Vivaron

| Vivaron | |

|---|---|

| |

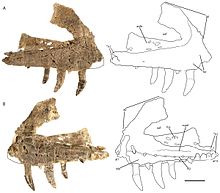

| Right maxilla of the holotype | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauria |

| Clade: | Pseudosuchia |

| Family: | †Rauisuchidae |

| Genus: | †Vivaron Lessner, 2016 |

| Type species | |

| †Vivaron haydeni Lessner et al, 2016

| |

Vivaron is a genus of rauisuchid known from the Late Triassic (middle Norian) Chinle Formation in New Mexico. It is the second rauisuchid known from the southwestern United States, and it highlights the wide biogeographic range similar rauisuchid taxa occupied during the Late Triassic across Pangaea, despite the varied faunal assemblages at different latitudes.[1]

Discovery

Vivaron was named in 2016 from material collected at the Hayden Quarry at Ghost Ranch, New Mexico in 2009.[2] The locality is part of the Chinle Formation in the Petrified Forest Member, and dates to the middle Norian ~212 Ma, possibly representing one of the youngest known rauisuchids. Prior to its description, all Late Triassic rauisuchid material from Texas, Arizona and New Mexico had been referred to Postosuchus kirkpatricki. However, the rauisuchid remains from Hayden Quarry could be clearly distinguished from Postosuchus, and was erected as a new taxon Vivaron haydeni.

The generic epithet was named for Vivaron, a mythical 30 foot rattlesnake spirit that was said to live under Mesa Huerfano (Orphan Mesa) at Ghost Ranch,[3] and the specific name in honour of John Hayden, a hiker who discovered the Hayden Quarry in 2002 where the material for Vivaron was collected.[1]

Description

Vivaron is known only from three jaw bones, associated skull fragments and referred hip bones. Comparisons with related taxa allow for an estimated length of between 12 to 18 feet (3.7 to 5.5 m), similar in size and appearance to other rauisuchids.[2]

Vivaron can be distinguished from other rauisuchids by the presence of two prongs on the posterior portion of the maxilla where it articulates with the jugal. It is also unique among rauisuchids by possessing five alveoli in the premaxilla, similar to the state in early crocodylomorphs but in contrast with other rauisuchids, which only have four alveoli (however, a reconstruction of a Postosuchus skull (UCMP A269) figured in Long & Murry 1995[4] (Fig. 121) possibly shows a fifth alveolus in the left premaxilla). Vivaron was noted to share a number of characteristics with Teratosaurus, to which it is believed to be closely related to, particularly features of the maxilla and antorbital fossa. The referred hip elements also share similarities to the referred hips of Teratosaurus, potentially supporting their referral to each taxon, despite neither being directly associated with the holotype.[1]

Classification

Vivaron was found to be a member of Rauisuchidae by Lessner et al. 2016 in their phylogenetic analysis, with no changes to the relationships of pseudosuchians found in a previous analysis (Nesbitt, 2011).[5] The analysis recovered Rauisuchidae as monophyletic but completely unresolved, with all six species in a polytomy. Surveys of the interrelationships within Rauisuchidae found P. kirkpatricki as the sister taxon of Polonosuchus, and Rauisuchus as the sister taxon to the rest of Rauisuchidae.

The presence of Vivaron in the southwestern United States in addition to Postosuchus has implications for the classification of numerous other rauisuchid material from these locations, as almost all of it had been referred to the single species Postosuchus kirkpatricki based on their geographic location. Vivaron demonstrates the need for more detailed morphological analysis of all rauisuchid remains in the southwestern United States when determining their assignment within the group, and not refer them to a taxon based only on geographic distribution.

The inferred close relationship between Vivaron and Teratosaurus also has implications for the biogeography of middle Norian Pangaea. During the late Carnian to early Norian, very similar faunal associations were present across Pangaea, all of which included rauisuchid taxa. However, by the middle Norian faunal assemblages were becoming disparate, particularly evident between high-latitude locations in Europe (including sauropodomorphs, phytosaurs, aetosaurs and turtles) and the lower-latitude southern United States (including dinosauromorphs, metoposaurs, phytosaurs, aetosaurs and non-archosaur archosauromorphs). The close relationship between Vivaron and Teratosaurus demonstrates that despite being widely geographically separated and belonging to distinct faunal assemblages, there was a clear biogeographic link between the Chinle Formation and high-latitude Pangaea, and that rauisuchids were able to maintain a widespread distribution into the middle Norian.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d Emily J. Lessner; Michelle R. Stocker; Nathan D. Smith; Alan H. Turner; Randall B. Irmis; Sterling J. Nesbitt (2016). "A new rauisuchid (Archosauria, Pseudosuchia) from the Upper Triassic (Norian) of New Mexico increases the diversity and temporal range of the clade". PeerJ. 4: e2336. doi:10.7717/peerj.2336. PMC 5018681. PMID 27651983.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Mackay, Steven (6 September 2016). "Undergraduate researcher leads study naming a new species of reptile from 212 million years ago". Virginia Tech News. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Poling-Kempes, Lesley (2005). Ghost Ranch. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2005. p. 14. ISBN 0816523479.

- ^ Robert A. Long; Philip A. Murry (1995). "Late Triassic (Carnian and Norian) Tetrapods from the Southwestern United States". Bulletin of the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. 4: 121.

- ^ Nesbitt, Sterling J. (2011). "The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origin of Major Clades". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292. doi:10.1206/352.1. hdl:2246/6112. S2CID 83493714.