Situated cognition: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tag: blanking |

|||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Recent perspectives of situated cognition have focused on and drawn from the concept of identity formation (Lave & Wenger, 1991) as people negotiate meaning (Brown & Duguid, 2000; Clancy, 1994) through interactions within communities of practice. Situated cognition perspectives have been adopted in education (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989), instructional design (Young, 2004), online communities and artificial intelligence (see Brooks, Clancey). Grounded Cognition, concerned with the role of simulations and embodiment in cognition, encompasses Cognitive Linguistics, Situated Action, Simulation and Social Simulation theories. Recent research has contributed to the understanding of embodied language, memory, and the representation of knowledge (Barsalou, 2007). |

Recent perspectives of situated cognition have focused on and drawn from the concept of identity formation (Lave & Wenger, 1991) as people negotiate meaning (Brown & Duguid, 2000; Clancy, 1994) through interactions within communities of practice. Situated cognition perspectives have been adopted in education (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989), instructional design (Young, 2004), online communities and artificial intelligence (see Brooks, Clancey). Grounded Cognition, concerned with the role of simulations and embodiment in cognition, encompasses Cognitive Linguistics, Situated Action, Simulation and Social Simulation theories. Recent research has contributed to the understanding of embodied language, memory, and the representation of knowledge (Barsalou, 2007). |

||

==Glossary== |

|||

==Situativity contrasted with schema and information processing approaches== |

|||

{{limited}} |

{{limited}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|||

! Term |

|||

! Definition |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|- |

||

|affordance |

|||

! '''Key Phenomena''' |

|||

|infinite properties in the environment that present possibilities for action and are available for an agent to perceive directly and act upon |

|||

! Situated Cognition |

|||

! Information Processing |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|attention and intention |

|||

! Intelligence |

|||

|Once an intention (goal) is adopted, the agent’s perception (attention) is attuned to the affordances of the environment. |

|||

| Intelligence can be defined as an increasingly sophisticated interaction with the world. This sophisticated behavior, that we call intelligence, is an emergent property of an interaction. The interaction gets smarter, more sophisticated, and more differentiated, as the agent and environment potentially evolve over time (Gibson 1979/1986; Greeno, 1994; Young Kulikowich, & Barab, 1997). |

|||

| Jeanne Ormrod (2004) highlighted the controversy among psychologists on the issue of intelligence when she stated, "some have an entity view: They believe that intelligence is a 'thing' that is fairly permanent and unchangeable. Others have an incremental view: They believe that intelligence can and does improve with effort and practice" (Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Weiner, 1994). |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|attunement |

|||

! Motivation |

|||

| |

|||

| Motivation is described in terms of intentional dynamics. "Intentions denote a mismatch between the presence of a goal-state attractor (a possible final condition) and the actual state of the environment (the initial condition)...As the goal-states are created or annihilated, the intersection set will shift" (Kugler, Shaw, Vicente & Kinsella-Shaw, 1991, p.425). The agent's immediate or future goals influence his intentions, and serve as a guide in his interaction with the world. "Successful goal-directed behavior is possible whenever goal-specific information, made available by the environment, can be matched by the control of action exercised by the organism. This dual information/control field that couples the organism and environment provides the lawful basis for intentional dynamics" (Kugler et al., 1991, p.427). |

|||

| "Most contemporary [cognitive] theorists describe human motivation as being a function of human cognition. For example, people set specific goals toward which they strive. They form expectations regarding likelihood of success in different activities. They construct interpretations of why certain consequences come their way, and they make predictions about the future consequences of their behavior" (Ormrod, 2004, p.440) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|community of practice |

|||

! Memory |

|||

|The concept of a **community of practice** (often abbreviated as CoP) refers to the process of social learning that occurs and shared sociocultural practices that emerge and evolve when people who have common goals interact as they strive towards those goals. |

|||

| Situated Cognition understands memory as an interaction with the world (perception). The agent can represent things in his head and problem-solve, but he does so in a situation that is meaningfully bounded, and that brings himself towards a specified goal (intention). Perception and action are co-determined by the effectivities and affordances, which act 'in the moment' together (Gibson 1979/1986; Greeno, 1994; Young Kulikowich, & Barab, 1997). Therefore, the agent directly perceives and interacts with the environment, determining what affordances can be picked up, based on his effectivities. |

|||

| "[[Memory]] is related to the ability to recall information that has previously been learned. In some instances, the word ''[[memory]]'' is used to refer to the process of retaining information for a period of time. In other instances, it is used to refer to a particular 'location' where learned information is kept (e.g. working memory and long-term memory)" (Ormrod, 2004, p.186). |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|detection of invariants |

