George Frideric Handel: Difference between revisions

→External links: Added a link to a biographical web site. |

|||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

[[File:Portrait of George Frederick Handel engraved by Charles Turner 1821 (mezzotint) - Handel Collection, Foundling Museum, London.JPG|right|thumb|Portrait of George Frederick Handel engraved by Charles Turner, 1821]] |

[[File:Portrait of George Frederick Handel engraved by Charles Turner 1821 (mezzotint) - Handel Collection, Foundling Museum, London.JPG|right|thumb|Portrait of George Frederick Handel engraved by Charles Turner, 1821]] |

||

In 1710, Handel became ''[[Kapellmeister]]'' to George, [[Prince-elector|Elector]] of [[Hanover]], who would become King [[George I of Great Britain]] in 1714.<ref name="Burrows"/>{{Rp|[38]}} He visited [[Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici]] and her husband on his way to London in 1710. With his opera ''[[Rinaldo (opera)|Rinaldo]]'' Handel had much success |

In 1710, Handel became ''[[Kapellmeister]]'' to George, [[Prince-elector|Elector]] of [[Hanover]], who would become King [[George I of Great Britain]] in 1714.<ref name="Burrows"/>{{Rp|[38]}} He visited [[Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici]] and her husband on his way to London in 1710. With his magic opera ''[[Rinaldo (opera)|Rinaldo]]'', based on [[Torquato Tasso]]'s ''[[Jerusalem Delivered|La Gerusalemme Liberata]]'' Handel had much success. He decided to settle permanently in 1712, receiving a yearly income of £200 from [[Anne of Great Britain|Queen Anne]]. One of his most important patrons was the young and wealthy [[Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington]], who showed an early love of his music.<ref>Handel. A Celebration of his Life and Times 1685–1759. National Portrait Gallery, p. 92.</ref> For him he wrote [[Amadigi di Gaula]], a fascinating opera, featuring [[Nicolo Grimaldi]], and no voices lower than [[alto]]. In July of 1717 Handel's ''[[Water Music (Handel)|Water Music]]'' was more than three times performed on the Thames for the King and his guests, like Anne Vaughan, the [[Charles Powlett, 3rd Duke of Bolton|Dutches of Bolton]] and [[Harriet Pelham-Holles, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne]], [[Henrietta Godolphin|Countess Godolphin]], [[Sophia von Kielmansegg, Countess of Darlington]], [[Lord George Hamilton]], the first [[Earl of Orkney]]. The [[barge]]s, heading for [[Chelsea]] and [[Lambeth]] and leaving the party after midnight, were using the [[tide]]s on the river. The composition was succesfull as a reconciliation between the king and Handel.<ref name="Burrows"/>{{Rp|[77]}} |

||

Handel spent the most carefree time of his life at [[Cannons (house)|Cannons]] and laid the cornerstone for his future choral compositions in the twelve ''[[James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos|Chandos]] Anthems''.<ref>Bukofzer, M. (1983) Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, p. 333-35</ref> [[Romain Rolland]] stated that these [[anthem]]s were as important for his oratorios as the cantatas were for his operas. Rolland also highly estimated ''[[Acis and Galatea (Handel)|Acis and Galatea]]'', like Winton Dean, who wrote that "the music catches breath and disturbs the memory".<ref>Dean, W. Handel's Operas 1704-1726, p. 209.</ref> During Handel's lifetime it was his most performed work. |

Handel spent the most carefree time of his life at [[Cannons (house)|Cannons]] and laid the cornerstone for his future choral compositions in the twelve ''[[James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos|Chandos]] Anthems''.<ref>Bukofzer, M. (1983) Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, p. 333-35</ref> [[Romain Rolland]] stated that these [[anthem]]s were as important for his oratorios as the cantatas were for his operas. Rolland also highly estimated ''[[Acis and Galatea (Handel)|Acis and Galatea]]'', like Winton Dean, who wrote that "the music catches breath and disturbs the memory".<ref>Dean, W. Handel's Operas 1704-1726, p. 209.</ref> During Handel's lifetime it was his most performed work. |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

