Petržalka

Petržalka | |

|---|---|

Borough | |

View from Most SNP; on the left is Aupark Tower. | |

Area of Petržalka in Bratislava | |

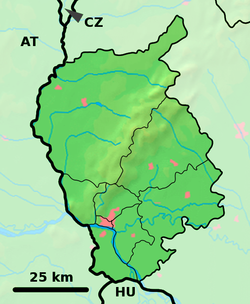

Location of Petržalka in the Bratislava Region | |

| Coordinates: 48°08′00″N 17°07′00″E / 48.13333°N 17.11667°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | |

| District | Bratislava V |

| First mentioned | 1225 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ján Hrčka |

| Area | |

• Total | 28.68 km2 (11.07 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 136 m (446 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2021) | |

• Total | 114,000 |

| • Density | 4,000/km2 (10,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 851 0X |

| Area code | +421-2 |

| Car plate | BA, BL, BT |

| Website | www |

Petržalka (Slovak pronunciation: [ˈpetr̩ʐalka]; German: Engerau / Audorf; Hungarian: Pozsonyligetfalu) is the largest borough of Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia. Situated on the right bank of the river Danube, the area shares a land border with Austria, and is home to around 100,000 people.

Names and etymology

[edit]The German name of the village Engerau (1654) derives from the ethnic name of Hungarians and comes from older placenames Mogorsciget ("Hungarian Island", 1225) and Ungerau ("Hungarian floodplain", 1509).[1] The Hungarian name, Ligetfalva, (later Pozsonyligetfalu, literally "parkland village") originates from the 1860s. After the foundation of Czechoslovakia, it was officially renamed to Petržalka (1920). The name refers to vegetables and herbs that were grown there (petržlen means "parsley").

History

[edit]

Before the 18th century, the territory of present-day Petržalka consisted of several regularly flooded islands and was not suitable for larger permanent settlement. The deed of donation of Andrew II of Hungary (1225) mentions a property Wlocendorf/Fluecendorf, abandoned village of Pechenegs and several local place names including the Peceneg Island (Beseneusciget, now national protected area Pečniansky les) and the Magyar Island (Mogorsciget). Pecheneg mercenaries on guard duty near the river Danube were probably the first permanent settlers, but the ford was protected also by other ethnic groups like Székelys and Ruthenians.[2] The abandoned village of Pecenegs (or the neighboring territory) was settled most likely by German colonists. The inhabitants of Flocendorf were ferrymen, tradesmen and farmers. In the late 15th century, a new village Ungerau/Engerau was founded. The village was inhabited mostly by Germans and Croatians fleeing from the south during the Ottoman wars.[3] During this period, the neighbouring Pressburg (Pozsony, today Bratislava) was the capital of the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary.

In the 18th century, the villages began to merge, but their population remained relatively low. It became a popular recreation area with the oldest public park in Central Europe (now Sad Janka Kráľa, founded in 1776). In 1866, the village had only 594 inhabitants and 103 houses. In 1891, it became permanently connected with Pressburg when the first railway bridge, 460 meters long, was built for the Pressburg-Csorna-Szombathely railway as the first bridge not made of wood, those wooden bridges often damaged by frost and floods. A 1910 census shows that of its 2,947 inhabitants, 1,997 spoke German, 495 spoke Hungarian, and 318 spoke Slovak as their native language.

On 1 January 1919, the Czechoslovak Legions captured Pressburg (then Bratislava). At the beginning of August, Czechoslovakia got permission to correct the borders for the strategic reasons, mainly to secure the port and to prevent a potential attack of the Hungarian Army on the town. On the night of 14 August 1919 barefoot Czechoslovak soldiers silently climbed to the Hungarian side of the bridge, captured the guards and annexed Petržalka without a fight.[4] The Paris Peace Conference finally assigned the area to Czechoslovakia with the aim of creating a bridgehead for the newly created Czechoslovak state for controlling the Danube. In the 1920s Petržalka was the largest village in Czechoslovakia.[5] During the Czechoslovak rule Petržalka grew quickly and the population increased from 3,576 (1919) to 14,164 (1930).[6] The village lost its former ethnic German majority.