|||

! Problem Solving & Transfer |

|||

|perception of what doesn't change across different situations |

|||

| Problems are ill-defined, context bound, and real-world. The relationship between the solver and the environment affords multiple and various solutions. Transfer is an act of creation; it is an "advantageous effect of learning in one situation upon learning in a later situation" (Greeno, 2006, p. 545). |

|||

|- |

|||

| Problems are typically discrete and general. Solutions are figured right or wrong. Success is defined by following an orderly process to produce and then re-produce a solution(s) across various domains.[http://www.mediafrontier.com/Article/PS/PS.htm] |

|||

|direct perception (pick up) |

|||

|describes the way an agent in an environment senses affordances without the need for computation or symbolic representation |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|effectivities |

|||

! How People Learn |

|||

|The agents ability to recognize and use affordances of the environment. |

|||

| Learning is a process of increasing differentiation, a tuning at attention to finer and finer distinctions (E.J. Gibson, 2000). [[John Dewey]] (1938) described education as an essentially "social process" through which a mature individual "surveys the capacities and needs" of learners and creates experiences for them to further develop. Quality of education (learning) is realized in the, "...degree in which individuals form a community group" (Dewey, 1938, p. 58). Contemporary definitions share similar beliefs about the social construction of learning for example, Driscoll (2004), "Fundamental to situated cognition theory is the assumption that learning involves social participation..." (p. 170). And, "...learning is an integral part of generative social practice in the lived-in world" (Lave & Wenger, 1991, p. 35). |

|||

| Learning is a process of accumulating facts and an increasingly sophisticated network of connections (semantic net) among those facts. "Processes occurring during the presentation of the learning material are known as 'encoding'. Learning occurs in three stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval which, "...involves recovering or extracting stored information from the memory system" (Eysenck & Keane, 2005, p. 189). |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|embodiment |

|||

! Implications for Classroom Teaching |

|||

|as an explanation of cognition emphasizes first that the body exists as part of the world. In a dynamic process, perception and action occurring through and because of the body being in the world, interact to allow for the processes of simulation and representation. |

|||

| In the classroom (or other formal learning environments) the application of a situated learning "...emphasizes aspects of problem spaces that emerge in activity, the interactive construction of understanding, and people's engagement in activities, including their contributions to group functions and their development of individual identities" (Greeno, 1998, p. 14). As such, the approach includes attendance to learners' sociocultural experience, prior experience, and the embodiment of cognitive activity. Examples include ''anchored instruction'' [http://www.edtech.vt.edu/edtech/id/models/anchored.html]using richly complex problems to situate and enliven students' learning across multiple content areas (e.g., Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt, 1990); ''knowledge building'' [http://www.knowledgeforum.com/Kforum/inAction.htm] which allows students to build extensive webs of understanding or [[cognitive map]]s alone or in collaborative groups ([[Bereiter]] & [[Scardamalia]], 2003); and ''cognitive apprenticeship''[http://www.edtech.vt.edu/edtech/id/models/cog.html] through which expert learners aka teachers (or more advanced peers) take thinking "outside the head" by speaking aloud strategies they use to tackle the task at hand (e.g. Reciprocal Teaching; Collins, Brown, and Newman, 1989). |

|||

| Robert Gagne's Nine Events of Instruction [http://www.e-learningguru.com/articles/art3_3.htm] is a model which defines instruction as, "A deliberately arranged set of external events designed to support internal learning processes" (Gagne, Wager, Golas, & Keller, 2005, p. 10). Learning is described as "staged based information processing" (Gagne et al, 2005, p.7). Other views of learning, brain-based learning for example, assert teachers must have an awareness of "how the brain learns" in order to create effective learning experiences (Hart, 1990). In the classroom, teachers focus on how to present information in ways to increase retention to include: getting students attention thereby accessing appropriate schema (prior knowledge), providing opportunities for practice (to increase retention in long-term memory), and conducting domain-specific assessments to determine whether students retained the information and the likelihood of transfer (Gagne et al, 2005). |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|legitimate peripheral participation |

|||

! Research Methodologies |

|||

|the initial stage(s) of a person's active membership in a community of practice to which he or she has access and the opportunity to become a full participant. |

|||

| The situative perspective is focused on interactive systems in which individuals interact with one another and physical and representational systems. Research takes place ''in situ'' and in real-world settings reflecting assumptions that knowledge is constructed within specific contexts which have specific situational affordances. [[Qualitative research|Qualitative methodologies]] (see [http://www.aqr.org.uk/ Association for Qualitative Research]) are the most prominently used by researchers including: phenomenological inquiry, grounded theory building, ethnography, case studies, participant-observation, participatory action research, and in-depth interviewing. Populations are typically made up of a single [[community of practice]] (e.g., Vai and Gola tailors' apprentices in Liberia, Lave, 1977). |

