Fortress of Luxembourg

| Fortress of Luxembourg | |

|---|---|

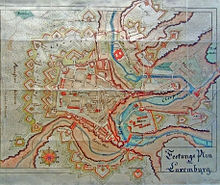

Fortress of Luxembourg, before its demolition in 1867 | |

The "Bock" promontory in 1867 | |

| Coordinates | 49°37′N 6°08′E / 49.61°N 6.13°E |

| Type | Fortress |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Mostly demolished |

| Site history | |

| Built | 15th–19th centuries |

| In use | Until 1867 |

| Demolished | 1867–1883 |

| Battles/wars | Siege of Luxembourg (1684), Siege of Luxembourg (1794–95) |

| Part of | City of Luxembourg: its Old Quarters and Fortifications |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 699 |

| Inscription | 1994 (18th Session) |

The Fortress of Luxembourg (Luxembourgish: Festung Lëtzebuerg; French: Forteresse de Luxembourg; German: Festung Luxemburg) is the former fortifications of Luxembourg City, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, which were mostly dismantled beginning in 1867. The fortress was of great strategic importance for the control of the Left Bank of the Rhine, the Low Countries, and the border area between France and Germany.

The fortifications were built gradually over nine centuries, from soon after the city's foundation in the tenth century until 1867. By the end of the Renaissance, Luxembourg was already one of Europe's strongest fortresses, but it was the period of great construction in the 17th and 18th centuries that gave it its fearsome reputation. Due to its strategic location, it became caught up in Europe-wide conflicts between the major powers such as the Habsburg–Valois wars, the War of the Reunions, and the French Revolutionary Wars, and underwent changes in ownership, sieges, and major alterations, as each new occupier—the Burgundians, French, Austrian and Spanish Habsburgs, and Prussians—made their own improvements and additions.

Luxembourg took pride in the flattering historical epithet of the "Gibraltar of the North" as a result of its alleged impregnability. By 1443 it had only been taken by surprise by Philip the Good. In 1795, the city, expecting imminent defeat and for fear of the following pillages and massacres, surrendered after a seven-month blockade and siege by the French, with most of its walls still unbreached. On this occasion, advocating to extend the revolutionary wars across the French borders, the French politician and engineer Lazare Carnot explained to the French House of Representatives, that in taking Luxembourg, France had deprived its enemies of "...the best fortress in Europe after Gibraltar, and the most dangerous for France", which had put any French movement across the border at a risk.[1][2] Thus, the surrender of Luxembourg made it possible for France to take control of the southern parts of the Low Countries and to annex them to her territory.

The city's great significance for the frontier between the Second French Empire and the German Confederation led to the 1866 Luxembourg Crisis, almost resulting in a war between France and Prussia over possession of the German Confederation's main western fortress. The 1867 Treaty of London required Luxembourg's fortress to be torn down and for Luxembourg to be placed in perpetual neutrality, signalling the end of the city's use as a military site. Since then, the remains of the fortifications have become a major tourist attraction for the city. In 1994, the fortress remains and the city's old quarter were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

History

[edit]From Roman fortification to medieval castle

[edit]In Roman times, two roads crossed on the plateau above the Alzette and Pétrusse rivers, one from Arlon to Trier, and another leading to Thionville. A circular wooden palisade was built around this crossing, which could provide protection to the farmers of the region in case of danger. Not far from this, on the Bock promontory, was the small Roman fortification Lucilinburhuc – this name later turned into Lützelburg, and later still into Luxembourg.[3][4]

After the Romans had left, the fortification fell into disrepair, until in 963 Count Siegfried of the House of Ardennes acquired the land in exchange for his territories in Feulen near Ettelbrück from St. Maximin's Abbey in Trier.[5] He built a small castle on the Bock promontory, which was connected to the plateau through a drawbridge.[5] In time, a settlement grew on the plateau. Knights and soldiers were billeted here on the rocky outcrop, while artisans and traders settled in the area beneath it, creating the long-standing social distinction between the upper and the lower city. The settlement had grown to a city by the 12th century, when it was protected by a city wall adjacent to the current Rue du Fossé. In the 14th century, a second city wall was built, which also incorporated the land of the Rham Plateau. A third wall later incorporated the urban area as far as today's Boulevard Royal.[6]

Development and use as fortress

[edit]The reinforcement of the fortifications which had begun in 1320 under John the Blind continued until the end of the 14th century. In 1443 Philip the Good and his Burgundian troops took the city in a surprise attack by night.[5] This started a period of foreign rule for Luxembourg, which had been elevated from a County to a Duchy in 1354 by Charles IV.[5] Integrated into the territory of the Netherlands, it would be drawn into the duel between Valois-Bourbons and Habsburgs over the next few centuries, and was ruled by the Burgundians, the French, and the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs.[6]: 3 During this time the fortress was continually expanded and extended, and adapted to the military requirements of the day. The casemates, constructed by the Spanish and Austrians, are of particular note.[5]

By marriage, the fortress passed in 1447 to the Austrian Habsburgs along with all Burgundian possessions.[5] In 1542, the French troops of Francis I took the fortress, which was soon retaken by troops of the Holy Roman Empire.[5] Around 1545, Italian and Dutch engineers under Holy Roman Emperor Charles V built the first bastions, linked by curtain walls, on the site of the current Boulevard Roosevelt and Boulevard Royal. The ditch was enlarged from 13 to 31 metres. Ravelins were also added.[7]: 11

Spanish rule

[edit]Later, when the Spanish occupied the city, the aggressive policy of French King Louis XIV from 1670 led to the construction of additional fortifications.[7]: 11 (See also War of Devolution and War of the Reunions) With a French attack seeming imminent, the Spanish engineer Louvigny constructed several fortified towers in front of the Glacis from 1672, such as the Peter, Louvigny, Marie and Berlaimont Redoubts; he also built the first barracks in the city.[7]: 11 This formed a second line of defence around the city.[7]: 11 Louvigny also envisaged constructing works on the other side of the Pétrusse and Alzette valleys, but the Spaniards lacked the funds for this.[7]: 11 He had, however, anticipated what the French would do after 1684.[7]: 11

French siege and expansion under Vauban

[edit]

After the successful siege by Louis XIV in 1683-1684, French troops retook the fortress under the renowned commander and military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban. From 1684 to 1688, Vauban immediately started a massive re-building and expansion project for the fortifications, using more than 3,000 men.[5] Advance fortifications were placed on the heights around the city: the crownwork on Niedergrünewald, the hornwork on Obergrünewald, the "Corniche de Verlorenkost", Fort Bourbon and several redoubts.[7]: 11 He greatly expanded the military's hold over the urban space by integrating Pfaffenthal into the defences, and large barracks were built on the Rham and Saint-Esprit plateaux.[7]: 11 After the War of the Spanish Succession and the Peace of Ryswick, the fortress came under Spanish control from 1698,[8] then passed to French administration again in 1701.