Petržalka was annexed by Nazi Germany on 10 October 1938 on the basis of the Munich agreement and renamed Engerau. The Starý most bridge becomes a border bridge between the First Slovak Republic and Nazi Germany. Several thousand inhabitants of Slovak, Czech, and Hungarian ethnicity were obliged to stay in Petržalka. Although citizens of the Third Reich, their national character was repressed. The occupiers closed down all Slovak schools, and the German language replaced Slovak. Non-Germans were not allowed to participate in public life, and the Gestapo arrested citizens who promoted ideas opposing Nazism, including those active before the occupation.[7]

From November 1944 to March 1945 – Petržalka (Engerau) was the site of a labour camp for Hungarian Jews, who were deployed at the construction of the Südostwall. Out of 2000 prisoners, at least 497 died from inhumane treatment and during the death march to Bad Deutsch-Altenburg. [8][9][10]

On April 4, 1945 Petržalka was, along with the rest of Bratislava, freed from the Nazis and taken by the Communists. It was returned to Czechoslovakia after World War II. On May 5, 1945, 90% of the Hungarian population of Bratislava was forced into internment camps in Petržalka; at least 2500 Hungarians, including 71 children were murdered.[11][12][13]

On February 13, 1946 Petržalka officially became a part of Bratislava. Construction of the housing blocks known as "panelák" began in 1977.

A 2001 Census reports that of its 117,227 inhabitants, 108,600 were Slovak, 4,259 were Hungarian, 1,788 were Czech, and 219 were German.

Local parts

[edit]

Petržalka is divided into three official parts, Dvory, Lúky and Háje, and further into unofficial parts, Ovsište, Janíkov dvor, Kopčany, Zrkadlový háj, Starý háj, and Kapitulský dvor.

Characteristics

[edit]

As of 2008, Petržalka is connected to Bratislava by five bridges. It is the most densely populated residential district in Central Europe.[14]

Petržalka is primarily a residential area, with most people living in blocks of flats called paneláks, a neologism for buildings built from concrete panels joined together to form the structure, which were widely deployed throughout the Eastern Bloc during the communist era.[15] As the borough was built primarily as a residential area, it has no clearly defined centre.

Petržalka was sometimes referred to as the Bronx of Bratislava[16] because of a high crime rate and drug dealing, but as of 2008 the crime rate had become similar to that of the other boroughs.[citation needed] It has the highest suicide rate in the country.[17]

Important institutions include the congress and exposition centre Incheba and Petržalka railway station. Sad Janka Kráľa is one of the oldest municipal parks in Europe.[18] There is also the Arena Theatre, established in 1828, one of the oldest theatres in Bratislava.

Petržalka is mostly a lowland area with no hills or mountains. There are two lakes, Malý and Veľký Draždiak, which are used for swimming, fishing and leisure activities.

Education and sport

[edit]The University of Economics is based in Petržalka, with campuses situated in different locations around Bratislava.

There are 11 elementary schools and 19 kindergartens administered by the borough.[19][20] Gymnasium high schools include the state-administered Albert Einstein[21] and Pankúchova 6 gymnasiums[22] and the private Mercury Gymnasium.[23] Petržalka is also a home to Evanjelické lýceum - lutheran educational institution that played important part in development of slovak culture and national identity.[24]

The borough is also known for its football club, Artmedia Bratislava, a participant in the 2005–06 UEFA Champions League.

Transport

[edit]

Road

[edit]Petržalka is connected to the rest of Bratislava by five bridges, of which three are used for local traffic (Nový Most, Starý most and Most Apollo) and two for international traffic (Lafranconi Bridge and Prístavný most). Starý most, from the first of January 2009, was closed to all traffic except for public transport, bicycles and pedestrians.

Petržalka is located near a major international motorway junction, where the D1 and D2 motorways meet.

