Hourglass: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→History: hourglass origins |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

<!-- Punctuation in quote as original. Do not edit --> |

<!-- Punctuation in quote as original. Do not edit --> |

||

{{clear}} |

{{clear}} |

||

A much earlier origin of Hourglass motif used on [[Midewiwin]] [[Wiigwaasabak]] was suggested by Greenman. "A prominent feature of the pictorial art of the Algonquians around Lake Superior and Michigan is the use of an hourglass shape to portray the human form. There are many examples of it on birch bark records and in drawings made by Indian Informants. They seem to be derived ultimately from the [[upper paleolithic]] figures." Several arguments were included in the same issue. Juan Schobinger wrote in reply "A detailed analysis of the comparisons and the accompanying illustrations show Greenman to be even more incorrect. I shall only discuss some critical facts on rock-painting and engraving. The hourglass shape has nothing to do with palaeolithic art...". Greenman stated stated in response to Schobinger: "Schobinger says the double curve motif is world-wide. I do not question that, but I know of no group of them that have the specific character of those of the Algonquian and the Upper Paleolithic of Spain."<ref>Greenman, E.F. 1963. The Upper Paleolithic and the New World. Current Anthropology. Vol. 4. No. 1. pp 41-91.</ref> The Winnebago utilized reciprocal hourglass patterns on their fiber bags as an abstract assemblage of human figures, as did the Makusi Indians of Guiana on beaded apron, and the hourglass is seen on engraved shell from Argentina.. "It is the result of a constantly refined tradition. Over ten thousand years of history lie behind that design, Not by borrowing and not by invention, but only by long inheritance can we explain these widespread, remarkable parallels." <ref>Schuster,Carl and Edmund Carpenter. 1996. Patterns that Connect. Social Symbolism in Ancient and Tribal Art. Harry N. Abrams Inc,Publishers. ISBN 0-8109-6326-4.</ref> |

|||

==Practical uses== |

==Practical uses== |

||

Revision as of 05:57, 1 July 2008

An hourglass, also known as a sandglass, sand timer or sand clock, is a device for the measurement of time. It consists of two glass bulbs placed one above the other which are connected by a narrow tube. One of the bulbs is usually filled with fine sand which flows through the narrow tube into the bottom bulb at a given rate. Once all the sand has run to the bottom bulb, the device can be inverted in order to measure time again. The hourglass is named for the most frequently used sandglass, where the sands have a running time of one hour.[citation needed]

Factors affecting the amount of time that the hourglass measures include: the volume of sand, the size and angle of the bulbs, the width of the neck, and the type and quality of the sand. Alternatives to sand that have been used are powdered eggshell and powdered marble.[1] (Sources do not agree on the best internal material.)

Hourglasses are still in use, but typically only ornamentally or when a relatively approximate measurement of time is needed, as in egg timers for cooking or board games. Hourglass collecting has become a niche but avid hobby for some, with elaborate or antique hourglasses commanding high prices.

History

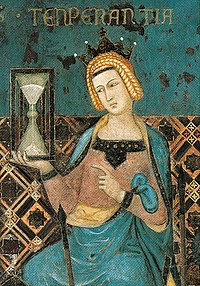

Hourglasses are said to have been invented at Alexandria about the middle of the third century, where they were sometimes carried around as people carry watches today.[2] It is speculated that it was in use in the 11th century, where it would have complemented the magnetic compass as an aid to navigation. Glassmaking was brought to Europe in the thirteenth century by the Venetians, who created notable sandglasses. Recorded evidence of their existence is found no earlier than the 14th century, the earliest being an hourglass appearing in the 1338 fresco Allegory of Good Government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti.[3] Written records from the same period mention the hourglass, and it appears in lists of ships stores. One of the earliest surviving records is a sales receipt of Thomas de Stetesham, clerk of the English ship La George, in 1345:

The same Thomas accounts to have paid at Lescluse, in Flanders, for twelve glass horologes (" pro xii. orlogiis vitreis "), price of each 4½ gross', in sterling 9s. Item, For four horologes of the same sort (" de eadem secta "), bought there, price of each five gross', making in sterling 3s. 4d.[4]

A much earlier origin of Hourglass motif used on Midewiwin Wiigwaasabak was suggested by Greenman. "A prominent feature of the pictorial art of the Algonquians around Lake Superior and Michigan is the use of an hourglass shape to portray the human form. There are many examples of it on birch bark records and in drawings made by Indian Informants. They seem to be derived ultimately from the upper paleolithic figures." Several arguments were included in the same issue. Juan Schobinger wrote in reply "A detailed analysis of the comparisons and the accompanying illustrations show Greenman to be even more incorrect. I shall only discuss some critical facts on rock-painting and engraving. The hourglass shape has nothing to do with palaeolithic art...". Greenman stated stated in response to Schobinger: "Schobinger says the double curve motif is world-wide. I do not question that, but I know of no group of them that have the specific character of those of the Algonquian and the Upper Paleolithic of Spain."[5] The Winnebago utilized reciprocal hourglass patterns on their fiber bags as an abstract assemblage of human figures, as did the Makusi Indians of Guiana on beaded apron, and the hourglass is seen on engraved shell from Argentina.. "It is the result of a constantly refined tradition. Over ten thousand years of history lie behind that design, Not by borrowing and not by invention, but only by long inheritance can we explain these widespread, remarkable parallels." [6]

Practical uses

Hourglasses were the first dependable, reusable and reasonably accurate measure of time. The rate of flow of the sand is independent of the depth in the upper reservoir, and the instrument is not liable to freeze.[7]

From the 15th century onwards, they were being used in a wide range of applications at sea, in the church, in industry and in cookery.