Austrian period

[edit]In 1713 the Treaty of Utrecht gave Luxembourg to the Dutch, who ruled there for two more years before the fortress was retaken by Austrian troops in 1715, who remained in possession almost for the rest of the century.[5] The fortress of Luxembourg now formed one of the main strategic pillars in the defence of the Austrian Netherlands against French expansion.[5] For this reason, Vauban's fortifications were reinforced and extended.[5][7]: 11 It was under Charles VI and Maria Theresa that the fortress expanded the most in terms of surface area: the Austrian engineers added lunettes and several exterior forts (Olizy, Thüngen, Rubamprez, Rumigny, Neipperg, Wallis, Rheinsheim, Charles), closed off the valley with locks, and dug nearly 25 km of casemates into the bedrock.[5][7]: 11 The fortress now had a triple line of defences on all sides.[7]: 11

The Austrian engineer Simon De Bauffe was responsible for planning and carrying out this greatest expansion in the history of the fortress.[9]: 24

French Revolution and Prussian garrison

[edit]After an 11-month blockade, the city of Luxembourg was taken by French Revolutionary troops in 1795.[5] Subsequently, the Duchy of Luxembourg was integrated into the French Republic and later the French Empire as the "Département des Forêts".[5] In the aftermath of Napoleon's final defeat in 1815, the Congress of Vienna elevated Luxembourg to a Grand Duchy, now ruled in personal union by the King of the Netherlands. Simultaneously, Luxembourg became a member of the German Confederation, and the fortress became a "federal fortress". To this end, the Dutch King-Grand Duke agreed to share responsibility for the fortress with Prussia, one of two major German powers. While the Dutch King remained fully sovereign, Prussia received the right to appoint the fortress governor. The garrison would be made up of one-quarter Dutch troops and three-quarters Prussian troops.[10] As a result, until 1867, around 4,000 Prussian officers, NCOs and men were stationed amongst a community of about 10,000 civilian residents.[11] Notably, the fortress had already been garrisoned by Prussia since 8 July 1814, before the Congress of Vienna.[12]

The Prussians modernised the existing defences and added yet more advance forts, Fort Wedell and Fort Dumoulin.[7]: 11 There were even plans to build a fourth line of defences several kilometres from the city, to keep potential attackers even further at bay.[7]: 11 However, this was never implemented due to the demolition of the fortress in 1867 (see below).

Officially, the Prussian garrison in Luxembourg operated as an instrument of the German Confederation. Yet since Austria, the other major German power, had given up its possessions in the Low Countries, and Prussia had taken over the defence of the Western German states, Prussia's interests significantly overlapped with those of the Confederation. Prussia was also able to defend its own geopolitical interests at the same time.[12]: 87 The timeline of its occupation of the fortress underscores this: Prussia occupied the Luxembourg Fortress from 8 July 1814, before the Congress of Vienna had declared it a federal fortress on 9 June 1815, and before the Confederation even existed.[12]: 87 Only after 11 years of the Prussian garrison was the fortress formally taken over by the Confederation on 13 March 1826. Similarly, although the Confederation dissolved in 1866, Prussian troops did not leave the fortress until 9 September 1867.[12]: 87 Whether it was a federal fortress or not, Luxembourg was "the most Westerly bulwark of Prussia".[12]: 87

According to the military convention signed in Frankfurt am Main on 8 November 1816 between the Kings of the Netherlands and of Prussia, the Fortress of Luxembourg was to be garrisoned by 1/4 Dutch troops and 3/4 Prussian troops.[12]: 88 Article 9 stipulated that, in times of peace, the garrison should number 6,000 men, though this was temporarily lowered to 4,000 as the Allies were occupying France.[12]: 88 In practice, the level of 6,000 men was never reached.[12]: 88

In fact, the garrison consisted exclusively of Prussian troops: the Netherlands never provided their one-quarter of the garrison. Later, the Luxembourg-Prussian Treaty of 17 November 1856 gave Prussia the exclusive right to garrison troops in Luxembourg.[12]

In the 1830, the southern provinces of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands broke off to form the Kingdom of Belgium. At the outbreak of this Belgian Revolution, most Luxembourgers joined the rebels, and from 1830 to 1839, almost all of Luxembourg was administered as part of Belgium. The fortress and city of Luxembourg, held by the Dutch and Prussian troops, remained the only part of the country still loyal to the Dutch King William I. The stand-off was resolved in 1839, when the Treaty of London awarded the western part of Luxembourg to Belgium, while the rest, including the fortress, remained under William I.[13]: XVI

Luxembourg Crisis, Treaty of London and demolition

[edit]

After the Prussian victory in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, the German Confederation was dissolved. In its place, the North German Confederation was founded under Prussian leadership; it did not include Luxembourg. Nevertheless, Prussian troops continued to occupy the fortress. Before the war, the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck had signalled to the French government of Napoleon III that Prussia would not object to French hegemony in Luxembourg, if France stayed out of Prussia's conflict with Austria, to which Napoleon agreed. After the war, the French offered King William III 5,000,000 guilder for his personal possession of Luxembourg, which the cash-strapped Dutch monarch accepted in March 1867. Prussian objections, now portrayed this as French expansionism, provoked the Luxembourg Crisis. The threat of a major war between the major powers was averted only by the London Conference and the Second Treaty of London. This declared Luxembourg to be a neutral state, mandated the demolition of the fortress, and required the Prussian garrison to leave within three months. Prussian troops finally left on 9 September 1867.[12]