|||

| The cognitive perspective is focused on processes and structures operative at the level of individuals. Experimentation with human subjects takes place in laboratory settings (including classroom or other well-defined environments) with an intervention group (for example, the children who were exposed to "aggressive behavior" in the now infamous [[Bobo doll experiment]] of [[Albert Bandura]]) and a control group. Results on [[psychometric]] measures (e.g., the [[Stanford-Binet IQ test]]) are examined and used to predict future behavior or performance in the individual. "Today, the key feature common to all experiments is still to deliberately vary something as to discover what happens to something else later--to discover the effects of presumed causes" (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002, p. 3). |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|perceiving and acting cycle |

|||

! Mind-Body Connection ([[Embodiment]]) |

|||

|Gibson (1986) described a continuous perception-action cycle, which is dynamic and ongoing. Agents perceive and act with intentionality in the environment at all times. |

|||

| "The mind must be understood in the context of its relationship to a physical body that interacts with the world" (Wilson, 2002, p.625). Situated cognition acknowledges the existence of an agent/environment interaction, where the agent acts on information that is available. Therefore, direct perception keeps the agent in touch with the world, and perception and action interact directly ‘on the fly.’ |

|||

| The [[cognitivist]] viewpoint approached "the mind as an abstract information processor, whose connections to the outside world were of little theoretical importance" (Wilson, 2002, p.625). Perception and motor systems are merely peripheral input and output devices (Niedenthal, 2007; Wilson, 2002), which essentially implies that "sensory, motor, and affective systems are not required for thinking or language use" (Niedenthal, 2007, p.1003). |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! Models of Knowledge |

|||

| Situated cognition focuses on dynamic interactions as a model of knowledge. The ''Dynamics of Intentions'' involves goal-adoption. It is where the agent intentionally adopts a specific goal. There may be many levels of intentions (goals), but at the moment of vision, the agent has just one intention, and that intention will control his behavior until it is fulfilled (Kugler et al., 1991; Shaw, Kadar, Sim & Repperger, 1992; Young et al., 1997). Once a goal has been adopted, the agent proceeds into what is known as, ''Intentional Dynamics''. These are the dynamics that unfold when the agent has that one intention (goal). The agent is now beginning to perceive and act towards that goal (Gibson 1979/1986). It is a trajectory towards the achievement of a solution or goal, the process of tuning one’s perception (attention). Each intention is meaningfully bounded, where the dynamics of that intention inform the agent of whether or not he is getting closer to achieving his goal (Kugler et al, 1991; Shaw et al., 1992; Young, et al., 1997). This is the agent’s intentional dynamics, and continues on until he achieves his goal. |

|||

| [[Nature versus nurture]] is a long standing dichotomy which describes knowledge as either innate or experiential. Schema and information processing models depend heavily upon the premise that knowledge exists in the mind (stored figuratively in schemata and literally in the synapses of the brain) and is abstract and symbolic, therefore decontextualized (see Eysenck & Keane, 2005). A common metaphor for this type of knowledge is a computer, according to this view "people (and computers) process information sequentially in a number of steps or stages. Humans selectively input information from the environment, then allow for some of that information to be reflected on and acted on" (Wilson & Meyers, 2000, p. 63). |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

Revision as of 11:43, 1 May 2009

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Overview Situated cognition posits that knowing is inseparable from doing (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989; Greeno, 1989) by arguing that all knowledge is situated in activity bound to social, cultural and physical contexts (Greeno & Moore, 1993).

Under this assumption, which requires an ontological shift from empiricism, situativity theorists suggest a model of knowledge and learning that requires thinking on the fly rather than the dissemination of concrete domain knowledge. In essence, cognition cannot be separated from the context. Instead knowing exists, in situ, inseparable from context, activity, people, culture, and language. Therefore, learning is seen in terms of an individual's increasingly effective performance across situations rather than in terms of an accumulation of knowledge since what is known is co-determined by the agent and the context.

History

While situated cognition gained recognition in the field of educational psychology in the late twentieth century (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989), it shares many principles with older post-structural fields such as critical theory, (Frankfurt School, 1930; Freire, 1968) anthropology (Lave & Wenger, 1991), philosophy (Heidegger, 1968), critical discourse analysis (Fairclough, 1989), and socio-linguistic theories (Bhaktin, 1981) that rejected the notion of truly objective knowledge and the principles of Kantian empiricism.

