Joseph Pulitzer: Difference between revisions

+net worth |

→New York World: Added citation. |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

[[Charles A. Dana]], the editor of the rival ''[[New York Sun (historical)|New York Sun]]'' attacked Pulitzer in print, often using anti-semitic terms like "Judas Pulitzer".<ref>Brian (2001) p. 129</ref> |

[[Charles A. Dana]], the editor of the rival ''[[New York Sun (historical)|New York Sun]]'' attacked Pulitzer in print, often using anti-semitic terms like "Judas Pulitzer".<ref>Brian (2001) p. 129</ref> |

||

In 1895, [[William Randolph Hearst]] purchased the rival ''[[New York Journal]]'' from Pulitzer's brother, Albert, which led to a circulation war. This competition with Hearst, particularly the coverage before and during the [[Spanish-American War]], linked Pulitzer's name with [[yellow journalism]]. |

In 1895, [[William Randolph Hearst]] purchased the rival ''[[New York Journal]]'' from Pulitzer's brother, Albert, which led to a circulation war. This competition with Hearst, particularly the coverage before and during the [[Spanish-American War]], linked Pulitzer's name with [[yellow journalism]].<ref>Buescher, John. "[http://www.teachinghistory.org/history-content/ask-a-historian/22927 Breaking the News in 1900]." [http://www.teachinghistory.org Teachinghistory.org], accessed 2 September, 2011.</ref> |

||

Pulitzer had an uncanny knack for appealing to the common man. His ''World'' featured illustrations, advertising, and a culture of consumption for working men who, Pulitzer believed, saved money to enjoy life with their families when they could, at Coney Island for example.<ref>J.E.. Steele, "The 19th Century World Versus the Sun: Promoting Consumption (Rather than the Working Man)," ''Journalism Quarterly,'' Autumn 1990, Vol. 67 Issue 3, pp 592–600</ref> Crusades for reform and news of entertainment were the two main staples for the 'World.' Before the demise of the paper in 1931, many of the best reporters in America worked for it. |

Pulitzer had an uncanny knack for appealing to the common man. His ''World'' featured illustrations, advertising, and a culture of consumption for working men who, Pulitzer believed, saved money to enjoy life with their families when they could, at Coney Island for example.<ref>J.E.. Steele, "The 19th Century World Versus the Sun: Promoting Consumption (Rather than the Working Man)," ''Journalism Quarterly,'' Autumn 1990, Vol. 67 Issue 3, pp 592–600</ref> Crusades for reform and news of entertainment were the two main staples for the 'World.' Before the demise of the paper in 1931, many of the best reporters in America worked for it. |

||

Revision as of 19:38, 2 September 2011

There is not a crime, there is not a dodge, there is not a trick, there is not a swindle, there is not a vice which does not live by secrecy. Get these things out in the open, describe them, attack them, ridicule them in the press, and sooner or later public opinion will sweep them away. Publicity may not be the only thing that is needed, but it is the one thing without which all other agencies will fail.

Joseph Pulitzer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 9th district | |

| In office March 4, 1885 – April 10, 1886 | |

| Preceded by | John Hardy |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Cox |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 10, 1847 Makó, Hungary |

| Died | October 29, 1911 (aged 64) Charleston, South Carolina, U.S.A. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Occupation | Publisher, philanthropist, journalist, lawyer |

| Net worth | USD $30 million at the time of his death (approximately 1/1142nd of US GNP)[1] |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Union Army |

| Years of service | 1864–1865 |

| Unit | First Regiment, New York Cavalry |

| Battles/wars | Civil War |

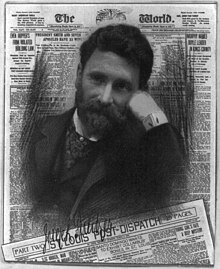

Joseph Pulitzer (/[invalid input: 'icon'][invalid input: 'En-us-Pulitzer.ogg']ˈpʊl[invalid input: 'ɨ']tsər/ PUUL-it-sər;[2] April 10, 1847 – October 29, 1911), born Politzer József, was a Hungarian-American newspaper publisher of the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the New York World. Pulitzer introduced the techniques of "new journalism" to the newspapers he acquired in the 1880s and became a leading national figure in the Democratic party. He crusaded against big business and corruption. In the 1890s the fierce competition between his World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal introduced yellow journalism and opened the way to mass circulation newspapers that depended on advertising revenue and appealed to the reader with multiple forms of news, entertainment and advertising.

