Fibonacci sequence: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

Please discuss on talk page Undid revision 237677478 by Jean-claude perez (talk) |

||

| Line 678: | Line 678: | ||

*[[Negafibonacci]] numbers |

*[[Negafibonacci]] numbers |

||

*[[Lucas number]] |

*[[Lucas number]] |

||

*[[Fibonacci numbers and Fractals]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 692: | Line 691: | ||

* Donald E. Simanek, ''[http://www.lhup.edu/~dsimanek/pseudo/fibonacc.htm Fibonacci Flim-Flam]'', (undated, 2005 or earlier). |

* Donald E. Simanek, ''[http://www.lhup.edu/~dsimanek/pseudo/fibonacc.htm Fibonacci Flim-Flam]'', (undated, 2005 or earlier). |

||

* Rachel Hall, ''[http://www.sju.edu/~rhall/Multi/rhythm2.pdf Hemachandra's application to Sanskrit poetry]'', (undated; 2005 or earlier). |

* Rachel Hall, ''[http://www.sju.edu/~rhall/Multi/rhythm2.pdf Hemachandra's application to Sanskrit poetry]'', (undated; 2005 or earlier). |

||

* Jean-claude Perez, ''[http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/freeabs_all.jsp?tp=&arnumber=137678&isnumber=3745 on links between Fractals and Fibonacci numbers]'', (1990) |

|||

* Alex Vinokur, ''[http://semillon.wpi.edu/~aofa/AofA/msg00012.html Computing Fibonacci numbers on a Turing Machine]'', (2003). |

* Alex Vinokur, ''[http://semillon.wpi.edu/~aofa/AofA/msg00012.html Computing Fibonacci numbers on a Turing Machine]'', (2003). |

||

* (no author given), ''[http://www.goldenmeangauge.co.uk/fibonacci.htm Fibonacci Numbers Information]'', (undated, 2005 or earlier). |

* (no author given), ''[http://www.goldenmeangauge.co.uk/fibonacci.htm Fibonacci Numbers Information]'', (undated, 2005 or earlier). |

||

Revision as of 11:16, 11 September 2008

In mathematics, the Fibonacci numbers are a sequence of numbers named after Leonardo of Pisa, known as Fibonacci. Fibonacci's 1202 book Liber Abaci introduced the sequence to Western European mathematics, although the sequence had been previously described in Indian mathematics.[2][3]

The first number of the sequence is 0, the second number is 1, and each subsequent number is equal to the sum of the previous two numbers of the sequence itself, yielding the sequence 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, etc. In mathematical terms, it is defined by the following recurrence relation:

That is, after two starting values, each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers. The first Fibonacci numbers (sequence A000045 in the OEIS), also denoted as Fn, for n = 0, 1, 2, … ,20 are:[4][5]

F0 F1 F2 F3 F4 F5 F6 F7 F8 F9 F10 F11 F12 F13 F14 F15 F16 F17 F18 F19 F20 0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377 610 987 1597 2584 4181 6765

Every 3rd number of the sequence is even and more generally, every kth number of the sequence is a multiple of Fk.

The sequence extended to negative index n satisfies Fn = Fn−1 + Fn−2 for all integers n, and F−n = (−1)n+1Fn:

.., −8, 5, −3, 2, −1, 1, followed by the sequence above.

Origins

The Fibonacci numbers first appeared, under the name mātrāmeru (mountain of cadence), in the work of the Sanskrit grammarian Pingala (Chandah-shāstra, the Art of Prosody, 450 or 200 BC). Prosody was important in ancient Indian ritual because of an emphasis on the purity of utterance. The Indian mathematician Virahanka (6th century AD) showed how the Fibonacci sequence arose in the analysis of metres with long and short syllables. Subsequently, the Jain philosopher Hemachandra (c.1150) composed a well-known text on these. A commentary on Virahanka's work by Gopāla in the 12th century also revisits the problem in some detail.

