Talk:Monty Hall problem: Difference between revisions

→Discussion: yes I agree, but tread carefully here. |

Rick Block (talk | contribs) →Discussion: deleting Problem section? with a lead-in saying another solution is coming, I'd be OK |

||

| Line 551: | Line 551: | ||

Well I'm not really happy with point 2 & 3 of the simple solution, but i'd still consider it as acceptable (in connection with the rest). I suggest to move this over to the mediation and see whether it can be revived with that approach.--[[User:Kmhkmh|Kmhkmh]] ([[User talk:Kmhkmh|talk]]) 13:20, 17 May 2010 (UTC) |

Well I'm not really happy with point 2 & 3 of the simple solution, but i'd still consider it as acceptable (in connection with the rest). I suggest to move this over to the mediation and see whether it can be revived with that approach.--[[User:Kmhkmh|Kmhkmh]] ([[User talk:Kmhkmh|talk]]) 13:20, 17 May 2010 (UTC) |

||

Martin - Are you suggesting deleting the existing "Problem" section, or is this an oversight? Either way, what you are suggesting is the article wholeheartedly endorse the POV of those sources presenting "simple" solutions, completely ignoring the alternate POV until a section titled "Academic solution". Your bullet in this section "There is no attempt to bury or hide the points raised by Morgan and other sources" is funny, because this is apparently ''exactly'' your intent with the structure you're proposing. If one POV is so hard to understand that it takes multiple sections to explain (and, ironically, you're suggesting the "simple" solution requires an extensive discussion to be convincing), then to be even remotely NPOV the fact that there are two main approaches needs to made clear ''before'' delving into details. I'd be OK with a structure like: |

|||

:'''Lead''' |

|||

::''As is.'' |

|||

:'''Problem''' |

|||

::''As is.'' |

|||

:'''Solution''' |

|||

::''Wording that makes it clear there are two main solution approaches, perhaps like this:'' |

|||

::There are two main approaches to solving the Monty Hall problem based on a subtle difference in interpretation of the problem statement. Most popular sources present simple solutions based on the overall probability of winning the car by switching versus staying with the player's initial choice. The other main approach to solving the problem, used primarily in academic sources, is to treat it as a [[conditional probability]] problem. |

|||

:'''Solutions based on the overall probability of winning by switching versus staying''' |

|||

:'''Solutions based on conditional probability''' |

|||

But without some kind of lead-in that says another solution is coming, in my book what you're suggesting is not NPOV. -- [[user:Rick Block|Rick Block]] <small>([[user talk:Rick Block|talk]])</small> 14:32, 17 May 2010 (UTC) |

|||

Revision as of 14:32, 17 May 2010

| This is the talk page for discussing changes to the Monty Hall problem article itself. Please place discussions on the underlying mathematical issues on the Arguments page. If you just have a question, try Wikipedia:Reference desk/Mathematics instead. |

| This article is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Please add the quality rating to the {{WikiProject banner shell}} template instead of this project banner. See WP:PIQA for details.

Please add the quality rating to the {{WikiProject banner shell}} template instead of this project banner. See WP:PIQA for details.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monty Hall problem is a featured article; it (or a previous version of it) has been identified as one of the best articles produced by the Wikipedia community. Even so, if you can update or improve it, please do so. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| This article appeared on Wikipedia's Main Page as Today's featured article on July 23, 2005. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| This is the talk page for discussing improvements to the Monty Hall problem article. This is not a forum for general discussion of the article's subject. |

Article policies

|

| Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

| Archives: Index, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39Auto-archiving period: 20 days |

Archives |

|---|

|

Would it be accurate to say

Since 2/3 doors are the wrong choice, the chances are that you picked the wrong door in the first place, so when shown the other wrong one, the remaining one is more likely to be correct since it's not the one you know is wrong, and not the one you know to be probably wrong. --66.66.187.132 (talk) 03:45, 5 May 2010 (UTC)

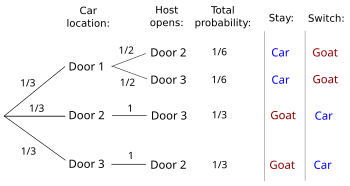

- That's one way to look at it. Another way to look at it, given you've picked door 1 and host has opened door 3, is that the host has a 100% chance of opening door 3 if the car is behind door 2 (1/3 chance of this happening) but only a 50% chance of opening door 3 if the car is behind door 1 (1/6 chance of this happening). The situation is similar if the host opens door 2 (1/3 chance the car is behind door 3 and 1/6 chance it's behind door 1). So whichever door the host opens, the chances are twice as good that the car is behind the other unopened door than the one you originally picked - because the host has 2 choices for which door to open if the car is behind the door you pick, but has only one choice if the car is not behind the door you originally picked. -- Rick Block (talk) 04:06, 5 May 2010 (UTC)

Yes, 66.66.187.132, that's all there is to it. The 2/3 chance that your door choice is wrong is not changed by the host's actions. And since the total probability has to add up to 1, the remaining door has only a 1/3 chance of being wrong (more importantly, a 2/3 chance of being the car). Glkanter (talk) 05:55, 5 May 2010 (UTC)

This article is overly complicated, confusing and just plain wrong in more than one place.

The OVERALL odds of winning the game ARE in fact 1/2!

Yes if you play the "switch strategy" the odds of winning are 2/3 and staying will result in 1/3. However the contestant is asked to make to choices: 1) choose one of three doors 2) stay or switch after a goat is revealed

If both of these choices are made randomly than the odds of winning the car are 1/2. One can prove it two ways:

1) averaging strategies: one third plus two thirds is one, one over two is one half.

2) one car, two doors (what are you not getting here?)

The event matrices are good visual descriptions on how switching improves your odds but the article fails to differentiate between the odds of winning with a random selection and acting on a strategy of switching or staying.

Explaining this will leave the reader more satisfied. I would be happy to rewrite the article if that bot will stop reverting my edits. Whatever, it just wouldn't be wikipedia if articles weren't full of wrong. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 101glover (talk • contribs) 09:29, 5 May 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, you are correct if all choices made by the player are random the probability that the player will win is 1/2 but that is not what the Monty Hall problem is all about. The most famous statement of the problem is given at the start of the article:

- Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to pick door No. 2?" Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

- Note the question that I have put in bold. The questioner wants to know if it is better to swap or not. Vos Savant answered correctly that it is better to swap and that you double your odds of winning if you do so. Do you agree with this? Martin Hogbin (talk) 10:57, 5 May 2010 (UTC)

- That's not enough. You have to include the condition that Monty ALWAYS behaves this way. That is, he ALWAYS chooses a door that he knows has a goat and ALWAYS opens that door. If you give Monty the CHOICE of opening the door or not, then there is no unique answer. For example, Monty From Hell: Monty only gives you a choice if you have chosen the door with the prize. Angelic Monty: Monty only gives you a choice if you have chosen a door with a goat.

- Vos Savant was careless when she originally stated the problem, because she neglected to state this condition clearly (actually, at all). Bill Jefferys (talk) 23:25, 5 May 2010 (UTC)

- To justify the answer that the chance of winning by switching is 2/3 knowing which door the player picked and which door the host opened 1) the car must be placed randomly, 2) the host must always open a losing door and make the offer to switch, and 3) the host must choose between two losing doors with equal probability. It can certainly be argued that vos Savant implied all of these, and most people apparently assume these conditions whether they're explicitly included in the problem statement or not.

