The Faerie Queene

| The Faerie Queene | |

|---|---|

| by Edmund Spenser | |

Title page of The Faerie Queene, circa 1590 | |

| Country | Kingdom of England |

| Language | Early Modern English |

| Genre(s) | Epic poem |

| Publication date | 1590, 1596 |

| Lines | Over 36,000 |

| Metre | Spenserian stanza |

The Faerie Queene is an English epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books I–III were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 together with books IV–VI. The Faerie Queene is notable for its form: at over 36,000 lines and over 4,000 stanzas [1] it is one of the longest poems in the English language; it is also the work in which Spenser invented the verse form known as the Spenserian stanza.[2] On a literal level, the poem follows several knights as a means to examine different virtues, and though the text is primarily an allegorical work, it can be read on several levels of allegory, including as praise (or, later, criticism) of Queen Elizabeth I. In Spenser's "Letter of the Authors", he states that the entire epic poem is "cloudily enwrapped in Allegorical devices", and that the aim of publishing The Faerie Queene was to "fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline".[3]

Spenser presented the first three books of The Faerie Queene to Elizabeth I in 1589, probably sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh. The poem was a clear effort to gain court favour, and as a reward Elizabeth granted Spenser a pension for life amounting to £50 a year,[4] though there is no further evidence that Elizabeth I ever read any of the poem. This royal patronage elevated the poem to a level of success that made it Spenser's defining work.[5]

Summary

Book I is centred on the virtue of holiness as embodied in the Redcrosse Knight. Largely self-contained, Book I can be understood to be its own miniature epic. The Redcrosse Knight and his lady Una travel together as he fights the monster Errour, then separately after the wizard Archimago tricks the Redcrosse Knight into thinking that Una is unchaste using a false dream. After he leaves, the Redcrosse Knight meets Duessa, who feigns distress in order to entrap him. Duessa leads the Redcrosse Knight to captivity by the giant Orgoglio. Meanwhile, Una overcomes peril, meets Arthur, and finally finds the Redcrosse Knight and rescues him from his capture, from Duessa, and from Despair. Una and Arthur help the Redcrosse Knight recover in the House of Holiness, with the House's ruler Caelia and her three daughters joining them; there the Redcrosse Knight sees a vision of his future. He then returns Una to her parents' castle and rescues them from a dragon, and the two are betrothed after resisting Archimago one last time.

Book II is centred on the virtue of Temperance as embodied in Sir Guyon, who is tempted by the fleeing Archimago into nearly attacking the Redcrosse Knight. Guyon discovers a woman killing herself out of grief for having her lover tempted and bewitched by the witch Acrasia and killed. Guyon swears a vow to avenge them and protect their child. Guyon on his quest starts and stops fighting several evil, rash, or tricked knights and meets Arthur. Finally, they come to Acrasia's Island and the Bower of Bliss, where Guyon resists temptations to violence, idleness, and lust. Guyon captures Acrasia in a net, destroys the Bower, and rescues those imprisoned there.

Book III is centred on the virtue of Chastity as embodied in Britomart, a lady knight. Resting after the events of Book II, Guyon and Arthur meet Britomart, who wins a joust with Guyon. They separate as Arthur and Guyon leave to rescue Florimell, while Britomart rescues the Redcrosse Knight. Britomart reveals to the Redcrosse Knight that she is pursuing Sir Artegall because she is destined to marry him. The Redcrosse Knight defends Artegall and they meet Merlin, who explains more carefully Britomart's destiny to found the English monarchy. Britomart leaves and fights Sir Marinell. Arthur looks for Florimell, joined later by Sir Satyrane and Britomart, and they witness and resist sexual temptation. Britomart separates from them and meets Sir Scudamore, looking for his captured lady Amoret. Britomart alone is able to rescue Amoret from the wizard Busirane. Unfortunately, when they emerge from the castle Scudamore is gone. (The 1590 version with Books I–III depicts the lovers' happy reunion, but this was changed in the 1596 version which contained all six books.)

Book IV, despite its title "The Legend of Cambell and Telamond or Of Friendship", Cambell's companion in Book IV is actually named Triamond, and the plot does not center on their friendship; the two men appear only briefly in the story. The book is largely a continuation of events begun in Book III. First, Scudamore is convinced by the hag Ate (discord) that Britomart has run off with Amoret and becomes jealous. A three-day tournament is then held by Satyrane, where Britomart beats Arthegal (both in disguise). Scudamore and Arthegal unite against Britomart, but when her helmet comes off in battle Arthegal falls in love with her. He surrenders, removes his helmet, and Britomart recognizes him as the man in the enchanted mirror. Arthegal pledges his love to her but must first leave and complete his quest. Scudamore, upon discovering Britomart's sex, realizes his mistake and asks after his lady, but by this time Britomart has lost Amoret, and she and Scudamore embark together on a search for her. The reader discovers that Amoret was abducted by a savage man and is imprisoned in his cave. One day Amoret darts out past the savage and is rescued from him by the squire Timias and Belphoebe. Arthur then appears, offering his service as a knight to the lost woman. She accepts, and after a couple of trials on the way, Arthur and Amoret finally happen across Scudamore and Britomart. The two lovers are reunited. Wrapping up a different plotline from Book III, the recently recovered Marinel discovers Florimell suffering in Proteus' dungeon. He returns home and becomes sick with love and pity. Eventually he confesses his feelings to his mother, and she pleads with Neptune to have the girl released, which the god grants.

Book V is centred on the virtue of Justice as embodied in Sir Artegall.

Book VI is centred on the virtue of Courtesy as embodied in Sir Calidore.

Major characters

- Acrasia, seductress of knights. Guyon destroys her Bower of Bliss at the end of Book 2. Similar characters in other epics: Circe (Homer's Odyssey), Alcina (Ariosto), Armida (Tasso), or the fairy woman from Keats' poem "La Belle Dame sans Merci".

