Sioux language

A major contributor to this article appears to have a close connection with its subject. (December 2021) |

| Sioux | |

|---|---|

| Dakota, Lakota | |

| Native to | United States, Canada |

| Region | Northern Nebraska, southern Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, northeastern Montana; southern Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan |

Native speakers | 25,000[1] (2015)[2] |

Siouan

| |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | dak |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:dak – Dakotalkt – Lakota |

| Glottolog | dako1258 Dakotalako1247 Lakota |

| ELP | Sioux |

| Linguasphere | Dakota 62-AAC-a Dakota |

Sioux is a Siouan language spoken by over 30,000 Sioux in the United States and Canada, making it the fifth most spoken indigenous language in the United States or Canada, behind Navajo, Cree, Inuit languages, and Ojibwe.[4][5]

Since 2019, "the language of the Great Sioux Nation, comprised of three dialects, Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota" is the official indigenous language of South Dakota.[6][3]

Regional variation

Sioux has three major regional varieties, with other sub-varieties:

- Lakota (a.k.a. Lakȟóta, Teton, Teton Sioux)

- Western Dakota (a.k.a. Yankton-Yanktonai or Dakȟóta, and erroneously classified, for a very long time, as "Nakota"[7])

- Yankton (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ)

- Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna)

- Eastern Dakota (a.k.a. Santee-Sisseton or Dakhóta)

- Santee (Isáŋyáthi: Bdewákhathuŋwaŋ, Waȟpékhute)

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ)

Yankton-Yanktonai (Western Dakota) stands between Santee-Sisseton (Eastern Dakota) and Lakota within the dialect continuum. It is phonetically closer to Santee-Sisseton but lexically and grammatically, it is much closer to Lakota. For this reason Lakota and Western Dakota are much more mutually intelligible than each is with Eastern Dakota. The assumed extent of mutual intelligibility is usually overestimated by speakers of the language. While Lakota and Yankton-Yanktonai speakers understand each other to a great extent, they each find it difficult to follow Santee-Sisseton speakers.

Closely related to the Sioux language are the Assiniboine and Stoney languages, whose speakers use the self-designation term (autonym) Nakhóta or Nakhóda.

Comparison of Sioux and Nakota languages and dialects

Phonetic differences

The following table shows some of the main phonetic differences between the regional varieties of the Sioux language. The table also provides comparison with the two closely related Nakota languages (Assiniboine and Stoney).[8]

| Sioux | Assiniboine | Stoney | gloss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lakota | Western Dakota | Eastern Dakota | |||||

| Yanktonai | Yankton | Sisseton | Santee | ||||

| Lakȟóta | Dakȟóta | Dakhóta | Nakhóta | Nakhóda | self-designation | ||

| lowáŋ | dowáŋ | dowáŋ | nowáŋ | to sing | |||

| ló | dó | dó | nó | assertion | |||

| čísčila | čísčina | čístina | čúsina | čúsin | small | ||

| hokšíla | hokšína | hokšína | hokšída | hokšína | hokšín | boy | |

| gnayáŋ | gnayáŋ | knayáŋ | hnayáŋ | knayáŋ | hna | to deceive | |

| glépa | gdépa | kdépa | hdépa | knépa | hnéba | to vomit | |

| kigná | kigná | kikná | kihná | kikná | gihná | to soothe | |

| slayá | sdayá | sdayá | snayá | snayá | to grease | ||

| wičháša | wičháša | wičhášta | wičhášta | wičhá | man | ||

| kibléza | kibdéza | kibdéza | kimnéza | gimnéza | to sober up | ||

| yatkáŋ | yatkáŋ | yatkáŋ | yatkáŋ | yatkáŋ | to drink | ||

| hé | hé | hé | žé | žé | that | ||

Lexical differences

| English gloss | Santee-Sisseton | Yankton-Yanktonai | Lakota | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Lakota | Southern Lakota | |||