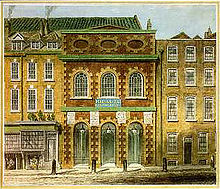

[[File:London Handel House.jpg|thumb|left|Handel House at 25 [[Brook Street]], London.]] |

[[File:London Handel House.jpg|thumb|left|Handel House at 25 [[Brook Street]], London.]] |

||

===Royal Academy of Music (1719)=== |

|||

In 1719 Handel traveled to [[Dresden]] to attend the newly built opera. He saw ''Teofane'' by [[Antonio Lotti]], composed for the wedding of [[August III of Poland]] and engaged the cast for as long as possible on account of the [[Royal Academy of Music (1719)]]. The next year |

In 1719 Handel traveled to [[Dresden]] to attend the newly built opera. He saw ''Teofane'' by [[Antonio Lotti]], composed for the wedding of [[August III of Poland]] and engaged the cast for as long as possible on account of the [[Royal Academy of Music (1719)|Royal Academy of Music]]. The next year [[Senesino]], [[Margherita Durastanti]] and [[Giuseppe Maria Boschi]] arrived in London. For the [[castrato]] Senesino, in the role of [[Radamisto (Handel)|Radamisto]] Handel wrote one of his favourite arias, ''Cara sposa''. Senesino who would stay sixteen years in London. |

||

Handel used the libretto of ''Teofane'' for his [[Ottone]], first performed in 1723. In that same Handel moved into a [[Georgian architecture|Georgian]] house at 25 [[Brook Street]], London, which he rented for the rest of his life.<ref name="Burrows"/>{{Rp|[387]}} This house in [[Mayfair]] is now the [[Handel House Museum]].<ref>In 2000, the upper stories of 25 Brook Street were leased to the Handel House Trust, and after an extensive restoration program, the Handel House Museum, opened to the public with an events programme of baroque music.</ref> In 1724 and 1725 Handel wrote several outstanding and successfull opera's, [[Giulio Cesare]], [[Tamerlano]] and [[Rodelinda]] with many [[da capo]] arias that made him so famous. He stopped writing cantantas, after composing ''Silete venti''. In 1726 ''[[Scipio (opera)|Scipio]]'', starring [[Francesca Cuzzoni]], was performed as a stopgap, (from which remains the regimental slow march of the British [[Grenadier Guards]]).<ref name="Deutsch"/>{{Rp|[194]}} For [[Siroe]] Handel used a libretto from [[Pietro Metastasio]]. In [[Alessandro]] and [[Admeto]] the [[prima donna]] [[Faustina Bordoni]] appeared together with her rival Cuzzoni. |

|||

In 1727 Handel was commissioned to write four anthems for the coronation ceremony of [[George II of Great Britain|King George II]]. One of these, ''[[Zadok the Priest]]'', has been played at every [[Coronation of the British monarch|British coronation ceremony]] since. In 1728 [[the Beggar's Opera]] premiered at [[Lisle's Tennis Court|Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre]] and ran for 62 consecutive performances, which was the longest run in theatre history up to that time. Handel went broke and started a new company |

In 1727 Handel was commissioned to write four anthems for the coronation ceremony of [[George II of Great Britain|King George II]]. One of these, ''[[Zadok the Priest]]'', has been played at every [[Coronation of the British monarch|British coronation ceremony]] since. Because of the death of [[George I of England|George I]] and Handel becoming a citizin [[Riccardo Primo]] was rewritten. In 1728 [[the Beggar's Opera]] premiered at [[Lisle's Tennis Court|Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre]] and ran for 62 consecutive performances, which was the longest run in theatre history up to that time. Handel went broke and started a new company. |