Sanskrit vowel sounds can be long (L) or short (S), and Virahanka's analysis, which came to be known as mātrā-vṛtta, wishes to compute how many metres (mātrās) of a given overall length can be composed of these syllables. If the long syllable is twice as long as the short, the solutions are:

- 1 mora: S (1 pattern)

- 2 morae: SS; L (2)

- 3 morae: SSS, SL; LS (3)

- 4 morae: SSSS, SSL, SLS; LSS, LL (5)

- 5 morae: SSSSS, SSSL, SSLS, SLSS, SLL; LSSS, LSL, LLS (8)

- 6 morae: SSSSSS, SSSSL, SSSLS, SSLSS, SLSSS, LSSSS, SSLL, SLSL, SLLS, LSSL, LSLS, LLSS, LLL (13)

- 7 morae: SSSSSSS, SSSSSL, SSSSLS, SSSLSS, SSLSSS, SLSSSS, LSSSSS, SSSLL, SSLSL, SLSSL, LSSSL, SSLLS, SLSLS, LSSLS, SLLSS, LSLSS, LLSSS, SLLL, LSLL, LLSL, LLLS (21)

A pattern of length n can be formed by adding S to a pattern of length n − 1, or L to a pattern of length n − 2; and the prosodicists showed that the number of patterns of length n is the sum of the two previous numbers in the sequence. Donald Knuth reviews this work in The Art of Computer Programming as equivalent formulations of the bin packing problem for items of lengths 1 and 2.

In the West, the sequence was first studied by Leonardo of Pisa, known as Fibonacci, in his Liber Abaci (1202)[6]. He considers the growth of an idealised (biologically unrealistic) rabbit population, assuming that:

- In the "zeroth" month, there is one pair of rabbits (additional pairs of rabbits = 0)

- In the first month, the first pair begets another pair (additional pairs of rabbits = 1)

- In the second month, both pairs of rabbits have another pair, and the first pair dies (additional pairs of rabbits = 1)

- In the third month, the second pair and the new two pairs have a total of three new pairs, and the older second pair dies. (additional pairs of rabbits = 2)

The laws of this are that each pair of rabbits has 2 pairs in its lifetime, and dies.

Let the population at month n be F(n). At this time, only rabbits who were alive at month n − 2 are fertile and produce offspring, so F(n − 2) pairs are added to the current population of F(n − 1). Thus the total is F(n) = F(n − 1) + F(n − 2).[7]

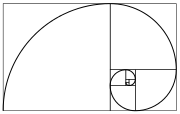

Relation to the Golden Ratio

Closed form expression

Like every sequence defined by linear recurrence, the Fibonacci numbers have a closed-form solution. It has become known as Binet's formula, even though it was already known by Abraham de Moivre:

- where is the golden ratio

- (sequence A001622 in the OEIS)

(note, that , as can be seen from the defining equation below).

The Fibonacci recursion

is similar to the defining equation of the golden ratio in the form

which is also known as the generating polynomial of the recursion.

Proof by induction

Any root of the equation above satisfies and multiplying by shows:

By definition is a root of the equation, and the other root is . Therefore:

and

Both and are geometric series (for n = 1, 2, 3, ...) that satisfy the Fibonacci recursion. The first series grows exponentially; the second exponentially tends to zero, with alternating signs. Because the Fibonacci recursion is linear, any linear combination of these two series will also satisfy the recursion. These linear combinations form a two-dimensional linear vector space; the original Fibonacci sequence can be found in this space.

Linear combinations of series and , with coefficients a and b, can be defined by

- for any real

All thus-defined series satisfy the Fibonacci recursion

Requiring that and yields and , resulting in the formula of Binet we started with. It has been shown that this formula satisfies the Fibonacci recursion. Furthermore, an explicit check can be made:

and

establishing the base cases of the induction, proving that

- for all

Therefore, for any two starting values, a combination can be found such that the function is the exact closed formula for the series.

Computation by rounding

Since for all , the number is the closest integer to Therefore it can be found by rounding, or in terms of the floor function:

Limit of consecutive quotients

Johannes Kepler observed that the ratio of consecutive Fibonacci numbers converges. He wrote that "as 5 is to 8 so is 8 to 13, practically, and as 8 is to 13, so is 13 to 21 almost”, and concluded that the limit approaches the golden ratio .[8]

This convergence does not depend on the starting values chosen, excluding 0, 0.