- However, back to the original objection here, the problem is definitely not talking about the chances if the player makes a random choice of whether to switch or not. Perhaps a more clear way to ask the question (assuming the clarifications about the car placement and host's behavior) is to ask about an expected frequency, i.e. if the show were on 900 times and the players initially picked a random door, how many of the players who pick door 1 and then see the host open door 3 would win if they switch?

- If their initial pick is random, we'd expect about 300 players to initially pick door 1. If the car is placed randomly, of the 300 who picked door 1 we'd expect the car to be behind each door about 100 times. If the host opens door 3, it's because the car is behind door 2 (100 times) or the host has chosen to open door 3 when the car is behind door 1 (50 times). So, there will be about 150 players who choose door 1 and see the host open door 3, and of these 100 win if they switch. The chance of winning the car by switching (given the player picks door 1 and sees the host open door 3) is therefore 100/150 = 2/3. Of course, if all 150 of these players randomly choose whether to switch, about 75 will switch and 75 will stay with their initial choice. Of the 75 who switch about 2/3 (50) will win the car and of the 75 who stay about 1/3 (25) will win the car, so about 75 altogether (i.e. 1/2). This doesn't mean the chances of winning by switching are 1/2 but rather the chances of winning by making a random choice of whether to switch are 1/2.

- See the difference? -- Rick Block (talk) 04:34, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- As Rick has said, there were some significant assumptions made by vos Savant that she did not male clear in her reply. These have been the subject of later criticism of her response but they are fully covered in this article.

- The point being made by 66.66.187.132 was a different one. He was talking about the overall probability of winning if the player chooses randomly whether to switch or not, which is 1/2 but which is a question that I have never seen asked before and is not generally considered to be the Monty Hall problem. I guess he was misled by use of the term 'overall'. Martin Hogbin (talk) 08:53, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- Martin - of course you've seen this question before. It's vos Savant's "little green woman" variant (from her 3rd column about the problem). -- Rick Block (talk) 13:16, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- Yes you are quite right Rick, I had forgotten about that. Martin Hogbin (talk) 14:56, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- Martin - of course you've seen this question before. It's vos Savant's "little green woman" variant (from her 3rd column about the problem). -- Rick Block (talk) 13:16, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- A lot of grief could be avoided if the article, instead of quoting vos Savant's flawed statement, instead led off with a correct statement of the problem, for example, as Martin Gardner originally put it (I don't have a copy of his book available but I am morally certain that he would have been careful to give an accurate statement of the problem).

- As it is, leading off with vos Savant's flawed version and then trying to clean it up in the next paragraph or two just sows confusion. Bill Jefferys (talk) 17:14, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- Interesting suggestion. Thanks for your input. Glkanter (talk) 17:49, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- I assume by "Savant's flawed version" you actually mean Whitaker's version, in that case the answer is no. We cannot use Gardner because strictly speaking his original problem is not MHP and we cannot replace the ambiguous "original" MHP (Whitaker) by a later non ambiguous one. This is because WP is not in the business of defining the problem but has to report as it is and furthermore the ambiguity is a central part of the problem itself and much of its controversy.--Kmhkmh (talk) 18:41, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- I disagree. By far, the most notable and well known version of the MHP is as a mathematical puzzle in which all necessary assumptions are made for the solution to be simple with the player having a 2/3 chance of winning if they switch. This was actually the question that vos Savant intended to answer. Unfortunately, she did not make some of her assumptions clear until after she had given her reply. Martin Hogbin (talk) 18:50, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- Frankly you lost me completely here. Earlier one of your main arguments was that the MHP is not a math problem/puzzle and now you're telling me it is? That aside, I don't quite see, where your statement contradicts what I've wrote above, so where is the actual disagreement?--Kmhkmh (talk) 19:23, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- I disagree. By far, the most notable and well known version of the MHP is as a mathematical puzzle in which all necessary assumptions are made for the solution to be simple with the player having a 2/3 chance of winning if they switch. This was actually the question that vos Savant intended to answer. Unfortunately, she did not make some of her assumptions clear until after she had given her reply. Martin Hogbin (talk) 18:50, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- Martin - I can't tell who you're disagreeing with here, Bill or Kmhkmh. I thought you have consistently argued that the most notable and well known version is Whitaker's (as published by vos Savant). In the current structure of the article (problem, solution, explanations, variants, history) the problem section starts with Whitaker's version, mentions the ambiguities, and presents a fully unambiguous version. This understanding of the problem (which I think is the mathematical puzzle you're referring to) is the topic of the solution and explanations sections. Variations are covered in the variants section. I think this structure matches the bulk of the references, many of which use Whitaker's version (modulo minor misquotings) but then present a solution that actually applies only to the fully unambiguous version (usually ignoring the ambiguities).

- To Bill's point - I think the article essentially already does this. Although the "Problem" section starts off with Whitaker's version it proceeds directly into an unambiguous version. For summary in the lead, Whitaker's version is used (since it's more well known, and shorter) but even in the lead the fact that this version of the problem is underconstrained is mentioned.

- And, finally, I completely agree with Kmhkmh. We can't change the problem statement (or solutions) to our liking but need to take what's published about it. We're not writing an original paper about this problem - we're summarizing what the published literature has to say about it. -- Rick Block (talk) 19:31, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- In case i wasn't quite clear above, I'm fine with the current introduction/lead as it is. I was under the impression Bill suggested to change that and replace it by a non ambiguous problem version. While that approach is fine for an article on MHP published elsewhere, it should not/cannot be handled in WP in such a manner for the reason stated above.--Kmhkmh (talk) 19:42, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- And, finally, I completely agree with Kmhkmh. We can't change the problem statement (or solutions) to our liking but need to take what's published about it. We're not writing an original paper about this problem - we're summarizing what the published literature has to say about it. -- Rick Block (talk) 19:31, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

You know, if I were to read today's comments a certain way, I could conclude that the article is not only at the level of a Featured Article, but has attained Nirvana, and could not possibly be improved upon by mortal editors. Kudos! Glkanter (talk) 19:50, 6 May 2010 (UTC)

- @Rick and Kmhkmh, this is meant to be an encyclopedia article on the Monty Hall problem not a literature review on the subject. Everything we write should be supported by reliable sources but the sources do not, indeed cannot, tell us how to compose the article. Martin Hogbin (talk) 13:04, 7 May 2010 (UTC)

What is notable

The most notable statement of the problem is undoubtedly that of Whitaker but, as we all know, this statement leaves out much of the information needed to solve the problem and thus needs interpretation. The most notable interpretation of Whitaker's question is undoubtedly that of vos Savant. She, eventually, made clear that she had interpreted the problem as a simple mathematical puzzle, in which the host always offers the swap and the host always opens a legal door randomly to reveal a goat. This simple interpretation turns out to be exactly the same as the question asked and later clarified by Selvin some years earlier. This is the notable problem formulation because it resulted in thousands of letters claiming the answer was 1/2 and not 2/3. No one argued that it might make a difference which door the host opened when he had a choice, or that the player had to make her choice before the host revealed a goat. The only point in question was whether the answer was 1/2 or 2/3. This simple problem formulation, in which it is quite obvious that it makes no difference which legal door the host opens, then found its way into countless puzzle books and web sites and it is by far most the important, interesting, and notable version and it is the one that we should primarily be addressing here.

A second, and far less well known MHP, was later created by Morgan et al who showed that in their, somewhat perverse, interpretation of the problem, it could matter which door the host opened when he had a choice. This is indeed an interesting point for those starting to study conditional probability as it shows how a seemingly unimportant detail can have a significant effect on the a probability, and this version should, of course, be addressed here also.

