral surface of the basisphenoid process is quite smooth and foramina are visible above the sixth tooth on the lateral surface of the pterygoid as well as above the position between the sixth and seventh teeth on the medial surface. The squamosal bone is only represented by a few fragments, but could be noted for being laterally compressed and tall, as in other species of Prognathodon. Its posteroventral surface is concave for contact with the quadrate. The dentaries are fused with the posterior end of the splenial and the anterior blade of the prearticular and have a tooth count of 13, with at least eight teeth possessing subdental crypts with some replacement teeth having been found in the type specimen. The subdental crypts are positioned postermodeially to the functional teeth. The coronoid is saddle-shaped and has a well-developed posterodorsal process, which gives the dorsal margin of said bone a nearly 110 degree angle between the horizontal anterior end and the subvertical posterior wing. This combination of characteristics aided in determining that P. lutugini was indeed a species of Prognathodon, since some researchers place it in a genus of its own, "Dollosaurus".[10]

Dentition

Species referred to Prognathodon are variable in terms of dentition. Robust and conical teeth with blunt, serrated carinae and smooth enamel are often seen as typical Prognathodon teeth and are routinely assigned to the genus. Despite this, the type species P. solvayi differs from this type of teeth and instead exhibits markedly labio-lingually compressed and gently facetted marginal teeth. There is also a certain degree of variation in tooth number, P. solvayi has 12 teeth on the maxilla and 13 on the dentary whilst P. overtoni has 14 dentary teeth.[7]

Of all species, P. solvayi has the most different teeth from other members of the genus. The tooth crowns are generally large and quite strongly striated and the anterior teeth are more procumbent than in any other mosasaurs. The premaxillary teeth are almost horizontal and the anterior dentary teeth only slightly less so. In addition to deep striae, the fragmentary material of P. solvayi reveals that the tooth crowns may also have been somewhat prismatic with seven to eight prisms on the external surface.[7]

Teeth of P. solvayi are more slender at the anterior end, broader and triangular towards the middle of the dental ramus, decreasing in size towards the posterior end with the last two teeth being rather stunted. The tooth crowns are only moderately inflated and in contrast to the teeth of P. overtoni, the teeth increase in size consistently in an antero-posterior direction and are somewhat less posteriorly recurved. In P. overtoni and other species (such as P. giganteus), the teeth are all fairly uniform in size other than the penultimate tooth base (which is larger).[7]

Another species noted for its divergent teeth is P. lutugini, where knowledge of the teeth mainly comes from isolated specimens. Known teeth are strongly bicarinate with a weak serration on both carinae. The carinae then divide the teeth into lingual and labial surfaces, with the lingual surface being more convex and large in comparison with the labial. The teeth have a slight posterior and medial recurvature and are noted for having smooth surfaces (which is different from other species of Prognathodon) except for minor wrinkles at the tips of the tooth crowns. The roots of the teeth are quite large at about 1.5 times the size of the tooth crowns and are barrel-shaped. The largest known tooth crowns are up to 5.5 cm tall and 2.5 cm wide at the base.[10]

The size of P. lutugini teeth also varies depending on the position in the mouth. Anterior pterygoid teeth are noted for being relatively large and comparable to the marginal teeth in size at up to 4.6 cm in height.[10]

A relatively small number of teeth in comparison to other mosasaurs (for an example, Prognathodon saturator preserves 14 teeth in the dentary, 12 in the maxilla and 6 in the pterygoid) is a characteristic present in all species of Prognathodon.[9]

Axial skeleton

Post-cranial fossils of Prognathodon are considerably rarer than skull material and isolated teeth.[2]

The type specimen of P. lutugini preserves several vertebrae. Four cervical vertebrae are preserved, which have well developed anterior and posterior zygapophyses. Functional zygosphenes and zygantra were found on two of the cervical vertebrae. Vertebral hypapophyseal peduncles were found on all four vertebrae and are very short and end as small laterally compressed oval facets. These facets are posteriorly inclined and located posteriorly on the ventral surfaces of the centra. The synapophyses are large, located anteriorly on the centra, and do not extend below the ventral margin of the centrum. The condyles and cotyles are weakly dorsoventrally compressed. The cervical vertebrae are almost the same size as the longest dorsal vertebrae and get to a length of about 7.2 cm and a height of 4 cm. 26 dorsal vertebrae are preserved in the specimen, though most are poorly preserved. Dorsal vertebrae are a little longer than the cervical and like the cervicals, the condyles and cotyles are weakly compressed dorsoventrally. The dorsal vertebrae are at a maximum about 8 cm in length and 5 cm in height. Additionally, the type specimen also preserved many rib fragments, though all incomplete. Two grooves run along the distal portion of the ribs from the articular head but only one groove remains behind the middle of the rib.[10]