Typically, decommissioned fortresses were handed over to the respective cities. In Luxembourg, however, an urgent desire to comply with the Treaty of London and a fear of being caught up in a future Franco-German war prompted the government to spearhead the project on behalf of the city. The sale of fortress land financed the demolition costs and the urban development of the city. An international commission, inspecting the demolition work in 1883, brought to light the government's inexperience with such a project. The state had to decide between "keeping everything" and "razing everything". Military defensive works had to be broken up by roads; military remains converted into cellars or warehouses had to be destroyed.[14]: 336

Over 16 years, from 1867 to 1883, the fortress, including casemates, batteries, and barracks, was dismantled at a cost of 1.5 million francs. The process was somewhat chaotic: often parts of the fortress were simply blown up, the usable materials carried off by local residents, and the rest was covered up with earth. Social considerations were not overlooked, as old barracks served as housing for workers involved in the demolition. No qualification was required to participate in this work: during times of economic downturn, additional demolition projects on the fortress gave work to the unemployed. The dismantling became a grandiose spectacle, and a celebration of new technologies and ambitious projects.[14]: 337 Some buildings, however, were preserved for future generations (see below).

Luxembourg achieved full independence in 1890 after the death of the Dutch king William III. He was succeeded in the Netherlands by his daughter Wilhelmina but as the succession laws of Luxembourg allowed only male heirs, the personal union came to an end. The Luxembourg throne went to his nearest male relative, German Duke Adolphe of the House of Nassau-Weilburg who became Grand Duke.

Expansion of the city

[edit]While the demolition work undertaken might be viewed today as the dismantling of a historic monument, it was perceived at the time as an act of liberation. The fortress was the very visible symbol of foreign domination, and additionally its various masters of the fortress had restricted new construction to avoid influencing the defensive military strategy at the heart of the fortress. As the corset of the fortifications disappeared, the city could expand for the first time since the 14th century.

In the west the Boulevard Royal was built, running adjacent to the Municipal Park. In the south, the new Adolphe Bridge opened up the Bourbon Plateau for development, with its Avenue de la Liberté. This area witnessed the construction of a harmonious blend of houses, imposing edifices (the Banque et Caisse d'Épargne de l'État, the ARBED building, the central railway station) and squares such as the Place de Paris.[15]

Additionally, the residential quarters of Limpertsberg and Belair were created.

Layout

[edit]

In its final form, the fortress of Luxembourg consisted of three fortress walls, taking up about 180 ha (440 acres) at a time when the city covered only 120 ha (300 acres). Inside, there were a large number of bastions, with 15 forts in the centre, and another nine on the outside. A web of 23 km (14 mi) of underground passages (casemates) connected over 40,000 m2 (430,000 sq ft) of bomb-proof space. The epithet "Gibraltar of the North" compared the fortified city to the impregnable rock of Gibraltar. The fortress of Luxembourg was in fact never taken by force; in 1443, Philip the Good had taken it without opposition while subsequently the fortress was taken by siege leading to starvation.

The state of the fortress as of 1867 was as follows, in clockwise order: the Grünewald Front, facing north-east; the Trier Front, facing east; the Thionville Front, facing south, and the Front of the Plain or New Gate Front, facing west and north. These contained the following works:

|

|

|

|

- ^ Located between the current Avenue Jean-Pierre Pescatore and the Côte d'Eich

- ^ Vauban divided this Front into three smaller ones, describing the Jost-Camus Front as the Longwy Front, the Camus-Marie Front as the Marie Front and Marie-Berlaimont Front as the New Gate Front

- ^ Located on the current site of the Grand Théâtre de Luxembourg

Land usage

[edit]

In the Middle Ages, Luxembourg had been a relatively open city, with easy access through 23 gates. The ramparts delimited the urban space but allowed both people and goods to move between the town and the countryside without hindrance. This changed drastically from the mid-16th century, when fortifications cut the city off from the surrounding area.[7]

The defensive structures, spread out over a large distance, progressively hindered access to the city: the fortress became a straitjacket for its inhabitants. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the gaps in the old medieval defences were closed off. The Marie gate was buried under Bastion Marie in 1548, while the Lampert, Orvis, Beckerich and Jost gates disappeared in the early 17th century under the Berlaimont, Louis, Beck and Jost bastions.[7] The military logic behind the need for an inaccessible fortress contrasted with that in favour of a merchant city, open to the outside world. The 1644 closure of the Jews' gate, the primary access from the West facilitating trade with the Netherlands, was a key date in this process.[7] Traffic was obliged to bypass the plain, and enter by the New Gate (Porte-Neuve) built from 1626 to 1636. A traveller coming from France now had to descend into the Grund and come up through the Fishmarket, passing through several gates on the way.[7]

The Spanish government fully recognised that sealing off the city would stifle the economy and result in depopulation at a time when large numbers of civilians were needed to provide for the supply and lodging of the troops. Louvigny drew up plans in 1671 for a new gate on the rue Philippe and a bridge over the Pétrusse valley. These projects promised a significant boost in trade and transportation but were never realized, likely due to financial constraints.[7]

The fortress found itself encircled by a kind of no man's land, as the Austrians implemented a security perimeter in 1749, forbidding permanent constructions within. This was done to maintain a clear field of fire, an unobstructed view, and deny cover to potential attackers. Under the Prussians, the perimeter was extended to 979 m (3,212 ft) from the external lines of fortification.[7] Luxembourg's first railway station, built in 1859 on the Bourbon Plateau, fell within the perimeter, and therefore had to be constructed out of wood.[7]

The expansion of the fortress resulted in the loss of agricultural land. From the Middle Ages, gardens, orchards, fields, and meadows had encircled the city, forming a green belt. However, these gradually vanished to make room for fortifications.[7] The urban population, however, depended on this area for the city's supply of vegetables, fruit and fodder. The absorption of agricultural fields accelerated with the Austrian extension of the Glacis. Commander Neipperg had the earth removed down to the rock, a distance of 600 m (2,000 ft) from the fortress, so that attackers laying siege would have no opportunity to dig trenches.[7] The rocky desert that surrounded the city was now called the "bare fields" (champs pelés). Land expropriations often occurred without discussion, with the military invoking the threat of war and a state of emergency to seize plots without compensation. In 1744 for example, the garrison confiscated a plot of land close to the Eich gate in order to extend the defences. This land, and its garden of 48 fruit trees, belonged to three orphaned sisters, aged 9, 15 and 20, for whom the orchard was their only means of subsistence. The confiscation plunged them into destitution: when the soldiers chopped down the trees and the girls attempted to at least collect the firewood, they were chased away.[7]