However, nothing in WP policy, or common sense, tells us that the Morgan interpretation should control the whole article including dictating how we should address and fully explain the solution to the simple problem. That is the most important function of this article and it is up to editors here to decide how to do it. Martin Hogbin (talk) 13:46, 7 May 2010 (UTC)

- Clear and precise formulation! Thank you. – Makes it "to the point", finally showing the real problem: (delete this if you like)

In exactly 2/3 of millions the player will win by switching, and only in 1/3 of millions she will win by staying. For most people it is hard to believe, let alone to understand. But a fact. No doubt. The famous 50:50 paradoxon. But no one can change this fact, neither Morgan.

Some smart, but totally fabricated, say perverse interpretation occured: If the host gives information about the actual status (although he never can change the actual, current status!), e.g. having a preference for opening one particular non selected door, then he can meet his preference in 2/3 of millions only:

- In 1/3 (when he has got two goats to choose from), i.e. when staying will win!

And in another half of 2/3 (when he got the car and just one goat, and when the goat by chance is behind his preferred door), i.e. when switching will win!

- In these 2/3 of millions, both switching and staying in average will have a chance of 1/2 each.

But in 1/3 of millions the car will be behind his preferred door, and by exceptionally opening the "avoided and unusual" door he shows that switching will win anyway with a chance of 1. But the host never can change the current status, though. He just may indicate information about the actual constellation. Why not opening all three doors at once? But all of that is a dishonorable game, when secret facts about the actual constellation should be revealed. Just suitable for students in probability. Not really affecting the famous 50:50 paradoxon in any way.

- This fact being emphasized in every university, and you can find it in multiple internet pages of universities all over the world. This should clearly be stated in the article, and Morgan et al. may not be allowed to confuse. Facts should be presented clearly in WP. Sources? Wherever you have a look. Regards, --Gerhardvalentin (talk) 22:58, 7 May 2010 (UTC)

- I would say that my problem with the introduction to the article is that the discussion assumes that the reader has information that hasn't already been stated to him. For example, it says:

- However, such possible behaviors had little or nothing to do with the controversy that arose (vos Savant 1990), and the intended behavior was clearly implied by the author (Seymann 1991).

- What is the "intended behavior"? The reader of the article does not know at this point, and will only read about it if she reads further. I would suggest something like this:

- However, such possible behaviors had little or nothing to do with the controversy that arose (vos Savant 1990), and the intended behavior -- that Monty must open a door that he knows has a goat...(add whatever you need) -- was clearly implied by the author (Seymann 1991).

- Making it clear in the initial section what the "intended behavior" is supposed to have been would go a long way towards alleviating my discomfort with the article as it stands.

- Martin has correctly diagnosed the real point. People answer the "notable problem" incorrectly, even if it is stated unambiguously. The article needs to make clear what the "notable problem" is in the introduction. As it stands, we have an introduction to the history of the popular perception of the problem and the controversy that the Parade article engendered, but in what seems to me to be a confusing way, since the introduction never says what the "notable problem" is! Bill Jefferys (talk) 00:26, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

- Bill, you are not the first person to make that point and you will most likely not be the last. I would like to change this article to give a complete, clear and, convincing solution to the basic MHP first and then proceed to the potential complications but there is a minority of editors who have resolutely resisted any change. Martin Hogbin (talk) 21:06, 9 May 2010 (UTC)

@Martin: From WP:NPOV: Neutral point of view (NPOV) is a fundamental Wikimedia principle and a cornerstone of Wikipedia. All Wikipedia articles and other encyclopedic content must be written from a neutral point of view, representing fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias, all significant views that have been published by reliable sources. This is non-negotiable and expected of all articles and all editors.

Whether the "most notable interpretation of Whitaker's question is undoubtedly that of vos Savant" is the wrong question to be asking. The right question is what is the proportion of reliable sources that agree with her interpretation.

Bill hasn't been directly involved in this dispute, but for his benefit the issue here is whether vos Savant's solution, which mathematically solves for the overall probability of winning by switching given the player has picked door 1 (as opposed to the conditional probability of winning given the player has, for example, picked door 1 and has seen the host open door 3) should be the primary way the solution is presented. The solutions Martin favors make no attempt to justify that the probability they compute is the same as the conditional probability, and omit any mention of the critical assumption that makes these two probabilities necessarily equal (i.e. that the host choose between two goats randomly with equal probability) - as if the question asks about the overall probability rather than the conditional probability. Of course you CAN argue that these two probabilities must be the same (for example, if the problem is assumed to be symmetric - which it is if and only if the host chooses between two goats equally), but none of the sources presenting these kinds of solutions do this, so the article can't on their behalf. Furthermore, Martin desires to relegate any mention of a conditional solution to a "variants" section.

My argument is that this presentation would not represent "fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias, all significant views that have been published by reliable sources". In my reading of the literature there are at least as many sources that explicitly address the conditional probability as ignore it, and in addition a significant number that explicitly criticize solutions that do not address the conditional probability. Martin's claim that the interpretation of Morgan et al. (this reference) is less well known, even perverse (?!), could not IMO be further from the truth.

We're already in formal mediation about this, see Wikipedia talk:Requests for mediation/Monty Hall problem. Further argument outside of the mediation process seems relatively pointless. -- Rick Block (talk) 04:19, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

- We are nominally in formal mediation but nothing has happened for ages now. Andrevan has made clear that he is happy for discussion to continue outside the mediation. Indeed it is better for us to discuss here rather than on the mediation page.

- Neutral POV is fine, but that does not make an article into a literature survey. The question is one of notability. Google the MHP and you will see almost nothing about the door that the host chooses. An Open University site even directs readers here, saying, 'The very informative article on the Monty Hall problem in the Wikipedia online encyclopaedia has several other arguments that might persuade you [my emphasis]. The whole and only reason that the MHP is notable is that people think that the answer is 1/2 not 2/3. This is not my POV it is what overwhelming evidence tells us. Even Gill, an academic studying the MHP was not aware of the Morgan paper. It is, by any measure, a sideline or an academic diversion from the real problem, which is a simple mathematical puzzle, which everybody gets wrong. Martin Hogbin (talk) 10:36, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

- Martin - the question is not notability (or popularity), it's prevalence of a particular viewpoint among reliable sources. The policy is set up this way specifically so that the predominant published viewpoint (or viewpoints) is what is presented here regardless of popularity. I absolutely agree the MHP is notable because people get it wrong, but I think you're wrong about what problem most people think they're solving when they end up with 1/2 vs. 2/3. 1/2 is the "obvious" (but wrong) answer for the conditional problem (player has picked a specific door and can see which door the host has opened). 2/3 is the obvious (and right) answer for the unconditional problem (overall chance of winning by switching regardless of which door the host opens). By not distinguishing these as different problems what vos Savant and the others presenting "simple" solutions (never explicitly connected to any conditional case) are saying is effectively that the problem is the unconditional problem and (by implication) the answer to the conditional problem (whether it's 1/2 or anything else) is fundamentally irrelevant. Another (more generous) way to look at it is these solutions solve the conditional problem indirectly by solving a slightly different problem that has the same answer (but only given a specific unstated assumption - i.e. symmetry, or equivalently, that the host chooses between two goats equally). What Morgan et al. and the other sources you don't like are saying is that the problem is explicitly about the conditional probability so you must solve it conditionally, which you can do directly.