Today he is best known for posthumously establishing the Pulitzer Prizes.

Early life

The first Pulitzers emigrated from Moravia to Hungary at the end of the 18th century. Joseph Pulitzer's native town was Makó, about 200 kilometers southeast of Budapest. The Pulitzers were among several Jewish families living in the area, and had established a reputation as merchants and shopkeepers. Joseph's father, Fülöp Pulitzer, was a respected businessman and was regarded as the "foremost merchant" of Makó. In 1853, Philip was rich enough to retire and move his family to Budapest, where the children were educated by private tutors and learned French and German. However, in 1858, after Fülöp's death, his business went bankrupt and the family became impoverished. Joseph attempted to enlist in various European armies before he finally emigrated to America.[3]

Arriving in New York in 1864, he enlisted in the Lincoln Cavalry on September 30; he was 18. He was a part of Sheridan's troopers, in the First New York Lincoln Cavalry in Company L. He served eight months, and he also spoke three languages: German, Hungarian, and French, and he only knew a little English because his regiment was mostly composed of Germans.[4]

After the war

After the war, he returned to New York City, where he stayed for a short while. He moved to New Bedford for whaling, learned it was moribund, and returned to New York with little money. He was flat broke and sleeping in wagons on cobble stoned side streets. He decided to travel by side-door Pullman to St. Louis, Missouri. He sold his one possession, a white handkerchief, for 75 cents. When he arrived to the city, he recalled "The lights of St. Louis looked like a promise land to me". In the city, German was as useful as it was in Munich. In the Westliche Post, he saw an ad for a mule hostler at Benton Barracks. The next day he walked four miles, got the job, but held it for a mere two days. He quit due to the food and the whims of the mules, stating "The man who has not cared for sixteen mules does not know what work and troubles are".[5] He had difficulty holding jobs; either he was too scrawny for heavy labor or too proud and temperamental to take orders.

One job he held was that of a waiter at Tony Faust's famous restaurant on Fifth Street. This was a place frequented by members of the St. Louis Philosophical Society, including Thomas Davidson, fellow German and nephew of Otto Von Bismarck Henry C. Brockmeyer, and William Torrey Harris. He studied Brockmeyer, who was famous for translating Hegel, and he "would hang on Brockmeyer's thunderous words, even as he served them pretzels and beer". He was soon fired after a tray slipped from his hand and soaked a patron. He would spend his free time at the St. Louis Mercantile Library on the corner of Fifth and Locust, studying English and reading voraciously. Soon after, he and several dozen men each paid a fast-talking promoter five dollars. He promised them well paying jobs on a Louisiana sugar plantation. They boarded a malodorous little steamboat, which took them down river 30 miles south of the city. When the boat churned away, it appeared to them that it was a ruse. They walked back to the city, where Joseph wrote an account of the fraud and was pleased when it was accepted by the Westliche Post, evidently his first published news story.