||

Handel became the partner of [[John James Heidegger]] in the management of the [[Her Majesty's Theatre|King's Theatre]], but first Handel traveled to Italy to engage seven new singers. On his way back he visited his mother and probably met with [[Wilhelm Friedemann Bach]], sent by his father, as the story goes. [[Johann Sebastian Bach]] working in [[Cöthen]], only 20 miles away arrived too late to meet with his famous collegue who had left earlier that day.<ref>[[Johann Nikolaus Forkel]] (1802) Über Johann Sebastian Bach Leben, Kunst und Kunstwerke, p. 63 (reprint 1950); .</ref> Back in London Handel produced two English oratoria [[Esther (Handel)|Esther]] and [[Deborah (Handel)|Deborah]], both commercially successful and he was able to invest in the [[South Sea Company]]. In the long run Handel failed to compete with the [[Opera of the Nobility]], engaging musicians as [[Johann Adolf Hasse]], [[Nicolo Porpora]] and the famous castrato [[Farinelli]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | During March of 1734 Handel directed ''This is the day which the Lord hath made'' a wedding [[anthem]], and a [[pasticcio]] [[Parnasso in Festa]] for the [[Princess of Orange]].<ref name=Dent/>{{Rp|[33]}} Handel started his third company at [[Covent Garden Theatre]], where [[Ariodante]], [[ |

||

| ⚫ | During March of 1734 Handel directed ''This is the day which the Lord hath made'' a wedding [[anthem]], and a [[pasticcio]] [[Parnasso in Festa]] for the [[Princess of Orange]].<ref name=Dent/>{{Rp|[33]}} Handel started his third company at [[Covent Garden Theatre]], where [[Ariodante]], and [[Alcina]] were premiered and ''[[Alexander's Feast (Handel)|Alexander’s Feast]] or the Power of Music'' based on [[John Dryden]]'s ''[[Alexander's Feast (Dryden)|Alexander's Feast]]'', starring [[Anna Maria Strada del Pò]] and [[John Beard (tenor)]]. |

||

| ⚫ | In April 1737, at age 52, Handel suffered a stroke |

||

| ⚫ | In April 1737, at age 52, Handel suffered a [[stroke]] which left his right arm temporarily paralysed—preventing him from performing.<ref name="Burrows"/>{{Rp|[395]}} He also complained of difficulties in focusing his sight. Nobody expected Handel would ever be able to perform again. To aid recovery, Handel travelled in 1740 to [[Aachen]], [[Germany]] — taking hot baths and eventually playing the organ for the local audience.<ref>For new insights on this episode, see Ilias Chrissochoidis: "Handel Recovering: Fresh Light on his Affairs in 1737," ''Eighteenth-Century Music'' 5/2 (2008): 237-44.</ref> Having lost a fortune in operatic management, Handel gave up the business in 1741. His last [[baroque opera]] [[Deidamia (opera)|Deidamia]] was performed only three times. It was the end of the line: in the meantime he had more and more success with his English oratoria. |

||

Having lost a fortune in operatic management, Handel gave up the business in 1740. |

|||

==Later years== |

==Later years== |

||

Revision as of 11:13, 27 December 2009

George Frideric Handel (German: Georg Friedrich Händel; pronounced [ˈhɛndəl]) (23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German–English Baroque composer, who is famous for his operas, oratorios, and concerti grossi. He was born in Germany, trained in Italy, and spent most of his life in England. Born in Halle in the Duchy of Magdeburg, he settled in England in 1712, becoming a naturalised subject of the British crown on 20 February 1727.[1] His works include Messiah, Water Music, and Music for the Royal Fireworks. Strongly influenced by the techniques of the great composers of the Italian Baroque era, as well as the English composer Henry Purcell, Handel's music became well-known to many composers, including Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven.

Early years

Handel was born in Halle, Saxony-Anhalt in the Duchy of Magdeburg (a province of Brandenburg-Prussia) to Georg and Dorothea (née Taust) Händel in 1685,[2]: [1] the same year that both Johann Sebastian Bach and Domenico Scarlatti were born. Handel displayed considerable musical talent at an early age; by the age of seven he was a skillful performer on the harpsichord and pipe organ.[3]: [3–4] However, his father, a distinguished citizen of Halle and an eminent barber-surgeon who served as valet and barber to the courts of the Duchy of Saxe-Weissenfels and the Margraviate of Brandenburg,[4] was opposed to his son's wish to pursue a musical career, preferring him to study law. By contrast, Handel's mother, Dorothea, encouraged his musical aspirations.

Nevertheless, the young Handel was permitted to take lessons in musical composition and keyboard technique from Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, the organist of the Liebfrauenkirche, Halle. Handel learned about harmony and contemporary styles. He studied with Zachow from 1692 to 1703, when he left for Hamburg. He analyzed scores and learned to work fugue subjects and copy music. Sometimes he would take his teacher's place as organist for services.[5]: [17] For his seventh birthday his aunt, Anna, gave him a spinet, which was placed in the attic for Handel to play, whenever he could avoid his father.[6][7]

From Halle to Italy

Handel's progress was interrupted in 1697 when his father died. In 1702, following his father's wishes, Handel began the study of law at the University of Halle;[5]: [17–18] however, he abandoned law for music, becoming the organist at the Protestant Cathedral. In 1703, he moved to Hamburg, accepting a position as violinist and harpsichordist in the orchestra of the opera house.[8]: [18] There, he met Johann Mattheson, Christoph Graupner and Reinhard Keiser. His first two operas, Almira and Nero, were produced in 1705.[8]: [19] He produced two other early operas, Daphne and Florindo, in 1708.

During 1706, Handel travelled to Italy at the invitation of Gian Gastone de' Medici, whom he had met in 1703/1704.[9] Handel also met Medici's brother Ferdinando, who had succeeded in making Florence the musical capital of Italy, attracting the leading talents of his day. There Handel met the librettist Antonio Salvi, with whom he would cooperate. The rumour went Handel had a love affair with Vittoria Tarquini, a singer. Handel left for Rome and while opera was (temporarily) banned in the Papal States Handel composed sacred music; the famous Dixit Dominus (1707) is from this era.: [24, 26] Besides he wrote many cantatas in pastoral style for musical gatherings in the palace of Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, Benedetto Pamphili and Carlo Colonna. Two oratorios, La Resurrezione and Il Trionfo del Tempo, were produced in a private setting for Ruspoli and Ottoboni in 1709 and 1710, respectively. Rodrigo, his first immature, but all-Italian opera, was produced in the Cocomero theatre in Florence in 1707.[8]: [29-30] Agrippina was first produced at San Giovanni Grisostomo for cardinal Vincenzo Grimani in 1709 and ran for an unprecedented 27 performances in the prettiest theatre at Venice. It showed remarkable maturity and established his reputation as an opera composer. The audience were thunderstruck with the grandeur and sublimity of his style.[10]

The move to London

In 1710, Handel became Kapellmeister to George, Elector of Hanover, who would become King George I of Great Britain in 1714.[8]: [38] He visited Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici and her husband on his way to London in 1710. With his magic opera Rinaldo, based on Torquato Tasso's La Gerusalemme Liberata Handel had much success. He decided to settle permanently in 1712, receiving a yearly income of £200 from Queen Anne. One of his most important patrons was the young and wealthy Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, who showed an early love of his music.[11] For him he wrote Amadigi di Gaula, a fascinating opera, featuring Nicolo Grimaldi, and no voices lower than alto. In July of 1717 Handel's Water Music was more than three times performed on the Thames for the King and his guests, like Anne Vaughan, the Dutches of Bolton and Harriet Pelham-Holles, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Countess Godolphin, Sophia von Kielmansegg, Countess of Darlington, Lord George Hamilton, the first Earl of Orkney. The barges, heading for Chelsea and Lambeth and leaving the party after midnight, were using the tides on the river. The composition was succesfull as a reconciliation between the king and Handel.[8]: [77]

Handel spent the most carefree time of his life at Cannons and laid the cornerstone for his future choral compositions in the twelve Chandos Anthems.[12] Romain Rolland stated that these anthems were as important for his oratorios as the cantatas were for his operas. Rolland also highly estimated Acis and Galatea, like Winton Dean, who wrote that "the music catches breath and disturbs the memory".[13] During Handel's lifetime it was his most performed work.

Royal Academy of Music (1719)

In 1719 Handel traveled to Dresden to attend the newly built opera. He saw Teofane by Antonio Lotti, composed for the wedding of August III of Poland and engaged the cast for as long as possible on account of the Royal Academy of Music. The next year Senesino, Margherita Durastanti and Giuseppe Maria Boschi arrived in London. For the castrato Senesino, in the role of Radamisto Handel wrote one of his favourite arias, Cara sposa. Senesino who would stay sixteen years in London.