- Amoret(ta), the betrothed of Scudamour, kidnapped by Busirane on her wedding night, saved by Britomart. She represents the virtue of married love, and her marriage to Scudamour serves as the example that Britomart and Artegall seek to copy. Amoret and Scudamor are separated for a time by circumstances, but remain loyal to each other until they (presumably) are reunited.

- Archimago, an evil sorcerer who is sent to stop the knights in the service of the Faerie Queene. Of the knights, Archimago hates Redcrosse most of all, hence he is symbolically the nemesis of England.

- Artegall (or Artegal or Arthegal or Arthegall), a knight who is the embodiment and champion of Justice. He meets Britomart after defeating her in a sword fight (she had been dressed as a knight) and removing her helmet, revealing her beauty. Artegall quickly falls in love with Britomart. Artegall has a companion in Talus, a metal man who wields a flail and never sleeps or tires but will mercilessly pursue and kill any number of villains. Talus obeys Artegall's command, and serves to represent justice without mercy (hence, Artegall is the more human face of justice). Later, Talus does not rescue Artegall from enslavement by the wicked slave-mistress Radigund, because Artegall is bound by a legal contract to serve her. Only her death, at Britomart's hands, liberates him. Chrysaor was the golden sword of Sir Artegall. This sword was also the favorite weapon of Demeter, the Greek goddess of the harvest. Because it was "Tempred with Adamant", it could cleave through anything.

- Arthur of the Round Table, but playing a different role here. He is madly in love with the Faerie Queene and spends his time in pursuit of her when not helping the other knights out of their sundry predicaments. Prince Arthur is the Knight of Magnificence, the perfection of all virtues.

- Ate, a fiend from Hell disguised as a beautiful maiden. Ate opposes Book IV's virtue of friendship through spreading discord. She is aided in her task by Duessa, the female deceiver of Book I, whom Ate summoned from Hell. Ate and Duessa have fooled the false knights Blandamour and Paridell into taking them as lovers. Her name is possibly inspired by the Greek goddess of misfortune Atë, said to have been thrown from Heaven by Zeus, similar to the fallen angels.

- Belphoebe, the beautiful sister of Amoret who spends her time in the woods hunting and avoiding the numerous amorous men who chase her. Timias, the squire of Arthur, eventually wins her love after she tends to the injuries he sustained in battle; however, Timias must endure much suffering to prove his love when Belphoebe sees him tending to a wounded woman and, misinterpreting his actions, flies off hastily. She is only drawn back to him after seeing how he has wasted away without her.

- Britomart, a female knight, the embodiment and champion of Chastity. She is young and beautiful, and falls in love with Artegall upon first seeing his face in her father's magic mirror. Though there is no interaction between them, she travels to find him again, dressed as a knight and accompanied by her nurse, Glauce. Britomart carries an enchanted spear that allows her to defeat every knight she encounters, until she loses to a knight who turns out to be her beloved Artegall. (Parallel figure in Ariosto: Bradamante.) Britomart is one of the most important knights in the story. She searches the world, including a pilgrimage to the shrine of Isis, and a visit with Merlin the magician. She rescues Artegall, and several other knights, from the evil slave-mistress Radigund. Furthermore, Britomart accepts Amoret at a tournament, refusing the false Florimell.

- Busirane, the evil sorcerer who captures Amoret on her wedding night. When Britomart enters his castle to defeat him, she finds him holding Amoret captive. She is bound to a pillar and Busirane is torturing her. The clever Britomart handily defeats him and returns Amoret to her husband.

- Caelia, the ruler of the House of Holiness.

- Calidore, the Knight of Courtesy, hero of Book VI. He is on a quest from the Faerie Queene to slay the Blatant Beast.

- Cambell, one of the Knights of Friendship, hero of Book IV. Brother of Canacee and friend of Triamond.

- Cambina, daughter of Agape and sister to Priamond, Diamond, and Triamond. Cambina is depicted holding a caduceus and a cup of nepenthe, signifying her role as a figure of concord. She marries Cambell after bringing an end to his fight with Triamond.

- Colin Clout, a shepherd noted for his songs and bagpipe playing, briefly appearing in Book VI. He is the same Colin Clout as in Spenser's pastoral poetry, which is fitting because Calidore is taking a sojourn into a world of pastoral delight, ignoring his duty to hunt the Blatant Beast, which is why he set out to Ireland to begin with. Colin Clout may also be said to be Spenser himself.

- Cymochles, a knight in Book II who is defined by indecision and fluctuations of the will. He and his fiery brother Pyrochles represent emotional maladies that threaten temperance. The two brothers are both slain by Prince Arthur in Canto VIII.

- Chrysogonee, mother of Belphoebe and her twin Amoretta. She hides in the forest and, becoming tired, falls asleep on a bank, where she is impregnated by sunbeams and gives birth to twins. The goddesses Venus and Diana find the newborn twins and take them: Venus takes Amoretta and raises her in the Garden of Adonis, and Diana takes Belphoebe.

- Despair, a distraught man in a cave, his name coming from his mood. Using just rhetoric, he nearly persuades Redcrosse Knight to commit suicide, before Una steps in.

- Duessa, a lady who personifies Falsehood in Book I, known to Redcrosse as "Fidessa". As the opposite of Una, she represents the "false" religion of the Roman Catholic Church. She is also initially an assistant, or at least a servant, to Archimago.

- Florimell, a lady in love with the knight Marinell, who initially rejects her. Hearing that he has been wounded, she sets out to find him and faces various perils, culminating in her capture by the sea god Proteus. She is reunited with Marinell at the end of Book IV, and is married to him in Book V.

- Guyon, the Knight of Temperance, the hero of Book II. He is the leader of the Knights of Maidenhead and carries the image of Gloriana on his shield. According to the Golden Legend, St. George's name shares etymology with Guyon, which specifically means "the holy wrestler".