Proof:

It follows from the explicit formula that for any real

because and thus

Decomposition of powers of the golden ratio

Since the golden ratio satisfies the equation

this expression can be used to decompose higher powers as a linear function of lower powers, which in turn can be decomposed all the way down to a linear combination of and 1. The resulting recurrence relationships yield Fibonacci numbers as the linear coefficients, thus closing the loop:

This expression is also true for if the Fibonacci sequence is extended to negative integers using the Fibonacci rule

Matrix form

A 2-dimensional system of linear difference equations that describes the Fibonacci sequence is

or

The eigenvalues of the matrix A are and , and the elements of the eigenvectors of A, and , are in the ratios and

This matrix has a determinant of −1, and thus it is a 2×2 unimodular matrix. This property can be understood in terms of the continued fraction representation for the golden ratio:

The Fibonacci numbers occur as the ratio of successive convergents of the continued fraction for , and the matrix formed from successive convergents of any continued fraction has a determinant of +1 or −1.

The matrix representation gives the following closed expression for the Fibonacci numbers:

Taking the determinant of both sides of this equation yields Cassini's identity

Additionally, since for any square matrix , the following identities can be derived:

In particular, with ,

For another way to derive the formulas see the "EWD note" by Dijkstra[9].

Recognizing Fibonacci numbers

The question may arise whether a positive integer is a Fibonacci number. Since is the closest integer to , the most straightforward, brute-force test is the identity

which is true if and only if is a Fibonacci number.

Alternatively, a positive integer is a Fibonacci number if and only if one of or is a perfect square.[10]

A slightly more sophisticated test uses the fact that the convergents of the continued fraction representation of are ratios of successive Fibonacci numbers, that is the inequality

(with coprime positive integers , ) is true if and only if and are successive Fibonacci numbers. From this one derives the criterion that is a Fibonacci number if and only if the closed interval

contains a positive integer.[11]

Identities

Most identities involving Fibonacci numbers draw from combinatorial arguments. F(n) can be interpreted as the number of ways summing 1's and 2's to n − 1, with the convention that F(0) = 0, meaning no sum will add up to −1, and that F(1) = 1, meaning the empty sum will "add up" to 0. Here the order of the summands matters. For example, 1 + 2 and 2 + 1 are considered two different sums and are counted twice.

First Identity

- The nth Fibonacci number is the sum of the previous two Fibonacci numbers.

Proof

We must establish that the sequence of numbers defined by the combinatorial interpretation above satisfy the same recurrence relation as the Fibonacci numbers (and so are indeed identical to the Fibonacci numbers).

The set of F(n+1) ways of making ordered sums of 1's and 2's that sum to n may be divided into two non-overlapping sets. The first set contains those sums whose first summand is 1; the remainder sums to n−1, so there are F(n) sums in the first set. The second set contains those sums whose first summand is 2; the remainder sums to n−2, so there are F(n−1) sums in the second set. The first summand can only be 1 or 2, so these two sets exhaust the original set. Thus F(n+1) = F(n) + F(n−1).

Second Identity

- The sum of the first n Fibonacci numbers is the (n+2)nd Fibonacci number minus 1.

Proof

We count the number of ways summing 1's and 2's to n + 1 such that at least one of the summands is 2.

As before, there are F(n + 2) ways summing 1's and 2's to n + 1 when n ≥ 0. Since there is only one sum of n + 1 that does not use any 2, namely 1 + … + 1 (n + 1 terms), we subtract 1 from F(n + 2).

Equivalently, we can consider the first occurrence of 2 as a summand. If, in a sum, the first summand is 2, then there are F(n) ways to the complete the counting for n − 1. If the second summand is 2 but the first is 1, then there are F(n − 1) ways to complete the counting for n − 2. Proceed in this fashion. Eventually we consider the (n + 1)th summand. If it is 2 but all of the previous n summands are 1's, then there are F(0) ways to complete the counting for 0. If a sum contains 2 as a summand, the first occurrence of such summand must take place in between the first and (n + 1)th position. Thus F(n) + F(n − 1) + … + F(0) gives the desired counting.

Third Identity

This identity has slightly different forms for , depending on whether k is odd or even.

