Rapid eye movement sleep

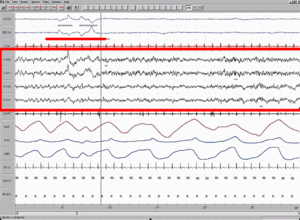

Rapid eye movement sleep (REM sleep) is a normal stage of sleep characterized by the rapid and random movement of the eyes. REM sleep is classified into two categories: tonic and phasic.[1] It was identified and defined by Nathaniel Kleitman, Eugene Aserinsky, and Jon Birtwell in the early 1950s. Criteria for REM sleep includes rapid eye movement, but also low muscle tone and a rapid, low-voltage EEG; these features are easily discernible in a polysomnogram,[2] the sleep study typically done for patients with suspected sleep disorders.[3]

REM sleep in adult humans typically occupies 20–25% of total sleep, about 90–120 minutes of a night's sleep. REM sleep normally occurs close to morning.[4] During a normal night of sleep, humans usually experience about four or five periods of REM sleep; they are quite short at the beginning of the night and longer toward the end. Many animals and some people tend to wake, or experience a period of very light sleep, for a short time immediately after a bout of REM. The relative amount of REM sleep varies considerably with age. A newborn baby spends more than 80% of total sleep time in REM.[5] During REM, the activity of the brain's neurons is quite similar to that during waking hours; for this reason, the REM-sleep stage may be called paradoxical sleep.[6]

REM sleep is physiologically different from the other phases of sleep, which are collectively referred to as non-REM sleep (NREM sleep). Subjects' vividly recalled dreams mostly occur during REM sleep.

Physiology

Physiologically, certain neurons in the brain stem, known as REM sleep-on cells, (located in the pontine tegmentum), are particularly active during REM sleep, and are probably responsible for its occurrence. The release of certain neurotransmitters, the monoamines (norepinephrine, serotonin and histamine), is completely shut down during REM.[7][8][9] This causes[citation needed] REM atonia, a state in which the motor neurons are not stimulated and thus the body's muscles do not move. Lack of such REM atonia causes REM behavior disorder; sufferers act out the movements occurring in their dreams. Heart rate and breathing rate are irregular during REM sleep, again similar to the waking hours. Body temperature is not well regulated during REM. Erections of the penis (nocturnal penile tumescence or NPT) normally accompany REM sleep. If a male has erectile dysfunction (ED) while awake, but has NPT episodes during REM, it would suggest that the ED is from a psychological rather than a physiological cause. In females, erection of the clitoris (nocturnal clitoral tumescence or NCT) causes enlargement, with accompanying vaginal blood flow and transudation (i.e. lubrication). During a normal night of sleep the penis and clitoris may be erect for a total time of from one hour to as long as three and a half hours during REM.

Theories about the function(s) of REM sleep

The function of REM sleep is not well understood; several theories have been proposed.

According to one theory, certain memories are consolidated during REM sleep. Numerous studies have suggested that REM sleep is important for consolidation of procedural memory and spatial memory. (Slow-wave sleep, part of non-REM sleep, appears to be important for declarative memory.) A recent study[10] shows that artificial enhancement of the non-REM sleep improves the next-day recall of memorized pairs of words. Tucker et al. demonstrated that a daytime nap containing solely non-REM sleep enhances declarative memory but not procedural memory.[11] The role of REM sleep in memory, however, is not without its doubts. Monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants can suppress REM sleep, yet these drugs show no evidence of impairing memory. On the contrary, some studies show MAO inhibitors improve memory. Moreover, one case study of an individual who had little or no REM sleep due to a shrapnel injury to the brainstem did not find the individual's memory to be impaired. (For a more detailed critique on the link between sleep and memory, see Ref.[12])

Intimately related to views on REM function in memory consolidation, Mitchison and Crick[13] have proposed that by virtue of its inherent spontaneous activity, the function of REM sleep "is to remove certain undesirable modes of interaction in networks of cells in the cerebral cortex", which process they characterize as "unlearning". As a result, those memories which are relevant (whose underlying neuronal substrate is strong enough to withstand such spontaneous, chaotic activation), are further strengthened, whilst weaker, transient, "noise" memory traces disintegrate.