It was not until the late 18th century that the authorities changed their attitude: the government in Brussels decided that compensation should be paid for confiscated property. The Austrians started to make up for the previous decades' injustices by making payments to those who had been expropriated, or to their descendants.[7]

Military rule

[edit]Entering or exiting the city meant passing under the watchful eye of the soldiers on guard duty.[7]: 13 At dusk, the gates would be shut, not to be re-opened until sunrise.[7]: 13 Fear of an attack was not the only reason for closing the gates at night. For long periods, especially in the late 18th century under Austrian rule, there was little likelihood of an attack.[7]: 13 Yet even in times of good relations with the neighbouring French, the doors were shut. The primary concern for military authorities was the persistent problem of troop desertion, a constant plague for all Ancien Régime garrisons.[7]: 13 Each year, a tenth of the Austrian troops would be lost to desertion, often escaping under the cover of darkness.[7]: 13 In 1765, barbed wire was placed on the ramparts, to make night-time escapes more difficult.[7]: 13 Paradoxically, the gate closure became more a matter of keeping the garrison inside than of protecting the city.[7]: 13 However, those still outside the walls would have to hurry home when they heard the Zapestreech—signalling the imminent gate closure—if they wanted to avoid being locked out for the night.[7]: 13 The Luxembourgish legend of Saint Nicholas (see below) refers to this.[7]: 13

Living conditions and relations between garrison and inhabitants

[edit]Lodging among civilians

[edit]

In a 1787 petition, the citizens of the city stated that they had "the sad privilege of living in a fortress, a privilege that is inseparable from the lodging of soldiers".[11]: 14 Living in a fortress city had serious disadvantages; the ramparts set strict limits on the amount of space available, while the inhabitants had to share this small area with large numbers of troops.[11]: 14 The further back one goes in history, the more difficult it is to locate exact numbers of both inhabitants and garrisoned soldiers.[11]: 15

For the Spanish period, in 1684 the Prince of Chimay commanded 2,600 soldiers, comprising 1,900 infantry and 700 cavalry.[11]: 15 The military population extended beyond troops; many soldiers and officers also had wives and children.[11]: 15 In 1655, one-third of the 660 soldiers in the upper town alone were listed as married, with about half having children.[11]: 15 Adding servants employed by officers, the total military population reached 1,170 — almost double the number of actual troops.[11]: 15

Under Austrian rule, some 2,700 troops were stationed in the fortress in 1722, as compared to 4,400 in 1741 and 3,700 in 1790. In times of crisis or war, the garrison might be increased dramatically, as in 1727-1732 when the Austrians feared a French attack and 10,000 soldiers were stationed inside the fortress or in camps in the surroundings (with the civilian population numbering only 8,000).[11] In the 19th century, 4,000 Prussian troops were garrisoned in a city of 10,000-13,000 residents.[11]

Housing such numbers was a logistical challenge. Until 1672, when the first barracks were constructed, all officers, troops, and their wives and children, lived with the civilian inhabitants, leading to drastic overpopulation. A magistrate in 1679 noted that there were only 290 houses in the city, many of them tiny, owned by poor artisans with large families. These people, who barely carved out a living from one week to the next, only just had enough beds to sleep in themselves, never mind providing accommodation for a large number of soldiers who were "crammed one on top of the other, experiencing first-hand the poverty and misery of their landlords".[11] The military's lists of billets give an idea of the cramped conditions in which troops and civilians co-existed: the butcher Jacques Nehr (listed in 1681) had a wife and five children. A room on the first floor of his house contained two married sergeants and three children. A second room housed a married soldier with his child, two gunners, and an infantryman. A dragoon lived above the stables. This was not an isolated case, and the justiciar and aldermen (échevins) repeatedly protested to the government about the intolerable living arrangements.[11]

Living in such close proximity caused tension between soldiers and residents. In 1679, a magistrate complained that citizens had to give over "three, four, five or six beds, along with linen and blankets" to "soldiers who were most often violent, drunk, and difficult, who mistreated them [...] stole their linen and furniture, and chased them from their own homes".[11] Ruffian soldiers would come home at night drunk, leaving the house doors open and being noisy. The Spanish troops were said to be particularly undisciplined. The introduction of barracks improved discipline but did not eliminate conflicts entirely. Complaints still arose in the 18th century about Austrian officers who moved into rooms more spacious than the ones they had been assigned; others would bring women of low repute to their house at night, to the alarm of their civilian landlords.[11]

This was especially galling since, under the Spaniards and Austrians, the city's inhabitants received no compensation for all this; they were to provide housing to the soldiers free of charge. The government claimed that since the garrison's presence brought trade and business which benefited the city's merchants and artisans, it was only fair for citizens to contribute by lodging the troops.[11] Nor was the burden of quartering troops shared equally, by any means. There were many exemptions, reflecting the social inequality of the Ancien Régime society. The justiciar, the aldermen, lawyers, members of the provincial council, and the nobility were exempt.[11] The magistrates assigned soldiers to houses, and to this effect made lists with very detailed descriptions of houses' interiors. This led to abuses of power: the authorities were known to assign excessive numbers of soldiers to houses of residents who had been involved in disputes with the city. Citizens tried to evade these obligations by deliberately keeping some rooms in their house unfit for habitation; the wealthier inhabitants could avoid housing soldiers by paying their way out.[11]

Introduction of barracks

[edit]

Purpose-built military accommodation was built in Luxembourg from 1672 onwards, with the barracks of Piquet and Porte-Neuve, along with huts on the Rham and Saint-Esprit plateaux.[11] The barracks were enlarged and multiplied by Vauban after 1684, and by the Austrians and Prussians over the next two centuries. In 1774, the six barracks housed 7,900 troops, with capacity for an additional 200 men in the military hospital in Pfaffenthal.[11] From the late 17th century, it became the norm for troops to reside in barracks, while officers continued to be quartered among civilians until the fortress's demolition in 1867. Even in Prussian times in the 19th century, most officers rented a room with their "servis", their accommodation allowance, ensuring house-owners at least received payment.[11]