- Marinell, "the knight of the sea"; son of a water nymph, he avoided all love because his mother had learnt that a maiden was destined to do him harm; this prophecy was fulfilled when he was stricken down in battle by Britomart, though he was not mortally wounded.

- Orgoglio, an evil giant. His name means "pride" in Italian.

- The Redcrosse Knight, hero of Book I. Introduced in the first canto of the poem, he bears the emblem of Saint George, patron saint of England; a red cross on a white background that is still the flag of England. The Redcrosse Knight is declared the real Saint George in Canto X. He also learns that he is of English ancestry, having been stolen by a Fay and raised in Faerieland. In the climactic battle of Book I, Redcrosse slays the dragon that has laid waste to Eden. He marries Una at the end of Book I, but brief appearances in Books II and III show him still questing through the world.

- Satyrane, a wild half-satyr man raised in the wild and the epitome of natural human potential. Tamed by Una, he protects her, but ends up locked in a battle against the chaotic Sansloy, which remains unconcluded. Satyrane finds Florimell's girdle, which she drops while flying from a beast. He holds a three-day tournament for the right to possess the girdle. His Knights of Maidenhead win the day with Britomart's help.

- Scudamour, the lover of Amoret. His name means "shield of love". This character is based on Sir James Scudamore, a jousting champion and courtier to Queen Elizabeth I. Scudamour loses his love Amoret to the sorcerer Busirane. Though the 1590 edition of The Faerie Queene has Scudamour united with Amoret through Britomart's assistance, the continuation in Book IV has them separated, never to be reunited.

- Talus, an "iron man" who helps Arthegall to dispense justice in Book V. The name is likely from Latin "talus" (ankle) with reference to that which justice "stands on," and perhaps also to the ankle of Achilles, who was otherwise invincible, or the mythological bronze man Talos.

- Triamond, one of the Knights of Friendship, a hero of Book IV. Friend of Cambell. One of three brothers; when Priamond and Diamond died, their souls joined with his body. After battling Cambell, Triamond marries Cambell's sister, Canacee.

- Una, the personification of the "True Church". She travels with the Redcrosse Knight (who represents England), whom she has recruited to save her parents' castle from a dragon. She also defeats Duessa, who represents the "false" (Catholic) church and the person of Mary, Queen of Scots, in a trial reminiscent of that which ended in Mary's beheading. Una is also representative of Truth.

Themes

Allegory of virtue

A letter written by Spenser to Sir Walter Raleigh in 1590[6] contains a preface for The Faerie Queene, in which Spenser describes the allegorical presentation of virtues through Arthurian knights in the mythical "Faerieland". Presented as a preface to the epic in most published editions, this letter outlines plans for twenty-four books: twelve based each on a different knight who exemplified one of twelve "private virtues", and a possible twelve more centred on King Arthur displaying twelve "public virtues". Spenser names Aristotle as his source for these virtues, though the influences of Thomas Aquinas and the traditions of medieval allegory can be observed as well.[7] It is impossible to predict how the work would have looked had Spenser lived to complete it, since the reliability of the predictions made in his letter to Raleigh is not absolute, as numerous divergences from that scheme emerged as early as 1590 in the first Faerie Queene publication.

In addition to the six virtues Holiness, Temperance, Chastity, Friendship, Justice, and Courtesy, the Letter to Raleigh suggests that Arthur represents the virtue of Magnificence, which ("according to Aristotle and the rest") is "the perfection of all the rest, and containeth in it them all"; and that the Faerie Queene herself represents Glory (hence her name, Gloriana). The unfinished seventh book (the Cantos of Mutability) appears to have represented the virtue of "constancy."

Religion

The Faerie Queene was written during the Reformation, a time of religious and political controversy. After taking the throne following the death of her half-sister Mary, Elizabeth changed the official religion of the nation to Protestantism.[8] The plot of book one is similar to Foxe's Book of Martyrs, which was about the persecution of the Protestants and how Catholic rule was unjust.[9] Spenser includes the controversy of Elizabethan church reform within the epic. Gloriana has godly English knights destroy Catholic continental power in Books I and V.[10] Spenser also endows many of his villains with "the worst of what Protestants considered a superstitious Catholic reliance on deceptive images".[11]

Politics

The poem celebrates, memorializes, and critiques the House of Tudor (of which Elizabeth was a part), much as Virgil's Aeneid celebrates Augustus's Rome. The Aeneid states that Augustus descended from the noble sons of Troy; similarly, The Faerie Queene suggests that the Tudor lineage can be connected to King Arthur. The poem is deeply allegorical and allusive; many prominent Elizabethans could have found themselves partially represented by one or more of Spenser's figures. Elizabeth herself is the most prominent example. She appears in the guise of Gloriana, the Faerie Queen, but also in Books III and IV as the virgin Belphoebe, daughter of Chrysogonee and twin to Amoret, the embodiment of womanly married love. Perhaps also, more critically, Elizabeth is seen in Book I as Lucifera, the "maiden queen" whose brightly lit Court of Pride masks a dungeon full of prisoners.[citation needed]

The poem also displays Spenser's thorough familiarity with literary history. The world of The Faerie Queene is based on English Arthurian legend, but much of the language, spirit, and style of the piece draw more on Italian epic, particularly Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso and Torquato Tasso's Jerusalem Delivered.[12] Book V of The Faerie Queene, the Book of Justice, is Spenser's most direct discussion of political theory. In it, Spenser attempts to tackle the problem of policy toward Ireland and recreates the trial of Mary, Queen of Scots.[13]