Situated cognition umbrellas a variety of perspectives, from an anthropological study of human behavior within communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991) to the psychological study of the perception-action cycle (Gibson, 1986) and intentional dynamics (Shaw, Kadar, Sim & Reppenger, 1992). Early attempts to define situated cognition focused on contrasting the emerging theory with information processing theories dominant in cognitive psychology (Bredo, 1994).

Recent perspectives of situated cognition have focused on and drawn from the concept of identity formation (Lave & Wenger, 1991) as people negotiate meaning (Brown & Duguid, 2000; Clancy, 1994) through interactions within communities of practice. Situated cognition perspectives have been adopted in education (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989), instructional design (Young, 2004), online communities and artificial intelligence (see Brooks, Clancey). Grounded Cognition, concerned with the role of simulations and embodiment in cognition, encompasses Cognitive Linguistics, Situated Action, Simulation and Social Simulation theories. Recent research has contributed to the understanding of embodied language, memory, and the representation of knowledge (Barsalou, 2007).

Glossary

This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. |

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| affordance | infinite properties in the environment that present possibilities for action and are available for an agent to perceive directly and act upon |

| attention and intention | Once an intention (goal) is adopted, the agent’s perception (attention) is attuned to the affordances of the environment. |

| attunement | |

| community of practice | The concept of a **community of practice** (often abbreviated as CoP) refers to the process of social learning that occurs and shared sociocultural practices that emerge and evolve when people who have common goals interact as they strive towards those goals. |

| detection of invariants | perception of what doesn't change across different situations |

| direct perception (pick up) | describes the way an agent in an environment senses affordances without the need for computation or symbolic representation |

| effectivities | The agents ability to recognize and use affordances of the environment. |

| embodiment | as an explanation of cognition emphasizes first that the body exists as part of the world. In a dynamic process, perception and action occurring through and because of the body being in the world, interact to allow for the processes of simulation and representation. |

| legitimate peripheral participation | the initial stage(s) of a person's active membership in a community of practice to which he or she has access and the opportunity to become a full participant. |

| perceiving and acting cycle | Gibson (1986) described a continuous perception-action cycle, which is dynamic and ongoing. Agents perceive and act with intentionality in the environment at all times. |

Key principles

According to Lave and Wenger (1991) legitimate peripheral participation (LPP) provides a framework to describe how individuals ('newcomers') become part of a community of learners. Legitimate peripheral participation was central to Lave and Wenger's take on situated cognition (referred to as "situated activity") because it introduced socio-cultural and historical realizations of power and access to the way thinking and knowing are legitimated. They stated, "Hegemony over resources for learning and alienation from full participation are inherent in the shaping of the legitimacy and peripherality of participation in its historical realizations" (p. 42). Lave and Wenger's (1991) research on the phenomenon of apprenticeship in communities of practice not only provided a unit of analysis for locating an individual's multiple, changing levels and ways of participation, but also implied that all participants, through increased involvement, have access to, acquire, and use resources available to their particular community.

To illustrate the role of LPP in situated activity, Lave and Wenger (1991) examined five apprenticeship scenarios (Yucatec midwives, Vai and Gola tailors, naval quartermasters, meat cutters, and nondrinking alcoholics involved in AA). Their analysis of apprenticeship across five different communities of learners lead them to several conclusions about the situatedness of LPP and its relationship to successful learning. Key to newcomers' success included:

- access to all that community membership entails,

- involvement in productive activity,

- learning the discourse(s) of the community including "talking about and talking within a practice," (p. 109), and

- willingness of the community to capitalize on the inexperience of newcomers, "Insofar as this continual interaction of new perspectives is sanctioned, everyone's participation is legitimately peripheral in some respect. In other words, everyone can to some degree be considered a 'newcomer' to the future of a changing community" (Lave & Wenger, 1991, p. 117).

A method of teaching that involves one teacher and up to seven students. Both teacher and student take turns playing the role of teacher. Instruction includes "modeling and coaching students in four strategic skills: formulating questions based on the text, summarizing the text, making predictions about what will come next, and clarifying difficulties with the text" (Collins et al., 1989, p.460).

Collins, Brown, and Newman (1989) emphasized six critical features of a cognitive apprenticeship that included observation, coaching, scaffolding, modeling, fading, and reflection. Using these critical features, expert(s) guided students on their journey to acquire the cognitive and metacognitive processes and skills necessary to handle a variety of tasks, in a range of situations (Collins et al., 1989). One example of a successful cognitive apprenticeship was Reciprocal Teaching of reading.