By this point, under the Prussian garrison, most of the soldiers were only in Luxembourg for short periods in connection with their military service.[16] The aristocratic officers, on the other hand, were under strict social rules, and therefore intermarriages between the civilian population and the garrison soldiers were uncommon, except for non-commissioned officers, who were career soldiers.[16] There was a love-hate relationship between inhabitants and garrison: on the one hand, there was jealousy over the soldiers' exemption from certain taxes and levies; on the other, the soldiers spent their wages in the city, and many businessmen and shopkeepers depended on the military for their livelihood, as did the craftsmen and day labourers who worked on improving or repairing the fortifications.[16]

Both groups suffered the same poor living conditions in the city, such as the lack of a clean water supply and of sanitation, leading to outbreaks of cholera and typhus. The cramped barracks often required two soldiers to share a bed. Officers, quartered in the houses of the upper classes, did not experience such problems. This stratification was mirrored among the inhabitants: there was a marked difference between the dark, cramped housing of the poor in the lower town and the fine accommodation enjoyed by the rich who lived in housing in the upper town built by the nobility or the clergy.[16]

Animals

[edit]

Animals played a vital role in the upkeep and functioning of a fortress, as well as in feeding its garrison. Riding horses, draught horses and workhorses were required while cattle, sheep or other animals were needed for slaughter.[17]

In 1814, the ground floors of the Rham Barracks, the Maria Theresa Barracks, and the riding barracks were renovated for use as stables. Out of the five storage buildings for grain and flour which had been built by 1795, the one in the upper town was used as a stable. Together, these had a capacity of 386 horses.[17] By late 1819, the artillery required a new riding arena to train the large number of new horses that were being delivered. For this, they wanted to use the garden of an old monastery on the Saint-Esprit Plateau. By 1835, an indoor riding arena in the lower yard of the plateau had been completed. This had enough room to train a squadron, and in war time could be used as a livestock shed or as a fodder store.[17]

Beyond the riding horses of the cavalry detachment and officers, a large number of draught horses belonged to the artillery and military engineers to ensure supplies. In case of emergency or when large-scale transport was necessary, contracts were signed with private haulage companies. The mill in the Cavalier Camus alone, which made enough flour daily for 1,500 portions of bread, required 24 horses to operate.[17] Horse artillery units were ready for rapid reinforcement of endangered fortress sections or to support a breakout. In 1859, Luxembourg boasted eight horse guns with 38 horses. Additional horses were also needed to transport ammunition, as well as for riding and as reserves.[17]

Storage space for the animals' fodder had to be found. Oats were stored in the remaining churches after 1814. Straw posed a problem due to fire hazards, leading to its storage either in the trenches of the Front of the plain, in Pfaffenthal, or in the lower quarters of the Grund and Clausen.[17] The livestock intended for slaughter were to be accommodated among the inhabitants, with the gardens in the Grund and Pfaffenthal being reserved for cattle.[17]

Animals could also be a source of income for the military: already under the French, the fortress authorities sold off the grazing rights on the grassy areas of the Glacis. Due to lax supervision of grazing, however, by 1814, some of the folds were no longer recognisable as such.[17]

Legacy

[edit]Remains and later use

[edit]

Parts of the fortress were not destroyed after 1867, but simply rendered unfit for military use. Many old walls and towers still survive, and still heavily influence the view of the city. Some of the remaining elements of the fortress are the Bock promontory,[18] Vauban towers, the "Three Towers" (one of the old gates),[19] Fort Thüngen, the towers on the Rham plateau,[20] the Wenceslas Wall,[21] the old cavalry barracks in Pfaffenthal,[22] the Holy Ghost citadel, the casemates of the Bock and the Pétrusse,[23][24] the castle bridge, and some of the Spanish turrets.[25] The modern-day city depends very heavily for its tourism industry on its location as well as promoting the remains of the fortress and the casemates.[26] The Wenceslas and Vauban circular walks have been set up to show visitors the city's fortifications.[27][28][29][30] The old fortifications and the city have been classed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1994.[3]

The old Fort Thüngen on the Kirchberg plateau has been heavily restored, and now houses the Museum of the Fortress.[31]

Fort Lambert, on the Front facing the plain, was covered over with earth after 1867. On this site, the Avenue Monterey was built. In 2001, construction work on an underground car park under the Avenue Monterey uncovered part of the Fort – one of its redoubts – which can now be seen by the public.[32]

Bastion Beck is now the Place de la Constitution, where the iconic Gëlle Fra statue is located.[33]

From 2003-2008 the National Centre for Archaeological Research (French: Centre National de Recherche Archéologique) (CNRA) carried out large-scale archaeological works in the area of the Wenceslas Wall.[9] In 2009, the Service des Sites et Monuments nationaux (SSMN) drew up plans for the restoration of this part of the fortress.[9] The works themselves took place from 2010-2014, and the site was ceremonially inaugurated on 30 July 2015.[9]

From 2008-2009, archaeological excavations took place on the site of the “Fort du Moulin”, which were necessary due the construction of the headquarters of the FNEL.[9] Researchers were able to analyse large parts of the Fort.[9] The excavated parts were covered back up with earth after the dig.[9]

In the area of Fort Rumigny, the old French “Redoute de la Bombarde” (the later “Réduit Rumigny”) was restored and converted from 2000-2017 by the Service des Sites et Monuments nationaux.[9] It is now the seat of the “Frënn vun der Festungsgeschicht Lëtzebuerg a.s.b.l.” association (Lux.: Friends of the History of the Fortress of Luxembourg).[9]

From 2011-2012 parts of the righthand-rear trench and the redoubt of Fort Rumigny were analysed by the CNRA. These works were necessary due to the construction of the new "Sportlycée” at the Institut National des Sports.