- The sum of the first n-1 Fibonacci numbers, , such that j is odd is the (2n)th Fibonacci number.

- The sum of the first n Fibonacci numbers, , such that j is even is the (2n+1)th Fibonacci number minus 1.

Proofs

By induction for :

A basis case for this could be .

By induction for :

A basis case for this could be .

Fourth Identity

Proof

This identity can be established in two stages. First, we count the number of ways summing 1s and 2s to −1, 0, …, or n + 1 such that at least one of the summands is 2.

By our second identity, there are F(n + 2) − 1 ways summing to n + 1; F(n + 1) − 1 ways summing to n; …; and, eventually, F(2) − 1 way summing to 1. As F(1) − 1 = F(0) = 0, we can add up all n + 1 sums and apply the second identity again to obtain

- [F(n + 2) − 1] + [F(n + 1) − 1] + … + [F(2) − 1]

- = [F(n + 2) − 1] + [F(n + 1) − 1] + … + [F(2) − 1] + [F(1) − 1] + F(0)

- = F(n + 2) + [F(n + 1) + … + F(1) + F(0)] − (n + 2)

- = F(n + 2) + [F(n + 3) − 1] − (n + 2)

- = F(n + 2) + F(n + 3) − (n + 3).

On the other hand, we observe from the second identity that there are

- F(0) + F(1) + … + F(n − 1) + F(n) ways summing to n + 1;

- F(0) + F(1) + … + F(n − 1) ways summing to n;

……

- F(0) way summing to −1.

Adding up all n + 1 sums, we see that there are

- (n + 1) F(0) + n F(1) + … + F(n) ways summing to −1, 0, …, or n + 1.

Since the two methods of counting refer to the same number, we have

- (n + 1) F(0) + n F(1) + … + F(n) = F(n + 2) + F(n + 3) − (n + 3)

Finally, we complete the proof by subtracting the above identity from n + 1 times the second identity.

Fifth Identity

- The sum of the first n Fibonacci numbers squared is the product of the nth and (n+1)th Fibonacci numbers.

Identity for doubling n

Another Identity

Another identity useful for calculating Fn for large values of n is

from which other identities for specific values of k, n, and c can be derived below, including

for all integers n and k. Dijkstra[9] points out that doubling identities of this type can be used to calculate Fn using O(log n) arithmetic operations. Notice that, with the definition of Fibonacci numbers with negative n given in the introduction, this formula reduces to the double n formula when k = 0.

(From practical standpoint it should be noticed that the calculation involves manipulation of numbers with length (number of digits) . Thus the actual performance depends mainly upon efficiency of the implemented long multiplication, and usually is or .)

Other identities

Other identities include relationships to the Lucas numbers, which have the same recursive properties but start with L0=2 and L1=1. These properties include F2n=FnLn.

There are also scaling identities, which take you from Fn and Fn+1 to a variety of things of the form Fan+b; for instance

by Cassini's identity.

These can be found experimentally using lattice reduction, and are useful in setting up the special number field sieve to factorize a Fibonacci number. Such relations exist in a very general sense for numbers defined by recurrence relations, see the section on multiplication formulae under Perrin numbers for details.

Power series

The generating function of the Fibonacci sequence is the power series

This series has a simple and interesting closed-form solution for

This solution can be proven by using the Fibonacci recurrence to expand each coefficient in the infinite sum defining :

Solving the equation for results in the closed form solution.

In particular, math puzzle-books note the curious value , or more generally

for all integers .

Conversely,

Reciprocal sums

Infinite sums over reciprocal Fibonacci numbers can sometimes be evaluated in terms of theta functions. For example, we can write the sum of every odd-indexed reciprocal Fibonacci number as

and the sum of squared reciprocal Fibonacci numbers as

If we add 1 to each Fibonacci number in the first sum, there is also the closed form

and there is a nice nested sum of squared Fibonacci numbers giving the reciprocal of the golden ratio,

Results such as these make it plausible that a closed formula for the plain sum of reciprocal Fibonacci numbers could be found, but none is yet known. Despite that, the reciprocal Fibonacci constant

has been proved irrational by Richard André-Jeannin.