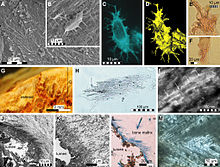

Soft tissue

The discovery of the exceptionally well-preserved specimen ERMNH HFV 197 from Maastrichtian deposits in Harrana, central Jordan allowed detailed examinations of unique details of the soft tissue morphology of Prognathodon. The fossil is not only largely complete and articulated, which is rare for Prognathodon specimens, but also preserves significant portions of the integument and a gentle bend on the last few caudal vertebrae. Most importantly, the fossil preserves the soft tissue outline of a tail fin. This helped in providing evidence that mosasaurs were convergent with ichthyosaurs, metriorhynchid thalattosuchians and whales in the evolution of a crescent-shaped tail fluke to aid in locomotion.[11]

The tail fluke is clearly asymmetric. The lower fin lobe follows the caudal vertebrae and would have had a streamlined cross-section in life, based on the proportions of the axial skeleton and the other soft tissues. The upper fin lobe is unsupported by the skeleton and is preserved as a small, almost wing-like, structure above the last few caudal vertebrae. The shape of the tail fluke is similar to that of the carcharhinid sharks, though turned upside down, with a small upper lobe and large lower lobe.[11]

The specimen also preserves scale impressions, particularly around the outline of the tail fluke. Though faint, these impressions reveal scales of "rhomboidal" shape.[11] Similarly shaped scales are present on the tail fluke of the well-preserved Platecarpus specimen LACM 128319.[12]

The proportions of the soft tissue structures and their relation to the skeletal elements of the specimen can be used to infer the shape and size of the fins in other species of Prognathodon and potentially in other mosasaur genera as well. In their description of the specimen, Lindgren et al. (2013)[11] noted that the specimen is strangely small by Prognathodon standards compared to some of the larger specimens in the genus. Thus, it was assumed that ERMNH HFV 197 was a juvenile specimen. That tail fin would grow to account for the increased weight of bigger individuals is rather logical, and can be observed in other groups that possess tail fins, such as extant sharks and extinct ichthyosaurs. For this reason, it is likely that adult Prognathodon, particularly of the larger species, would have had larger tail fins relative to their body size.[11] Lindgren et al. (2013) especially noted that the upper fin lobe likely would have grown to be proportionally larger in bigger individuals.[11]

History of discovery

Prognathodon was first described by Louis Dollo in 1889 based on specimens gathered in Belgium. There is some confusion over the correct generic name for the taxon. Dollo first mentioned the taxon as "Prognathodon" in some preliminary notes and provided a provisional diagnosis, but replaced the name Prognathodon with "Prognathosaurus" and used Prognathosaurus in all of his subsequent papers mentioning the genus.[7]

The first later use of "Prognathodon" was by Dale A. Russell in a comprehensive monograph on North American mosasaurs in 1967, where the priority of Prognathodon was made apparent. Russell also revised the species assigned to Prognathodon from North America , but only briefly commented on the Belgian specimens.[6]

Though the original remains of the genus were rather comprehensive and the original description was brief, no additional studies of the type material was done for a century. The lack of a comprehensive original description of the genus and the species referred to it from Belgium is strangely not unusual for mosasaur specimens discovered in the Craie de Ciply Formation of Belgium. Large amounts of work was commonly invested in extracting and mounting the specimens, but scientific study of them remained limited with diagnoses and descriptions mainly focusing on peculiar points of their anatomy, such as the quadrate and tympanic membrane of Plioplatecarpus houzeaui. Prognathodon giganteus, named by Dollo in 1904, is one of species with the most brief descriptions, apparently only intended to provide a name for the skeleton of the mosasaur for exhibition in the museum hall.[7]

The first comprehensive study of the Prognathodon specimens from Belgium (including the type specimen) was done by Theagarten Lingham-Soliar and Dirk Nolf in 1989[7] and the diagnosis in this study remains the latest published emended diagnosis for the genus.[2]

In 1998, an intact fossil skull was found in the Maastricht limestone quarries. Shortly after, it was nicknamed "Bèr", and put on display in the Maastricht Natural History Museum. This specimen was then identified as a Prognathodon, and received the species name Prognathodon saturator. This specimen was the first reasonably complete mosasaur specimen recovered from the Maastricht area since 1957; the skeleton is on display at the Natural History Museum at Maastricht, and is from an animal that was probably 12 metres long.[9]