- Are you denying that Morgan et al. is only one of many reliable sources that take this viewpoint? I've previously offered at least 5. How many would it take to convince you that this is not a "sideline or an academic diversion from the real problem" but rather a widely held significant view? -- Rick Block (talk) 17:17, 8 May 2010 (UTC

- Hardly anyone finds the anwer 1/2 obvious, for either the conditional or unconditional case (in fact I doubt that most people distinguish the two cases). The idea that this might be the case seems to be unique to you. We cannot base this article on your own theory.

- I am well aware that a number of statistics text books and papers mention the conditional nature of the problem, that is because the conditional aspect of the problem is of value in teaching elementary conditional probability but it is of little interest to most people, and for that matter probability experts. Also I accept that, if you want to be pedantic, even when the host chooses a legal door randomly, the problem is one of conditional probability. I even have no problem in including this in the article. However the fact is that the host's choice of legal door makes no difference to the probability of winning in this case and the vast majority of sources (online and written) do not consider this fact important. Most sources treat the MHP as a simple puzzle in which the host door choice is unimportant and that is what we must do. Martin Hogbin (talk) 21:42, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

- What I mean by the 1/2 answer being "obvious" is that it is the answer most people immediately see as "correct" (since there are two closed doors and one open door). The problem for which this answer is "obvious" is the conditional problem, i.e. the situation faced by a player who has (for example) selected door 1 and has seen the host open door 3. This idea is not unique to me - it's also what Krauss & Wang say ("... most participants take the opening of Door 3 for granted, and base their reasoning on this fact. In a pretest, ... we saw 35 out of the remaining 36 participants (97%) indeed drew an open Door 3"). So, again, how many sources does it take to convince you that the viewpoint that the problem is inherently conditional is a mainstream POV that, per WP:NPOV policy MUST be represented fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias? -- Rick Block (talk) 22:32, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

- The connection between the problem being conditional and the difficulty people have in solving it correctly is your own pet theory. K&W certainly do not make this connection in their paper. Their main point is that excessive information, in particular door numbers, only serves to confuse people. Martin Hogbin (talk) 20:57, 9 May 2010 (UTC)

- Would you please answer the question? How many sources does it take to convince you that the viewpoint that the problem is inherently conditional is a mainstream POV that, per WP:NPOV policy MUST be represented fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias? -- Rick Block (talk) 21:50, 9 May 2010 (UTC)

- I have already agreed that the problem is one of conditional probability, just like every other probability problem. The point that we are arguing about is how to best give a solution to the problem in this article and, in particular, whether the condition that the host opens a specific door should be considered important in our initial description of the problem. The vast majority of sources, online and written, do not consider this a significant condition and do not consider it in their solutions. Selvin, when he originally posed the problem, specified that the host would choose randomly when he had a choice of goat doors, with the clear intention of making the host's choice of legal door irrelevant to the problem. Vos Savant continued this tradition by making the same assumption in her solution. Most sources that addresses the problem proceed on this basis. There are a number of sources, clearly aimed at those studying conditional probability, that consider the case where the host may not choose a legal door randomly and thus the specific door opened by the host becomes an important condition of the problem. This case, however, is of minority academic interest, and is one which should influence the structure of our article.

- I am not aware of any source before 1991 that specifically considers the door that the host opens when he has a choice to be significant. Please tell me if you know of one. Martin Hogbin (talk) 11:29, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Would you please answer the question? How many sources does it take to convince you that the viewpoint that the problem is inherently conditional is a mainstream POV that, per WP:NPOV policy MUST be represented fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias? -- Rick Block (talk) 21:50, 9 May 2010 (UTC)

- The connection between the problem being conditional and the difficulty people have in solving it correctly is your own pet theory. K&W certainly do not make this connection in their paper. Their main point is that excessive information, in particular door numbers, only serves to confuse people. Martin Hogbin (talk) 20:57, 9 May 2010 (UTC)

- What I mean by the 1/2 answer being "obvious" is that it is the answer most people immediately see as "correct" (since there are two closed doors and one open door). The problem for which this answer is "obvious" is the conditional problem, i.e. the situation faced by a player who has (for example) selected door 1 and has seen the host open door 3. This idea is not unique to me - it's also what Krauss & Wang say ("... most participants take the opening of Door 3 for granted, and base their reasoning on this fact. In a pretest, ... we saw 35 out of the remaining 36 participants (97%) indeed drew an open Door 3"). So, again, how many sources does it take to convince you that the viewpoint that the problem is inherently conditional is a mainstream POV that, per WP:NPOV policy MUST be represented fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias? -- Rick Block (talk) 22:32, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

- At this point I frankly couldn't care less whether you agree the problem is conditional or not - the question is about the prevalence of views expressed in reliable sources. What we're arguing about is whether it is appropriate to marginalize the POV expressed by Morgan et al. and others that the solution should be explicitly conditional, and the corresponding criticism of solutions that do not explicitly address any conditional case. You're claiming this POV conflicts with that of "the vast majority of sources". My question is how many sources do I need to cite to convince you that this is NOT a marginal POV, but a POV that is at least as common among reliable sources as (say) vos Savants? The date of publication is not significant to this question, although Selvin's second letter does consider how the host opens a door when he has a choice to be significant. So, once more, would you please answer the question? How many sources does it take to convince you that the viewpoint that the problem is inherently conditional is a mainstream POV that, per WP:NPOV policy MUST be represented fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias?-- Rick Block (talk) 14:19, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Firstly, Selvin's second letter defines the host to choose randomly because Selvin knows that this could be significant, if he had not defined the host to act that way. In other word he makes toe hosts random legal choice clear in order to avoid the very issue we are arguing about.

- To answer your question of how many sources you need to quote to show that Morgan's approach is as common as vos Savant's, maybe a hundred would do it.

- Finally, although it is my personal POV that Morgan's approach is a marginal academic diversion, I am not trying to push this in the article. As I have often said, as an attempt at compromise, I am perfectly willing to give Morgan's solution equal space to the simple solutions in the article. I simply want to ensure that the simple solutions are fully, completely, and convincingly explained first - the way that all good text books do things. It is you who is pushing your POV that the Morgan paper somehow has the power to direct the structure of the article for us. Martin Hogbin (talk) 16:24, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- At this point I frankly couldn't care less whether you agree the problem is conditional or not - the question is about the prevalence of views expressed in reliable sources. What we're arguing about is whether it is appropriate to marginalize the POV expressed by Morgan et al. and others that the solution should be explicitly conditional, and the corresponding criticism of solutions that do not explicitly address any conditional case. You're claiming this POV conflicts with that of "the vast majority of sources". My question is how many sources do I need to cite to convince you that this is NOT a marginal POV, but a POV that is at least as common among reliable sources as (say) vos Savants? The date of publication is not significant to this question, although Selvin's second letter does consider how the host opens a door when he has a choice to be significant. So, once more, would you please answer the question? How many sources does it take to convince you that the viewpoint that the problem is inherently conditional is a mainstream POV that, per WP:NPOV policy MUST be represented fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias?-- Rick Block (talk) 14:19, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Defining the host's choice between two losers as random doesn't avoid the issue we're arguing about - it is the issue we're arguing about. The host's choice in this case doesn't matter and doesn't need to be specified if the question is interpreted unconditionally (the average chance of winning by switching is 2/3 no matter how the host chooses between two losers) - it only matters if the question is interpreted conditionally (the conditional chance of winning is 2/3 if and only if the host chooses randomly between two losers). So, if you agree it matters, you're agreeing the question is the conditional question (and, vice versa).