| child | šičéča | wakȟáŋyeža | wakȟáŋyeža | |

| knee | hupáhu | čhaŋkpé | čhaŋkpé | |

| knife | isáŋ / mína | mína | míla | |

| kidneys | phakšíŋ | ažúŋtka | ažúŋtka | |

| hat | wapháha | wapȟóštaŋ | wapȟóštaŋ | |

| still | hináȟ | naháŋȟčiŋ | naháŋȟčiŋ | |

| man | wičhášta | wičháša | wičháša | |

| hungry | wótehda | dočhíŋ | ločhíŋ | |

| morning | haŋȟ’áŋna | híŋhaŋna | híŋhaŋna | híŋhaŋni |

| to shave | kasáŋ | kasáŋ | kasáŋ | glak’óǧa |

Writing systems

This article should specify the language of its non-English content, using {{lang}}, {{transliteration}} for transliterated languages, and {{IPA}} for phonetic transcriptions, with an appropriate ISO 639 code. Wikipedia's multilingual support templates may also be used. (September 2021) |

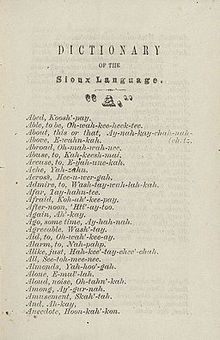

In 1827, John Marsh and his wife, Marguerite (who was half Sioux), wrote the first dictionary of the Sioux language. They also wrote a "Grammar of the Sioux Language."[9][10]

Life for the Dakota changed significantly in the nineteenth century as the early years brought increased contact with white settlers, particularly Christian missionaries. The goal of the missionaries was to introduce the Dakota to Christian beliefs. To achieve this, the missions began to transcribe the Dakota language. In 1836, brothers Samuel and Gideon Pond, Rev. Stephen Return Riggs, and Dr. Thomas Williamson set out to begin translating hymns and Bible stories into Dakota. By 1852, Riggs and Williamson had completed a Dakota Grammar and Dictionary (Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Center). Eventually, the entire Bible was translated.

Today, it is possible to find a variety of texts in Dakota. Traditional stories have been translated, children's books, even games such as Pictionary and Scrabble. Despite such progress, written Dakota is not without its difficulties. The Pond brothers, Rev. Riggs, and Dr. Williamson were not the only missionaries documenting the Dakota language. Around the same time, missionaries in other Dakota bands were developing their own versions of the written language. Since the 1900s, professional linguists have been creating their own versions of the orthography. The Dakota have also been making modifications. "Having so many different writing systems is causing confusion, conflict between our [the Dakota] people, causing inconstancy in what is being taught to students, and making the sharing of instructional and other materials very difficult" (SICC).

Prior to the introduction of the Latin alphabet, the Dakota did have a writing system of their own: one of representational pictographs. In pictographic writing, a drawing represents exactly what it means. For example, a drawing of a dog literally meant a dog. Palmer writes that,

As a written language, it [pictographs] was practical enough that it allowed the Lakota to keep a record of years in their winter counts which can still be understood today, and it was in such common usage that pictographs were recognized and accepted by census officials in the 1880s, who would receive boards or hides adorned with the head of the household’s name depicted graphically. (pg. 34)[full citation needed]

For the missionaries, however, documenting the Bible through pictographs was impractical and presented significant challenges.

| IPA | Buechel & Manhart spelling (pronunciation) |

Standard orthography[11] | Brandon University |

Deloria & Boas |

Dakota Mission |

Rood & Taylor |

Riggs[12] | Williamson | University of Minnesota |

White Hat | Txakini Practical[13] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʔ | ´ | ´ | ʾ | ´ | none | ʼ | ´ | ´ | ´ | none | ' |

| a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a |

| aː | a (á) | á | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | 'a[note 1] |