Archetypes

Some literary works sacrifice historical context to archetypal myth, reducing poetry to Biblical quests, whereas Spenser reinforces the actuality of his story by adhering to archetypal patterns.[14] Throughout The Faerie Queene, Spenser does not concentrate on a pattern "which transcends time" but "uses such a pattern to focus the meaning of the past on the present".[14] By reflecting on the past, Spenser achieves ways of stressing the importance of Elizabeth's reign. In turn, he does not "convert event into myth" but "myth into event".[14] Within The Faerie Queene, Spenser blurs the distinction between archetypal and historical elements deliberately. For example, Spenser probably does not believe in the complete truth of the British Chronicle, which Arthur reads in the House of Alma.[14] In this instance, the Chronicle serves as a poetical equivalent for factual history. Even so, poetical history of this kind is not myth; rather, it "consists of unique, if partially imaginary, events recorded in chronological order".[14] The same distinction resurfaces in the political allegory of Books I and V. However, the reality to interpreted events becomes more apparent when the events occurred nearer to the time when the poem was written.[14]

Symbolism and allusion

Throughout The Faerie Queene, Spenser creates "a network of allusions to events, issues, and particular persons in England and Ireland" including Mary, Queen of Scots, the Spanish Armada, the English Reformation, and even the Queen herself.[15] It is also known that James VI of Scotland read the poem, and was very insulted by Duessa – a very negative depiction of his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots.[16] The Faerie Queene was then banned in Scotland. This led to a significant decrease in Elizabeth's support for the poem.[16] Within the text, both the Faerie Queene and Belphoebe serve as two of the many personifications of Queen Elizabeth, some of which are "far from complimentary".[15]

Though it praises her in some ways, The Faerie Queene questions Elizabeth's ability to rule so effectively because of her gender, and also inscribes the "shortcomings" of her rule.[17] There is a character named Britomart who represents married chastity. This character is told that her destiny is to be an "immortal womb" – to have children.[17] Here, Spenser is referring to Elizabeth's unmarried state and is touching on anxieties of the 1590s about what would happen after her death since the kingdom had no heir.[17]

The Faerie Queene's original audience would have been able to identify many of the poem's characters by analyzing the symbols and attributes that spot Spenser's text. For example, readers would immediately know that "a woman who wears scarlet clothes and resides along the Tiber River represents the Roman Catholic Church".[15] However, marginal notes jotted in early copies of The Faerie Queene suggest that Spenser's contemporaries were unable to come to a consensus about the precise historical referents of the poem's "myriad figures".[15] In fact, Sir Walter Raleigh's wife identified many of the poem's female characters as "allegorical representations of herself".[15] Other symbols prevalent in The Faerie Queene are the numerous animal characters present in the poem. They take the role of "visual figures in the allegory and in illustrative similes and metaphors".[18] Specific examples include the swine present in Lucifera's castle who embodied gluttony, and Duessa, the deceitful crocodile who may represent Mary, Queen of Scots, in a negative light.[citation needed]

The House of Busirane episode in Book III in The Faerie Queene is partially based on an early modern English folktale called "Mr. Fox's Mottos". In the tale, a young woman named Lady Mary has been enticed by Mr. Fox, who resembles Bluebeard in his manner of killing his wives. She defeats Mr. Fox and tells about his deeds. Notably, Spenser quotes the story as Britomart makes her way through the House, with warning mottos above each doorway "Be bold, be bold, but not too bold".[19]

Composition

Spenser's intentions

While writing his poem, Spenser strove to avoid "gealous opinions and misconstructions" because he thought it would place his story in a "better light" for his readers.[20] Spenser stated in his letter to Raleigh, published with the first three books,[17] that "the general end of the book is to fashion a gentleman or noble person in virtuous and gentle discipline".[20] Spenser considered his work "a historical fiction" which men should read for "delight" rather than "the profit of the ensample".[20] The Faerie Queene was written for Elizabeth to read and was dedicated to her. However, there are dedicatory sonnets in the first edition to many powerful Elizabethan figures.[21]

Spenser addresses "lodwick" in Amoretti 33, when talking about The Faerie Queene still being incomplete. This could be either his friend Lodowick Bryskett or his long deceased Italian model Ludovico Ariosto, whom he praises in "Letter to Raleigh".[22]

Dedication

The poem is dedicated to Elizabeth I who is represented in the poem as the Faerie Queene Gloriana, as well as the character Belphoebe.[23] Spenser prefaces the poem with sonnets additionally dedicated to Sir Christopher Hatton, Lord Burleigh, the Earl of Oxford, the Earl of Northumberland, the Earl of Cumberland, the Earl of Essex, the Earl of Ormond and Ossory, High Admiral Charles Howard, Lord Hunsdon, Lord Grey of Wilton, Lord Buckhurst, Sir Francis Walsingham, Sir John Norris, Sir Walter Raleigh, the Countess of Pembroke (on the subject of her brother Sir Philip Sidney), and Lady Carew.

Social commentary

In October 1589, after nine years in Ireland,[24] Spenser voyaged to England and saw the Queen. It is possible that he read to her from his manuscript at this time. On 25 February 1591, the Queen gave him a pension of fifty pounds per year.[25] He was paid in four instalments on 25 March, 24 June, 29 September, and 25 December.[26] After the first three books of The Faerie Queene were published in 1590, Spenser found himself disappointed in the monarchy; among other things, "his annual pension from the Queen was smaller than he would have liked" and his humanist perception of Elizabeth's court "was shattered by what he saw there".[27] Despite these frustrations, however, Spenser "kept his aristocratic prejudices and predispositions".[27] Book VI stresses that there is "almost no correlation between noble deeds and low birth" and reveals that to be a "noble person," one must be a "gentleman of choice stock".[27]

Throughout The Faerie Queene, virtue is seen as "a feature for the nobly born" and within Book VI, readers encounter worthy deeds that indicate aristocratic lineage.[27] An example of this is the hermit to whom Arthur brings Timias and Serena. Initially, the man is considered a "goodly knight of a gentle race" who "withdrew from public service to religious life when he grew too old to fight".[27] Here, we note the hermit's noble blood seems to have influenced his gentle, selfless behaviour. Likewise, audiences acknowledge that young Tristram "speaks so well and acts so heroically" that Calidore "frequently contributes him with noble birth" even before learning his background; in fact, it is no surprise that Tristram turns out to be the son of a king, explaining his profound intellect.[28] However, Spenser's most peculiar example of noble birth is demonstrated through the characterization of the Salvage Man. Using the Salvage Man as an example, Spenser demonstrated that "ungainly appearances do not disqualify one from noble birth".[28] By giving the Salvage Man a "frightening exterior," Spenser stresses that "virtuous deeds are a more accurate indication of gentle blood than physical appearance.[28]