Primes and divisibility

A Fibonacci prime is a Fibonacci number that is prime (sequence A005478 in the OEIS). The first few are:

- 2, 3, 5, 13, 89, 233, 1597, 28657, 514229, …

Fibonacci primes with thousands of digits have been found, but it is not known whether there are infinitely many. They must all have a prime index, except F4 = 3. There are arbitrarily long runs of composite numbers and therefore also of composite Fibonacci numbers.

With the exceptions of 1, 8 and 144 (F0 = F1, F6 and F12) every Fibonacci number has a prime factor that is not a factor of any smaller Fibonacci number (Carmichael's theorem).[14] 0, 1, and 144 are also the only square Fibonacci numbers.[15]

No Fibonacci number greater than F6 = 8 is one greater or one less than a prime number.[16]

Any three consecutive Fibonacci numbers, taken two at a time, are relatively prime: that is,

- gcd(Fn, Fn+1) = gcd(Fn, Fn+2) = 1.

More generally,

Odd divisors

If n is odd all the odd divisors of Fn are ≡ 1 (mod 4).[19][20]

This is equivalent to saying that for odd n all the odd prime factors of Fn are ≡ 1 (mod 4).

For example,

F1 = 1, F3 = 2, F5 = 5, F7 = 13, F9 = 34 = 2×17, F11 = 89, F13 = 233, F15 = 610 = 2×5×61

Fibonacci and Legendre

There are some interesting formulas connecting the Fibonacci numbers and the Legendre symbol

If p is a prime number then[21][22]

For example,

Also, if p ≠ 5 is an odd prime number then: [23]

Examples of all the cases:

Divisibility by 11

For example, let n = 1:

F1+F2+...+F10 = 1 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 5 + 8 + 13 + 21 + 34 + 55 = 143 = 11×13

n = 2:

F2+F3+...+F11 = 1 + 2 + 3 + 5 + 8 + 13 + 21 + 34 + 55 + 89 = 231 = 11×21

n = 3:

F3+F4+...+F12 = 2 + 3 + 5 + 8 + 13 + 21 + 34 + 55 + 89 + 144= 374 = 11×34

In fact, the identity is true for all integers n, not just positive ones:

n = 0:

F0+F1+...+F9 = 0 + 1 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 5 + 8 + 13 + 21 + 34 = 88 = 11×8

n = −1:

F−1+F0+...+F8 = 1 + 0 + 1 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 5 + 8 + 13 + 21 = 55 = 11×5

n = −2:

F−2+F−1+F0+...+F7 = −1 + 1 + 0 + 1 + 1 + 2 + 3 + 5 + 8 + 13 = 33 = 11×3

Right triangles

Starting with 5, every second Fibonacci number is the length of the hypotenuse of a right triangle with integer sides, or in other words, the largest number in a Pythagorean triple. The length of the longer leg of this triangle is equal to the sum of the three sides of the preceding triangle in this series of triangles, and the shorter leg is equal to the difference between the preceding bypassed Fibonacci number and the shorter leg of the preceding triangle.

The first triangle in this series has sides of length 5, 4, and 3. Skipping 8, the next triangle has sides of length 13, 12 (5 + 4 + 3), and 5 (8 − 3). Skipping 21, the next triangle has sides of length 34, 30 (13 + 12 + 5), and 16 (21 − 5). This series continues indefinitely. The triangle sides a, b, c can be calculated directly:

These formulas satisfy for all n, but they only represent triangle sides when .

Any four consecutive Fibonacci numbers Fn, Fn+1, Fn+2 and Fn+3 can also be used to generate a Pythagorean triple in a different way:

Example 1: let the Fibonacci numbers be 1, 2, 3 and 5. Then:

Example 2: let the Fibonacci numbers be 8, 13, 21 and 34. Then:

Magnitude of Fibonacci numbers

Since is asymptotic to , the number of digits in the base b representation of is asymptotic to .

For every integer d greater than 1 there are either 4 or 5 Fibonacci numbers with d digits in base 10.

Applications

The Fibonacci numbers are important in the run-time analysis of Euclid's algorithm to determine the greatest common divisor of two integers: the worst case input for this algorithm is a pair of consecutive Fibonacci numbers.

