Heart transplantation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

* [http://www.medicalvideos.us/videos-2062-Heart-Transplant-Video Orthotopic Heart Transplant Video] |

* [http://www.medicalvideos.us/videos-2062-Heart-Transplant-Video Orthotopic Heart Transplant Video] |

||

* [http://www.umc.edu/about_us/hardy.html University of Mississippi Medical Center] |

* [http://www.umc.edu/about_us/hardy.html University of Mississippi Medical Center] |

||

* [http://www.heartpatients.org/page/heart-transplant-patient-guide Patient's Guide to Heart Transplant Surgery] |

|||

* [http://www.childrens.com/Specialties/template.cfm?groupid=2&pageid=46 Heart Transplant at Children's Medical Center] |

* [http://www.childrens.com/Specialties/template.cfm?groupid=2&pageid=46 Heart Transplant at Children's Medical Center] |

||

*[http://www.heartofcapetown.co.za Official Heart Transplant Museum - Heart Of Cape Town] |

*[http://www.heartofcapetown.co.za Official Heart Transplant Museum - Heart Of Cape Town] |

||

Revision as of 13:07, 27 August 2010

Hearts transplants, or cardiac transplantation, is a surgical transplant procedure performed on patients with end-stage heart failure or severe coronary artery disease. The most common procedure is to take a working heart from a recently deceased organ donor (allograft) and implant it into the patient. The patient's own heart may either be removed (orthotopic procedure) or, less commonly, left in to support the donor heart (heterotopic procedure); both are controversial solutions to one of the most enduring human ailments. Post-operation survival periods now average 15 years.[1]

The world's first human heart transplant was performed by Christiaan Barnard on December 3, 1967 in Cape Town South Africa.[2] Worldwide there are 3,500 heart transplants performed every year; about 800,000 people have a Class IV heart defect and need a new organ.[3] This disparity has spurred considerable research into the use of non-human hearts since 1993. It is now possible to take a heart from another species (xenograft), or implant a man-made artificial one, although the outcome of these two procedures has been less successful in comparison to the far more commonly performed allografts. Engineers want to fix the remaining problems with the manufactured options in the next 15 years.[1]

Contradications

Some patients are less suitable for a heart transplant, especially if they suffer from other circulatory conditions unrelated to the heart. The following conditions in a patient would increase the chances of complications occurring during the operation:

- Kidney, lung, or liver disease

- Insulin-dependent diabetes with other organ dysfunction

- Life-threatening diseases unrelated to heart failure

- Vascular disease of the neck and leg arteries.

- High pulmonary vascular resistance

- Recent thromboembolism

- Age over 60 years (some variation between centres)

- Alcohol, tobacco or drug abuse

Procedures

Pre-operative

A typical heart transplantation begins with a suitable donor heart being located from a recently deceased or brain dead donor, also called a beating heart cadaver. The transplant patient is contacted by a nurse coordinator and instructed to attend the hospital in order to be evaluated for the operation and given pre-surgical medication. At the same time, the heart is removed from the donor and inspected by a team of surgeons to see if it is in a suitable condition to be transplanted. Occasionally it will be deemed unsuitable. This can often be a very distressing experience for an already emotionally unstable patient, and they will usually require emotional support before being sent home. The patient must also undergo many emotional, psychological, and physical tests to make sure that they are in good mental health and will make good use of their new heart. The patient is also given immunosuppressant medication so that their immune system will not reject the new heart.

Operative

Once the donor heart has passed its inspection, the patient is taken into the operating room and given a general anesthetic. Either an orthotopic or a heterotopic procedure is followed, depending on the condition of the patient and the donor heart.

Orthotopic procedure

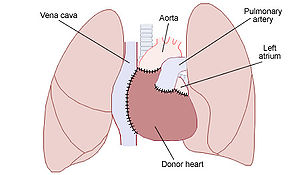

The orthotopic procedure begins with the surgeons performing a median sternotomy to expose the mediastinum. The pericardium is opened, the great vessels are dissected and the patient is attached to cardiopulmonary bypass. The failing heart is removed by transecting the great vessels and a portion of the left atrium. The pulmonary veins are not transected; rather a circular portion of the left atrium containing the pulmonary veins is left in place. The donor heart is trimmed to fit onto the patient's remaining left atrium and the great vessels are sutured in place. The new heart is restarted, the patient is weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass and the chest cavity is closed.

Heterotopic procedure

In the heterotopic procedure, the patient's own heart is not removed before implanting the donor heart. The new heart is positioned so that the chambers and blood vessels of both hearts can be connected to form what is effectively a 'double heart'. The procedure can give the patients original heart a chance to recover, and if the donor's heart happens to fail (e.g. through rejection), it may be removed, allowing the patient's original heart to start working again. Heterotopic procedures are only used in cases where the donor heart is not strong enough to function by itself (due to either the patient's body being considerably larger than the donor's, the donor having a weak heart, or the patient suffering from pulmonary hypertension).