| ã | an, an' (aƞ) | aŋ | an̄ | ą | an | ą | aŋ | aŋ | aŋ | aƞ | an |

| p~b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b |

| tʃ | c | č | c | c | c | č | ć | c | c | c̄ | c |

| tʃʰ | c (c, c̔) | čh | ć | cʽ | c | čh | ć̣ | c̣ | c | ċ[note 2] | ch |

| tʃʼ | c’ | č’ | c̦ | c’ | c | čʼ | ć | c | c’ | ċ’[note 2] | c' |

| t~d | none | none | d | d | d | d | d | d | d | d | d |

| e~ɛ | e | e | e | e | e | e | e | e | e | e | e |

| eː~ɛː | e (é) | é | e | e | e | e | e | e | e | e | 'e[note 1] |

| k~ɡ | g | g | g | g | g | g | g | g | g | g | g |

| ʁ~ɣ | g (ġ) | ǧ | ǥ | ġ | g | ǧ | ġ | ġ | g | ġ | gx |

| h | h | h | h | h | h | h | h | h | h | h | h |

| χ | h̔ | ȟ | ħ | ḣ | r | ȟ | ḣ | ḣ | ḣ | ḣ | x |

| χʔ~χʼ | h’ (h̔’) | ȟ’ | ħ̦ | ḣ’ | r | ȟʼ | ḣ | ḣ | ḣ’ | ḣ’ | x' |

| i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i |

| iː | i (í) | í | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | i | 'i[note 1] |

| ĩ | in, in' (iƞ) | iŋ | in̄ | į | in | į | iŋ | iŋ | iŋ | iƞ | in |

| k | k (k, k̇) | k | k | k | k | k | k | k | k | k | k |

| kʰ~kˣ | k | kh | k̔ | k‘ | k | kh | k | k | ḳ | k | kh |

| qˣ~kˠ | k (k̔) | kȟ | k̔ | k‘ | k | kh | k | k | ḳ | k̇ | kx |

| kʼ | k’ | k’ | ķ | k’ | q | kʼ | ḳ | ḳ | k’ | k’ | k' |

| l | l | l | none | l | none | l | l | l | none | l | l |

| lː | l´ | none | none | none | none | none | none | none | none | none | none |

| m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m |

| n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| ŋ | n | n | n | n | n | ň | n | n | n | n | ng |

| o | o | o | o | o | o | o | o | o | o | o | o |

| oː | o (ó) | ó | o | o | o | o | o | o | o | o | 'o[note 1] |

| õ~ũ | on, on' (oƞ) | uŋ | un̄ | ų | on | ų | oŋ | oŋ | uŋ | uƞ | un |

| p | ṗ (p, ṗ) | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p | p̄ | p |

| pʰ | p | ph | p̔ | p‘ | p | ph | p | p | p̣ | p | ph |

| pˣ~pˠ | p (p̔) | pȟ | p̔ | p‘ | p | ph | p | p | p̣ | ṗ | px |

| pʼ | p’ | p’ | p̦ | p’ | p | pʼ | p̣ | p̣ | p’ | p’ | p' |

| s | s | s | s | s | s | s | s | s | s | s | s |

| sʼ | s’ | s’ | ș | s’ | s | sʼ | s’ | s’ | s’ | s’ | s' |

| ʃ | š | š | š | ṡ | x, ś | š | ś | ṡ | ṡ | ṡ[note 3] | sh |

| ʃʔ~ʃʼ | š’ | š’ | ș̌ | ṡ’ | x, ś | š | ś’ | ṡ’ | ṡ’ | ṡ’[note 3] | sh' |

| t | t (t, ṫ) | t | t | t | t | t | t | t | t | t | t |

| tʰ | t | th | tʿ | tʽ | t | th | t | t | ṭ | t | th |

| tˣ~tˠ | t (t̔) | tȟ | tʿ | tʽ | t | th | t | t | ṭ | ṫ | tx |

| tʼ | t’ | t’ | ţ | t’ | t | tʼ | ṭ | ṭ | t’ | t’ | t' |

| u | u | u | u | u | u | u | u | u | u | u | u |

| uː | u (ú) | ú | u | u | u | u | u | u | u | u | 'u[note 1] |

| õ~ũ | un, un' (uƞ) | uŋ | un̄ | ų | un | ų | uŋ | uŋ | uŋ | uƞ | un |

| w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w |

| j | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y | y |

| z | z | z | z | z | z | z | z | z | z | z | z |

| ʒ | j | ž | ž | z | j | ž | ź | ż | ż | j | zh |

Structure

Phonology

See Lakota language – Phonology and Dakota language – Phonology.