Stimulation in CNS development as a primary function

According to another theory, known as the Ontogenetic Hypothesis of REM sleep, this sleep stage (also known as active sleep in neonates) is particularly important to the developing brain, possibly because it provides the neural stimulation that newborns need to form mature neural connections and for proper nervous system development.[14] Studies investigating the effects of active sleep deprivation have shown that deprivation early in life can result in behavioral problems, permanent sleep disruption, decreased brain mass,[15] and result in an abnormal amount of neuronal cell death.[16] Further supporting this theory is the fact that the amount of REM sleep in humans decreases with age, as well as data from other species (see below).

One important theoretical consequence of the Ontogenetic Hypothesis is that REM sleep may have no essentially vital function in the mature brain, i.e., once the development of CNS has completed. However, because processes of neuronal plasticity do not cease altogether in the brain,[17] REM sleep may continue to be implicated in neurogenesis in adults as a source of sustained spontaneous stimulation.

Other theories

Yet another theory suggests that monoamine shutdown is required so that the monoamine receptors in the brain can recover to regain full sensitivity. Indeed, if REM sleep is repeatedly interrupted, the person will compensate for it with longer REM sleep, "rebound sleep", at the next opportunity.

It has been suggested that acute REM sleep deprivation can improve certain types of depression when depression appears to be related to an imbalance of certain neurotransmitters. Although sleep deprivation in general annoys most of the population, it has repeatedly been shown to alleviate depression, albeit temporarily.[18] More than half the individuals who experience this relief report it to be rendered ineffective after sleeping the following night. Thus, researchers have devised methods such as altering the sleep schedule for a span of days following a REM deprivation period[19] and combining sleep-schedule alterations with pharmacotherapy[20] to prolong this effect. Though most antidepressants selectively inhibit REM sleep due to their action on monoamines, this effect decreases after long-term use. It is interesting to note that REM sleep deprivation stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis much the same as antidepressants.[21]

Some researchers argue that the perpetuation of a complex brain process such as REM sleep indicates that it serves an important function for the survival of mammalian and avian species. It fulfills important physiological needs vital for survival to the extent that prolonged REM sleep deprivation leads to death in experimental animals.[citation needed] In both humans and experimental animals, REM sleep loss leads to several behavioral and physiological abnormalities.[citation needed] Loss of REM sleep has been noticed during various natural and experimental infections. Survivability of the experimental animals decreases when REM sleep is totally attenuated during infection; this leads to the possibility that the quality and quantity of REM sleep is generally essential for normal body physiology.

The sentinel hypothesis of REM sleep was put forward by Frederick Snyder in 1966. It is based upon the observation that REM sleep in several mammals (the rat, the hedgehog, the rabbit, and the rhesus monkey) is followed by a brief awakening. This does not occur for either cats or humans, although humans are more likely to wake from REM sleep than from NREM sleep. Snyder hypothesized that REM sleep activates an animal periodically, to scan the environment for possible predators. This hypothesis does not explain the muscle paralysis of REM sleep; however, a logical analysis might suggest that the muscle paralysis exists to prevent the animal from fully waking up unnecessarily, and allowing it to return easily to deeper sleep.[22][23][24]

Effect of sleep deprivation on REM sleep

Studies have shown that people sleep more efficiently when they are sleep-deprived and that they enter REM sleep faster when this is the case. Sleep studies also show that patients who sleep less move to stage 3 and REM sleep faster than patients who are not sleep deprived.[25]

REM sleep and creativity

Sleep aids the process by which creativity forms associative elements into new combinations that are useful or meet some requirement.[26] This occurs in REM sleep rather than in NREM sleep.[27][28] Rather than being due to memory processes, this has been attributed to changes during REM sleep in cholinergic and noradrenergic neuromodulation.[27] During REM sleep high levels of acetylcholine in the hippocampus suppress feedback from hippocampus to the neocortex, and lower levels of acetylcholine and norepinephrine in the neocortex encourage the spread of associational activity within neocortical areas without control from the hippocampus.[29] This is in contrast to waking consciousness, where higher levels of norepinephrine and acetylcholine inhibit recurrent connections in the neocortex. REM sleep through this process adds creativity by allowing "neocortical structures to reorganise associative hierarchies, in which information from the hippocampus would be reinterpreted in relation to previous semantic representations or nodes."[27]

REM sleep in animals

REM sleep occurs in all land mammals.