In the building was the Westliche Post which was co-edited by Dr. Emil Pretorius and Carl Schurz, attorneys William Patrick and Charles Phillip Johnson, and surgeon Joseph Nash McDowell. Patrick and Johnson referred to Pulitzer as "Shakespeare" because of his extraordinary profile. Patrick and Johnson helped him secure another job, this time with the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad.[6]

He rode south to Janesville, Minnesota, where many settlers refused to believe the American Civil War was over. Pulitzer's job was to record the railroad charter in the court houses of the twelve counties it would pass through. When he was done the lawyers gave him desk space and access to their library where Pulitzer studied law. On March 6, 1867, he renounced his allegiance to Austria and became an American citizen. He still frequented the Mercantile Library where he befriended the librarian, Udo Brachvogel, with whom he remained friends for the rest of his life. He was often in the chess room where another player, Carl Schurz, noticed his aggressive game play. Schurz was looked up to by Pulitzer. He was an inspiring emblem of American Democracy, of the success attainable by a foreign-born citizen through his own energies and skills. In 1868, he was admitted to the bar, but his broken English and odd appearance kept clients away. He struggled with the execution of minor papers and the collecting of debts. It wasn't until 1868 when the Westliche Post needed a reporter that he was offered the job.[7]

Newspaper career

Pulitzer displayed a flair for reporting. He would work 16 hours a day—from 10 AM to 2 AM. He was nicknamed "Joey the German" or "Joey the Jew". He joined the Philosophical Society and he frequented a German bookstore where many intellectuals hung out. Among his new repertoire of friends were Joseph Keppler and Thomas Davidson.[8]

He joined the Republican Party. On December 14, 1869, Pulitzer attended the Republican meeting at the St. Louis Turnhalle on Tenth Street, where party leaders needed a candidate to fill a vacancy in the state legislature. They settled on Pulitzer, nominating him unanimously, forgetting he was only 22, three years under the required age. His chief Democratic opponent was of doubtful eligibility because he had served in the Confederate army. Pulitzer had energy. He organized street meetings, called personally on the voters, and exhibited such sincerity along with his oddities that he had pumped a half-amused excitement into a campaign that was normally lethargic. He won 209-147. His age was not made an issue and he was seated as a state representative in Jefferson City at the session beginning January 5, 1870. He had only lived there for two years, an example of quick accomplishment of political power. He also moved him up one notch in the administration at the Westliche Post. He eventually became its managing editor, and obtained a proprietary interest.[9]

In 1872 he was a delegate to the Cincinnati convention of the Liberal Republican Party which nominated Horace Greeley for the presidency. However, the attempt at electing Greeley as president failed, the party collapsed, and Pulitzer, disillusioned with the corruption in the GOP, switched to the Democratic party. In 1880 he was a delegate to the Democratic national convention, and a member of its platform committee from Missouri.[9]

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

In 1872, Pulitzer purchased a share in the Westliche Post for $3,000, and then sold his stake in the paper for a profit in 1873. In 1879 he bought the St. Louis Dispatch, and the St. Louis Post and merged the two papers as the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which remains St. Louis's daily newspaper. It was at the Post-Dispatch that Pulitzer developed his role as a champion of the common man with exposés and a hard-hitting populist approach.[9]

New York World

In 1883, Pulitzer, by then a wealthy man, purchased the New York World, a newspaper that had been losing $40,000 a year, for $346,000 from Jay Gould. Pulitzer shifted its focus to human-interest stories, scandal, and sensationalism. In 1884, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, but resigned after a few months' service on account of the pressure of journalistic duties. In 1887, he recruited the famous investigative journalist Nellie Bly. In 1895 the World introduced the immensely popular The Yellow Kid comic by Richard F. Outcault, the first newspaper comic printed with color. Under Pulitzer's leadership circulation grew from 15,000 to 600,000, making it the largest newspaper in the country.[10]

Charles A. Dana, the editor of the rival New York Sun attacked Pulitzer in print, often using anti-semitic terms like "Judas Pulitzer".[11]

In 1895, William Randolph Hearst purchased the rival New York Journal from Pulitzer's brother, Albert, which led to a circulation war. This competition with Hearst, particularly the coverage before and during the Spanish-American War, linked Pulitzer's name with yellow journalism.[12]

Pulitzer had an uncanny knack for appealing to the common man. His World featured illustrations, advertising, and a culture of consumption for working men who, Pulitzer believed, saved money to enjoy life with their families when they could, at Coney Island for example.[13] Crusades for reform and news of entertainment were the two main staples for the 'World.' Before the demise of the paper in 1931, many of the best reporters in America worked for it.