Place names

[edit]Many street and building names in the city still serve as a reminder of the city's former military function, the defensive works, and of the foreign troops and administrators in Luxembourg:

- Rue du Fort Rheinsheim, and the nearby "Salle Rheinsheim" of the Centre Convict (a meeting-place for religious and cultural organisations); also the headquarters of the "S.A. Maria Rheinsheim", which administers the real estate of the Catholic Church in Luxembourg[34]

- Rue du Fort Dumoulin

- Rue du Fort Olisy

- Rue Louvigny and the Villa Louvigny, which was built on the remains of Fort Louvigny, named after Jean Charles de Landas, Count of Louvigny, who was chief engineer and interim governor of the fortress in the 1670s[35]

- Rue du Fossé (fossé: ditch)

- Place d'Armes, French for "parade ground"

- Rue Malakoff

- Avenue de la Porte-Neuve, after the "New Gate" (French: Porte Neuve)

- Avenue Émile-Reuter was until 1974 called the Avenue de l'Arsenal (Lux: Arsenalstrooss, which is still used by some today), after an artillery detachment there

Street sign for Rue Louvigny. The explanation reads "Military engineer in the Spanish period, 1675". - Rue Jean-Georges Willmar, named after a governor of Luxembourg (1815-1830)[36]

- Rue Vauban (in Clausen), after Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, the French military engineer who massively expanded Luxembourg's fortifications[37]

- The Glacis and the Rue des Glacis, a glacis being a slope of earth in front of defensive fortifications

- Boulevard Kaltreis (in Bonnevoie), used to be colloquially called "op der Batterie", as the French troops besieging the city had positioned their artillery here in 1794[38]

- On the Bourbon plateau, itself named after Fort Bourbon:[39]

- Rue du Fort Bourbon[40]

- Rue du Fort Elisabeth [41]

- Rue du Fort Wallis[42]

- Rue du Fort Neipperg, after Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg, an Austrian general who was governor of Luxembourg five times in the 18th century[43]

- Rue Bender, after Blasius Columban von Bender, governor from 1785 to 1795[44]

- Rue du Fort Wedell

- On the Kirchberg plateau:

- Rue des Trois Glands and Rue du Fort Thüngen; the Fort, which has been mostly reconstructed, consists of three towers, hence nicknamed the "Three Acorns" (French: Trois Glands)[45]

- Rue du Fort Berlaimont[46]

- Rue du Fort Niedergrünewald

Culture and folklore

[edit]A local version of a legend of Saint Nicholas (D'Seeche vum Zinniklos) refers to the danger of being shut outside the fortress gates for the night.[7]: 13 Three boys were playing outside, and were far away from the city when the curfew was sounded: it was too late for them to return home.[7]: 13 They sought refuge with a butcher who lived outside the city.[7]: 13 At night-time, however, the butcher killed them to turn them into aspic.[7]: 13 Luckily, a few days later, Saint Nicholas also found himself shut out of the city, and went to the same butcher's house.[7]: 13 He found the children, and was able to bring them back to life.[7]: 13

Jean Racine, the famous French dramatist, was in Luxembourg in 1687 as the historiographer of Louis XIV and inspector of the fortress.[47]

There are several elaborate maps and views of the fortress made before 1700. In 1598, Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg published the oldest known view of Luxembourg City, a copper engraving that appeared in Civitates orbis terrarum (Cologne, 1598). Half a century later, the Dutch cartographer Joan Blaeu, drawing on Braun's work, published his "Luxemburgum" in the second volume of his Stedeboek (Amsterdam, 1649). Van der Meulen provides another view of Luxembourg from Limpertsberg where he depicts French troops taking the city in 1649.[48]

In more modern times, the British Romantic landscape artist J. M. W. Turner (1775-1851) painted several scenes of the fortress, both paintings and sketches, after visiting in 1824 and 1839. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe visited the city in 1792, and left a number of sketches of the fortress. Christoph Wilhelm Selig, a member of the Hessian garrison (1814-1815), painted several watercolours. Later, the fortress served as a model for the Luxembourgers Michel Engels and Nicolas Liez and Jean-Baptiste Fresez. Even after the dismantling of (most of) the fortifications by 1883, the spectacular remains have still been used as motifs by artists such as Joseph Kutter or Sosthène Weis.

-

Georg Braun, Franz Hogenberg: Luxembourg City (1598)

-

Joan Blaeu: Luxembourg City (1649)

-

Van der Meulen: Prise de Luxembourg (1684)

-

Christoph Wilhelm Selig: Luxembourg from Pfaffenthal (1814)

-

Jean-Baptiste Fresez: Luxembourg from the Alzette River (c. 1828)

-

J. M. W. Turner: Luxembourg (1834)

-

J. M. W. Turner: Citadel of St Esprit, Luxembourg (c. 1839)

-

Nicolas Liez: View of Luxembourg from the Fetschenhof (1870)

-

Sosthène Weis: Bock rock (1938)

See also

[edit]- Fort Thüngen

- Siege of Luxembourg (1684)

- Siege of Luxembourg (1794–95)

- Fortresses of the German Confederation

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Kreins, Jean-Marie. Histoire du Luxembourg. 3rd edition. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2003. ISBN 978-2-13-053852-3. p. 64.

- ^ Merlin, P. Antoine (1795). Collections des discours prononcé à la Convention nationale.

- ^ a b "City of Luxembourg: its Old Quarters and Fortifications". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ Lodewijckx, Marc (1 January 1996). Archaeological and historical aspects of West-European societies: album amicorum André Van Doorselaer. Leuven University Press. pp. 379–. ISBN 978-90-6186-722-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "History: From castle to fortress". Ville de Luxembourg. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ a b Thewes, Guy (2008). About … History of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (PDF). Luxembourg: Service information et presse. ISBN 978-2-87999-119-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am Thewes, Guy (2012). "Le "grand renfermement" - La ville à l'âge de la forteresse" (PDF). Ons Stad (in French) (99): 10–13. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 952; second para, lines three and four.