Handel used the libretto of Teofane for his Ottone, first performed in 1723. In that same Handel moved into a Georgian house at 25 Brook Street, London, which he rented for the rest of his life.[8]: [387] This house in Mayfair is now the Handel House Museum.[14] In 1724 and 1725 Handel wrote several outstanding and successfull opera's, Giulio Cesare, Tamerlano and Rodelinda with many da capo arias that made him so famous. He stopped writing cantantas, after composing Silete venti. In 1726 Scipio, starring Francesca Cuzzoni, was performed as a stopgap, (from which remains the regimental slow march of the British Grenadier Guards).[2]: [194] For Siroe Handel used a libretto from Pietro Metastasio. In Alessandro and Admeto the prima donna Faustina Bordoni appeared together with her rival Cuzzoni.

In 1727 Handel was commissioned to write four anthems for the coronation ceremony of King George II. One of these, Zadok the Priest, has been played at every British coronation ceremony since. Because of the death of George I and Handel becoming a citizin Riccardo Primo was rewritten. In 1728 the Beggar's Opera premiered at Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre and ran for 62 consecutive performances, which was the longest run in theatre history up to that time. Handel went broke and started a new company.

Handel became the partner of John James Heidegger in the management of the King's Theatre, but first Handel traveled to Italy to engage seven new singers. On his way back he visited his mother and probably met with Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, sent by his father, as the story goes. Johann Sebastian Bach working in Cöthen, only 20 miles away arrived too late to meet with his famous collegue who had left earlier that day.[15] Back in London Handel produced two English oratoria Esther and Deborah, both commercially successful and he was able to invest in the South Sea Company. In the long run Handel failed to compete with the Opera of the Nobility, engaging musicians as Johann Adolf Hasse, Nicolo Porpora and the famous castrato Farinelli.

During March of 1734 Handel directed This is the day which the Lord hath made a wedding anthem, and a pasticcio Parnasso in Festa for the Princess of Orange.[3]: [33] Handel started his third company at Covent Garden Theatre, where Ariodante, and Alcina were premiered and Alexander’s Feast or the Power of Music based on John Dryden's Alexander's Feast, starring Anna Maria Strada del Pò and John Beard (tenor).

In April 1737, at age 52, Handel suffered a stroke which left his right arm temporarily paralysed—preventing him from performing.[8]: [395] He also complained of difficulties in focusing his sight. Nobody expected Handel would ever be able to perform again. To aid recovery, Handel travelled in 1740 to Aachen, Germany — taking hot baths and eventually playing the organ for the local audience.[16] Having lost a fortune in operatic management, Handel gave up the business in 1741. His last baroque opera Deidamia was performed only three times. It was the end of the line: in the meantime he had more and more success with his English oratoria.

Later years

Following his recovery, Handel focused on composing oratorios instead of opera. Handel's Messiah was first performed in New Musick Hall in Fishamble Street, Dublin on 13 April 1742, with twenty-six boys and five men from the combined choirs of St Patrick's and Christ Church cathedrals participating.[17]: [48]

In 1749 he composed Music for the Royal Fireworks; 12,000 people came to listen.[8]: [297–98] Three people died, including one of the trumpeters, on the day after.

In 1750 Handel arranged a performance of Messiah to benefit the Foundling Hospital. The performance was considered a great success and was followed by annual concerts that continued throughout his life. In recognition of his patronage, Handel was made a governor of the Hospital the day after his initial concert. He bequeathed a fair copy of Messiah to the institution upon his death.[17]: [56] His involvement with the Foundling Hospital is today commemorated with a permanent exhibition in London's Foundling Museum, which also holds the Gerald Coke Handel Collection. In addition to the Foundling Hospital, Handel also gave to a charity that helped to assist impoverished musicians and their families. Also, during the summer of 1741, the Duke of Devonshire invited Handel to Dublin to give concerts for the benefit of local hospitals.[3]: [40, 41]

In August 1750, on a journey back from Germany to London, Handel was seriously injured in a carriage accident between The Hague and Haarlem in the Netherlands.[3]: [63] In 1751 his eyesight started to fail in one eye. The cause was a cataract which was operated on by the great charlatan Chevalier Taylor. This lead to uveitis and subsequent loss of vision. Jephtha was first performed on 26 February 1752; even though it was his last oratorio, it was no less a masterpiece than his earlier works.[8]: [354-55] He died some eight years later, in 1759, in London, at the age of 74, with his last attended performance being his own Messiah. More than three thousand mourners attended his funeral, which was given full state honours, and he was buried in Westminster Abbey.[17]: [60]

Handel never married, and kept his personal life private. He left a sizable estate at his death—worth £20,000, the bulk of which he bequeathed to a niece in Germany—as well as gifts to his other relations, servants, friends and favourite charities.

Works

- Main articles: List of compositions by George Frideric Handel and List of operas by Handel.

Handel's compositions include 42 operas; 29 oratorios; more than 120 cantatas, trios and duets; numerous arias; chamber music; a large number of ecumenical pieces; odes and serenatas; and 16 organ concerti. His most famous work, the Messiah oratorio with its "Hallelujah" chorus, is among the most popular works in choral music and has become a centerpiece of the Christmas season. Also popular are the Opus 3 and 6 Concerti Grossi, as well as "The Cuckoo and the Nightingale", in which birds are heard calling during passages played in different keys representing the vocal ranges of two birds. Also notable are his sixteen keyboard suites, especially The Harmonious Blacksmith.

Handel introduced various previously uncommon musical instruments in his works: the viola d'amore and violetta marina (Orlando), the lute (Ode for St. Cecilia's Day), three trombones (Saul), clarinets or small high cornets (Tamerlano), theorbo, French horn (Water Music), lyrichord, double bassoon, viola da gamba, bell chimes, positive organ, and harp (Giulio Cesare, Alexander's Feast).[18]

Handel's works have been catalogued and are commonly referred to by a HWV number. For example, Handel's Messiah is also known as HWV 56.

Legacy

After his death, Handel's Italian operas fell into obscurity, save for selections such as the ubiquitous aria from Serse, "Ombra mai fù". His reputation throughout the 19th century and first half of the 20th century, particularly in the Anglophone countries, rested primarily on his English oratorios, which were customarily performed by enormous choruses of amateur singers on solemn occasions. These include Esther (1718); Athalia (1733); Saul (1739); Israel in Egypt (1739); Messiah (1742); Samson (1743); Judas Maccabaeus (1747); Solomon (1748); and Jephtha (1752). His best are based on a libretto by Charles Jennens.

Since the 1960s, with the revival of interest in baroque music, original instrument playing styles, and the prevalence of countertenors who could more accurately replicate castrato roles, interest has revived in Handel's Italian operas, and many have been recorded and performed onstage. Of the fifty he wrote between 1705 and 1738, Agrippina (1709), Rinaldo (1711, 1731), Orlando (1733), Ariodante (1735), Alcina (1735) and Serse (1738, also known as Xerxes) stand out and are now performed regularly in opera houses and concert halls. Arguably the finest, however, are Giulio Cesare (1724), Tamerlano (1724) and Rodelinda (1725), which, thanks to their superb orchestral and vocal writing, have entered the mainstream opera repertoire.

Also revived in recent years are a number of secular cantatas and what one might call secular oratorios or concert operas. Of the former, Ode for St. Cecilia's Day (1739) (set to texts of John Dryden) and Ode for the Birthday of Queen Anne (1713) are particularly noteworthy. For his secular oratorios, Handel turned to classical mythology for subjects, producing such works as Acis and Galatea (1719), Hercules (1745), and Semele (1744). In terms of musical style, particularly in the vocal writing for the English-language texts, these works have close kinship with the above-mentioned sacred oratorios, but they also share something of the lyrical and dramatic qualities of Handel's Italian operas. As such, they are sometimes performed onstage by small chamber ensembles. With the rediscovery of his theatrical works, Handel, in addition to his renown as instrumentalist, orchestral writer, and melodist, is now perceived as being one of opera's great musical dramatists.

Handel has generally been accorded high esteem by fellow composers, both in his own time and since.[19] Bach even attempted, unsuccessfully, to meet with Handel while he was visiting Halle.[3]: [23] Mozart is reputed to have said of him, "Handel understands effect better than any of us. When he chooses, he strikes like a thunder bolt."[20] and to Beethoven he was "the master of us all... the greatest composer that ever lived. I would uncover my head and kneel before his tomb."[20] The latter emphasized above all the simplicity and popular appeal of Handel's music when he said, "Go to him to learn how to achieve great effects, by such simple means."

After Handel’s death, many composers wrote works based on or inspired by his music. The first movement from Louis Spohr’s Symphony No. 6, Op. 116, "The Age of Bach and Handel", resembles two melodies from Handel's Messiah. In 1797 Ludwig van Beethoven published the 12 Variations in G major on ‘See the conqu’ring hero comes’ from Judas Maccabaeus by Handel, for cello and piano. Guitar virtuoso Mauro Giuliani composed his Variations on a Theme by Handel, Op. 107 for guitar, based on Handel's Suite No. 5 in E major, HWV 430, for harpsichord. In 1861, using a theme from the second of Handel's harpsichord suites, Johannes Brahms wrote the Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel, Op. 24, one of his most successful works (it even received praise from Richard Wagner). Several works by the French composer Félix-Alexandre Guilmant use themes by Handel, for example his March on a Theme by Handel for organ, which uses a theme from the Messiah. French composer and flautist Philippe Gaubert wrote his Petite marche for flute and piano based on the fourth movement of Handel’s Trio Sonata, Op. 5, No. 2, HWV 397. Argentine composer Luis Gianneo composed his Variations on a Theme by Handel for piano. In 1911, Australian born composer and pianist Percy Grainger based one of his most famous works on the final movement of Handel's Suite No. 5 in E major (just like Giuliani). He first wrote some variations on the theme, which he titled Variations on Handel’s ‘The Harmonious Blacksmith’ . Then he used the first sixteen bars of his set of variations to create Handel in the Strand, one of his most beloved pieces, of which he made several versions (for example, the piano solo version from 1930). Arnold Schoenberg’s Concerto for String Quartet and Orchestra in B flat major (1933) was composed after Handel's Concerto Grosso, Op. 6/7.

He is commemorated as a musician in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church on July 28, with Johann Sebastian Bach and Heinrich Schütz.

Handel's works were edited by Samuel Arnold (40 vols., London, 1787–1797), and by Friedrich Chrysander, for the German Händel-Gesellschaft (100 vols., Leipzig, 1858–1902).

Handel adopted the spelling "George Frideric Handel" on his naturalization as a British subject, and this spelling is generally used in English-speaking countries. The original form of his name (Georg Friedrich Händel) is generally used in Germany and elsewhere, but he is known as "Haendel" in France, which causes no small amount of grief to cataloguers everywhere. Another composer with a similar name, Handl, was a Slovene and is more commonly known as Jacobus Gallus.

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

Scores and recordings

- Free scores by George Frideric Handel at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP): includes Complete Works Edition (Ausgabe der Deutschen Händelgesellschaft)

- Free scores by George Frideric Handel in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- The Mutopia Project provides free downloading of sheet music and MIDI files for some of Handel's works.

- Free typeset sheet music of Handel's works from Cantorion.org

- Template:IckingArchive

- Handel cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- Kunst der Fuge: George Frideric Handel - MIDI files

- Water Music, Organ Concertos op. 4, Tamerlano, etc. Creative Commons recordings

See also

- Handel Commemoration

- John Baptist Grano

- List of compositions by George Frideric Handel

- List of operas by Handel

Primary sources

Further reading

- Dean, W. (2006) “Handel’s Operas, 1726-1741” (The Boydell Press)

Notes

- ^ British Citizen by Act of Parliament: George Frideric Handel

- ^ a b Otto Erich Deutsch. Handel A Documentary Biography. London: Adams and Charles Black Limited, 1955,

- ^ a b c d e Dent, Edward Joseph. Handel. R A Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1-4191-2275-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Adams Aileen, K., Hofestadt, B., "Georg Handel (1622–97): the barber-surgeon father of George Frideric Handel (1685–1759)", Journal of Medical Biography, 2005, Aug; 13(3):142–49.