After the World exposed an illegal payment of $40 million by the United States to the French Panama Canal Company in 1909, Pulitzer was indicted for libeling Theodore Roosevelt and J. P. Morgan. The courts dismissed the indictments.

Editors

Pulitzer's already failing health deteriorated rapidly and he withdrew from the daily management of the newspaper, although he continued to actively manage the paper from his vacation retreat in Bar Harbor, Maine, and his New York mansion.

Frank I. Cobb (1869–1923) was hired as the editor of the New York 'World' in Michigan who resisted Pulitzer's attempts to "run the office" from his home. However hard the elder man might try, he simply could not keep from meddling with Cobb's work. Time after time they battled each other, often with heated language. While they found common ground in their support of Woodrow Wilson as president, they disagreed on many other issues. When Pulitzer's son took over administrative responsibility in 1907, Pulitzer wrote a precisely worded resignation which was printed in every New York paper – except the World. Pulitzer raged at the insult, but slowly began to respect Cobb's editorials and independent spirit. Exchanges, commentaries, and messages between them increased. The good rapport between the two was based largely on Cobb's flexibility. In May 1908, Cobb and Pulitzer met to outline plans for a consistent editorial policy. However, the editorial policy did waver on occasion. Renewed battles broke out over the most trivial matters. Pulitzer's demands for editorials on contemporary breaking news led to overwork by Cobb. Pulitzer revealed concern by sending him on a six-week tour of Europe to restore his spirit. Pulitzer died shortly after Cobb's return; then Cobb published Pulitzer's beautifully written resignation. Cobb retained the editorial policies he had shared with Pulitzer until he died of cancer in 1923.[14]

Once, Professor Thomas Davidson asked of Pulitzer in a company meeting, “I cannot understand why it is, Mr. Pulitzer, that you always speak so kindly of reporters and so severely of all editors.” “Well,” Pulitzer replied, “I suppose it is because every reporter is a hope, and every editor is a disappointment.” This phrase became a famous epigram of journalism.[15]

For a period of six months during 1907, the South African writer, poet and medical doctor, C. Louis Leipoldt, was Pulitzer's personal physician aboard his yacht.

En route to his winter home on Jekyll Island, Georgia, Joseph Pulitzer died aboard his yacht. He is interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York.

Death

Pulitzer died aboard his yacht, the Liberty, in Charleston Harbor, Charleston, South Carolina, on October 29, 1911. [16] He had been sailing for Jekyl Island, Georgia, where he owned a summer home, and his yacht had been in Charleston for five days before his death. His last words came while having his German secretary read to him about King Louis XI of France. As the secretary neared the end of the account, Pulitzer said his last words: "Leise, ganz leise" (English: "Softly, quite softly").

Legacy

Journalism schools

In 1892, Pulitzer offered Columbia University's president, Seth Low, money to set up the world's first school of journalism. The university initially turned down the money, evidently turned off by Pulitzer's odd personality. In 1902, Columbia's new president Nicholas Murray Butler was more receptive to the plan for a school and prizes, but it would not be until after Pulitzer's death that this dream would be fulfilled. Pulitzer left the university $2 million in his will, which led to the creation in 1934 of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, but by then at Pulitzer's urging the Missouri School of Journalism had been created at the University of Missouri. Both schools remain among the most prestigious in the world.

Pulitzer Prize

In 1917, the first Pulitzer Prizes were awarded, in accordance with Pulitzer's wishes. In 1989 Pulitzer was inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame. A fictionalized version of Joseph Pulitzer is portrayed by Robert Duvall in the 1992 Disney film musical, Newsies. He is the main antagonist of that film. There is also a school in Jackson Heights, Queens, New York named after Pulitzer.