....while Spain recovered Catalonia, and the barrier fortresses of Mons, Luxemburg and Courtrai.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wagner, Rob (2018). "D'Festungswierker vun der Tréierer Front" (PDF). Ons Stad (in Luxembourgish) (119). Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ Engelhardt, Friedrich Wilhelm. Geschichte der Stadt und Festung Luxemburg: Seit ihrer ersten Entstehung bis auf unsere Tage. Luxembourg: Rehm, 1830. p. 284-285

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Thewes, Guy (2013). "Le logement des soldats dans la forteresse de Luxembourg - "Dansons et sautillons ensemble dans la chambre"" (PDF). Ons Stad (in French) (102): 14–17. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Carmes, Alex. "Die Zusammensetzung der Garnison" (in German). In: Musée d'Histoire de la Ville de Luxembourg (ed.). Das Leben in der Bundesfestung Luxemburg (1815-1867). Luxembourg: Imprimerie Centrale, 1993. pp. 87ff

- ^ Fyffe, Charles Alan. A History of Modern Europe, 1792-1878. Popular edition, 1895. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ a b Philippart, Robert. "La Ville de Luxembourg: De la ville forteresse à la ville ouverte entre 1867 et 1920." Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in French) In: Emile Haag. Une réussite originale - Le Luxembourg au fil des siècles. Luxembourg: Binsfeld, 2011.

- ^ "History - After the dismantling of its fortress". Luxembourg City Tourist Office. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d Jungblut, Marie-Paule. "Das Leben in der Bundesfestung Luxemburg 1815-1867." (in German) Ons Stad, No. 43, 1993. p. 6-7

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bruns, André. "Tiere in der Festung." (in German) Ons Stad, No. 97, 2011. p. 48-49

- ^ "Bock Promontory". Luxembourg City Tourist Office, 2013.

- ^ "Les 3 tours" Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (in French) Service des Sites et Monuments Nationaux, 2010.

- ^ "Rham Plateau". Luxembourg City Tourist Office, 2013.

- ^ "Wenceslas Wall". Luxembourg City Tourist Office, 2013.

- ^ "Ancienne caserne de cavalerie (Pfaffenthal)" Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (in French) Service des Sites et Monuments Nationaux, 2009.

- ^ "Petrusse Casemates". Luxembourg City Tourist Office, 2013.

- ^ "Bock Casemates". Luxembourg City Tourist Office, 2013.

- ^ "Spanish Turret" Luxembourg City Tourist Office, 2013.

- ^ "After the dismantling of its fortress" Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Luxembourg City Tourist Office, 2013.

- ^ "Itinéraire culturel Wenzel" Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (in French) Service des Sites et Monuments Nationaux, 2010.

- ^ "Itinéraire culturel Vauban" Archived 19 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (in French) Service des Sites et Monuments Nationaux, 2010.

- ^ "Promenades - The Wenzel Circular Walk" Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Luxembourg City Tourist Office, 2013.

- ^ "Promenades - The Vauban Circular Walk" Archived 2 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Luxembourg City Tourist Office, 2013.

- ^ Historique du bâtiment (in French) Musée Dräi Eechelen, 2012.

- ^ Redoute Lambert - Parking Monterey Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine (in French) Service des sites et monuments nationaux, 2009.

- ^ Bastion Beck - Place de la Constitution Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine (in French) Service des sites et monuments nationaux, 2009.

- ^ Beck, Henri. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Rheinsheim (Rue du Fort) (in German) Ons Stad, No. 54, 1997. p. 32

- ^ Friedrich, Evy. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Louvigny (Rue) (in German) Ons Stad, No. 21, 1986. p. 34

- ^ Beck, Fanny. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Willmar (Rue Jean-Georges)". (in German) Ons Stad, No. 102, 2013. p. 71

- ^ Beck, Fanny."Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Vauban (Rue)". (in German) Ons Stad, No. 92, 2009. p. 67

- ^ Friedrich, Evy. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Kaltreis (Boulevard)". (in German) Ons Stad, No. 16, 1984. p. 26

- ^ "Bourbon Plateau - LCTO". www.luxembourg-city.com. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Friedrich, Evy. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Bourbon (Rue du Fort)". (in German) Ons Stad, No. 4, 1980. p. 36

- ^ Friedrich, Evy; Holzmacher, Gaston. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Elisabeth (Rue du Fort)". (in German) Ons Stad, No. 8, 1981. p. 27

- ^ Beck, Fanny. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Wallis (Rue du Fort)". (in German) Ons Stad, No. 95, 2010. p. 55

- ^ Friedrich, Evy; Beck, Henri. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Neipperg (Rue du Fort)". (in German) Ons Stad, No. 29, 1988. p. 30

- ^ Friedrich, Evy. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Bender (Rue). (in German) Ons Stad, No. 3, 1980. p. 27

- ^ Beck, Fanny. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Trois Glands (Rue des)". (in German) Ons Stad, No. 88, 2008. p. 68

- ^ Friedrich, Evy. "Was bedeuten die Straßennamen der Stadt? - Berlaimont (Rue du Fort)". (in German) Ons Stad, No. 3, 1980. p. 29

- ^ "Arts et culture au Luxembourg: Une culture ouverte sur le monde." Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine Service information et presse du gouvernement luxembourgeois, 2009.

- ^ Mersch, Jacques. "Luxembourg: vues ancienne". Luxembourg: Editions Paul Bruck, 1977. (in French)

References and further reading

[edit]- Bruns, André. Luxembourg as a Federal Fortress 1815-1860. Wirral: Nearchos Publications, 2001.

- Bruns, André (1 July 2005), "Le siège de Luxembourg en 1684. Organisation et logistique.", Hémecht (in French), vol. 57, no. 3, retrieved 30 October 2023

- Clesse, René. "300 Jahre Plëssdarem" (in German). Ons Stad, No 37, 1991. p. 5-11

- Coster, J. (1869). Geschichte der Festung Luxemburg seit ihrer Entstehung bis zum Londoner-Traktate von 1867: Mit besonderer Rücksicht auf die strategische Bedeutung und die kriegsgeschichtlichen Ereignisse dieses Platzes. Nebst einem Plan mit sammtl. Festungswerken. V. Bück.

- Deidier (1742). Le parfait ingénieur françois, ou La fortification offensive et défensive; contenant la construction, l'attaque et la défense des places régulieres & irrégulieres, selon les méthodes de monsieur De Vauban, & des plus habiles auteurs de l'Europe, qui ont écrit sur cette science. Charles-Antoine Jombert. pp. 167–.