- ^ a b Jonathan Keates.Handel, the man and his music. New York: St Martin's Press, 1985

- ^ Deutsch, Otto Erich, "Handel: A Documentary Biography", Music & Letters, 36(3) (July 1955), pp. 269–72.

- ^ Hird, Edward, Rev., Rediscovering Handel's Messiah, April 1993, Deep Cove Crier, North Vancouver, B.C., Canada.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Donald Burrows. Handel. Oxford University Press, 1994.

- ^ Handel as Orpheus: voice and desire in the chamber cantatas by Ellen T. Harris [1]

- ^ Dean, W. & J.M. Knapp (1987) Handel's Operas, p. 129.

- ^ Handel. A Celebration of his Life and Times 1685–1759. National Portrait Gallery, p. 92.

- ^ Bukofzer, M. (1983) Music in the Baroque Era. From Monteverdi to Bach, p. 333-35

- ^ Dean, W. Handel's Operas 1704-1726, p. 209.

- ^ In 2000, the upper stories of 25 Brook Street were leased to the Handel House Trust, and after an extensive restoration program, the Handel House Museum, opened to the public with an events programme of baroque music.

- ^ Johann Nikolaus Forkel (1802) Über Johann Sebastian Bach Leben, Kunst und Kunstwerke, p. 63 (reprint 1950); .

- ^ For new insights on this episode, see Ilias Chrissochoidis: "Handel Recovering: Fresh Light on his Affairs in 1737," Eighteenth-Century Music 5/2 (2008): 237-44.

- ^ a b c Percy M Young Handel. New York: David White Company, 1966.

- ^ Textbook in CD Sacred Arias with Harp & Harp Duets by Rachel Ann Morgan & Edward Witsenburg.

- ^ BBC Press Release

- ^ a b Young, Percy Marshall (1975-04-01) [1947]. Handel (Master Musician series). J.M.Dent & Sons. p. 254. ISBN 0-4600-3161-9.

References

- Burrows, Donald. Handel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-19-816470-X

- Chrissochoidis, Ilias. "Early Reception of Handel's Oratorios, 1732-1784: Narrative – Studies – Documents" (Ph.D. dissertation, Stanford University, 2004), available through UMI.

- Deutsch, Otto Erich, Handel: A Documentary Biography, 1955.

- Frosch, W.A., The "case" of George Frideric Handel, New England Journal of Medicine, 1989; 321:765-769, Sep 14, 1989. [2]

- Harris, Ellen T. (general editor) The librettos of Handel's operas: a collection of seventy librettos documenting Handel's operatic career New York: Garland, 1989. ISBN 0-8240-3862-2

- Harris, Ellen T. Handel as Orpheus. Voice and Desire in the Chamber Cantatas Harvard University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-674-00617-8

- Hogwood, Christopher. Handel. London: Thames and Hudson, 1984. ISBN 0-500-01355-1

- Keates, Jonathan. Handel, the man and his music. London: V. Gollancz, 1985. ISBN 0-575-03573-0

- Dean, Winton and John Merrill Knapp. Handel's Operas, 1704-1726 (Volume 1) Oxford: Clarendon Press. (1987; 2nd Ed. 1994 (softcover) ISBN 0-198-16441-6

- Meynell, Hugo. The Art of Handel's Operas The Edwin Mellen Press (1986) ISBN 0-889-46425-1

External links

- Edward Dent's Handel biography from Project Gutenberg

- The second volume of Winton Dean for "Handel's Operas" covering the years 1726-1741

- Friedrich Chrysander's Handel biography (in German)

- Biographical details web site

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- 1685 births

- 1759 deaths

- People from Halle, Saxony-Anhalt

- George Frideric Handel

- Baroque composers

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- Composers for pipe organ

- English classical organists

- English composers

- English people of German descent

- German classical organists

- German composers

- Members of the Royal Society of Musicians

- Opera composers

- Glee composers

- Organ improvisers

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- People from Hanover

- People from the Duchy of Magdeburg

- Walhalla enshrinees

- German immigrants to the United Kingdom

- 18th-century German people