Morphology

Dakota is an agglutinating language. It features suffixes, prefixes, and infixes. Each affix has a specific rule in Dakota. For example, the suffix –pi is added to the verb to mark the plurality of an animate subject.[14] "With respect to number agreement for objects, only animate objects are marked, and these by the verbal prefix wicha-."[15] Also, there is no gender agreement in Dakota.

Example of the use of –pi:[16]

ma-khata

I-hot

"I am hot"

khata-pi

0-hot-PL

"they are hot"

Example of the use of wicha-

wa-kte

0-I-kill

"I kill him"

wicha-wa-kte

them-I-kill

"I kill them"

Infixes are rare in Dakota, but do exist when a statement features predicates requiring two "patients".

Example of infixing:

iye-checa

to resemble

→

iye-ni-ma-checa

I resemble you

"you resemble me"

iskola

be as small as

→

i-ni-ma-skola

I am as small as you

"you are as small as I"

Syntax

Dakota has subject/object/ verb (SOV) word order. Along the same line, the language also has postpositions. Examples of word order:[14]

wichasta-g

man-DET

wax aksica-g

bear-DET

kte

kill

"the man killed the bear"

wax aksicas-g

bear-DET

wichasta-g

man-DET

kte

kill

"the bear killed the man"

According to Shaw, word order exemplifies grammatical relations.

In Dakota, the verb is the most important part of the sentence. There are many verb forms in Dakota, although they are "dichotomized into a stative-active classification, with the active verbs being further subcategorized as transitive or intransitive."[15] Some examples of this are:[17]

- stative:

- ma-khata "I am hot" (I-hot)

- ni-khata "you are hot" (you-hot)

- khata "he/she/it is hot" (0-hot)

- u-khata "we (you and I) are hot" (we-hot)

- u-khata-pi "we (excl. or pl) are hot" (we-hot-pl.)

- ni-khata-pi "you (pl.) are hot" (you-hot-pl.)

- khata-pi "they are hot" (0-hot-pl.)

- active intransitive

- wa-hi "I arrive (coming)" (I-arrive)

- ya-hi "you arrive" (you-arrive)

- hi "he arrives"

- u-hi "we (you and I) arrive"

- u-hi-pi "we (excl. or pl.) arrive"

- ya-hi-pi "you (pl.) arrive"

- hi-pi they arrive"

- active transitive

- wa-kte "I kill him" (0-I-kill)

- wicha-wa-kte "I kill them" (them-I-kill)

- chi-kte "I kill you" (I-you (portmanteau)- kill)

- ya-kte "you kill him" (0-you-kill)

- wicha-ya-kte "you kill them" (them- you-kill)

- wicha-ya-kte-pi "you (pl.) kill them"

- ma-ya-kte "you kill me" (me-you-kill)

- u-ya-kte-pi "you kill us" (we-you-kill-pl.)

- ma-ktea "he kills me" (0-me-kill-pl.)

- ni-kte-pi "they kill you" (0-you-kill-pl.)

- u-ni-kte-pi "we kill you" (we-you-kill-pl.)

- wicha-u-kte "we (you and I) kill them" (them-we-kill)

The phonology, morphology, and syntax of Dakota are very complex. There are a number of broad rules that become more and more specific as they are more closely examined. The components of the language become somewhat confusing and more difficult to study as more sources are examined, as each scholar has a somewhat different opinion on the basic characteristics of the language.

Notes

- ^ UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger

- ^ Dakota at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Lakota at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) - ^ a b South Dakota Legislature (2019): Amendment for printed bill 126ca

- ^ Estes, James (1999). "Indigenous Languages Spoken in the United States (by Language)". yourdictionary.com. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ Statistics Canada: 2006 Census Archived 2013-10-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kaczke, Lisa (March 25, 2019). "South Dakota recognizes official indigenous language". Argus Leader. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ for a report on the long-established error of the Yankton and the Yanktonai as "Nakota", see the article Nakota

- ^ Parks, Douglas R.; DeMallie, Raymond J. (1992). "Sioux, Assiniboine, and Stoney Dialects: A Classification". Anthropological Linguistics. 34 (1–4): 233–255. JSTOR 30028376.