- Yes, that is exactly why Selvin did define the host to choose a legal door randomly, to avoid all this argument. Martin Hogbin (talk) 19:15, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Defining the host's choice between two losers as random doesn't avoid the issue we're arguing about - it is the issue we're arguing about. The host's choice in this case doesn't matter and doesn't need to be specified if the question is interpreted unconditionally (the average chance of winning by switching is 2/3 no matter how the host chooses between two losers) - it only matters if the question is interpreted conditionally (the conditional chance of winning is 2/3 if and only if the host chooses randomly between two losers). So, if you agree it matters, you're agreeing the question is the conditional question (and, vice versa).

- Perhaps we should ask the mediator about this, but are you seriously suggesting it would take 100 references to convince you that the POV that the question being asked is the conditional question is a common POV? This seems like a completely unreasonable stance to me. I'd be willing to find as many references that take this POV as you can find that take vos Savant's POV.

- Yes, there are far more sources which do not consider it important which legal door the host opens. Try a Google search on the MHP. You seemed to want to do a source count although we both probably agree that this is not the way to decide. Martin Hogbin (talk) 19:15, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Perhaps we should ask the mediator about this, but are you seriously suggesting it would take 100 references to convince you that the POV that the question being asked is the conditional question is a common POV? This seems like a completely unreasonable stance to me. I'd be willing to find as many references that take this POV as you can find that take vos Savant's POV.

- I'm not saying the Morgan paper should direct the structure of the article. What I'm saying is that the article must not present the simple solution as if it is the main, true, correct answer agreed by all sources - since it clearly is not - but rather the article should present both types of solutions as valid. The solution section I've proposed (per this thread) attempts to do this (and it is a compromise since my POV is that the problem is conditional and the unconditional solutions don't quite address it). Your counter suggestion continues to be to present a fully fledged unconditional solution (matching your POV) deferring any mention of a conditional solution or any criticism of the unconditional solutions to an "experts only", academic diversion section. You're insisting your POV dominate the article, not me. -- Rick Block (talk) 18:22, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Rick, where have I ever suggested that we, 'present the simple solution as if it is the main, true, correct answer agreed by all sources'? Let me explain one more time. We first present the simple solution, with no comment that it is either complete or incomplete. This is exactly what the sources that present such solutions do. It is also what most good textbooks do, they start with a simple explanation. Then, we present Morgan's argument that the simple solution is incomplete. We state their argument in full together with theit solution and supporting sources. At this time we should also present sources which criticise Morgan. Martin Hogbin (talk) 19:15, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- I'm not saying the Morgan paper should direct the structure of the article. What I'm saying is that the article must not present the simple solution as if it is the main, true, correct answer agreed by all sources - since it clearly is not - but rather the article should present both types of solutions as valid. The solution section I've proposed (per this thread) attempts to do this (and it is a compromise since my POV is that the problem is conditional and the unconditional solutions don't quite address it). Your counter suggestion continues to be to present a fully fledged unconditional solution (matching your POV) deferring any mention of a conditional solution or any criticism of the unconditional solutions to an "experts only", academic diversion section. You're insisting your POV dominate the article, not me. -- Rick Block (talk) 18:22, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Since the current version effectively does what you say, i.e. "first present the simple solution, with no comment that it is either complete or incomplete" and then "present Morgan's argument that the simple solution is incomplete", and you're still arguing about this I can only infer you must mean something different. What you've said before is you want to move "aids to understanding" before "Morgan's argument" (with criticisms of this argument) which has the form of a more or less complete article, followed by a controversial objection. This form conveys that the first section is the generally accepted (main, true, correct) answer and what comes later is not - i.e. it structurally makes your POV dominate the article. -- Rick Block (talk) 23:24, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

@Bill - regardless of the above, we can work on the lead. Perhaps the paragraph following the quoted problem description could say:

- As the player cannot be certain which of the two remaining unopened doors is the winning door, most people assume that each of these doors has an equal probability and conclude that switching does not matter. In the usual interpretation of the problem the host always opens a door, always makes the offer to switch, and randomly chooses which door to open if both hide goats. Under these conditions, the player should switch—doing so doubles the probability of winning the car, from 1/3 to 2/3.

Would that address your concern? -- Rick Block (talk) 04:19, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

- @Rick - Yes, that would address my concern. Thanks! Bill Jefferys (talk) 21:23, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

...and this simple solution distributes equally over any and all door selection and door revealed pairings.

I read Selvin's original table solution as indicating that all combinations are equally likely.

I get the feeling that this is what is being argued. Glkanter (talk) 23:31, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

- No, what is being argued is whether the the problem is about the unconditional probability (i.e. the overall chance of winning by switching), or the conditional probability (the chance of winning by switching if you've, for example, picked door 1 and have seen the host open door 3). What Selvin says about this is "The basis to my solution is that Monty Hall knows which box contains the keys and when he can open either of two boxes without exposing the keys, he chooses between them at random." For the unconditional problem, how the host chooses between two incorrect choices is irrelevant - the answer is 2/3 chance of winning by switching no matter how the host picks between two goats. That Selvin considered the host picking between two incorrect choices part of the basis of his solution clearly implies he was thinking the problem was asking about the conditional probability. Moreover, his alternate solution computes the conditional probability. -- Rick Block (talk) 23:56, 8 May 2010 (UTC)

- I agree, "The basis to my solution is that Monty Hall knows which box contains the keys and when he can open either of two boxes without exposing the keys, he chooses between them at random..." and this simple solution distributes equally over any and all door selection and door revealed pairings. Glkanter (talk) 00:55, 9 May 2010 (UTC)

- If the host chooses a door hiding a goat uniformly at random, the conditional and unconditional answers are exactly equal. This fact is quite clear without the use of conditional probability. Martin Hogbin (talk) 18:29, 9 May 2010 (UTC)

- How many sources present an unconditional answer making no mention of whether it must be the same as the conditional answer?

- It is not possible to answer this question. Hundreds of sources present an answer that is the same as both the unconditional answer and the symmetrical conditional answer, namely 2/3. These sources, quite sensibly, do not bother to distinguish between these cases. Martin Hogbin (talk) 15:53, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- How many sources present an unconditional answer making no mention of whether it must be the same as the conditional answer?

- How many sources present a conditional answer?

- I have not counted them. Maybe a dozen or so. I am sure that you can tell me. Martin Hogbin (talk) 15:53, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- How many sources present a conditional answer?