On the opposite side of the spectrum, The Faerie Queene indicates qualities such as cowardice and discourtesy that signify low birth. During his initial encounter with Arthur, Turpine "hides behind his retainers, chooses ambush from behind instead of direct combat, and cowers to his wife, who covers him with her voluminous skirt".[29] These actions demonstrate that Turpine is "morally emasculated by fear" and furthermore, "the usual social roles are reversed as the lady protects the knight from danger.[29] Scholars believe that this characterization serves as "a negative example of knighthood" and strives to teach Elizabethan aristocrats how to "identify a commoner with political ambitions inappropriate to his rank".[29]

Poetic structure

The Faerie Queene was written in Spenserian stanza, which Spenser created specifically for The Faerie Queene. Spenser varied existing epic stanza forms, the rhyme royal used by Chaucer, with the rhyme pattern ABABBCC, and the ottava rima, which originated in Italy, with the rhyme pattern ABABABCC. Spenser's stanza is the longest of the three, with nine iambic lines – the first eight of them five footed, that is, pentameters, and the ninth six footed, that is, a hexameter, or Alexandrine – which form "interlocking quatrains and a final couplet".[30] The rhyme pattern is ABABBCBCC. Over two thousand stanzas were written for the 1590 Faerie Queene.[30] Many see Spenser's purposeful use of archaic language as an intentional means of aligning himself with Chaucer and placing himself within a trajectory of building English national literary history.

Theological structure

In Elizabethan England, no subject was more familiar to writers than theology. Elizabethans learned to embrace religious studies in petty school, where they "read from selections from the Book of Common Prayer and memorized Catechisms from the Scriptures".[31] This influence is evident in Spenser's text, as demonstrated in the moral allegory of Book I. Here, allegory is organized in the traditional arrangement of Renaissance theological treatises and confessionals. While reading Book I, audiences first encounter original sin, justification and the nature of sin before analysing the church and the sacraments.[32] Despite this pattern, Book I is not a theological treatise; within the text, "moral and historical allegories intermingle" and the reader encounters elements of romance.[33] However, Spenser's method is not "a rigorous and unyielding allegory," but "a compromise among conflicting elements".[33] In Book I of The Faerie Queene the discussion of the path to salvation begins with original sin and justification, skipping past initial matters of God, the Creeds, and Adam's fall from grace.[33] This literary decision is pivotal because these doctrines "center the fundamental theological controversies of the Reformation".[33]

Sources

Myth and history

During The Faerie Queene's inception, Spenser worked as a civil servant, in "relative seclusion from the political and literary events of his day".[34] As Spenser laboured in solitude, The Faerie Queene manifested within his mind, blending his experiences into the content of his craft. Within his poem, Spenser explores human consciousness and conflict, relating to a variety of genres including sixteenth century Arthurian literature.[35] The Faerie Queene was influenced strongly by Italian works, as were many other works in England at that time. The Faerie Queene draws heavily on Ariosto and Tasso.[36]

The first three books of The Faerie Queene operate as a unit, representing the entire cycle from the fall of Troy to the reign of Elizabeth.[35] Using in medias res, Spenser introduces his historical narrative at three different intervals, using chronicle, civil conversation, and prophecy as its occasions.[35]

Despite the historical elements of his text, Spenser is careful to label himself a historical poet as opposed to a historiographer. Spenser notes this differentiation in his letter to Raleigh, noting "a Historiographer discourseth of affairs orderly as they were done ... but a Poet thrusteth into the midst ... and maketh a pleasing Analysis of all".[37]

Spenser's characters embody Elizabethan values, highlighting political and aesthetic associations of Tudor Arthurian tradition in order to bring his work to life. While Spenser respected British history and "contemporary culture confirmed his attitude",[37] his literary freedom demonstrates that he was "working in the realm of mythopoeic imagination rather than that of historical fact".[37] In fact, Spenser's Arthurian material serves as a subject of debate, intermediate between "legendary history and historical myth" offering him a range of "evocative tradition and freedom that historian's responsibilities preclude".[38] Concurrently, Spenser adopts the role of a sceptic, reflected in the way in which he handles the British history, which "extends to the verge of self-satire".[39]

Medieval subject matter

The Faerie Queene owes, in part, its central figure, Arthur, to a medieval writer, Geoffrey of Monmouth. In his Prophetiae Merlini ("Prophecies of Merlin"), Geoffrey's Merlin proclaims that the Saxons will rule over the Britons until the "Boar of Cornwall" (Arthur) again restores them to their rightful place as rulers.[40] The prophecy was adopted by the Welsh and eventually used by the Tudors. Through their ancestor, Owen Tudor, the Tudors had Welsh blood, through which they claimed to be descendants of Arthur and rightful rulers of Britain.[41] The tradition begun by Geoffrey of Monmouth set the perfect atmosphere for Spenser's choice of Arthur as the central figure and natural bridegroom of Gloriana.