There is a road border crossing into Austria along Viedenska cesta near the intersection of the D1 and D2. The Austrian crossing is called Berg after the nearby town of the same name. There are no more border checks from December 21, 2007 with Slovakia joining the Schengen Area.

Railway

[edit]Bratislava-Petržalka railway station is located in the western part of the borough and is used primarily for international traffic and, since 1999, for trains to and from Vienna.[25]

Public transportation

[edit]Buses connect Petržalka with the other boroughs. In 1989, construction of a subway began, but it was stopped shortly after the Velvet Revolution broke out. Instead, a high-speed tram (light rail) line was planned but its construction was postponed multiple times because it involved a complete reconstruction of Starý most bridge. At one point it was scheduled to begin in summer 2013.[26][27][28] Test runs of trams across the bridge were carried out in February 2016.[29] Official tram operation started on 8 July 2016.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ Varsik, Branislav (1984). Z osídlenia západného a stredného Slovenska v stredoveku (in Slovak). Bratislava: Veda, vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied. p. 68.

- ^ Kačírek, Ľuboš; Tišliar, Pavol (2014a). Petržalka do roku 1918 (in Slovak). Bratislava: Muzeológia a kultúrne dedičstvo, o. z. p. 21. ISBN 978-80-971715-3-7.

- ^ Kačírek & Tišliar 2014a, p. 26.

- ^ Kačírek, Ľuboš; Tišliar, Pavol (2014b). Petržalka v rokoch 1919 – 1946 (in Slovak). Bratislava: Stimul. p. 9.

- ^ Petržalka (Zaujímavosti o mestskej časti Petržalka)

- ^ Kačírek & Tišliar 2014b, p. 26.

- ^ Occupation of Petržalka by the Nazi Germany (Okupácia Petržalky hitlerovským Nemeckom (10.10.1938 - 3.4.1945)). Jaroslav Gustafik at SME.sk.

- ^ slovak-jewish-heritage.org: Petržalka Holocaust Memorial

- ^ nachkriegsjustiz.at: Vorstellung der Dissertation von Claudia Kuretsidis-Haider (in German)

- ^ Engerau-Prozesse (review article, in German) Archived 2008-05-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Transindex" (in Hungarian). n.d. Retrieved 23 March 2008.

- ^ Dunabogdány honlapja Archived 2008-05-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "A deathcamp operated after 1945 in the area of today's Bratislava – Film about the Ligetfalu massacre". Képmás. 2020-03-27. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- ^ "Bratislava Projects at MIPIM 2007 – Petržalka City". City of Bratislava. 3 January 2007. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

Petržalka City will definitely change the face of the largest and most densely populated housing estate in Central Europe: the network of grey prefabricated buildings will be transformed into a full-fledged town with a self-contained multi-purpose centre.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (30 October 2015). "The Monoliths of Bratislava - The New York Times". The New York Times.

- ^ Shake & Slovak, The Sunday Herald, January 23, 2000

- ^ "Travel - spectator.sme.sk".

- ^ "Environment". City of Bratislava. 26 February 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ "Elementary schools directory (Adresár základných škôl)" (in Slovak). Petržalka. n.d. Archived from the original on December 29, 2005. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ "Kindergartens directory (Adresár materských škôl)" (in Slovak). Petržalka. n.d. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ Albert Einstein Gymnasium website

- ^ Pankúchova 6 Gymnasium website

- ^ Mercury Private Gymnasium website

- ^ Nosowska, Agnieszka. "K maďarskej kapitole čítanky o Pressburgu". enrs.eu. Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ^ "Bratislava - Wien complete". Railway Gazette International. 1 October 1998.

- ^ "Petržalka South City Development Area". City of Bratislava. 1 March 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ "Starý most by mohli začať rekonštruovať na jar". Slovak Newspaper SME. 16 August 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ "Starý most stále nemá povolenie". Slovak Newspaper SME. 11 January 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ "First trams cross Bratislava's Old Bridge - spectator.sme.sk". 17 February 2016.

- ^ "Sme.sk".

External links

[edit]