Results from a pilot study on the effectiveness of Reciprocal Teaching found that reading comprehension test scores of poor readers increased from pre-test to post-test following a Reciprocal Teaching training session. Further investigation revealed that students retained the majority of the information learned over time; with test scores remaining relatively stable (Collins et al., 1989. The success of this reading intervention was attributed to five factors:

- students had the opportunity to form a new conceptual model of reading,

- students actively utilized expert reader skills and strategies,

- the teacher modeled expert reader strategies directly with the students,

- the teacher utilized successful scaffolding techniques, and

- the student played the dual role as producer and critic (Collins et al., 1989).

Affordances and effectivities

The perceptual psychologist J.J. Gibson introduced the idea of affordances as part of a relational account of perception (Gibson, 1977). Gibson argued that perception should not be considered solely as the encoding of environmental features into the perceivers mind, but as an element of an individual's interaction with their environment. Central to his proposal of an ecological psychology was the notion of affordances. Gibson proposed that in any interaction between an agent and the environment, inherent conditions or qualities of the environment allow the agent to perform certain actions with the environment (Greeno, 1994). He defined the term as properties in the environment that presented possibilities for action and were available for an agent to perceive directly and act upon (Gibson 1979/1986).

Gibson focused on the affordances of physical objects, such as doorknobs and chairs, and suggested that these affordances were directly perceived by an individual instead of mediated by mental representations such as mental models. It is important to note that Gibson's notion of direct perception as an unmediated process of noticing, perceiving, and encoding specific attributes from the environment, has long been challenged by proponents of a more category-based model of perception.

This focus on agent-situation interactions in ecological psychology was consistent with the situated cognition program of researchers such as James G. Greeno (1994, 1998), who appreciated Gibson's apparent rejection of the factoring assumptions underlying experimental psychology. The situated cognition perspective focused on "perception-action instead of memory and retrieval…A perceiving/acting agent is coupled with a developing/adapting environment and what matters is how the two interact" (Young, Kulikowich, & Barab, 1997, p.139). Greeno (1994:340) also suggests that affordances are "preconditions for activity," and that while they do not determine behavior, they increase the likelihood that a certain action or behavior will occur.

Shaw, Turvey, & Mace (as cited by Greeno, 1994) later introduced the term effectivities, the abilities of the agent that determined what the agent could do, and consequently, the interaction that could take place. Perception and action were co-determined by the effectivities and affordances, which acted 'in the moment' together (Gibson 1979/1986; Greeno, 1994; Young et al., 1997). Therefore, the agent directly perceived and interacted with the environment, determining what affordances could be picked up, based on his effectivities. This view is consistent with Norman's (1988) theory of "perceived affordances," which emphasizes the agent's perception of an object's utility as opposed to focusing on the object itself.

An interesting question is the relationship between affordances and mental representations as set forth in a more cognitivist perspective. While Greeno (1998) argues that attunements to affordances are superior to constructs such as schemata and mental models, Glenberg & Robertson (1999) suggest that affordances are the building blocks of mental models.

"Successful problem solving often occurs in groups and requires the social construction of knowledge" (Young & McNeese, 1995, p. 360). From the perspective of research in situated cognition, problem solving must be real-world (aka authentic) in its complexity, 'ill-defined,' and 'interactive' between the learner and the context (including other learners); making it a process through which "...perceiving and acting create meaning on the fly, rather than reading it back from something (representational or schematic) in the head" (Young & McNeese, 1995, p. 368). Formal schooling typically teaches 'problem solving' as a single skill with problems that are 'straight forward and bounded' (as math story problems, for example) with the belief students will be equip to 'transfer' those skills to 'everyday practice' like planning a family budget (Lave, 1988). To the contrary a situated cognitive approach to teaching problem solving would recognize that, "It is the relationship between the agent and the problem that is problem solving" (Young et al., 1997, p. 140), therefore would attend to the problem-solver's abilities (aka effectivities) and to the resources available in the environment (aka affordances).

Problem solving in the real-world of schooling takes place all of the time, like when the 7th grader figures out how little money he can spend on lunch (to not have his stomach grumbling all day) so he can catch the city bus after school (which takes 30 minutes each way), and spend what's left of his lunch money on video games and candy, and ultimately make it home before his parents at 6:30p.m. Yet curriculum designers and teachers insist on "teaching" kids problem solving by asking them to figure out how long its going to take the A Train to get to the Hometown Station and back. The problem with the latter approach is solvers and their problems need to be embedded in environments that "...afford the problem-solving actions that students would normally engage" (Young & McNeese, 1995, p. 371). For example, The Jasper Woodbury Problem Solving Series videodiscs [1] created by The Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt (1990, 1993, 1994) to examine potential relationship(s) between situated cognition and situated learning and "anchored instruction" (i.e., "situating instruction in the context of information-rich environments that encouraged students and teachers to pose and solve complex, realistic problems").

Anchored Instruction

Instructional design is the education of intention (dynamics of intentions) and attention (intentional dynamics). It is where educators provide opportunities necessary for students to create or adopt meaningful goals (intentions). Thus, one of the educator’s objectives can be to set a goal through the use of an anchor problem (Barab & Roth, 2006; Young et al., 1997).

“The major goal of anchored instruction is to overcome the inert knowledge problem. We attempt to do so by creating environments that permit sustained exploration by students and teachers and enable them to understand the kinds of problems and opportunities that experts in various areas encounter and the knowledge that these experts use as tools. We also attempt to help students experience the value of exploring the same setting from multiple perspectives” (The Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt, 1990, p.3). One example of anchored instruction is the Jasper series[2] (The Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt, 1990; Young et al., 1997; Young & McNeese, 1995). The Jasper series includes a variety of videodisc adventures focused on problem formulation and problem solving. Each videodisc uses a visual narrative to present an authentic, real-world problem. The objective is for students to adopt specific goals (intentions) after viewing the disc. These newly adopted goals will now guide students through the collaborative process of problem formulation and problem solving (see #Goals, Intentions, & Attention).

Goals, Intentions, & Attention

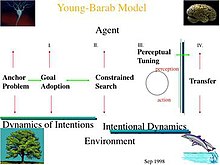

The Young-Barab Model (1998) pictured to the left, illustrates the dynamics of intentions and intentional dynamics involved in the agent’s interaction with his environment.

Dynamics of Intentions (Kugler et al., 1991; Shaw et al., 1992; Young et al., 1997): goal (intention) adoption. It is where the anchor problem is presented and the learner decides whether or not to adopt a particular goal. Once a goal is adopted, the learner proceeds towards the intentional dynamics. There are many levels of intentions, but at the moment of vision, the agent has just one intention, and that intention controls his behavior until it is fulfilled.

Intentional Dynamics (Kugler et al, 1991; Shaw et al., 1992; Young, et al., 1997): dynamics that unfold when the agent has only one intention (goal) and begins to act towards it, perceiving and acting (Gibson 1979/1986). It is a trajectory towards the achievement of a solution or goal, the process of tuning one’s perception (attention). Each intention is meaningfully bounded, where the dynamics of that intention inform the agent of whether or not he is getting closer to achieving his goal. If the agent is not getting closer to his goal, he will take corrective action, and then continue forward. This is the agent’s intentional dynamics, and continues on until he achieves his goal.

The traditional cognition approach assumes that perception and motor systems are merely peripheral input and output devices (Niedenthal, 2007; Wilson, 2002). However, embodied cognition posits that the mind and body interact ‘on the fly’ as a single entity. An example of embodied cognition is seen in the area of robotics, where movements are not based on internal representations, rather, they are based on the robot’s direct and immediate interaction with its environment (Wilson, 2002). Additionally, research has shown that embodied facial expressions influence judgments (Niedenthal, 2007), and arm movements are related to a person’s evaluation of a word or concept (Markman, & Brendl, 2005). In the later example, the individual would pull or push a lever towards his name at a faster rate for positive words, then for negative words. These results appeal to the embodied nature of situated cognition, where knowledge is the achievement of the whole body in its interaction with the world.

A variety of definitions for the term transfer appear in the literature and research on Situated Cognition.

- Jean Lave on transfer stated, "Learning transfer is assumed to be the central mechanism for bringing school-taught knowledge to bear in life after school" (Lave, 1988, p. 23).

- Greeno (1991 as cited in Greeno, 2006) described knowing using the metaphor of a neighborhood or workshop and stated, "The idea is that knowing a conceptual domain includes knowing what resources are available" (p. 543). Thus, he described transfer to "... therefore, involve having or taking authority to go beyond what one has been taught" (p. 546). Put simply, Greeno viewed transfer as an elegant, creative act that affords learners agency (via his concept of authoritative agency) and authorship (via his concept of accountable positioning) (2006).

- "In a certain sense every experience should do something to prepare a person for later experiences of a deeper and more expansive quality. That is the very meaning of growth, continuity, reconstruction of experience" (Dewey, 1938, p. 47).

- Young and McNeese (1995) stated that "analyzing transfer from an ecological perspective leads us to consider that detection of invariance across a 'generator set' of situations would be required for transfer across content areas" (p.384).

- "Learning in multiple contexts induces the abstraction of knowledge, so that students acquire knowledge in a dual form, both tied to the contexts of its uses and independent of any particular context. This unbinding of knowledge from a specific context fosters its transfer to new problems and new domains" (Collins et al., 1989, p.487).

- "We have come to believe that we should expect transfer only when there is a confluence of an individual's goals and objectives, their acquired abilities to act, and a set of affordances for action (specified by information) available within an environment. That is, whatever tuning of attention that leads to the initial occurrence of a behavior, transfer will occur when the agent has a similar goal, their abilities to act are similar, and the environment affords the goal-relevant action" (Young et al., 1997, p.147).

- "...Transfer is more likely to occur when learning contexts are framed as part of a larger ongoing intellectual conversation in which students are actively involved" (Engle, 2006, p.451).

Critiques of Situativity

Anderson, Reder, and Simon (1996) offered a critique of situated cognition in the journal Educational Researcher that initiated a well known series of rebuttals and counter-critiques. They specifically criticize the proponents of situated cognition theory for making four claims which they argue are not supported by the empirical evidence. These claims are (1) Action is grounded in the concrete situation in which it occurs, (2) Knowledge does not transfer between tasks, (3) Training by abstraction is of little use, and (4) Instruction needs to be done in complex, social environments. They argue that proponents of the situative perspective have over-stated their case, and ignores well-documented phenomena that are inconvenient to their claims. For example, while cognition is in part context-dependent, it can also be context-independent. Anderson, Reder, and Simon (1996:10) conclude their initial critique by stating that the situated movement has drawn "misguided implications for education" that must be forcefully disavowed by the cognitive science community.

Greeno responded the following year in the same journal by suggesting that Anderson, Reder, and Simon mis-represented the situative perspective and that their 4 claims are incorrect, and that their framing of these claims is based on certain presuppositions of the cognitive perspective (1997). For example, their focus on how "tightly bound" knowledge is to the context in which it is acquired belies the cognitivist focus on knowledge acquisition (Greeno, 1997:6). In contrast, the situative perspective is interested in the practices that individuals have learned to participate.

Further reading

- Anderson, J. R., Greeno, J. G., Reder, L. M., & Simon, H. A. (2000). Perspectives on learning, thinking, and activity. Educational Researcher, 29, 11-13.

- Brown, A. L. (1992). "Design experiments:Theoretical and methodological challenges in creating in complext interventions in classroom settings". Journal of the Learning Sciences. 2 (2): 141–178. doi:10.1207/s15327809jls0202_2.

- Clancey, William J. (1997). Situated Cognition: On Human Knowledge and Computer Representation. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.2277/0521448719. ISBN 0-521-44871-9.

- "Special Issue: Situated Action". Cognitive Science. 17 (1). Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Jan-March 1993.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & Education. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83828-1.

- Gallagher, S., Robbins, B.D., & Bradatan, C. (2007). Special issue on the situated body. Janus Head: Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature, Continental Philosophy, Phenomenological Psychology, and the Arts, 9(2). URL: http://www.janushead.org/9-2/

- Greeno, J. G. (1994). Gibson's affordances. Psychological Review, 101 (2), 336-342.

- Greeno, J. G. (1997). On claims that answer the wrong question. Educational Research, 26(1), 5-17.

- Greeno, J.G., and Middle School Mathematics Through Applications Project Group (1998). The situativity of knowing, learning, and research. American Psychologist, 53(1), 5-26.

- Greeno, J. G. (2006). Authoritative, accountable positioning and connected, general knowing: Progressive themes in understanding transfer. Journal of the Learning Sciences 15(4) 539-550.

- Griffin, M. M. (1995). You can't get there from here: Situated learning, transfer, and map skills. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 20, 65-87.

- Hutchins, E. (1995). Cognition in the Wild. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press (A Bradford Book). ISBN 0-262-58146-9.

- Kirshner, D. & Whitson, J. A. (1997) Situated Cognition: Social, semiotic, and psychological perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum (ISBN# 0-8058-2038-8)

- Kirshner, D., & Whitson, J. A. (1998). Obstacles to understanding cognition as situated. Educational Researcher, 27(8), 22-28.

- Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in Practice. ISBN 0-521-35018-8.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr. ISBN 978-0-521-42374-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

See also

- Activity theory

- Distributed cognition

- Ecological psychology

- Embodied cognition

- Enactivism

- Relational frame theory

- Situational awareness

- Situated learning

References

- Anderson, J.R., Reder, L.M., Simon, H.A. (1996). Situated learning and education. Educational Researcher, 25 (4), 5-11.

- Bredo, E. (1994). "Reconstructing educational psychology: Situated cognition and Deweyian pragmatism". Educational Psychologist. 29 (1): 23–35. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2901_3.

- Brown, J. S. (1989). "Situated cognition and the culture of learning". Educational Researcher. 18 (1): 32–42.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Clancey, W. J (1993). "Situated action: A neuropsychological interpretation response to Vera and Simon". Cognitive Science. 17: 87–116.

- Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt (1990). "Anchored instruction and its relationship to situated cognition". Educational Research. 19 (6): 2–10.

- Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt. (1993). Anchored instruction and situated cognition revisited. Educational Technology March Issue, 52-70.

- Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt. (1994). From visual word problems to learning communities: Changing conceptions of cognitive research. In K. McGilly (Ed.) Classroom lessons: Integrating cognitive theory and classroom proactice. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

- Driscoll, M. P. (2004). Psychology of learning for instruction (3 ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 0-20-537519-7.

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). "A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality". Psychological Review. 95: 256–273. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Engle, R.A. (2006). "Framing interactions to foster generative learning: A situative explanation of transfer in a community of learners classroom". 15 (4): 451–498.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Eysenck, M. W., & Keane, M. T. (2005). Cognitive psychology (5 ed.). Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84169-359-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "location:New York" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gagne, R. M., Wager, W.W., Golas, K. C., & Keller, J. M. (2005). Principles of Instructional Design (5 ed.). Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. ISBN 0-534-58284-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "location:Belmont, CA" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gibson, James J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-898-59959-8.

- Glenberg, A. M. & Robertson, D. A. (1999). Indexical understanding of instructions. Discourse Processes, 28 (1), 1-26.

- Greeno, J. G. (1989). "A perspective on thinking". American Psychologist. 44: 134–141. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.134.

- Greeno, J. G. (1994). "Gibson's affordances". Psychological Review. 101: 336–342. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.101.2.336.

- Greeno, J. G. (1998). "The situativity of knowing, learning, and research". American Psychologist. 53 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.53.1.5.

- Greeno, J. G. (2006). Authoritative, accountable positioning and connected, general knowing: Progressive themes in understanding transfer. J. of the Learning Sciences 15(4) 539-550.

- Hart, L. A. (1990). Human Brain & Human Learning. Books for Educators. ISBN 978-0962447594.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "location:Black Diamond, WA" ignored (help) - Kugler, P. N., Shaw, R. E., Vicente, K. J., & Kinsella-Shaw, J. (1991). The role of attractors in the self-organization of intentional systems. In R. R. Hoffman and D. S. Palermo (Eds.) Cognition and the Symbolic Processes. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Lave, J. (1977). "Cognitive consequences of traditional apprenticeship training in West Africa". Anthroppology and Education Quarterly. 18 (3): 1776–180.

- Markman, A. B., & Brendl, C. M. (2005). "Constraining theories of embodied cognition". Psychological Science. 16 (1): 6–10. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2005.00772.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Niedenthal, P. M. (2007). "Embodying emotion". Science. 316: 1002–1005. doi:10.1126/science.1136930. PMID 17510358.

- Ormrod, J. E. (2004). Human learning (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. ISBN 0-13-094199-9.

- Palinscar, A.S., & Brown, A.L. (1984). "Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and monitoring activities". Cognition and Instruction. 1: 117–115. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci0102_1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Roth, W-M (1996). "Knowledge diffusion in a grade 4-5 classroom during a unit on civil engineering: An analysis of a classroom community in terms of its changing resources and practices". Cognition and Instruction. 14 (2): 179–220. doi:10.1207/s1532690xci1402_2.

- Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2003). Knowledge building. In J. W. Guthrie (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Education (2nd Ed., pp. 1370-1373). New York: Macmillan Reference.

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-61556-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Shaw, R. E., Kadar, E., Sim, M. & Repperger, D. W. (1992). The intentional spring: A strategy for modeling systems that learn to perform intentional acts. Journal of Motor Behavior 24(1), 3-28.

- Weiner, B. (1994). "Ability versus effort revisited: The moral determinants of achievement evaluation and achievement as a moral system". Educational Psychology Review. 12: 1–14. doi:10.1023/A:1009017532121.

- Wilson, M. (2002). "Six views of embodied cognition". Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 9 (4): 625–636.

- Wilson, B.B., & Myers, K. M. (2000). Situated Cognition in Theoretical and Practical Context. In D. Jonassen, & S. Land (Eds.) Theoretical Foundations of Learning Environments. (pp. 57-88). Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Young, M. F. , Kulikowich, J. M., & Barab, S. A. (1997). The unit of analysis for situated assessment. Instructional Science, 25(2), 133-150.

- Young, M., & McNeese, M.(1995). A Situated Cognition Approach to Problem Solving. In P. Hancock, J. Flach, J. Caid, & K. Vicente (Eds.) Local Applications of the Ecological Approach to Human Machine Systems.(pp.359-391). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Young, M. (2004). An Ecological Description of Video Games in Education. Proceedings of the International Conference on Education and Information Systems Technologies and Applications (EISTA), July 22, Orlando, FL, pp.203-208.