A very large specimen found in Israel was for some time informally named "Oronosaurus", but eventually described as a new species of Prognathodon, P. currii.[13] Two specimens of Prognathodon overtoni described in 2011 from the early late Campanian (c. 74.5 Ma) Bearpaw Formation in Alberta, Canada provided the first fully articulated skeletons of the genus. Detailed studies of these and previously discovered specimens allowed several characters to be established that distinguishes Prognathodon from closely related genera like Liodon and long-snouted mosasaurines. The preserved teeth and gut contents also allowed studies into the inferred paleoecology of the genus.[2]

In 2009, Hani F. Kaddumi described the new species P. hudae based on a complete right dentary and partial left dentary from the Maastrichtian-age Muwaqqar Chalk Marl Formation of Harrana, Jordan. The specific name hudae honors Kaddumi's daughter Huda.[14] The new species and genus Tenerasaurus hashimi, also described by Kaddumi in 2009 from fossils likely belonging to a juvenile specimen, was reclassified as Prognathodon hashimi by Kaddumi, Johan Lindgren, and Michael J. Polcyn in 2013.[11]

A new fossil found in 2008 and described in 2013 belonging to a 1.8 m juvenile Prognathodon was found in Jordan's Harrana Site. The fossil was remarkable in that it preserved the outline of the mosasaur's tail fins, revealing that Prognathodon, like Platecarpus and later mosasaurs also had a bilobed tail fluke resembling a downturned shark's tail, the shape of which may have aided the creature in surfacing, as well as attacking prey. The discovery also lends evidence to the theory that later mosasaurs were even more well-adapted to the lifestyle first occupied by the ichthyosaurs.[11]

On September 19, 2012, it was announced that nine days earlier, again a skeleton of what appears to be a Mosasaur was found in the limestone quarry just outside Maastricht, the same quarry that yielded the type specimen of Mosasaurus hoffmanni. Carlo Brauer, an excavator operator at the ENCI quarry, discovered the teeth of the fossil in the shovel of his digger on Monday morning, September 10. In the days following the discovery, museum staff retrieved several large sections of the skull and part of the body and tail of the approximately 13-metre long skeleton. Based on stratigraphy, the age of the specimen was estimated at 67.83 million years, making it about one-and-a-half million years older than "Bèr". From what has been uncovered, this appears to be the oldest known Mosasaurid specimen from the Maastricht area, and it belongs to the genus Prognathodon.[15] The specimen is nicknamed Carlo, after the ENCI worker who discovered it.[16] [17]

Paleobiology

Paleoecology

The discovery of well-preserved specimens of Prognathodon overtoni in the Campanian Bearpaw Formation of Alberta, Canada allowed detailed studies of the gut contents (including fragments of a large and a small fish, a sea turtle and potentially a cephalopod) and dentition which allowed speculation into the ecology of Prognathodon. As with most mosasaurs, the teeth of these specimens are carinate, with the carinae aligned roughly parallel to the jaw. On unworn teeth, the apex is acute but blunt, and has fine, wavy, anastomosing ridges for as much as 25% of the crown height. Such ornamentation could potentially strengthen the teeth. The blunt tip and roughened surface suggest a tooth that was used for capturing fairly hard prey, and the presence of turtle bones as gut contents lends support to the hypothesis that Prognathodon was adapted to crush through hard-shelled prey.[2]

The teeth are, however, quite high relative to the size of the skull, which suggests that they were used for impaling prey rather than for crushing or grasping it. Many of the fully erupted teeth have crenulations on the carinae that produce a fine serration. The presence of serrated carinae would suggest that Prognathodon instead was an opportunistic predator comparable to modern killer whales, rather than particularly adapted to crush its prey. Such a predator can not only feed on very large vertebrate prey, but also feed upon a variety of other prey. However, P. overtoni teeth lack the pointed tip that is otherwise characteristic for opportunistic predators with "cutting" teeth. As such, the teeth of Prognathodon seemingly show adaptations not usually found together.[2]

It is worth noting that P. overtoni displays heterodonty similar to other mosasaurines, such as Globidens and Carinodens. For instance, the anterior teeth are more incurved and slender than those posterior to them with a gradual change in shape along the tooth row. The anterior teeth have a ratio of crown length to basal crown width of 2.0 to 2.5, whereas teeth in the middle of the tooth row have ratios in the range of 1.7 to 2.0. These ratios are consistent with both mosasaurs with "cutting" and "crushing" teeth. Though robust, the teeth of Prognathodon are nowhere near as broad as those of typical "crushing"-teeth mosasaurs, such as Globidens.[2]

The posteriormost teeth are sharply curved and short and were thus unlikely to have been used for prey capture or food processing. Teeth on the maxilla and dentary of both examined specimens show considerable wear. Crown apices are unusually smooth and polished, this breakage and subsequent polishing is likely due to prolonged contact with food. The tooth breakage is not severe and nearly horizontal, which is unlike typical predators with "cutting" teeth. The teeth may have been robust enough to prevent extensive breaking, or perhaps the curvature limited it. Many teeth are worn uniformly, which suggests a third possibility; that it represents a gradual grinding down of the teeth as a result of handling food. Somewhat similar wear is found on teeth of Globidens schurmanni, known to have fed on inoceramid bivalves.[2]

It is clear that the wear on the teeth does not represent simple breakage, since that would result in different amounts of wear on different teeth. In contrast to the marginal teeth, the pterygoid teeth, though unusually large for a mosasaur, do not exhibit any wear. This suggests that the marginal and pterygoid teeth had different functions, perhaps the pterygoid teeth were used to grip the prey before swallowing it. The large anterior pterygoid teeth that characterize Prognathodon likely provided an effective grip on large food items, indicating that the genus was capable of swallowing prey in large pieces.[2]

One of the Alberta specimens, TMP 2007.034.0001, is the first Prognathodon specimen with preserved gut contents. These contents include the remains of a very large (1.6 meter) fish, a smaller fish, a sea turtle and the possible remains of a cephalopod. These prey items are quite different from one another and would normally be prey items for different niches of predators, but are together consistent with a large and opportunistic apex predator. Though seemingly able to feed on prey typical for "cutting"-teeth mosasaurs, such as the large fish, the robust teeth suggest that somewhat harder prey, such as the sea turtle, was also commonly devoured.[2] Prognathodon overtoni, likely similar in ecology to other species of the genus, was thus likely an opportunistic predator capable of feeding upon nearly anything in the Western Interior Seaway.[2]

Taphonomy

The type specimen of Prognathodon saturator preserved several details that are taphonomically interesting. The likely cause of death of the specimen was age or disease, due to marine predators large enough to kill something of its size being unknown from the Maastrichtian. The degree of articulation of the specimen suggests that the animal reached the sea floor moments after its death, where it was scavenged by sharks prior to being buried by the sediments. Evidence of shark scavenging include the finds of associated teeth of shark genera Squalicorax and Plicatoscyllium among the bones of the mosasaur. It is possible to exclude the possibility of the sharks having been eaten by the mosasaurs prior to its death (and thus representing stomach contents) due to them showing no evidence of having been attacked by stomach acids. The number of shark teeth (not to mention the consistent size and color of the teeth) is also too high to be attributed to background abundance. The skeleton itself also preserves a variety of bite marks, providing direct evidence of shark scavenging.[9]

Pathology

A Prognathodon specimen known as NHMM 2012 (often nicknamed as "Carlo"), described by Bastiaans et al. in the journal Cretaceous Research in 2020, was discovered in the Netherlands near Maastricht, and was shown to have severe facial deformities including a devastating partial amputation of the premaxilla. The Prognathodon's injuries are believed to be the result of a fight with another mosasaur (likely another Prognathodon). This specimen shows signs of regrowth of bone around the injury as well as subsequent infections that were ongoing at the time of the mosasaur's death, which may have been partially caused by the injuries inflicted. The specimen stands as one of the few clearly confirmable cases of intra-specific combat between mosasaurs. It also revealed a very atypical immune response to the infection. Unlike modern reptilians where solid fibrous masses are produced to contain infections, this mosasaur showed a much more mammal-like response, including liquid pus. This is one of the first cases in which immunological responses in fossil taxa have been studied in such detail and where extant relatives differ to extinct taxa. [18]

Classification and species

Modern phylogenetic analyses continually place Prognathodon within the Mosasaurinae subfamily, despite this Prognathodon has historically been seen as a genus sharing close relations with Platecarpus and the Plioplatecarpinae. Louis Dollo was one of the earliest researchers to work on mosasaur systematics, initially placing them as a distinct lizard suborder and dividing the group into two families, the Mosasauridae and the "Plioplatecarpidae". In this early taxonomy, the Mosasauridae contained the genera Clidastes, Mosasaurus, Platecarpus, Halisaurus and Tylosaurus and the Plioplatecarpidae was monotypic, only containing Plioplatecarpus. In 1890, following further mosasaur discoveries (including that of Prognathodon), Dollo revised his taxonomy, dividing the Mosasauridae into three groups. These groups were based on how developed the rostrum was on the premaxilla, the size of the suprastapedial process of the quadrate and if the haemal arches were fused to the centra of the caudal vertebrae. Prognathodon was placed alongside Platecarpus in a "microrhynchous" group. The two other groups were the "megarhynchous" (including Tylosaurus and Hainosaurus) and the "mesorhynchous" (including Mosasaurus and Clidastes) groups.[6]