During the voyage of Ferdinand Magellan around the globe, his vessels kept 18 hourglasses per ship. It was the job of a ship's page to turn the hourglasses and thus provide the times for the ship's log. Noon was the reference time for navigation, which did not depend on the glass, as the sun would be at its zenith.[8] More than one hourglass was sometimes fixed in a frame, each with a different running time, for example 1 hour, 45 minutes, 30 minutes, and 15 minutes.

Modern practical uses

While they are no longer widely used for keeping time, some institutions do maintain them. Both houses of the Australian Parliament use three hourglasses to time certain procedures, such as divisions.[9]

The sandglass is still widely used as the kitchen egg timer; for cooking eggs, a three minute timer is typical,[10] hence the name "egg timer" for three minute hourglasses. Egg timers are sold widely as souvenirs,[citation needed] and games such as Boggle also make use of it.

Symbolic uses

Unlike most other methods of measuring time, the hourglass concretely represents the present as being between the past and the future,[citation needed] and this has made it an enduring symbol of time itself.

The hourglass, sometimes with the addition of metaphorical wings, is often depicted as a symbol that human existence is fleeting, and that the "sands of time" will run out for every human life.[11] It was used thus on pirate flags, to strike fear into the hearts of the pirates' victims. In England, hourglasses were sometimes placed in coffins,[12] and they have graced gravestones for centuries.

Modern symbolic uses

Recognition of the hourglass as a symbol of time has survived its obsolescence as a timekeeper. For example, the American television soap opera Days of our Lives, since its first broadcast in 1965, has displayed an hourglass in its opening credits, with the narration, "Like sands through the hourglass, so are the days of our lives."

Various computer programs and earlier versions of Windows may change the mouse cursor to an hourglass during a period when the program is in the middle of a task, and may not accept user input. During that period other programs, for example in different windows, may work normally. When a Windows hourglass does not disappear, it suggests a program is in an infinite loop and needs to be terminated, or is waiting for some external event (such as the user inserting a CD).

See also

- Timewheel, a one-year hourglass

References

- ^ Madehow.com (2006). "Hourglass". How Products Are Made, vol. 5. Madehow.com. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ^ The Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar. W. & R. Chambers, Ltd.

- ^ Frugoni, Chiara (1988). Pietro et Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Scala Books. p. 83. ISBN 0935748806.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Nicolas, Nicholas Harris (1847). A history of the Royal navy, from the earliest times to the wars of the French revolution, vol. II. London: Richard Bentley. p. 476.

- ^ Greenman, E.F. 1963. The Upper Paleolithic and the New World. Current Anthropology. Vol. 4. No. 1. pp 41-91.

- ^ Schuster,Carl and Edmund Carpenter. 1996. Patterns that Connect. Social Symbolism in Ancient and Tribal Art. Harry N. Abrams Inc,Publishers. ISBN 0-8109-6326-4.

- ^ Mills, A.A.; Day, S.; Parkes, S. (1996), "Mechanics of the sandglass" (PDF), European Journal of Physics, vol. 17, pp. 97–109, doi:10.1088/0143-0807/17/3/001

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Bergreen, Laurence (2003). Over the Edge of the World: Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe. William Morrow. ISBN 0066211735.

- ^ Senate of Australia (26 March 1997). "Official Hansard" (PDF): 2472.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Herbst, Sharon Tyler (2001). The New Food Lover's Companion. Barron's Educational Series.

- ^ Room, Adrian (1999). Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. New York: HarperCollinsPublishers. "Time is getting short; there will be little opportunity to do what you have to do unless you take the chance now. The phrase is often used with reference to one who has not much longer to live. The allusion is to the hourglass."

- ^ Ewbank, Thomas (1857). A Descriptive and Historical Account of Hydraulic and Other Machines for Raising Water, Ancient and Modern With Observations on Various Subjects Connected with the Mechanic Arts, Including the Progressive Development of the Steam Engine. Vol. 1. New York: Derby & Jackson. p. 547. "Hour-glasses were formerly placed in coffins and buried with the corpse, probably as symbols of mortality—the sands of life having run out. See Gent. Mag. vol xvi, 646, and xvii, 264."

Further reading

Books

- Branley, Franklyn M. (1993), Keeping time: From the beginning and into the twenty-first century, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Cowan, Harrison J. (1958), Time and its measurement: From the stone age to the nuclear age, New York: The World Publishing Company

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Guye, Samuel; Henri, Michel (1970), Time and space: Measuring instruments from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, New York: Praeger Publishers

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Smith, Alan (1975), Clocks and watches: American, European and Japanese timepieces, New York: Crescent Books

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Periodicals

- Morris, Scot (September 1992), "The floating hourglass", Omni, p. 86

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Peterson, Ivars (September 11, 1993), "Trickling sand: how an hourglass ticks", Science News

{{citation}}: Text "167" ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link)

External links

- Brief History, a detailed history of the invention and construction of hourglasses at hourglasses.com

- Hourglass History, at the site of Tom Young, hourglass maker

- Allegory of Good Government at aiwaz.net