Pulmonary circulation

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

| Pulmonary circulation | |

|---|---|

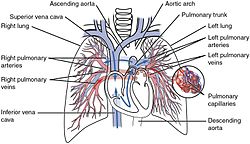

Human pulmonary circulation. Oxygen-rich blood is shown in red; oxygen-depleted blood in blue | |

Pulmonary circulation in the heart | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D011652 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The pulmonary circulation is the portion of the circulatory system which carries deoxygenated blood away from the right ventricle of the heart, to the lungs, and returns oxygenated blood to the left atrium and ventricle of the heart.[1] The term pulmonary circulation is readily paired and contrasted with the systemic circulation. The vessels of the pulmonary circulation are the pulmonary arteries and the pulmonary veins.

A separate system known as the bronchial circulation supplies oxygenated blood to the tissue of the larger airways of the lung.

Route

Deoxygenated blood leaves the heart, goes to the lungs, and then re-enters the heart; Deoxygenated blood leaves through the right ventricle through the pulmonary artery. From the right atrium, the blood is pumped through the tricuspid valve (or right atrioventricular valve), into the right ventricle. Blood is then pumped from the right ventricle through the pulmonary valve and into the main pulmonary artery.

Arteries

From the right ventricle, blood is pumped through the semilunar pulmonary valve into the left and right main pulmonary arteries (one for each lung), which branch into smaller pulmonary arteries that spread throughout the lungs.

Lungs

The pulmonary arteries carry deoxygenated blood to the lungs, where carbon dioxide is released and oxygen is picked up during respiration. Arteries are further divided into very fine capillaries which are extremely thin-walled. The pulmonary vein returns oxygenated blood to the left atrium of the heart.

Veins

The oxygenated blood then leaves the lungs through pulmonary veins, which return it to the left heart, completing the pulmonary cycle. This blood then enters the left atrium, which pumps it through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. From the left ventricle, the blood passes through the aortic valve to the aorta. The blood is then distributed to the body through the systemic circulation before returning again to the pulmonary circulation.

Arteries

From the right ventricle, blood is pumped through the semilunar pulmonary valve into the left and right main pulmonary arteries (one for each lung), which branch into smaller pulmonary arteries that spread throughout the lungs.

History

Pulmonary circulation was first described by the Arab physician Ibn al-Nafis in his Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon (1242). Ibn al-Nafis described pulmonary circulation as:[2][3]

"the blood from the right chamber of the heart must arrive at the left chamber but there is no direct pathway between them. The thick septum of the heart is not perforated and does not have visible pores as some people thought or invisible pores as Galen thought. The blood from the right chamber must flow through the vena arteriosa (pulmonary artery) to the lungs, spread through its substances, be mingled there with air, pass through the arteria venosa (pulmonary vein) to reach the left chamber of the heart and there form the vital spirit..."

It was later described by Michael Servetus in the "Manuscript of Paris"[4] (near 1546, never published) and later published in his Christianismi Restitutio (1553). Since it was a theology work condemned by most of the Christian factions of his time, the discovery remained mostly unknown until the dissections of William Harvey in 1616.

In 1559, Realdo Colombo explained the Pulmonary function. Prior to Colombo’s work, anatomists such as Galen and Vesalius examined blood vessels separately from the organs of the body. Colombo instead considered these vessels together with the organs they support, and from this was able to conceptualize the flow of blood to and from each organ, supporting his discovery of pulmonary transition of the blood. Colombo also viewed the lungs separately from the heart, and assigned it as having a special role in respiration.[5]

Embryonic

The pulmonary circulation loop is virtually bypassed in fetal circulation. The fetal lungs are collapsed, and blood passes from the right atrium directly into the left atrium through the foramen ovale: an open conduit between the paired atria, or through the ductus arteriosus: a shunt between the pulmonary artery and the aorta. When the lungs expand at birth, the pulmonary pressure drops and blood is drawn from the right atrium into the right ventricle and through the pulmonary circuit. Over the course of several months, the foramen ovale closes, leaving a shallow depression known as the fossa ovalis.

See also

External links

- Official Journal of the Pulmonary Vascular Research Institute

- Michael Servetus Research Study on the Manuscript of Paris with the description of the Pulmonary Circulation, and more works by Servetus.

References

- ^ Hine, Robert (2008). A dictionary of biology (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 540. ISBN 978-0-19-920462-5.

- ^ The Pursuit of Learning in the Islamic World, 610-2003 By Hunt Janin, Pg99

- ^ Saints and saviours of Islam, By Hamid Naseem Rafiabadi, Pg295

- ^ 2011 “The love for truth. Life and work of Michael Servetus”, (El amor a la verdad. Vida y obra de Miguel Servet.), printed by Navarro y Navarro, Zaragoza, collaboration with the Government of Navarra, Department of Institutional Relations and Education of the Government of Navarra, 607 pp, 64 of them illustrations, p 215-228 & 62nd illustration (XLVII)

- ^ Cunningham, Andrew (1997). The Anatomical Renaissance: The Resurrection of the Anatomical Projects of the Ancients. Scholar Press. p. 143. ISBN 1-85928-338-1.