- How many sources criticize sources only presenting an unconditional answer as not exactly answering the question? -- Rick Block (talk) 21:09, 9 May 2010 (UTC)

- Again, you will know better than I will. It is clear that these are all based on one source, since no source did this before 1991. Martin Hogbin (talk) 15:53, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- How many sources criticize sources only presenting an unconditional answer as not exactly answering the question? -- Rick Block (talk) 21:09, 9 May 2010 (UTC)

- Now one for you Rick How many sources criticise the one source that started all this nonsense? Martin Hogbin (talk) 15:53, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- I think you have this exactly backwards. Vos Savant is the primary source presenting an unconditional solution completely ignoring the conditional answer. There are many (I doubt that it's hundreds) of reliable sources (mostly non-academic, which doesn't necessarily mean they're not reliable) that follow HER lead. I think there are at least as many sources that present a conditional solution - and these tend to be academic and peer reviewed sources which (per WP:SOURCES) "are usually the most reliable sources where available". The number of sources criticizing sources presenting an unconditional solution is perhaps a dozen or so (PLENTY enough to call it a significant POV), and indeed Morgan et al. was the first but most of the rest are actually independent. For example, there's clearly no way Gillman is based on Morgan et al. As far as how many sources criticize Morgan et al., I think the answer may be two - Seymann's comment and Rosenhouse's book - although both of these are essentially criticizing the tone, not the mathematics. I think you are missing the fact that vos Savant's POV being the most popular among lay people (which, of course it is, since she was writing for an extremely widely distributed medium) does not in any way mean it is the most prevalent among published sources. The question is not how many people hold a particular POV, but how many sources do - and, if sources disagree, the relative reliability of those sources comes into play as well. -- Rick Block (talk) 17:09, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Seymann was not criticising the tone of Morgan's paper he was suggesting that Morgan had answered the wrong question or at the very least failed to realise that the question could have been read in more than one way. That must seriously lower Morgan's credibility as a peer reviewed source. Martin Hogbin (talk) 19:22, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- I think you have this exactly backwards. Vos Savant is the primary source presenting an unconditional solution completely ignoring the conditional answer. There are many (I doubt that it's hundreds) of reliable sources (mostly non-academic, which doesn't necessarily mean they're not reliable) that follow HER lead. I think there are at least as many sources that present a conditional solution - and these tend to be academic and peer reviewed sources which (per WP:SOURCES) "are usually the most reliable sources where available". The number of sources criticizing sources presenting an unconditional solution is perhaps a dozen or so (PLENTY enough to call it a significant POV), and indeed Morgan et al. was the first but most of the rest are actually independent. For example, there's clearly no way Gillman is based on Morgan et al. As far as how many sources criticize Morgan et al., I think the answer may be two - Seymann's comment and Rosenhouse's book - although both of these are essentially criticizing the tone, not the mathematics. I think you are missing the fact that vos Savant's POV being the most popular among lay people (which, of course it is, since she was writing for an extremely widely distributed medium) does not in any way mean it is the most prevalent among published sources. The question is not how many people hold a particular POV, but how many sources do - and, if sources disagree, the relative reliability of those sources comes into play as well. -- Rick Block (talk) 17:09, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

Wikipedia's Standards Are Higher Than The American Statistician's

Rick keeps asking Martin 'How many sources...?'

But it's a bogus question.

In Morgan's paper, they appear ignorant of Selvin's letters. By their 'standard', 1 source, even the 'original' is not enough. They just act as if it didn't exist. Even though the letters were published in the exact same journal! Who died and made them boss?

So, like a junkyard dog with nothing else to 'protect' (no more 'host bias' argument, no more 'disputed State of Knowledge, no more 'simple solution is wrong') Rick accuses anyone of proposing changes that do not follow his PERSONAL INTERPRETATION of the published material as violating the sacrosanct Wikipedia NPOV pillar.

Did anyone see that most recent edit to the article? The diff shows, I believe, Line 28 after the edit. Perhaps the worst written English sentence I have ever read. Glkanter (talk) 12:43, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Um, what are you talking about - this diff? And, I'm asking for sources, not personal opinions. -- Rick Block (talk) 14:36, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- No, not any edit you made, Rick. Some other editor, just yesterday maybe, added a period to a sentence. The diff showed the next paragraph, or at least a sentence. It's just horrible. Sorry for the confusion. Glkanter (talk) 15:39, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- Just as a break for mediator from this article will help him become refocussed and reenergised, so too would a break for the parties to this dispute be beneficial. Unless of course you feel that the discussions that are today taking place on this talk page are beneficial, in which case please do proceed. AGK 19:30, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- We had a clear consensus of editors last November. That's when Rick resorted to his 'NPOV' complaint.

- To suggest anyone needs to calm down after weeks of silence is preposterous. Glkanter

- No, we did not have a "clear consensus". Even with a totally skewed methodology counting "for change" vs. "keep as is", the count (which does not determine consensus) was what 8-5?. And what I've actually said is consensus cannot overrule NPOV - so even if there were a clear consensus (and, again, there wasn't) the article cannot be written in a way that it fails to represent "fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias, all significant views that have been published by reliable sources". -- Rick Block (talk) 21:15, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- The NPOV argument is somewhat bogus as each side considers the other to be pushing their POV. Also, as Glkanter points out, we have just taken a long break from our discussion, in the hopes that the mediation might achieve something. 21:32, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- No, we did not have a "clear consensus". Even with a totally skewed methodology counting "for change" vs. "keep as is", the count (which does not determine consensus) was what 8-5?. And what I've actually said is consensus cannot overrule NPOV - so even if there were a clear consensus (and, again, there wasn't) the article cannot be written in a way that it fails to represent "fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias, all significant views that have been published by reliable sources". -- Rick Block (talk) 21:15, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Well, let's see. "Your side" has been complaining about bias for the Morgan et al. POV since about this version (the version following the last FAR) which presents a simple solution, and then transitions to a conditional solution with two paragraphs in between that say

- The reasoning above applies to all players at the start of the game without regard to which door the host opens, specifically before the host opens a particular door and gives the player the option to switch doors (Morgan et al. 1991). This means if a large number of players randomly choose whether to stay or switch, then approximately 1/3 of those choosing to stay with the initial selection and 2/3 of those choosing to switch would win the car. This result has been verified experimentally using computer and other simulation techniques (see Simulation below).

- A subtly different question is which strategy is best for an individual player after being shown a particular open door. Answering this question requires determining the conditional probability of winning by switching, given which door the host opens. This probability may differ from the overall probability of winning depending on the exact formulation of the problem (see Sources of confusion, below).

- The article now looks like this, with completely separate sections for simple solutions and conditional solutions, with nothing at all in the simple solution section contradicting it or in any way saying it is deficient (hmmm, much like what you claim above is your goal) but yet you're STILL complaining about "pro-Morgan" bias. Separate, but equal, solution sections are apparently not good enough for you and you want more. Glkanter has never exactly said what he wants, but apparently wants to delete all references to Morgan et al. You say you're OK with simply moving any mention of conditional probability to a later section of the article (burying it, in newspaper terminology). This is the point at which I have been pushing back on NPOV grounds. If the two of you are not simply pushing your POV you're doing a damn good imitation of it. -- Rick Block (talk) 22:16, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- This is not a newspaper article it is a encyclopedia article and using terms like 'burying' to describe putting more complex solutions after simple solutions is completely inappropriate. I can only restate that in many mathematical and technical text books it is common to start with a simplified (and therefore incomplete) version of the subject and then proceed to a address more complex issues. In fact study of most subjects is only possible using this approach. Much school mechanics is based on massless inextensible strings operating over frictionless pulleys, all non-existent entities. Whole books at an advanced level are written on Newtonian mechanics even though, in the light of relativity and quantum mechanics, this is known to be wrong. Even if I liked the Morgan paper and agreed with you that the problem must only be treated conditionally I would still recommend starting with the simple version of the problem, followed immediately with sufficient discussion to ensure that this had been fully understood before proceeding to the conditional case, simply because of the astounding difficulty most people have in understanding and accepting the correct solution. Martin Hogbin (talk) 22:39, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- The article now looks like this, with completely separate sections for simple solutions and conditional solutions, with nothing at all in the simple solution section contradicting it or in any way saying it is deficient (hmmm, much like what you claim above is your goal) but yet you're STILL complaining about "pro-Morgan" bias. Separate, but equal, solution sections are apparently not good enough for you and you want more. Glkanter has never exactly said what he wants, but apparently wants to delete all references to Morgan et al. You say you're OK with simply moving any mention of conditional probability to a later section of the article (burying it, in newspaper terminology). This is the point at which I have been pushing back on NPOV grounds. If the two of you are not simply pushing your POV you're doing a damn good imitation of it. -- Rick Block (talk) 22:16, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Martin - how is this not exactly the structure of the solution section I've proposed? Are you so accustomed to arguing with me you think need to argue with whatever I suggest without even reading it? Again, the suggestion is in this thread. Except for the fact that you're still arguing with me it sounds like we're agreeing. -- Rick Block (talk) 23:44, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Not quite. Your rewritten solution makes the distinction between various (effectively equivalent in my opinion) cases in which: any door is chosen by the player, door 1 is chosen by the player, door 1 is chosen by the player, and door 3 is opened by the host. My suggestion was to keep the same wording that we currently have but move one section to a different place.