See also

- Place des États-Unis

- The Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts

- I.S.145 Joseph Pulitzer middle school in Jackson Heights, Queens, New York City.[17][18][19][20]

References

- ^ Klepper, Michael; Gunther, Michael (1996), The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates—A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present, Secaucus, New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group, p. xiii, ISBN 9780806518008, OCLC 33818143

- ^ "The Pulitzer prizes – Answers to frequently asked questions". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved 2009-08-10.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help). The more anglicized pronunciation /ˈpjuːlɪtsər/ PEW-lit-sər is common but widely considered incorrect. - ^ András Csillag, "Joseph Pulitzer's Roots in Europe: A Genealogical History," American Jewish Archives, Jan 1987, Vol. 39 Issue 1, pp 49–68

- ^ Swanberg, Pulitzer, pp. 3–4

- ^ Swanberg, Pulitzer, pp. 4–5

- ^ Swanberg, Pulitzer, p. 7

- ^ Swanberg, Pulitzer, pp. 7–8

- ^ Swanberg, Pulitzer, p. 10

- ^ a b c Brian (2001)

- ^ Brian, Pulitzer (2001)

- ^ Brian (2001) p. 129

- ^ Buescher, John. "Breaking the News in 1900." Teachinghistory.org, accessed 2 September, 2011.

- ^ J.E.. Steele, "The 19th Century World Versus the Sun: Promoting Consumption (Rather than the Working Man)," Journalism Quarterly, Autumn 1990, Vol. 67 Issue 3, pp 592–600

- ^ Louis M. Starr, "Joseph Pulitzer and his most 'indegoddampendent' editor," American Heritage, June 1968, Vol. 19 Issue 4, pp 18–85

- ^ Popik, Barry. “Every reporter is a hope; every editor is a disappointment”

- ^ Joseph Pulitzer Dies Here, Charleston (S.C.) News & Courier, Oct. 30, 1911, at 1.

- ^ http://www.publicschoolreview.com/school_ov/school_id/56785

- ^ http://insideschools.org/index.php?fs=1247

- ^ http://www.greatschools.org/new-york/jackson-heights/2485-I.S.-145-Joseph-Pulitzer/

- ^ http://www.localschooldirectory.com/public-school/3002443/NY

Further reading

- Brian, Denis. Pulitzer: A Life (2001) online edition

- Morris, James M. Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print and Power (2010), a scholarly biography

- Morris, James McGrath. "The Political Education of Joseph Pulitzer," Missouri Historical Review, Jan 2010, Vol. 104 Issue 2, pp 78–94

- United States Congress. "Joseph Pulitzer (id: P000568)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2008-11-06

- Pfaff, Daniel W. Joseph Pulitzer II and the Post-dispatch (1991)

- Rammelkamp, Julian S. Pulitzer's Post-Dispatch 1878–1883 (1967)

- W.A. Swanberg. Pulitzer (1967) [1], popular

External links

- Original New York World articles at Nellie Bly Online

- NY Times – Harper's Weekly political cartoon American Editors. II.--Joseph Pulitzer; includes in-depth biographical information

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). Encyclopedia Americana.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). "Pulitzer, Joseph". Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- 1847 births

- 1911 deaths

- 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people)

- 19th-century Hungarian people

- Pulitzer family (newspapers)

- American newspaper publishers (people)

- American journalists

- American progressives

- American Jews

- Hungarian journalists

- St. Louis Post-Dispatch people

- Union Army soldiers

- People of the Spanish–American War

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from New York

- Hungarian Jews

- Hungarian people of Czech descent

- Austro-Hungarian Jews

- Austro-Hungarian emigrants to the United States

- American people of Hungarian-Jewish descent

- American people of Hungarian descent

- Jewish members of the United States House of Representatives

- Members of the Missouri House of Representatives

- People from Makó

- People from St. Louis, Missouri

- Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (The Bronx)

- New York Liberal Republicans