Post-operative

The patient is taken into ICU to recover. When they wake up, they will be transferred to a special recovery unit in order to be rehabilitated. How long they remain in hospital post-transplant depends on the patient's general health, how well the new heart is working, and their ability to look after their new heart. Doctors typically like the new recipients to leave hospitals soon after surgery because of the risk of infection in a hospital (typically 1 – 2 weeks without any complications). Once the patient is released, they will have to return to the hospital for regular check-ups and rehabilitation sessions. They may also require emotional support. The number of visits to the hospital will decrease over time, as the patient adjusts to their transplant. The patient will have to remain on lifetime immunosuppressant medication to avoid the possibility of rejection. Since the vagus nerve is severed during the operation, the new heart will beat at around 100 bpm until nerve regrowth occurs.

'Living organ' transplant

Doctors made medical history in February 2006, at Bad Oeynhausen Clinic for Thorax- and Cardiovascular Surgery, Germany, when they successfully transplanted a 'beating heart' into a patient.[4] Normally a donor's heart is injected with potassium chloride in order to stop it beating, before being removed from the donor's body and packed in ice in order to preserve it. The ice can usually keep the heart fresh for a maximum of four[5] to six hours with proper preservation, depending on its starting condition. Rather than cooling the heart, this new procedure involves keeping it at body temperature and hooking it up to a special machine called an Organ Care System that allows it to continue beating with warm, oxygenated blood flowing through it. This can maintain the heart in a suitable condition for much longer than the traditional method.

Complications

Post-operative complications include infection, sepsis, organ rejection, as well as the side-effects of the immunosupressive medication. Since the transplanted heart originates from another organism, the recipient's immune system may attempt to reject it. Immunosupressive drugs reduce that risk, but may have some unwanted side effects, such as increased likelihood of infections or nephrotoxic effects.

Prognosis

The prognosis for heart transplant patients following the orthotopic procedure has greatly increased over the past 20 years, and as of June 5, 2009, the survival rates were as follows.[6]

- 1 year: 88% (males), 77,2% (females)

- 3 years: 79,3% (males), 77.2% (females)

- 5 years: 73,1% (males), 67.4% (females)

In a November 2008 study conducted on behalf of the U.S. federal government by Dr. Eric Weiss of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, it was discovered that heart transplants — all other factors being accounted for — work better in same-sex transplants (male to male, female to female). However, due to the present acute shortage in donor hearts, this may not always be feasible.

As of August 2009, Tony Huesman was the world's longest living heart transplant recipient, having survived for 31 years with a transplanted heart. Huesman received a heart in 1978 at the age of 20 after viral pneumonia severely weakened his heart. Huesman died on August 10, 2009 of cancer.[7] The operation was performed at Stanford University under American heart transplant pioneer Dr. Norman Shumway, who continued to perform the operation in the U.S. after others abandoned it due to poor results[8]. Another noted heart transplant recipient, Kelly Perkins, climbs mountains around the world to promote positive awareness of organ donation. Perkins is the first heart transplant recipient to climb to the peaks of Mt. Fuji, Mt. Kilimanjaro, the Matterhorn, Mt. Whitney, and Cajon de Arenales in Argentina in 2007, 12 years after her transplant surgery. Dwight Kroening is yet another noted recipient promoting positive awareness for organ donation. Twenty two years after his heart transplant, he is the first to finish an Ironman competition.[9] Fiona Coote was the second Australian to receive a heart transplant in 1984 (at age 14) and the youngest Australian. At 24 years since her transplant she is also a long term survivor and is involved in publicity and charity work for the red cross, and promoting organ donation in Australia.

See also

References

- ^ a b Till Lehmann (director) (2007). The Heart-Makers: The Future of Transplant Medicine (documentary film). Germany: LOOKS film and television.

- ^ "Memories of the Heart". Doylestown, Pennsylvania: Daily Intelligencer. November 29, 1987. p. A-18.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Reiner Körfer (interviewee) (2007). The Heart-Makers: The Future of Transplant Medicine (documentary film). Germany: LOOKS film and television.

- ^ "Bad Oeynhausen Clinic for Thorax- and Cardiovascular Surgery Announces First Successful Beating Human Heart Transplant". TransMedics. 23 February 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- ^ Custodiol Htk Solution patient advice including side effects

- ^ Heart Transplants: Statistics The American Heart Association. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ http://www.columbusdispatch.com/live/content/local_news/stories/2009/08/10/aheart.html?sid=101

- ^ Heart Transplant Patient OK After 28 Yrs (14 September 2006) CBS News. Retrieved 29 December 2006.

- ^ Dwight Kroening first heart transplant to do ironman Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- Western Cape government, South Africa (21 February 2005). "Chris Barnard Performs World's First Heart Transplant". Cape Gateway. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery. "Patient's Guide to Heart Transplant Surgery". University of Southern California. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- Nancy Reid (22 September 2005). "Heart transplant: How is it performed?". Healthwise. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- Jeffrey Everett (2003-10-29). "Heart Transplant: Indications". AllRefer.com. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- "Hartford Hospital Heart Transplant Program". Hartford Hospital, Connecticut, United States. Retrieved 2007-01-10.

External links

- Orthotopic Heart Transplant Video

- University of Mississippi Medical Center

- Patient's Guide to Heart Transplant Surgery

- Heart Transplant at Children's Medical Center

- Official Heart Transplant Museum - Heart Of Cape Town

- Photograph of first U.S. heart transplant

- British Heart Foundation - Information on Heart Transplants