Reception

Diction

Since its inception four centuries ago, Spenser's diction has been scrutinized by scholars. Despite the enthusiasm the poet and his work received, Spenser's experimental diction was "largely condemned" before it received the acclaim it has today.[42] Seventeenth-century philologists such as Davenant considered Spenser's use of "obsolete language" as the "most vulgar accusation that is laid to his charge".[43] Scholars have recently observed that the classical tradition tucked within The Faerie Queene is related to the problem of his diction because it "involves the principles of imitation and decorum".[44] Despite these initial criticisms, Spenser is "now recognized as a conscious literary artist" and his language is deemed "the only fitting vehicle for his tone of thought and feelings".[44] Spenser's use of language was widely contrasted to that of "free and unregulated" sixteenth-century Shakespearian grammar.[45] Spenser's style is standardized, lyrically sophisticated, and full of archaisms that give the poem an original taste. Sugden argues in The Grammar of Spenser's Faerie Queene that the archaisms reside "chiefly in vocabulary, to a high degree in spelling, to some extent in the inflexions, and only slightly in the syntax".[45]

Samuel Johnson also commented critically on Spenser's diction, with which he became intimately acquainted during his work on A Dictionary of the English Language, and "found it a useful source for obsolete and archaic words"; Johnson, however, mainly considered Spenser's (early) pastoral poems, a genre of which he was not particularly fond.[46]

The diction and atmosphere of The Faerie Queene relied on much more than just Middle English; for instance, classical allusions and classical proper names abound—especially in the later books—and he coined some names based on Greek, such as "Poris" and "Phao lilly white."[47] Classical material is also alluded to or reworked by Spenser, such as the rape of Lucretia, which was reworked into the story of the character Amavia in Book Two.[48]

Language

Spenser's language in The Faerie Queene, as in The Shepheardes Calender, is deliberately archaic, though the extent of this has been exaggerated by critics who follow Ben Jonson's dictum, that "in affecting the ancients Spenser writ no language."[49] Allowing that Jonson's remark may only apply to the Calendar, Bruce Robert McElderry Jr. states, after a detailed investigation of The Faerie Queene's diction, that Jonson's statement "is a skillful epigram; but it seriously misrepresents the truth if taken at anything like its face value".[50] The number of archaisms used in the poem is not overwhelming—one source reports thirty-four in Canto I of Book I, that is, thirty-four words out of a total forty-two hundred words, less than one percent.[51] According to McElderry, language does not account for the poem's archaic tone: "The subject-matter of The Faerie Queene is itself the most powerful factor in creating the impression of archaism."[52]

Examples of medieval archaisms (in morphology and diction) include:

- Infinitive in -en: vewen 1. 201, 'to view';

- Prefix y- retained in participle: yclad, 1. 58, 254, 'clad, clothed';

- Adjective: combrous, 1. 203, 'harassing, troublesome';

- Verb: keepe, 1. 360, 'heed, give attention to'.[51]

Adaptation and derivative works

Numerous adaptations in the form of children's literature have been made – the work was a popular choice in the 19th and early 20th century with over 20 different versions written, with the earliest being E. W. Bradburn's Legends from Spencer's Fairy Queen, for Children (1829), written in the form of a dialogue between mother and children – the 19th-century versions oft concentrated on the moral aspect of the tale.[53] In terms of the English-speaking world adaptions of the work were relatively more popular in the United Kingdom than in the United States compared to contemporary works like Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, presumably due to the differences in appeal of the intended audiences (Royal court vs Ordinary people) and their relative appeal to the general American readership.[54]

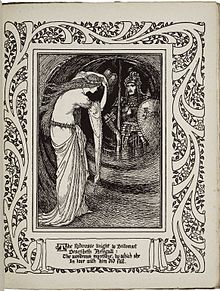

The Edwardian era was particularly rich in adaptation for children, and the works richly illustrated, with contributing artists including A. G. Walker, Gertrude Demain Hammond, T. H. Robinson, Frank C. Papé, Brinsley Le Fanu and H. J. Ford.[54] Additionally, Walter Crane illustrated a six-volume collection of the complete work, published 1897, considered a great example of the Arts and Crafts movement.[55][56]

In "The Mathematics of Magic", the second of Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp's Harold Shea stories, the modern American adventurers Harold Shea and Reed Chalmers visit the world of The Faerie Queene, where they discover that the greater difficulties faced by Spenser's knights in the later portions of the poem are explained by the evil enchanters of the piece having organized a guild to more effectively oppose them. Shea and Chalmers reveal this conspiracy to the knights and assist in its overthrow. In the process, Belphebe and Florimel of Faerie become respectively the wives of Shea and Chalmers and accompany them on further adventures in other worlds of myth and fantasy.

A considerable part of Elizabeth Bear's "Promethean Age" series [57] takes place in a Kingdom of Faerie which is loosely based on the one described by Spenser. As depicted by Bear, Spenser was aware of this Kingdom's existence and his work was actually a description of fact rather than invented fantasy; Queen Elizabeth I had a secret pact of mutual help with the Queen of Faerie; and such historical characters as Christopher Marlowe and William Shakespeare visited Faerie and had adventures there.

According to Richard Simon Keller, George Lucas's Star Wars film also contains elements of a loose adaptation, as well as being influenced by other works, with parallels including the story of the Red Cross Knight championing Una against the evil Archimago in the original compared with Lucas's Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia, and Darth Vader. Keller sees extensive parallels between the film and book one of Spenser's work, stating "[A]lmost everything of importance that we see in the Star Wars movie has its origin in The Faerie Queene, from small details of weaponry and dress to large issues of chivalry and spirituality".[58]

References in popular culture

The Netflix series The Crown references The Faerie Queene and Gloriana in season 1 episode 10, entitled "Gloriana". In the final scene, Queen Elizabeth II, portrayed by Claire Foy, is being photographed. Prompting Her Majesty's poses, Cecil Beaton says:

"All hail sage Lady, whom a grateful Isle hath blessed."[59] Not moving, not breathing. Our very own goddess. Glorious Gloriana. Forgetting Elizabeth Windsor now. Now only Elizabeth Regina. Yes.[60]

Near the end of the 1995 adaptation of Sense and Sensibility, Colonel Brandon reads The Faerie Queene aloud to Marianne Dashwood.

Quotes from the poem are used as epigraphs in Troubled Blood by Robert Galbraith, a pen name of J. K. Rowling.