Yuri Matiyasevich was able to show that the Fibonacci numbers can be defined by a Diophantine equation, which led to his original solution of Hilbert's tenth problem.

The Fibonacci numbers occur in the sums of "shallow" diagonals in Pascal's triangle and Lozanić's triangle (see "Binomial coefficient"). (They occur more obviously in Hosoya's triangle).

Every positive integer can be written in a unique way as the sum of one or more distinct Fibonacci numbers in such a way that the sum does not include any two consecutive Fibonacci numbers. This is known as Zeckendorf's theorem, and a sum of Fibonacci numbers that satisfies these conditions is called a Zeckendorf representation.

The Fibonacci numbers and principle is also used in the financial markets. It is used in trading algorithms, applications and strategies. Some typical forms include: the Fibonacci fan, Fibonacci Arc, Fibonacci Retracement and the Fibonacci Time Extension.

Fibonacci numbers are used by some pseudorandom number generators.

Fibonacci numbers are used in a polyphase version of the merge sort algorithm in which an unsorted list is divided into two lists whose lengths correspond to sequential Fibonacci numbers - by dividing the list so that the two parts have lengths in the approximate proportion φ. A tape-drive implementation of the polyphase merge sort was described in The Art of Computer Programming.

Fibonacci numbers arise in the analysis of the Fibonacci heap data structure.

A one-dimensional optimization method, called the Fibonacci search technique, uses Fibonacci numbers.[24]

The Fibonacci number series is used for optional lossy compression in the IFF 8SVX audio file format used on Amiga computers. The number series compands the original audio wave similar to logarithmic methods e.g. µ-law.[25][26]

In music, Fibonacci numbers are sometimes used to determine tunings, and, as in visual art, to determine the length or size of content or formal elements. It is commonly thought that the first movement of Béla Bartók's Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta was structured using Fibonacci numbers.

Since the conversion factor 1.609344 for miles to kilometers is close to the golden ratio (denoted φ), the decomposition of distance in miles into a sum of Fibonacci numbers becomes nearly the kilometer sum when the Fibonacci numbers are replaced by their successors. This method amounts to a radix 2 number register in golden ratio base φ being shifted. To convert from kilometers to miles, shift the register down the Fibonacci sequence instead.[27][28][29]

Fibonacci numbers in nature

Fibonacci sequences appear in biological settings,[30] in two consecutive Fibonacci numbers, such as branching in trees, arrangement of leaves on a stem, the fruitlets of a pineapple,[31] the flowering of artichoke, an uncurling fern and the arrangement of a pine cone.[32] In addition, numerous poorly substantiated claims of Fibonacci numbers or golden sections in nature are found in popular sources, e.g. relating to the breeding of rabbits, the spirals of shells, and the curve of waves[citation needed]. The Fibonacci numbers are also found in the family tree of honeybees. [33]

Przemyslaw Prusinkiewicz advanced the idea that real instances can be in part understood as the expression of certain algebraic constraints on free groups, specifically as certain Lindenmayer grammars.[34]

A model for the pattern of florets in the head of a sunflower was proposed by H. Vogel in 1979.[35] This has the form

- ,

where n is the index number of the floret and c is a constant scaling factor; the florets thus lie on Fermat's spiral. The divergence angle, approximately 137.51°, is the golden angle, dividing the circle in the golden ratio. Because this ratio is irrational, no floret has a neighbor at exactly the same angle from the center, so the florets pack efficiently. Because the rational approximations to the golden ratio are of the form F(j):F(j+1), the nearest neighbors of floret number n are those at n±F(j) for some index j which depends on r, the distance from the center. It is often said that sunflowers and similar arrangements have 55 spirals in one direction and 89 in the other (or some other pair of adjacent Fibonacci numbers), but this is true only of one range of radii, typically the outermost and thus most conspicuous.[36]

Popular culture

Generalizations

The Fibonacci sequence has been generalized in many ways. These include:

- Generalizing the index to negative integers to produce the Negafibonacci numbers.