- ^ Winkley, John W. Dr. John Marsh: Wilderness Scout, pp. 22-3, 35, The Partnenon Press, Nashville, Tennessee, 1962.

- ^ Lyman, George D. John Marsh, Pioneer: The Life Story of a Trail-blazer on Six Frontiers, pp. 79-80, The Chautauqua Press, Chautauqua, New York, 1931.

- ^ Orthography of the New Lakota Dictionary

- ^ Riggs, p. 13

- ^ "Lakota orthographies". Society to Advance Indigenous Vernaculars of the United States. 2011. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

- ^ a b Shaw, P.A. (1980). Theoretical issues in Dakota phonology and morphology. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc. p. 10.

- ^ a b Shaw 1980, p. 11.

- ^ Shaw 1980, p. 12.

- ^ Shaw 1980, pp. 11–12.

Bibliography

- Bismarck Tribune. (2006, March 26). Scrabble helps keep Dakota language alive. Retrieved November 30, 2008, from [1]

- Catches, Violet (1999?). Txakini-iya Wowapi. Lakxota Kxoyag Language Preservation Project.

- DeMallie, Raymond J. (2001). "The Sioux until 1850". In R. J. DeMallie (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 2, pp. 718–760). W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- de Reuse, Willem J. (1987). One hundred years of Lakota linguistics (1887–1987). Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics, 12, 13–42. (Online version: https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/dspace/handle/1808/509).

- de Reuse, Willem J. (1990). A supplementary bibliography of Lakota languages and linguistics (1887–1990). Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics, 15 (2), 146–165. (Studies in Native American languages 6). (Online version: https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/dspace/handle/1808/441).

- Eastman, M. H. (1995). Dahcotah or, life and legends of the Sioux around Fort Snelling. Afton: Afton Historical Society Press.

- Howard, J. H. (1966). Anthropological papers number 2: the Dakota or Sioux Indians: a study in human ecology. Vermillion: Dakota Museum.

- Hunhoff, B. (2005, November 30). "It's safely recorded in a book at last". South Dakota Magazine: Editor's Notebook. Retrieved November 30, 2008, from [2]

- McCrady, D.G. (2006). Living with strangers: the nineteenth-century Sioux and the Canadian-American borderlands. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Palmer, J.D. (2008). The Dakota peoples: a history of the Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota through 1863. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

- Parks, D.R. & DeMallie, R.J. (1992). "Sioux, Assiniboine, and Stoney Dialects: A Classification". Anthropological Linguistics vol. 34, nos. 1-4

- Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L. (2001). "The Siouan languages". In Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94–114). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Riggs, S.R., & Dorsey, J.O. (Ed.). (1973). Dakota grammar, texts, and ethnography. Minneapolis: Ross & Haines, Inc.

- Robinson, D. (1956). A history of the Dakota or Sioux Indians: from their earliest traditions and first contact with white men to the final settlement of the last of them upon reservations and the consequent abandonment of the old tribal life. Minneapolis: Ross & Haines, Inc.

- Rood, David S.; & Taylor, Allan R. (1996). "Sketch of Lakhota, a Siouan language". In Handbook of North American Indians: Languages (Vol. 17, pp. 440–482). Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution.

- Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Center. Our languages: Dakota Lakota Nakota. Retrieved November 30, 2008. Web site: [3]

- Shaw, P.A. (1980). Theoretical issues in Dakota phonology and morphology. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc.

- Utley, R.M. (1963). The last days of the Sioux nation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

External links

- Lakota Language Reclamation Project - "Open sourcing the People's language for all Lakota and Dakota people and our allies"

- Our Languages: Dakota, Nakota, Lakota (Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Centre)

- Red Cloud Indian School Lakota Language Project