In the Thursday Next series by Jasper Fforde, Granny Next (who is an older version of Thursday Next herself) is condemned to reading the “ten most boring classics” before she can die. She finally passes away after reading The Faerie Queene.

See also

References

- ^ Wilkinson, Hazel (30 November 2017). Edmund Spenser and the Eighteenth-Century Book. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 9781107199552. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Loewenstein & Mueller 2003, p. 369.

- ^ Spenser 1984, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Kaske, Carol V., ed. (2006). Spenser's The Faerie Queene Book One. Indianapolis: Hackett. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-87220-808-7.

- ^ Roche 1984, p. 11.

- ^ Roche 1984, p. 1070: "The date of the letter—23 January 1589—is actually 1590, since England did not adopt the Gregorian calendar until 1752 and the dating of the new year began on 25 March, Lady Day"

- ^ Tuve 1966.

- ^ Greenblatt 2006, p. 687.

- ^ McCabe 2010, p. 41.

- ^ Heale 1999, p. 8.

- ^ McCabe 2010, p. 39.

- ^ Abrams 2000, p. 623.

- ^ McCabe, Richard (Spring 1987). "The Masks of Duessa: Spenser, Mary Queen of Scots, and James VI". English Literary Renaissance. 17 (2): 224–242. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6757.1987.tb00934.x. S2CID 130980896 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d e f Gottfried 1968, p. 1363.

- ^ a b c d e Greenblatt 2012, p. 775.

- ^ a b McCabe 2010, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d Heale 1999, p. 11.

- ^ Marotti 1965, p. 69.

- ^ Micros 2008.

- ^ a b c Spenser 1984, p. 15.

- ^ McCabe 2010, p. 50.

- ^ McCabe 2010, p. 273.

- ^ Spenser 1984, p. 16: "In that Faery Queene I meane glory in my generall person of our soueraine the Queene, and her kingdome in Faery land ... For considering she beareth two persons, the one of a most royall Queene or Empresse, the other of a most vertuous and beautifull Lady, this latter part in some places I doe expresse in Belphoebe"

- ^ Oram, William A. (2003). "Spenser's Audiences, 1589–91". Studies in Philology. 100 (4): 514–533. doi:10.1353/sip.2003.0019. JSTOR 4174771. S2CID 163052682.

- ^ McCabe 2010, p. 112.

- ^ McCabe 2010, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Green 1974, p. 389.

- ^ a b c Green 1974, p. 390.

- ^ a b c Green 1974, p. 392.

- ^ a b McCabe 2010, p. 213.

- ^ Whitaker 1952, p. 151.

- ^ Whitaker 1952, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d Whitaker 1952, p. 154.

- ^ Craig 1972, p. 520.

- ^ a b c Craig 1972, p. 522.

- ^ Heale 1999, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Craig 1972, p. 523.

- ^ Craig 1972, p. 524.

- ^ Craig 1972, p. 555.

- ^ Geoffrey of Monmouth.

- ^ Millican 1932.

- ^ Pope 1926, p. 575.

- ^ Pope 1926, p. 576.

- ^ a b Pope 1926, p. 580.

- ^ a b Cumming 1937, p. 6.

- ^ Turnage 1970, p. 567.

- ^ Draper 1932, p. 97.

- ^ Cañadas 2007, p. 386.

- ^ McElderry 1932, p. 144.

- ^ McElderry 1932, p. 170.

- ^ a b Parker 1925, p. 85.

- ^ McElderry 1932, p. 159.

- ^ Hamilton, Albert Charles, ed. (1990), "The Faerie Queene, children's versions", The Spenser Encyclopedia, University of Toronto Press, pp. 289–

- ^ a b Bourgeois Richmond, Velma (2016), The Faerie Queene as Children's Literature: Victorian and Edwardian Retellings in Words and Pictures, McFarland and Company, Preface, p.1-4

- ^ "THE CAT'S OUT OF THE BAG : WALTER CRANE'S FAERIE QUEENE, 1897", www.library.unt.edu

- ^ Keane, Eleanor (24 April 2013), "Featured Book: Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene", The Courtauld Institute of Art (Book Library Blog)

- ^ Monette, Sarah. "An Interview with Elizabeth Bear, conducted by Sarah Monette". Subterranean Press. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ Keller Simon, Richard (1999), "4. Star Wars and the Faerie Queen", Trash Culture : Popular Culture and the Great Tradition, University of California Press, pp. 29–37

- ^ William Wordsworth, Ecclesiastical Sonnets, XXXVIII.

- ^ "The Crown (2016) s01e10 Episode Script | SS". Springfield! Springfield!. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

Bibliography

- Abrams, M. H., ed. (2000), Norton Anthology of English Literature (7th ed.), New York: Norton

- Black, Joseph, ed. (2007), The Broadview Anthology of British Literature, vol. A (concise ed.), Broadview Press, ISBN 978-1-55111-868-0

- Cañadas, Ivan (2007), "The Faerie Queene, II.i-ii: Amavia, Medina, and the Myth of Lucretia" (PDF), Medieval and Early Modern English Studies, 15 (2): 383–94, doi:10.17054/memes.2007.15.2.383, retrieved 15 March 2016

- Craig, Joanne (1972), "The Image of Mortality: Myth and History in the Faerie Queene", ELH, 39 (4): 520–544, doi:10.2307/2872698, JSTOR 2872698

- Cumming, William Paterson (1937), "The Grammar of Spenser's Faerie Queene by Herbert W. Sugden", South Atlantic Bulletin, 3 (1): 6, doi:10.2307/3197672, JSTOR 3197672

- Davis, Walter (2002), "Spenser and the History of Allegory", English Literary Renaissance, 32 (1): 152–167, doi:10.1111/1475-6757.00006, S2CID 143462583

- Draper, John W. (1932), "Classical Coinage in the Faerie Queene", PMLA, 47 (1): 97–108, doi:10.2307/458021, JSTOR 458021, S2CID 163456548