- Generalizing the index to real numbers using a modification of Binet's formula. [37]

- Starting with other integers. Lucas numbers have L1 = 1, L2 = 3, and Ln = Ln−1 + Ln−2. Primefree sequences use the Fibonacci recursion with other starting points in order to generate sequences in which all numbers are composite.

- Letting a number be a linear function (other than the sum) of the 2 preceding numbers. The Pell numbers have Pn = 2Pn – 1 + Pn – 2.

- Not adding the immediately preceding numbers. The Padovan sequence and Perrin numbers have P(n) = P(n – 2) + P(n – 3).

- Generating the next number by adding 3 numbers (tribonacci numbers), 4 numbers (tetranacci numbers), or more.

- Adding other objects than integers, for example functions or strings -- one essential example is Fibonacci polynomials.

Numbers properties

Periodicity mod n: Pisano periods

It is easily seen that if the members of the Fibonacci sequence are taken mod n, the resulting sequence must be periodic with period at most . The lengths of the periods for various n form the so-called Pisano periods (sequence A001175 in the OEIS). Determining the Pisano periods in general is an open problem,[citation needed] although for any particular n it can be solved as an instance of cycle detection.

The bee ancestry code

Fibonacci numbers also appear in the description of the reproduction of a population of idealized bees, according to the following rules:

- If an egg is laid by an unmated female, it hatches a male.

- If, however, an egg was fertilized by a male, it hatches a female.

Thus, a male bee will always have one parent, and a female bee will have two.

If one traces the ancestry of any male bee (1 bee), he has 1 female parent (1 bee). This female had 2 parents, a male and a female (2 bees). The female had two parents, a male and a female, and the male had one female (3 bees). Those two females each had two parents, and the male had one (5 bees). This sequence of numbers of parents is the Fibonacci sequence.[38]

This is an idealization that does not describe actual bee ancestries. In reality, some ancestors of a particular bee will always be sisters or brothers, thus breaking the lineage of distinct parents.

See also

- Logarithmic spiral

- Fibonacci number program at Wikibooks

- The Fibonacci Association

- Fibonacci Quarterly — an academic journal devoted to the study of Fibonacci numbers

- Negafibonacci numbers

- Lucas number

References

- ^ http://www.quipus.it/english/Andean%20Calculators.pdf

- ^ Parmanand Singh. "Acharya Hemachandra and the (so called) Fibonacci Numbers". Math. Ed. Siwan, 20(1):28-30, 1986. ISSN 0047-6269]

- ^ Parmanand Singh,"The So-called Fibonacci numbers in ancient and medieval India." Historia Mathematica 12(3), 229–44, 1985.

- ^ By modern convention, the sequence begins with F0=0. The Liber Abaci began the sequence with F1 = 1, omitting the initial 0, and the sequence is still written this way by some.

- ^ The website [1] has the first 300 Fn factored into primes and links to more extensive tables.

- ^ Sigler, Laurence E. (trans.) (2002). Fibonacci's Liber Abaci. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-95419-8. Chapter II.12, pp. 404–405.

- ^ Knott, Ron. "Fibonacci's Rabbits". University of Surrey School of Electronics and Physical Sciences.

- ^ Kepler, Johannes (1966). A New Year Gift: On Hexagonal Snow. Oxford University Press. p. 92. ISBN 0198581203. Strena seu de Nive Sexangula (1611)

- ^ a b E. W. Dijkstra (1978). In honour of Fibonacci. Report EWD654

- ^ Posamentier, Alfred (2007). The (Fabulous) FIBONACCI Numbers. Prometheus Books. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-59102-475-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ M. Möbius, Wie erkennt man eine Fibonacci Zahl?, Math. Semesterber. (1998) 45; 243–246

- ^ Vorobiev, Nikolaĭ Nikolaevich (2002). "Chapter 1". Fibonacci Numbers. Birkhäuser. pp. pp. 5–6. ISBN 3-7643-6135-2.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Fibonacci Number - from Wolfram MathWorld

- ^ Ron Knott, "The Fibonacci numbers".

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Ross Honsberger Mathematical Gems III (AMS Dolciani Mathematcal Expositions No. 9), 1985, ISBN 0-88385-318-3, p. 133.