- Dondelinger, Patrick (1 January 2008), "Le glacis de la forteresse de Luxembourg, lieu(e) de mémoire nationale", Hémecht (in French), vol. 60, no. 1, pp. 5–78, retrieved 29 October 2023

- Engelhardt, Friedrich Wilhelm (1830). Geschichte der Stadt und Festung Luxemburg: seit ihrer ersten Entstehung bis auf unsere Tage : mit besonderer Rücksicht auf die kriegsgeschichtlichen Ereignisse; nebst Plan der Stadt und statistischer Einleitung. Rehm.

- Engels, Michel. Bilder aus der ehemaligen Bundesfestung Luxemburg. Luxembourg: J. Heintzes Buchhandlung, 1887.

- Jacquemin, Albert. Die Festung Luxemburg von 1684 bis 1867. Luxembourg, 1994.

- Knaff, Arthur (1887). Die Belagerung der Festung Luxemburg durch die Franzosen unter Maréchal de Créqui im Jahre 1684: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Festung Luxemburg ; mit einer Karte. Heintze.

- Koltz, Jean-Pierre. Baugeschichte der Stadt und Festung Luxemburg. Luxembourg, Vol. I, 1970.

- Konen, Jérôme (ed.) Kasematten - Auf Spurensuche in der Festungsstadt Luxemburg. Luxembourg: Jérôme Konen Productions, 2013.

- Kutter, Edouard. Luxembourg au temps de la forteresse. Luxembourg: Edouard Kutter, 1967.

- Margue, Paul (1 April 1967). "Wirtschaftsnotizen zur Demilitarisierung der Stadt Luxemburg". Hémecht (in German). 19 (2): 167ff.

- May, Guy. "Die Militärhospitäler der früheren Festung Luxemburg". Ons Stad, No. 100, 2012. p. 76-79

- Musée d'Histoire de la Ville de Luxembourg (ed.). Das Leben in der Bundesfestung Luxemburg (1815-1867). Luxembourg: Imprimerie Centrale, 1993.

- Mersch, François. Luxembourg. Forteresse & Belle Epoque. Luxembourg: Éditions François Mersch, 1976.

- Parent, Michel. Vauban. Paris: Editions Jacques Fréal, 1971.

- Pauly, Michel; Uhrmacher, Martin: "Burg, Stadt, Festung, Großstadt: Die Entwicklung der Stadt Luxemburg". / Yegles-Becker, Isabelle; Pauly, Michel: "Le démantelement de la forteresse". In: Der Luxemburg Atlas – Atlas du Luxembourg. Eds.: Patrick Bousch, Tobias Chilla, Philippe Gerber, Olivier Klein, Christian Schulz, Christophe Sohn and Dorothea Wiktorin. Photos: Andrés Lejona. Cartography: Udo Beha, Marie-Line Glaesener, Olivier Klein. Cologne: Emons Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-89705-692-3.

- Pays, A. S. Du (1863). Itinéraire descriptif, historique, artistique et industriel de la Belgique. Hachette et Cie. pp. 323–.

- Philippart, Robert L. (2012). "1867-1920: Stadt- oder Staatsplanung für das neue Luxemburg?" (PDF). Ons Stad (in German) (99).

- Prost, Philippe. La ville en guerre. Édition de l'imprimeur, 1996.

- Reinert, François (2022). ""Do weist de Fuuss e Schloff mer, En nennt et Kasematt"" (PDF). Ons Stad (in German) (126): 11–14.

- Rocolle, Pierre. 2000 ans de fortification française. Lavauzelle, 1989.

- Rupprecht, Alphonse. Logements militaires à Luxembourg pendant la période de 1794 à 1814. Luxembourg: Krippler-Muller, 1979.

- Savin, Cyril. Musée de la Forteresse, Conception générale d’aménagement thématique. Luxembourg: Service des Sites et Monuments Nationaux, 1998.

- Thewes, Guy. Luxembourg Forteresse d’Europe, catalogues du Musée d’Histoire de la ville de Luxembourg, Vol. 5. Luxembourg, 1998.

- Thewes, Guy; Wagener, Danièle. "La Ville de Luxembourg en 1795". (in French) Ons Stad, No. 49, 1995. p. 4–7.

- Thewes, Guy. "Les casernes du Rham" (in French) Ons Stad, No. 53, 1996. p. 3-5

- Thewes, Guy. "L'évacuation des déchets de la vie urbaine sous l'Ancien Régime" (in French). Ons Stad, No. 75, 2004. p. 30–33.

- Thewes, Guy. "Luxembourg, ville dangereuse sous l’Ancien Régime? - Police et sécurité au XVIIIe siècle" (in French). Ons Stad, No. 104, 2013. p. 58–61.

- Tousch, Pol. Episoden aus der Festung Luxemburg: Luxembourg, une forteresse raconte. Luxembourg: Éditions Pol Tousch, 1998. ISBN 2-919971-05-0.

- Trausch, Gilbert. La Ville de Luxembourg, Du château des comtes à la métropole européenne. Fonds Mercator Paribas, 1994. ISBN 978-9-06153-319-1.

- Trausch, Gilbert (1994). Du château du Bock au Gibraltar du Nord. Luxembourg et sa forteresse (PDF) (in French). Banque de Luxembourg.

- Van der Vekene, Emile. Les plans de la ville et forteresse de Luxembourg édités de 1581 à 1867. 2nd edition. Luxembourg: Saint-Paul, 1996. ISBN 978-2-87963-242-1.

- Watelet, Marcel. Luxembourg Ville Obsidionale, Musée d’Histoire de la ville de Luxembourg. Luxembourg, 1998.

- Zimmer J. Le Passé Recomposé, archéologie urbaine à Luxembourg. Luxembourg, MNHA, 1999.

- Zimmer J. Aux origines du quartier St-Michel à Luxembourg "Vieille ville", De l’église à la ville. Luxembourg, MNHA, 2001.

External links

[edit]- FFGL: Frënn vun der Festungsgeschicht Lëtzebuerg - a.s.b.l. (in French)

- Luxembourg City Tourist Office

- Musée Dräi Eechelen (in French), the fortress museum

- Forteresse de Luxembourg Archived 10 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in French) on the "Service des sites et monuments nationaux" website

- Fortified Places, Luxembourg Archived 10 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine