Particle: Difference between revisions

IvoryMeerkat (talk | contribs) →Composition: some tags... not sure if much of this is true. |

revert, it's sourced and completely mainstream (http://perc.ufl.edu/particle.asp amongst others) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

==Size== |

==Size== |

||

[[File:NGC 4414 (NASA-med).jpg|150px|thumb|left|Galaxies are so large that stars can be considered particles next to them]] |

|||

The term "particle" is usually applied differently to three class of sizes. |

The term "particle" is usually applied differently to three class of sizes. The term ''[[macroscopic scale|macroscopic particle]]'', usually refers to particles much larger than [[atom]]s and [[molecule]]s. These are usually abstracted as [[point particle|point-like particles]], even though they have volumes, shapes, structures, etc. Examples of macroscopic particles would include [[dust]], [[sand]], pieces of [[debris]] during a [[car accident]], or even objects as big as the [[star]]s of a [[galaxy]].<ref> |

||

{{cite journal |

|||

|author=G. Stinson ''et al.'' |

|||

|date=2006 |

|||

|title=Star Formation and Feedback in Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamic Simulations—I. Isolated Galaxies |

|||

|journal=[[Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society]] |

|||

|volume=373 |pages=1074 |

|||

|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11097.x |

|||

|id={{arxiv|astro-ph/0602350}} |

|||

}}</ref> Another type, ''[[microscopic scale|microscopic particles]]'' usually refers to particles of sizes ranging from [[atom]]s to [[molecule]]s, such as [[carbon dioxide]], [[nanoparticle]]s, and [[colloid|colloidal particles]]. The smallest of particles are the ''[[subatomic particle]]s'', which refer to particles smaller than atoms.<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

{{cite web |

||

|title=Subatomic particle |

|title=Subatomic particle |

||

| Line 35: | Line 45: | ||

}}</ref> These would include particles such as the constituents of atoms – [[proton]]s, [[neutron]]s, and [[electron]] – as well as other types of particles which can only be produced in [[particle accelerator]]s or [[cosmic ray]]s. |

}}</ref> These would include particles such as the constituents of atoms – [[proton]]s, [[neutron]]s, and [[electron]] – as well as other types of particles which can only be produced in [[particle accelerator]]s or [[cosmic ray]]s. |

||

{{-}} |

{{-}} |

||

==Composition== |

==Composition== |

||

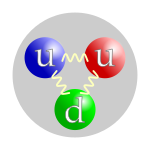

[[File:Quark structure proton.svg|150px|thumb|right|Proton are composed of three quarks, but quarks are not composed of other particles]] |

[[File:Quark structure proton.svg|150px|thumb|right|Proton are composed of three quarks, but quarks are not composed of other particles]] |

||

It is also useful |

It is also useful to classify particles according to composition. ''[[Composite particle]]s'' refer to particles that have [[wikt:composition|composition]] – that is particles which are made of other particles.<ref> |

||

{{cite web |

{{cite web |

||

|title=Composite particle |

|title=Composite particle |

||

| Line 50: | Line 59: | ||

|work=[[American Heritage Science Dictionary|YourDictionary.com]] |

|work=[[American Heritage Science Dictionary|YourDictionary.com]] |

||

|accessdate=2010-02-08 |

|accessdate=2010-02-08 |

||

}}</ref> According to our [[Standard Model|current understanding of the world]], only a very small number |

}}</ref> According to our [[Standard Model|current understanding of the world]], only a very small number of these exist, such as the [[lepton]]s, [[quark]]s or [[gluon]]s. However it is possible that some of these [[preon|might turn up to be composite particles after all]], and merely appear to be elementary for the moment.<ref> |

||

{{cite book |

{{cite book |

||

|author=I.A. D'Souza, C.S. Kalman |

|author=I.A. D'Souza, C.S. Kalman |

||

| Line 57: | Line 66: | ||

|publisher=[[World Scientific]] |

|publisher=[[World Scientific]] |

||

|isbn=981-02-1019-1 |

|isbn=981-02-1019-1 |

||

}}</ref> While composite particles can very often be considered [[point particle|''point-like'']], elementary particles are truly [[point particle|''punctual'']]. |

}}</ref> While composite particles can very often be considered [[point particle|''point-like'']], elementary particles are truly [[point particle|''punctual'']]. |

||

{{-}} |

{{-}} |

||

Revision as of 18:06, 24 February 2011

In the physical sciences, a particle is a small localized object to which can be ascribed several physical properties such as volume or mass.[1][2] The word is rather general in meaning, and is refined as needed by various scientific fields. Whether objects can be considered particles depends on the scale of the context; if geometrical properties such as size, shape, or structure are irrelevant, it can be considered a particle.[3] For example, grains of sand on a beach can be considered particles because the size of one grain of sand (~1 mm) is negligible compared to the beach, and the features of individual grains of sand are usually irrelevant to the problem at hand. However, grains of sand would not be considered particles if compared to buckyballs (~1 nm).

Size

The term "particle" is usually applied differently to three class of sizes. The term macroscopic particle, usually refers to particles much larger than atoms and molecules. These are usually abstracted as point-like particles, even though they have volumes, shapes, structures, etc. Examples of macroscopic particles would include dust, sand, pieces of debris during a car accident, or even objects as big as the stars of a galaxy.[4] Another type, microscopic particles usually refers to particles of sizes ranging from atoms to molecules, such as carbon dioxide, nanoparticles, and colloidal particles. The smallest of particles are the subatomic particles, which refer to particles smaller than atoms.[5] These would include particles such as the constituents of atoms – protons, neutrons, and electron – as well as other types of particles which can only be produced in particle accelerators or cosmic rays.

Composition

It is also useful to classify particles according to composition. Composite particles refer to particles that have composition – that is particles which are made of other particles.[6] For example, a carbon-14 atom is made of six protons, eight neutrons, and eight electrons. By contrast, elementary particles (also called fundamental particles) refer to particles that are not made of other particles.[7] According to our current understanding of the world, only a very small number of these exist, such as the leptons, quarks or gluons. However it is possible that some of these might turn up to be composite particles after all, and merely appear to be elementary for the moment.[8] While composite particles can very often be considered point-like, elementary particles are truly punctual.

See also

References

- ^ "Particle". AMS Glossary. American Meteorological Society.

- ^ "Particles". AMS Glossary. American Meteorological Society.

- ^ "Particle". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ^

G. Stinson; et al. (2006). "Star Formation and Feedback in Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamic Simulations—I. Isolated Galaxies". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 373: 1074. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11097.x. arXiv:astro-ph/0602350.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Subatomic particle". YourDictionary.com. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ^ "Composite particle". YourDictionary.com. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ^ "Elementary particle". YourDictionary.com. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ^ I.A. D'Souza, C.S. Kalman (1992). Preons: Models of Leptons, Quarks and Gauge Bosons as Composite Objects. World Scientific. ISBN 981-02-1019-1.

Further reading

- "What is a particle?". University of Florida, Particle Engineering Research Center. 23 July 2010.

- D.J. Griffiths (2008). Introduction to Particle Physics (2nd ed.). Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3527406018.