- The crux of my suggestion is to keep all complicating issues (which doors are opened, whether the problem is conditional or not) right out of the way until the simple solution has been fully explained and discussed. This does mean initially giving solutions that some might consider to be incomplete to start with, but his is how most text books work. Martin Hogbin (talk) 10:27, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- But doesn't "fully explaining" the simple solution involve explaining exactly which of these situations the solution directly addresses and then (potentially) why it can be considered to also addresses the others? Per K&W, most people think about the specific case where the player's picked door 1 and the host has opened door 3, and have a very hard time switching to the mental model required for the simple solutions to make sense. I'm making the model behind each solution explicit, so however you're thinking of the problem you'll find a matching solution. Not only does this make the presentation of the solutions more NPOV, but (IMO) it helps our readers by providing a solution matching the mental model in which they're trying to solve the problem. -- Rick Block (talk) 13:34, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- I am in favour of anything which helps our readers to understand why the answer is 2/3 and not 1/2 but your suggestion does not, in my opinion, do this. It has three sections, with rather complicated headings, and it is not clear whether these are intended to relate to the same puzzle or different ones. Also the first two sections have confusing disclaimers at the end. I understand why you do this, you want to ensure that what you say is strictly correct but I would say that we should forget all about pedantry in the first section and completely ignore the distinction between the conditional and unconditional cases and the door numbers chosen by the host and the player. We all know that these make no difference to the answer in the standard case and there are plenty of reliable sources that take this approach.

- One the reader has got to grips with the main problem, and if they are interested, they can read about Morgans criticism of the simple solutions, read about Morgan's solution and read about conditional probability and its effect on the solution if the host is considered to choose non-uniformly. Martin Hogbin (talk) 14:46, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- But doesn't "fully explaining" the simple solution involve explaining exactly which of these situations the solution directly addresses and then (potentially) why it can be considered to also addresses the others? Per K&W, most people think about the specific case where the player's picked door 1 and the host has opened door 3, and have a very hard time switching to the mental model required for the simple solutions to make sense. I'm making the model behind each solution explicit, so however you're thinking of the problem you'll find a matching solution. Not only does this make the presentation of the solutions more NPOV, but (IMO) it helps our readers by providing a solution matching the mental model in which they're trying to solve the problem. -- Rick Block (talk) 13:34, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- Martin - what K&W are saying (and I agree) is that the "simple" solution is very hard to understand if you start with a mental model of 2 closed doors and an open door. You seem to be saying that the article should more or less force the reader to see the problem unconditionally (as if this is the "right" way to understand the problem), and then present a conditional solution later. I'm suggesting we present solutions that match however the reader is thinking about the problem (including looking at 2 doors and an open door) - without forcing a shift between mental models. Not only do I suspect this would be easier to comprehend, but in addition this structure doesn't make the article inherently endorse one view over another (makes it more NPOV). The intent is the solutions all pertain to the same problem - if this is not clear we should work on clarifying it.

- Rick, can we please forget about the distinction between the conditional and unconditional case just for the moment. What I am saying is that I want to start with explanations that are as simple as possible for people to understand and, whatever these explanations are, I do not want to confuse the reader further at that stage with statements that this or that solution is conditional/unconditional or that a given solution is incomplete or does not answer the question. To put it bluntly I would be happy to present an unconditional solution as a solution to the conditional problem. Hardly anybody makes the distinction initially. If the K&W paper helps us to present a convincing solution that is fine with me. Martin Hogbin (talk) 22:01, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- Martin - what K&W are saying (and I agree) is that the "simple" solution is very hard to understand if you start with a mental model of 2 closed doors and an open door. You seem to be saying that the article should more or less force the reader to see the problem unconditionally (as if this is the "right" way to understand the problem), and then present a conditional solution later. I'm suggesting we present solutions that match however the reader is thinking about the problem (including looking at 2 doors and an open door) - without forcing a shift between mental models. Not only do I suspect this would be easier to comprehend, but in addition this structure doesn't make the article inherently endorse one view over another (makes it more NPOV). The intent is the solutions all pertain to the same problem - if this is not clear we should work on clarifying it.

- Although I'm more or less awaiting the result of the mediation, I now and then look at the "progress" made here. @Martin: To put it bluntly, I will not accept a, what you call, unconditional solution to the conditional problem. Nijdam (talk) 10:13, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

- "...I will not accept..." Very sad. Glkanter (talk) 11:57, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

- My bad. I was not previously aware of this little known Wikipedia codicil: WP:NIJDAMISTHEULTIMATEWIKIPEDIADECISIONMAKER. Glkanter (talk) 15:50, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

- How is the "simplest approach" in my suggested solution section not exactly this? Do you think it's not wordy enough to be convincing? What, exactly, would you add? Similarly the enumeration of cases where the player has picked door 1. This is exactly the same as vos Savant's approach. Neither says anything about the distinction between conditional and unconditional (why do you think I'm stuck on this?). These solutions are both complete and (I'd bet) easier to understand than the mess that's currently in the "Popular solution" section of the article. Is what you don't like only that they're immediately followed by a conditional solution? This is how NPOV works. -- Rick Block (talk) 06:50, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

- The disclaimers you're saying are confusing are the numeric samples (right?), for example the first one which says "What this solution is saying is that if 900 contestants all switch, regardless of which door they initially pick and which door the host opens about 600 would win the car.". These are intended to clarify what the associated solution is actually saying - to help match the mental model. At least some people have an easier time thinking about how many times something might happen than probabilities (even though these are fundamentally exactly the same) - i.e. if I roll a die it should be a 2 or a 5 roughly two times out of every six rolls (as opposed to "with probability 1/3"). Do you personally find these confusing are you saying you think others might? -- Rick Block (talk) 19:21, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- Once again you seem stuck on the conditional/unconditional issue. Pretty well nobody who sees the problem for the first time is aware of the potential difference between the player choosing before the host has opened a door and the player choosing afterwords, thus there is no need to match mental models as you put it. The fact that we seem to make a distinction between a player winning 200 times out of 300 and a player having a probability of winning of 2/3 serves only to confuse. Martin Hogbin (talk) 22:01, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- The disclaimers you're saying are confusing are the numeric samples (right?), for example the first one which says "What this solution is saying is that if 900 contestants all switch, regardless of which door they initially pick and which door the host opens about 600 would win the car.". These are intended to clarify what the associated solution is actually saying - to help match the mental model. At least some people have an easier time thinking about how many times something might happen than probabilities (even though these are fundamentally exactly the same) - i.e. if I roll a die it should be a 2 or a 5 roughly two times out of every six rolls (as opposed to "with probability 1/3"). Do you personally find these confusing are you saying you think others might? -- Rick Block (talk) 19:21, 11 May 2010 (UTC)

- Martin - The bottom line is there are multiple reliable sources that present only a conditional solution (I've found 14 so far - these are published papers and books - and haven't spent much time looking), and multiple sources that explicitly criticize "simple" solutions. Wikipedia policy says the views of these sources must be represented "fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias" (regardless of whether you agree with them). I'd honestly prefer if we could agree that presenting both approaches in an integrated fashion is actually more helpful to our readers, but whether you agree or not I think ultimately NPOV will drive us to this structure. IMO, what you're suggesting is not NPOV. If you don't think what I'm suggesting is NPOV or easy enough to understand, please suggest another alternative. -- Rick Block (talk) 06:50, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

- Rick and Nijdam, you have both completely missed my point. I will explain in a section below. Martin Hogbin (talk) 12:46, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

- Martin - The bottom line is there are multiple reliable sources that present only a conditional solution (I've found 14 so far - these are published papers and books - and haven't spent much time looking), and multiple sources that explicitly criticize "simple" solutions. Wikipedia policy says the views of these sources must be represented "fairly, proportionately, and as far as possible without bias" (regardless of whether you agree with them). I'd honestly prefer if we could agree that presenting both approaches in an integrated fashion is actually more helpful to our readers, but whether you agree or not I think ultimately NPOV will drive us to this structure. IMO, what you're suggesting is not NPOV. If you don't think what I'm suggesting is NPOV or easy enough to understand, please suggest another alternative. -- Rick Block (talk) 06:50, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

- Glkanter: From the completely unproductive nature of this conversation even since my comment, it seems that my suggestion was far from preposterous. The positions in this debate are irreconcilable, at least without outside assistance from a mediator or some other facilitating party; and so further interaction is at best useless and at worst conducive to bickering. YMMV. AGK 22:21, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- Very simply, Wikipedia seems to have no mechanism for resolving this long-running (5 years?) dispute. Dragging out this 'mediation' may have lessened the activity, but has done nothing to move this closer to a resolution of the underlying issues. Glkanter (talk) 22:38, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- AKG, I think we once came very close to a solution, which was my suggestion to simply swap the order of two sections in the article, as suggested in remarks above. This would not completely resolve all the problems but it would have meant that we could probably all work much better together to improve the article. This was stalled by one, or maybe two, editors. Martin Hogbin (talk) 22:58, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

- And, we've come equally close (actually closer, since nearly final wording is available) with the merged solution section that I've proposed, that has been stalled by you and Glkanter. -- Rick Block (talk) 23:31, 10 May 2010 (UTC)

A genuine attempt at compromise.

My POV is the Morgan paper is no more that a minor academic distraction from the real MHP, which is a mathematical puzzle in which the host is defined to open a legal door randomly and the issue of conditional probability is insignificant. However, in the interests of compromise, I will put this view to one side and adopt the position that conditional probability and, in particular, the host's choice of door when the player has originally chosen the car, is essential to a proper understanding of the problem. I will also accept that this view is fully supported by a multitude of reliable sources.

The question now becomes, 'How do we explain this position to our readers?'. I suggest that we should follow the model of many mathematical and technical text books and, bearing in mind how hard most people find any version of this problem when they first see it, start with a simplified (and possible strictly incorrect) solution and explanation of the problem. Note carefully that I am not suggesting that we start with a unconditional formulation of the problem because, even mention of the two possibilities that the player chooses after the host has opened a door or before he has done so, adds another layer of conceptual complication to the problem. What I am suggesting is that we ignore this point completely to start with. Nobody at first sight finds the legal door opened by the host to be significant.

Again, I draw the parallel with text books. Mathematicians can be as rigorous and pedantic as you like when they put their minds to it but if they adopted this approach in books on most mathematical topics the intended readers would not get beyond the first page before giving up. Strictly speaking, Newtonian physics is wrong, but it is still taught in all schools and colleges. I am not against trying to use the K&W paper to help us or trying to keep the errors and omissions to a minimum, but not at the expense of clarity. Let me add that many books have a page of problems after the first introductory chapter to ensure that the reader has understood so far. We should do similarly and have a 'Aids to understanding' section before discussing complicating issues.

Now you may see this as a dirty trick to get my own way by subterfuge but actually it is a way that works for everybody. We have what is undoubtedly one of the world's most difficult simple puzzles, which even famous mathematicians have got wrong. Do we really want to start our article by making the problem harder? Martin Hogbin (talk) 13:34, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

- And my genuine attempt at a compromise is the following proposal which I think satisfies what you're suggesting (other than the "aids to understanding" - more on this below). It starts with two simplified explanations of the solution to the problem, both ignoring a precise definition of the problem, almost exactly like the presentation in Grinstead and Snell (a textbook). It doesn't say these simplified explanations are wrong, but it does attempt to say what it is that they actually say. Is this what you object to about this proposal?

- Why I object to putting the "aids to understanding" section between the simple solutions and the conditional solution is that it implies, by the structure of the article (see WP:STRUCTURE), that the "simple" solutions are correct and undisputed. You say you're willing to put your POV aside and "adopt the position that conditional probability and, in particular, the host's choice of door when the player has originally chosen the car, is essential to a proper understanding of the problem" - but then what you're suggesting doesn't do this. Instead, it puts the simple solutions and the conditional solution on unequal footing, separated by a lengthy "aids to understanding" section. Unless the "other" view is contextually nearby, whatever view is presented first (more or less) becomes the de facto view of the article. This is apparently a common enough POV issue that it's even mentioned in the NPOV policy page. You might think I'm raising NPOV as a dirty trick to get my way - but I'm already not getting my way (my actual preference would be to start with a conditional solution and put all the simple solutions in "aids to understanding"). Treating this as a POV issue seems to me like the most reasonable compromise.

- I understand your concern about the understandability of the simple solutions, but I think it is misplaced. No one fails to understand what these solutions literally say. What people fail to understand is how these solutions connect to their mental image of picking door 1 and then standing in front of two closed doors after the host has opened door 3. The fact is the simple solutions simply do not address this case (but the conditional solution does

), i.e. it's not understanding these solutions that's difficult, it's mentally redefining the problem so these solutions apply (specifically that the overall chance of winning by switching, which the simple solutions clearly show is 2/3, must be the same as the chance in any individual case). So, again, my suggested compromise is we present both kinds of solutions, as neutrally as we can manage, but immediately adjacent. My strong preference is to have them in a single "Solution" section, like below. This is changed slightly from the previous version in an attempt to connect the simple solutions to the mental image most people create based on the problem description. -- Rick Block (talk) 16:25, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

), i.e. it's not understanding these solutions that's difficult, it's mentally redefining the problem so these solutions apply (specifically that the overall chance of winning by switching, which the simple solutions clearly show is 2/3, must be the same as the chance in any individual case). So, again, my suggested compromise is we present both kinds of solutions, as neutrally as we can manage, but immediately adjacent. My strong preference is to have them in a single "Solution" section, like below. This is changed slightly from the previous version in an attempt to connect the simple solutions to the mental image most people create based on the problem description. -- Rick Block (talk) 16:25, 12 May 2010 (UTC)

Proposed text

| ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|