Theories about the function of rapid eye movements

According to "scanning hypothesis" the directional properties of REM sleep eye movements are related to shifts of gaze in dream imagery. Against this hypothesis is that such eye movements occur in those born blind and in fetuses in spite of lack of vision. Also binocular REMs are non-conjugated and so lack a fixation point. In support, research finds that in goal-oriented dreams, eye gaze is directed towards the action described by the dreamer.[30]

Other theories are that they lubricate the cornea, warm the brain, stimulate and stabilize the neural circuits that have not been activated during waking, create internal stimulation to aid development of the CNS, or lack any purpose, being random creation of brain activation.[30]

Discovery

The phenomenon of REM sleep and its association with dreaming was discovered by Eugene Aserinsky and Nathaniel Kleitman with assistance from William C. Dement, a medical student at the time, in 1952 during their tenures at the University of Chicago. Kleitman and Aserinsky's seminal article was published September 10, 1953.[31]

See also

- Sleep and learning

- Dream

- Non-rapid eye movement sleep

- Lucid dream

- Pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN)

- PGO waves

- REM rebound

References

- ^ Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W (2000). Principles & Practices of Sleep Medicine. WB Saunders Company. pp. 1, 572.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "[Polysomnography]". Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Koval'zon, VM (2011 Jul-Aug). "[Central mechanisms of sleep-wakefulness cycle]". Fiziologiia cheloveka. 37 (4): 124–34. PMID 21950094.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ http://kidshealth.org/kid/feeling/emotion/nightmares.html

- ^ [1]

- ^ Myers, David (2004). Psychology (7th ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. p. 268. ISBN 0-7167-8595-1. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ^ Hobson, J.A. (2009). "REM sleep and dreaming: towards a theory of protoconsciousness". Nature Reviews. 10 (11): 803–813. doi:10.1038/nrn2716. PMID 19794431.

- ^ Aston-Jones G., Gonzalez M., & Doran S. (2007). "Role of the locus coeruleus-norepinephrine system in arousal and circadian regulation of the sleep-wake cycle." Ch. 6 in Brain Norepinephrine: Neurobiology and Therapeutics. G.A. Ordway, M.A. Schwartz, & A. Frazer, eds. Cambridge UP. 157–195. Accessed 21 Jul. 2010. Academicdepartments.musc.edu

- ^ Siegel J.M. (2005). "REM Sleep." Ch. 10 in Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 4th ed. M.H. Kryger, T. Roth, & W.C. Dement, eds. Elsevier. 120–135. Accessed 21 July 2010. Psychology.uiowa.edu

- ^ Marshall, Helgadóttir, Mölle & Born, 2006

- ^ Tucker, Matthew A.; Hirota, Yasutaka; Wamsley, Erin J.; Lau, Hiuyan; Chaklader, Annie; Fishbein, William (2006). "A daytime nap containing solely non-REM sleep enhances declarative but not procedural memory" (PDF). Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 86 (2). Elsevier. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|pages241-247=(help) - ^ Siegel, Jerome M. "The REM Sleep-Memory Consolidation Hypothesis".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Mitchison, Graeme; Crick, Francis (1983). "The function of dream sleep". Nature. 304 (5922): 111–14. doi:10.1038/304111a0. PMID 6866101.