Dollo realized that Plioplatecarpus shared characters with the "microrhynchous" group in 1894 and abandoned his previous two family-system, starting to use only one family of mosasaurs, the Mosasauridae, and placing Prognathodon as closely related to Platecarpus and Plioplatecarpus.[6]

Russell (1967) retained Prognathodon within the Plioplatecarpinae, but erected a tribe for the genus and the related Plesiotylosaurus, the Prognathodontini. He considered the mosasaurs within the Prognathodontini to "clearly be of plioplatecarpine derivation", but justified the tribe by that they can be differentiated from other plioplatecarpines by their massive jaws and robust teeth.[6]

Gorden L. Bell Jr. conducted the first major phylogenetic analysis of mosasaurs in 1997, utilizing new methodologies and incorporating further taxa described since Russell's 1967 monograph (particularly basal mosasauroids, such as Aigialosaurus). Bell recovered Prognathodon within the Mosasaurinae, for the first time ever, as a close relative of the genera Globidens and Plesiotylosaurus. The tribe Prognathodontini was synonymized with the Globidensini, another tribe coined by Russell (1967) for Globidens. Bell was also the first to note that his analysis recovered Prognathodon, previously believed to be monophyletic, as paraphyletic.[19]

The view of the relationships of the genus to other mosasaur genera has changed little since 1997, it is routinely recovered as within the Mosasaurinae as well as paraphyletic. Cau and Madzia (2017) noted that the inclusion of Prognathodon and Plesiotylosaurus within the Globidensini would suggest a closer relationship between the genera than the reality of the situation. Though Prognathodon and Plesiotylosaurus are routinely recovered as sister genera, Cau and Madzia (2017) did not resurrect the tribe Prognathodontini in their list of mosasaur clades and their preferred definitions, offering no comment as to why not.[20] Within Cau and Madzia's analysis (as well as previous work such as Simões et al., 2017[21]), Prognathodon is recovered as a sister group to the Mosasaurini, and the clade Mosasaurini + Prognathodon itself was recovered as forming a sister group to the Globidensini.[20]

The results of a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the Mosasauridae by Simões et al. (2017)[21] is shown below, collapsed to only display the Mosasaurinae. The cladogram shows Prognathodon as paraphyletic, as concluded by most recent researchers, and places it as a sister group to the derived mosasaurines in the Mosasaurini.

| Mosasaurinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Species

A large number of species have been assigned to Prognathodon, though the genus is widely considered to be paraphyletic.[22] The incomplete nature of Prognathodon specimens has resulted in an incomplete understanding of the systematics of the genus as a whole, including both the alpha-level diversity and generic characteristics. Furthermore, the extreme rarity of early to middle Campanian specimens of Prognathodon has obscured the early part of its evolutionary history.[2]

The question of what constitutes Prognathodon is yet to be thoroughly examined. Lindgren (2005)[22] pointed out that robust and conical tooth crowns with blunt, serrated carinae and smooth enamel are routinely assigned to the genus, despite the generic type species, P. solvayi deviating from that description since it exhibits markedly labio-lingually compressed and gently facetted marginal teeth.

Species seen as valid and within Prognathodon, as recovered by Simões et al. (2017),[21] are listed below. Notably, the exclusion of the six controversial species significantly shortens both the temporal and geographical range of the genus, limiting it to Europe and the Middle East and removing any occurrence before the Late Campanian.

- Prognathodon solvayi Dollo, 1889 — Maastrichtian, Belgium and Spain.[23]

- P. solvayi is the type species of Prognathodon and also the smallest known species at barely 5 meters in length.[3] P. solvayi differs from all other members of the genus in several prominent aspects which is unusual for a type species. The most notable difference is perhaps in the teeth, which are gently facetted and labio-lingually compressed.[22]

- Prognathodon currii Christiansen and Bonde, 2002 — Late Campanian, Israel.

- P. currii is one of the largest, if not the largest, species of Prognathodon and is known from a single massive skull. The skull bears resemblance to Prognathodon, in particular to the type species P. solvayi, but differs from all known mosasaurs in having a frontal distinctly wider than it is long. Though originally informally named as part of its own genus, "Oronosaurus", multiple phylogenetic analyses found it to be firmly placed within Prognathodon.[24]

- Prognathodon giganteus Dollo, 1904 — Maastrichtian, Belgium, Jordan and Syria.[25]

- Prognathodon lutugini Yakovlev, 1901 — Late Campanian, Ukraine.