- Glazier, Lyle (1950), "The Struggle between Good and Evil in the First Book of The Faerie Queene", College English, 11 (7): 382–387, doi:10.2307/586023, JSTOR 586023

- Gottfried, Rudolf B. (1968), "Our New Poet: Archetypal Criticism and The Faerie Queene", PMLA, 83 (5): 1362–1377, doi:10.2307/1261309, JSTOR 1261309, S2CID 163320376

- Green, Paul D. (1974), "Spenser and the Masses: Social Commentary in The Faerie Queene", Journal of the History of Ideas, 35 (3): 389–406, doi:10.2307/2708790, JSTOR 2708790

- Greenblatt, Stephen, ed. (2012), "The Faerie Queene, Introduction", The Norton Anthology of English Literature (9th ed.), London: Norton, p. 775

- Greenblatt, Stephen, ed. (2006), "Mary I (Mary Tudor)", The Norton Anthology of English Literature (8th ed.), New York: Norton, pp. 663–687

- Geoffrey of Monmouth, "Book VII Chapter III: The Prophecy of Merlin", Historia Regum Brittaniae, Caerleon Net

- Heale, Elizabeth (1999), The Faerie Queene: A Reader's Guide, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, pp. 8–11

- Healy, Thomas (2009), "Elizabeth I at Tilbury and Popular Culture", Literature and Popular Culture in Early Modern England, London: Ashgate, pp. 166–177

- Levin, Richard A. (1991), "The Legende of the Redcrosse Knight and Una, or of the Love of a Good Woman", SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, 31 (1): 1–24, doi:10.2307/450441, JSTOR 450441

- Loewenstein, David; Mueller, Janel M (2003), The Cambridge history of early modern English Literature, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-63156-4

- Marotti, Arthur F. (1965), "Animal Symbolism in the Faerie Queene: Tradition and the Poetic Context", SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, 5 (1): 69–86, doi:10.2307/449571, JSTOR 449571

- McCabe, Richard A. (2010), The Oxford Handbook of Edmund Spenser, Oxford: Oxford UP, pp. 48–273

- McElderry, Bruce Robert, Jr (March 1932), "Archaism and Innovation in Spenser's Poetic Diction", PMLA, 47 (1): 144–70, doi:10.2307/458025, JSTOR 458025, S2CID 163385153

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Micros, Marianne (2008), "Robber Bridegrooms and Devoured Brides", in Lamb, Mary Ellen; Bamford, Karen (eds.), Oral Traditions and Gender in Early Modern Literary Texts, London: Ashgate

- Millican, Charles Bowie (1932), Spenser and the Table Round, New York: Octagon

- Parker, Roscoe (1925), "Spenser's Language and the Pastoral Tradition", Language, 1 (3), Linguistic Society of America: 80–87, doi:10.2307/409365, JSTOR 409365

- Pope, Emma Field (1926), "Renaissance Criticism and the Diction of the Faerie Queene", PMLA, 41 (3): 575–580, doi:10.2307/457619, JSTOR 457619, S2CID 163503939

- Roche, Thomas P., Jr (1984), "Editorial Apparatus", The Faerie Queene, by Spenser, Edmund, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-042207-2

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: contributors list (link) - Spenser, Edmund (1984), "A Letter of the Authors Expounding His Whole Intention in the Course of the Worke: Which for That It Giueth Great Light to the Reader, for the Better Vnderstanding Is Hereunto Annexed", in Roche, Thomas P., Jr (ed.), The Fairy Queene, New York: Penguin, pp. 15–18

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Turnage, Maxine (1970). "Samuel Johnson's Criticism of the Works of Edmund Spenser". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 10 (3): 557–567. doi:10.2307/449795. ISSN 0039-3657. JSTOR 449795.

- Tuve, Rosemond (1966), Allegorical Imagery: Some Medieval Books and Their Posterity, Princeton: Princeton UP

- Wadoski, Andrew (2022), Spenser's Ethics: Empire, Mutability, and Moral Philosophy in Early Modernity, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-1-5261-6543-5

- Whitaker, Virgil K. (1952), "The Theological Structure of the Faerie Queene, Book I", ELH, 19 (3): 151–155, doi:10.2307/2871935, JSTOR 2871935

- Yamashita, Hiroshi; Suzuki, Toshiyuki (1993), A Textual Companion to The Faerie Qveene 1590, Kenyusha, Tokyo, ISBN 4-905888-05-0

- Yamashita, Hiroshi; Suzuki, Toshiyuki (1990), A Comprehensive Concordance to The Faerie Qveene 1590, Kenyusha, Tokyo, ISBN 4-905888-03-4

External links

- Macleod, Mary (1916), Stories from The Faerie Queene (retelling in prose)

- Wikisource glossary for words used in The Faerie Queene

- Summary of 'The Faerie Queene', Montclair.

- Summary of Books I–VI, Wordpress

- Faerie Queene Outline (interactive outline of Book I)

- The Faerie Queene Longman Annotated English Poets Published September 2001

Online editions

The Faerie Queene public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Faerie Queene public domain audiobook at LibriVox- Bear, Risa S., ed. (1993–96) [1882], "The Complete Works in Verse and Prose of Edmund Spenser", www.luminarium.org (HTML etext version ed.), Grosart, London

- Wise, Thomas J., ed. (1897), Spenser's Faerie queene. A poem in six books; with the fragment Mutabilitie, George Allen, in six volumes illustrated by Walter Crane

- Book I, Project Gutenberg incorporating modern rendition and glossary

- The Faerie Queene

- 1590 poems

- Anti-Catholicism in England

- Anti-Catholic publications

- Arthurian literature in English

- British poems

- Allegory

- Epic poems in English

- Fictional fairies and sprites

- Fairy royalty

- Poetry by Edmund Spenser

- Cultural depictions of Elizabeth I

- Fairies and sprites in popular culture

- Unfinished poems