- ^ Marks et al. 1994

- ^ Mirmiran et al. 1983

- ^ Morrissey, Duntley & Anch, 2004

- ^ Bruel-Jungerman E, Rampon C, Laroche S (2006). "Adult hippocampal neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity and memory: facts and hypotheses". Rev. Neurosci. 18 (2): 93–114. PMID 17593874.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ringel, B. L., & Szuba, M. P. (2001). "Potential mechanisms of the sleep therapies for depression". Depression and Anxiety, 14(1), 29-36. doi:10.1002/da.1044.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Riemann, D. D., König, A. A., Hohagen, F. F., Kiemen, A. A., Voderholzer, U. U., Backhaus, J. J., & ... Berger, M. M. (1999). "How to preserve the antidepressive effect of sleep deprivation: A comparison of sleep phase advance and sleep phase delay". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 249(5), 231-237. doi:10.1007/s004060050092.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Wirz-Justice, A., & Van den Hoofdakker, R. H. (1999). "Sleep deprivation in depression: What do we know, where do we go?". Biological Psychiatry, 46(4), 445-453.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Zucconi, G., Cipriani, S., Balgkouranidou, I., & Scattoni, R. (2006). "'One night' sleep deprivation stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis. \publisher=Brain Research Bulletin, 69(4), 375-381. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.01.009".

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Steven J. Ellman and John S. Antrobus (1991). "Effects of REM deprivation". The Mind in Sleep: Psychology and Psychophysiology. John Wiley and Sons. p. 398. ISBN 0-471-52556-1.

- ^ Michel Jouvet (2001). The Paradox of Sleep: The Story of Dreaming. Translated by Laurence Garey. MIT Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-262-60040-4.

- ^ William H. Moorcroft and Paula Belcher (2003). "Functions of REMS and Dreaming". Understanding Sleep and Dreaming. Springer. p. 290. ISBN 0-306-47425-5.

- ^ "About.com Published Study".

- ^ Wagner, U; Gais, S; Haider, H; Verleger, R; Born, J. (2004). "Sleep inspires insight". Nature. 427 (6972): 352–5. doi:10.1038/nature02223. PMID 14737168.

- ^ a b c Cai, DJ; Mednick, SA; Harrison, EM; Kanady, JC; Mednick, SC (2009). "REM, not incubation, improves creativity by priming associative networks". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 106 (25): 10130–10134. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900271106. PMC 2700890. PMID 19506253.

- ^ Walker, MP; Liston, C; Hobson, JA; Stickgold, R (November 2002). "Cognitive flexibility across the sleep-wake cycle: REM-sleep enhancement of anagram problem solving". Brain research. Cognitive brain research. 14 (3): 317–24. doi:10.1016/S0926-6410(02)00134-9. PMID 12421655.

- ^ Hasselmo, ME (September 1999). "Neuromodulation: acetylcholine and memory consolidation". Trends in cognitive sciences. 3 (9): 351–359. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(99)01365-0. PMID 10461198.

- ^ a b Leclair-Visonneau L, Oudiette D, Gaymard B, Leu-Semenescu S, Arnulf I. (2010). Do the eyes scan dream images during rapid eye movement sleep? Evidence from the rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder model. Brain. doi:10.1093/brain/awq110 133(Pt 6):1737–46. PMID 20478849

- ^ Aserinsky E. and Kleitman N. (1953). "Regularly Occurring Periods of Eye Motility, and Concomitant Phenomena, during Sleep". Science. 118 (3062): 273–274. doi:10.1126/science.118.3062.273. PMID 13089671.

[Add reference: Carson III, Culley C., Kirby, Roger S., Goldstein, Irwin, editors, "Textbook of Erectile Dysfunction" Oxford, U.K.; Isis Medical Media, Ltd., 1999; Moreland, R.B. & Nehra, A.; Pathosphysiology of erectile dysfunction; a molecular basis, role of NPT in maintaining potency: pp. 105–15.]

Further reading

- Frederick Snyder (1966). "Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Dreaming". American Journal of Psychiatry. 123 (2): 121–142. PMID 5329927.

- Edward F. Pace-Schott, ed. (2003). Sleep and Dreaming: Scientific Advances and Reconsiderations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00869-7.

- Koulack, D. To Catch A Dream: Explorations of Dreaming. New York, SUNY, 1991.

External links

- LSDBase - an open sleep research database with images of REM sleep recordings.

- The REM sleep in the expectation fulfillment theory of dreaming