- Though not the largest, Prognathodon lutugini was a large species of Prognathodon at an estimated 8 meters in length.[22] It is sometimes classified as its own genus, "Dollosaurus" and has been recovered from deposits of Late Campanian age in Ukraine. Fossils described as "Dollosaurus sp." have been recovered from deposits of a similar age in Sweden and Russia,[26] and may thus belong to P. lutugini as well.

- Prognathodon lutugini differs from all other species of Prognathodon in its splenial-angular surface having distinct horizontal tongues and grooves, the shape of the vertebral condyle (being slightly depressed with a height to width ratio of 0.75) and the length proportions of the vertebrae (cervical vertebrae being almost equal in size to the longest vertebrae of the column). P. lutugini also differs from all other species except for P. solvayi by having 13 teeth in its dentary, though can be excluded from being sunked into P. solvayi due to its smooth enamel surface.[10]

- The absence of a dentary anterior projection differentiates P. lutugini from P. kianda, as well as P. lutugini having larger anterior pterygoid teeth. The lack of a medial striation on its tooth surfaces differentiates it from P. waiparaensis and P. solvayi. Additionally, the presence of carinae serrations on the teeth separates it from P. kianda and P. currii. The shape of the vertebral condyle (not being higher than they are wide) separates it from P. saturator and P. rapax.

- P. lutugini was originally named as a species of Clidastes by Yakovlev in 1901 based on the type specimen CNIGR 818, an incomplete skull and skeleton. Considering the combination of functionary accessory articulations and large pterygoid teeth to be unique, Yakovlev erected a new genus in 1905, Dollosaurus, named in honor of the belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo.[22] Lingham-Soliar (1989) showed that these characteristics were not unique to "Dollosaurus", which he synonymized on the genus level with Prognathodon.[7]

- Lindgren (2005)[22] noted that the taxonomic situation of P. lutugini (or "Dollosaurus") was somewhat unclear and that dental and osteological features suggested a placement within Prognathodon whilst the laterally pitted caudal vertebrae suggested a more distant relation. Furthermore, the controversy surrounding whether the genus Prognathodon is paraphyletic or not complicated a better look at the classification of the material referred to P. lutugini.

- A phylogenetic analysis conducted as part of the redescription of P. lutugini by D.V. Grigoriev (2013)[10] supported the referral of P. lutugini to Prognathodon and additionally suggested on a close relation with the type species P. solvayi.

Disputed and former species

The species Prognathodon kianda, P. overtoni, P. rapax, P. saturator, P. stadtmani and P. waiparaensis are recognised as being distinct mosasaur species, but their designation as species of Prognathodon is controversial and the latest phylogenetic analyses, such as Madzia and Cau (2017)[20] and Simões et al. (2017),[21] recover said species as outside the genus Prognathodon, most of them thus potentially representing genera on their own.

- Prognathodon kianda Schulp et al., 2008 — Maastrichtian, Angola.

- P. kianda is known from the Maastrichtian of Angola and is unique in possessing a high marginal tooth count and relatively small pterygoid teeth.[27] This species seemingly share close relations with the dubious genus Liodon and is regularly found to be outside of Prognathodon (and recovered as a far more basal mosasaurine) in most phylogenetic analyses.[10]

- Prognathodon overtoni Williston, 1897 — Campanian, Canada (Alberta) and the United States (Colorado and South Dakota).[28]

- P. overtoni can be distinguished from other species, including P. solvayi, by the smooth enamel of its teeth and their non-procumbant nature.[6] Previously classified as its own genus Brachysaurana before being lumped into Prognathodon, this is among the most completely known species of the genus, with several nearly complete and articulated specimens known, some of which even preserve gut contents.[2]

- Prognathodon rapax Hay, 1902 — Maastrichtian, the United States (Maryland and New Jersey).

- P. rapax is easily separated from species P. overtoni and P. solvayi by characters in the quadrate and has vertebral features closely resembling the vertebrae of Mosasaurus.[6]

- Prognathodon saturator Dortangs et al., 2002 — Maastrichtian, the Netherlands.