- ^ Paulo Ribenboim, My Numbers, My Friends, Springer-Verlag 2000

- ^ Su, Francis E., et al. "Fibonacci GCD's, please.", Mudd Math Fun Facts.

- ^ Lemmermeyer, ex. 2.27 p. 73

- ^ The website [2] has the first 300 Fibonacci numbers factored into primes.

- ^ Paulo Ribenboim (1996), The New Book of Prime Number Records, New York: Springer, ISBN 0-387-94457-5, p. 64

- ^ Franz Lemmermeyer (2000), Reciprocity Laws, New York: Springer, ISBN 3-540-66957-4, ex 2.25-2.28, pp. 73-74

- ^ Lemmermeyer, ex. 2.38, pp. 73-74

- ^ M. Avriel and D.J. Wilde (1966). "Optimality of the Symmetric Fibonacci Search Technique". Fibonacci Quarterly (3): 265–269.

- ^ Amiga ROM Kernel Reference Manual, Addison-Wesley 1991

- ^ IFF - MultimediaWiki

- ^ An Application of the Fibonacci Number Representation

- ^ A Practical Use of the Sequence

- ^ Zeckendorf representation

- ^ S. Douady and Y. Couder (1996). "Phyllotaxis as a Dynamical Self Organizing Process" (PDF). Journal of Theoretical Biology. 178 (178): 255–274. doi:10.1006/jtbi.1996.0026.

- ^ Jones, Judy (2006). "Science". An Incomplete Education. Ballantine Books. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-7394-7582-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ A. Brousseau (1969). "Fibonacci Statistics in Conifers". Fibonacci Quarterly (7): 525–532.

- ^ Computer Science for Fun - cs4fn: Marks for the da Vinci Code: B

- ^ Prusinkiewicz, Przemyslaw (1989). Lindenmayer Systems, Fractals, and Plants (Lecture Notes in Biomathematics). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-97092-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Vogel, H (1979), "A better way to construct the sunflower head", Mathematical Biosciences, 44 (44): 179–189, doi:10.1016/0025-5564(79)90080-4

- ^ Prusinkiewicz, Przemyslaw (1990). [[The Algorithmic Beauty of Plants]]. Springer-Verlag. pp. 101–107. ISBN 978-0387972978.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pravin Chandra and Eric W. Weisstein. "Fibonacci Number". MathWorld.

- ^ The Fibonacci Numbers and the Ancestry of Bees

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. |

- Ron Knott, The Golden Section: Phi, (2005).

- Ron Knott, Representations of Integers using Fibonacci numbers, (2004).

- wallstreetcosmos.com, Fibonacci numbers and stock market analysis, (2008).

- Juanita Lofthouse Fibonacci numbers and Red Blood Cell Dynamics, .

- Bob Johnson, Fibonacci resources, (2004)

- Donald E. Simanek, Fibonacci Flim-Flam, (undated, 2005 or earlier).

- Rachel Hall, Hemachandra's application to Sanskrit poetry, (undated; 2005 or earlier).

- Alex Vinokur, Computing Fibonacci numbers on a Turing Machine, (2003).

- (no author given), Fibonacci Numbers Information, (undated, 2005 or earlier).

- Fibonacci Numbers and the Golden Section – Ron Knott's Surrey University multimedia web site on the Fibonacci numbers, the Golden section and the Golden string.

- The Fibonacci Association incorporated in 1963, focuses on Fibonacci numbers and related mathematics, emphasizing new results, research proposals, challenging problems, and new proofs of old ideas.

- Dawson Merrill's Fib-Phi link page.

- Fibonacci primes

- Periods of Fibonacci Sequences Mod m at MathPages

- The One Millionth Fibonacci Number

- The Ten Millionth Fibonacci Number

- An Expanded Fibonacci Series Generator

- Manolis Lourakis, Fibonaccian search in C

- Scientists find clues to the formation of Fibonacci spirals in nature

- Fibonacci Numbers at Convergence

- Online Fibonacci calculator

![{\displaystyle {\bigg [}\varphi z-{\frac {1}{z}},\varphi z+{\frac {1}{z}}{\bigg ]}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/14edda62f581eb4023de98ff582af9a5cf01aae5)