- P. saturator is a massively built and enormous species from the Maastrichtian of the Netherlands. P. saturator reached lengths of approximately 9-10 meters, perhaps only being shorter than P. overtoni (whose classification as Prognathodon is also controversial) and P. currii. The specific name saturator is Latin for "he who gives satisfaction", referring to that the type specimen was the first reasonably complete mosasaur specimen recovered from the Maastricht area since 1957.[9]

- The most obvious distinguishing feature of P. saturator that separates it from other species of Prognathodon is its massive size, larger than any other species of Prognathodon known at the time of its description, and being considerably more massive and robust in general. P. saturator also lacks the high crest on the dorsal median ridge which is found in other members of the genus. It can easily be distinguished from most other species by further, individual, differences. The Early Campanian P. stadtmani has a much more slender dentary, which also applies to P. waiparaensis. P. giganteus can be distinguished from P. saturator by its straight dorsal dental margin, its small coronoid, rectangular posterior mandibular unit and blunt retroarticular process as well as having a far less massive quadrate bone.[9]

- The type specimen, NHMM 1998141, preserves a near-complete skull, articulated cervical and anterior dorsal vertebrae with cervical and dorsal ribs, isolated pygal and caudal vertebrae, scapula-coracoid and scattered elements of the appendicular skeleton.[9]

- The robustness of the quadrate bone, along with the equally robust mandible, suggests that P. saturator could achieve bite forces in excess of all other mosasaurs. Compared to the quadrates of the genus Globidens and other species of Prognathodon, the one of P. saturator is even stronger built. With known examples of large sea turtles from the Maastricht region, such as Allopleuron, it is possible (based on found healed bite marks) that the size range of the prey of P. saturator included these 2.9 meter long turtles.[9]

- Prognathodon waiparaensis Welles and Gregg, 1971 — Maastrichtian, New Zealand.

- P. waiparaensis is known by a partial skeleton, including a disarticulated skull, cervical vertebrae, and ribs recovered from Maastrichtian-age deposits in New Zealand.[29]

Three species of the dubious genus Liodon (L. sectorius, L. compressidens and L. mosasauroides), two with a slender snout morphology, were assigned to Prognathodon in 2008 due to exhibiting similarity in the aspect ratios of their marginal dentition along the jaw margin to P. kianda.[27] In 2019 it was suggested by Mohr et al. that mosasauroides may perhaps be referable to the Maastrichtian-age genus Eremiasaurus based on unpublished morphological comparisons.[30] Palci et. al. (2014) however suggested the possibility that these three species, and perhaps also the type species of Liodon (L. anceps) were closer to Mosasaurus than to Prognathodon and that Liodon should perhaps instead by synonymized with Mosasaurus (though no formal proposal was made).[31]

The species P. stadtmani was redescribed as the type species of its own genus, Gnathomortis, in 2020.[32]

References

- ^ "Fossilworks: Prognathodon". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Konishi, Takuya; Brinkman, Donald; Massare, Judy A.; Caldwell, Michael W. (2011-09-01). "New exceptional specimens of Prognathodon overtoni (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the upper Campanian of Alberta, Canada, and the systematics and ecology of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (5): 1026–1046. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.601714. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 129001212.

- ^ a b Kaddumi, Hani F. "A new species of Prognathodon (Squamata: Mosasauridae) from the Maastrichtian of Harrana-Jordan".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Schulp, A. S., Vonhof, H. B., van der Lubbe, J. H. J. L., Janssen, R., & van Baal, R. R. (2013). On diving and diet: resource partitioning in type-Maastrichtian mosasaurs. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences - Geologie En Mijnbouw, 92(2-3), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/s001677460000010x

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2022). The Princeton Field Guide to Mesozoic Sea Reptiles. Princeton University Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780691193809.

- ^ a b c d e f g Russell, Dale. A. (6 November 1967). "Systematics and Morphology of American Mosasaurs" (PDF). Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History (Yale University).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k T, Lingham-Soliar; D., Nolf (1989). "The Mosasaur Prognathodon (Reptilia, Mosasauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Belgium". Bulletin van Het Koninklijk Belgisch Instituut voor Natuurwetenschappen. Aardwetenschappen = Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique. Sciences de la Terre.

- ^ Schulp, Anne S.; Jagt, John W. M.; Fonken, Frans (2004-09-10). "New material of the mosasaur Carinodens belgicus from the Upper Cretaceous of the Netherlands". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (3): 744–747. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0744:NMOTMC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 131741406.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "A large mosasaur from the Upper Cretaceous of The Netherlands (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2017-09-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grigoriev, D. V. (2013). "Redescription of Prognathodon lutugini (Squamata, Mosasauridae)" (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS. 317 (3): 246–261.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lindgren, Johan; Kaddumi, Hani F.; Polcyn, Michael J. (2013-09-10). "Soft tissue preservation in a fossil marine lizard with a bilobed tail fin". Nature Communications. 4: ncomms3423. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2423L. doi:10.1038/ncomms3423. PMID 24022259.

- ^ Lindgren, J.; Caldwell, M.W.; Konishi, T.; Chiappe, L.M. (2010). Farke, Andrew Allen (ed.). "Convergent Evolution in Aquatic Tetrapods: Insights from an Exceptional Fossil Mosasaur". PLOS ONE. 5 (8): e11998. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511998L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011998. PMC 2918493. PMID 20711249.

- ^ Christiansen, P.; Bonde, N. (2002). "A new species of gigantic mosasaur from the Late Cretaceous of Israel". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 629. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0629:ANSOGM]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 86139978.

- ^ Kaddumi, Hani F. (2009). "A new species of Prognathodon (Squamata: Mosasauridae) from the Maastrichtian of Harrana". Fossils of the Harrana Fauna and the Adjacent Areas. Amman: Eternal River Museum of Natural History. pp. 65–73. OCLC 709582892.

- ^ A Pathological Mosasaur snout from the Type Maastrichtian (SE Netherlands), Bastiaans et al, 2014, 2020.

- ^ "Pressrelease Natuurhistorisch Museum Maastricht". 20 September 2012. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ Bastiaans, Dylan; Kroll, Jeroen J.F.; Cornelissen, Dirk; Schulp, Anne S.; Jagt, John W.M. (February 2020). "Cranial palaeopathologies in a Late Cretaceous mosasaur from the Netherlands". Cretaceous Research. 112: 104425. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104425.

- ^ Bastiaans, Dylan; Kroll, Jeroen J.F.; Cornelissen, Dirk; Schulp, Anne S.; Jagt, John W.M. (February 2020). "Cranial palaeopathologies in a Late Cretaceous mosasaur from the Netherlands". Cretaceous Research. 112: 104425. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104425.

- ^ Bell GL. Jr. 1997. A phylogenetic revision of North American and Adriatic Mosasauroidea. pp. 293-332 In: Callaway JM, Nicholls EL, (eds.), Ancient Marine Reptiles, Academic Press, 501 pp.

- ^ a b c Madzia, D.; Cau, A. (2017). "Inferring "weak spots" in phylogenetic trees: application to mosasauroid nomenclature" (PDF). PeerJ. 5: e3782. doi:10.7717/peerj.3782. PMC 5602675. PMID 28929018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Simões, Tiago R.; Vernygora, Oksana; Paparella, Ilaria; Jimenez-Huidobro, Paulina; Caldwell, Michael W. (2017-05-03). "Mosasauroid phylogeny under multiple phylogenetic methods provides new insights on the evolution of aquatic adaptations in the group". PLOS ONE. 12 (5): e0176773. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1276773S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0176773. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5415187. PMID 28467456.

- ^ a b c d e f Lindgren, Johan (2005). "Dental and vertebral morphology of the enigmatic mosasaur Dollosaurus (Reptilia, Mosasauridae) from the lower Campanian (Upper Cretaceous) of southern Sweden". Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark. 52 (1): 17–25. ISSN 0011-6297.

- ^ "Fossilworks: Prognathodon solvayi". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Christiansen, Per; Bonde, Niels (2002). "A New Species of Gigantic Mosasaur from the Late Cretaceous of Israel". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (3): 629–644. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0629:ansogm]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4524254. S2CID 86139978.

- ^ "Fossilworks: Prognathodon giganteus". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Averianov, A. O.; Yarkov, A. A. (2004). "On the occurrence of a giant flying reptile (Pterosauria) in the terminal Late Cretaceous of the Lower Volga Region". Paleontological Journal. 38 (6): 669–671.

- ^ a b Schulp, Anne S.; Polcyn, Michael J.; Mateus, Octávio; Jacobs, Louis L.; Morais, Maria Luísa (2008). "A new species of Prognathodon (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Maastrichtian of Angola, and the affinities of the mosasaur genus Liodon". Proceedings of the Second Mosasaur Meeting.

- ^ "Fossilworks: Prognathodon overtoni". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Fossilworks: Prognathodon waiparaensis". fossilworks.org. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Mohr, LeBlanc, Caldwell, 2019. Redescription and Reassignment of “Liodon” mosasauroides to the Genus Eremiasaurus (Squamata, Mosasuaridae). SVP 2019, Annual Meeting, Program and Abstracts, 79A: 155.

- ^ Palci, Alessandro; Caldwell, Michael W.; Papazzoni, Cesare A.; Fornaciari, Eliana (2014). "Mosasaurine Mosasaurs (Squamara, Mosasauridae) from Northern Italy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (3): 549–559. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.826235. ISSN 0272-4634. JSTOR 24523277. S2CID 85773591.

- ^ Lively, J.R. (2020). "Redescription and phylogenetic assessment of 'Prognathodon' stadtmani: implications for Globidensini monophyly and character homology in Mosasaurinae". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (3): e1784183. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1784183.