Missouri Compromise: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

MR JELLY |

|||

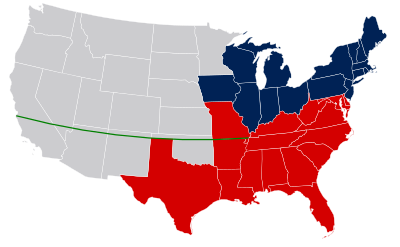

[[Image:USA Territorial Growth 1820 alt.jpg|thumb|300px|The United States in 1819 (the light orange and light green areas were not then part of the United States). The Missouri Compromise prohibited slavery in the [[unorganized territory]] of the Great Plains (upper dark green) and permitted it in Missouri (yellow) and the [[Arkansas Territory]] (lower blue area).]] |

|||

{{Events leading to US Civil War}} |

|||

The ''Missouri Compromise'' was passed in 1820 between the [[slave state|pro-slavery]] and [[Free state (United States)|anti-slavery]] factions in the [[United States Congress]], involving primarily the regulation of [[Slavery in the United States|slavery]] in the [[Historic regions of the United States|western territories]]. It prohibited slavery in the former [[Louisiana Territory]] north of the [[parallel 36°30′ north]] except within the boundaries of the proposed state of [[Missouri]]. The 1820 passage of Missouri Compromise took place during the presidency of [[James Monroe]]. |

|||

The Missouri Compromise was implicitly repealed by the [[Kansas-Nebraska Act]], submitted to [[United States Congress|Congress]] by [[Stephen A. Douglas]] in January 1854. The Act opened [[Kansas Territory]] and [[Nebraska Territory]] to slavery and future admission of slave states by allowing white male settlers in those territories to determine through "[[popular sovereignty]]" whether they would allow slavery within each territory. Thus, the Kansas-Nebraska Act effectively undermined the prohibition on slavery in territory north of 36°30′ latitude which had been established by the Missouri Compromise. This change was viewed by [[Free-Soil Party|Free Soilers]] and many abolitionist Northerners as an aggressive, expansionist maneuver by the slave-owning South, and led to the creation of the [[History of the United States Republican Party|Republican Party]]. |

The Missouri Compromise was implicitly repealed by the [[Kansas-Nebraska Act]], submitted to [[United States Congress|Congress]] by [[Stephen A. Douglas]] in January 1854. The Act opened [[Kansas Territory]] and [[Nebraska Territory]] to slavery and future admission of slave states by allowing white male settlers in those territories to determine through "[[popular sovereignty]]" whether they would allow slavery within each territory. Thus, the Kansas-Nebraska Act effectively undermined the prohibition on slavery in territory north of 36°30′ latitude which had been established by the Missouri Compromise. This change was viewed by [[Free-Soil Party|Free Soilers]] and many abolitionist Northerners as an aggressive, expansionist maneuver by the slave-owning South, and led to the creation of the [[History of the United States Republican Party|Republican Party]]. |

||

Revision as of 19:24, 29 January 2014

MR JELLY

The Missouri Compromise was implicitly repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, submitted to Congress by Stephen A. Douglas in January 1854. The Act opened Kansas Territory and Nebraska Territory to slavery and future admission of slave states by allowing white male settlers in those territories to determine through "popular sovereignty" whether they would allow slavery within each territory. Thus, the Kansas-Nebraska Act effectively undermined the prohibition on slavery in territory north of 36°30′ latitude which had been established by the Missouri Compromise. This change was viewed by Free Soilers and many abolitionist Northerners as an aggressive, expansionist maneuver by the slave-owning South, and led to the creation of the Republican Party.

In what Republicans would label its "obiter dictum", the Supreme Court declared that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional in Dred Scott v. Sandford. Among its arguments, the Taney Court held that the Fifth Amendment barred any law that would deprive a slaveholder of his property, such as his slaves, upon the incidence of migration into free territory. This was the second time in United States history that the Supreme Court had found an act of Congress to be unconstitutional. (The first time was 54 years earlier in Marbury v. Madison). The decision would prove to be an indirect catalyst for the American Civil War.

Development in Congress

To balance the number of "slave states" and "free states," the northern region of what was then Massachusetts ultimately gained admittance into the United States as a free state to become Maine. This only occurred as a result of a compromise involving slavery in Missouri, and in the federal territories of the American west.[1] A bill to enable the people of the Missouri Territory to draft a constitution and form a government preliminary to admission into the Union came before the House of Representatives in Committee of the Whole, on February 13, 1819. James Tallmadge of New York offered an amendment, named the Tallmadge Amendment, that forbade further introduction of slaves into Missouri, and mandated that all children of slave parents born in the state after its admission should be free at the age of 25. The committee adopted the measure and incorporated it into the bill as finally passed on February 17, 1819, by the house. The United States Senate refused to concur with the amendment, and the whole measure was lost.[2][3]

During the following session (1819–1820), the House passed a similar bill with an amendment, introduced on January 26, 1820, by John W. Taylor of New York, allowing Missouri into the union as a slave state. The question had been complicated by the admission in December of Alabama, a slave state, making the number of slave and free states equal. In addition, there was a bill in passage through the House (January 3, 1820) to admit Maine as a free state.[4]

The Senate decided to connect the two measures. It passed a bill for the admission of Maine with an amendment enabling the people of Missouri to form a state constitution. Before the bill was returned to the House, a second amendment was adopted on the motion of Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois, excluding slavery from the Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30′ north (the southern boundary of Missouri), except within the limits of the proposed state of Missouri.[5]

The vote in the Senate was 24 for the compromise, to 20 against. The amendment and the bill passed in the Senate on February 17 and February 18, 1820.[5] The House then approved the Senate compromise amendment, on a vote of 90 to 87, with those 87 votes coming from free state representatives opposed to slavery in the new state of Missouri.[5] The House then approved the whole bill, 134 to 42 (the latter votes being from southern states).[5]

Second Missouri Compromise

The two houses were at odds not only on the issue of slavery, but also on the parliamentary question of the inclusion of Maine and Missouri within the same bill. The committee recommended the enactment of two laws, one for the admission of Maine, the other an enabling act for Missouri. They recommended against having restrictions on slavery but for including the Thomas amendment. Both houses agreed, and the measures were passed on March 5, 1820, and signed by President James Monroe on March 6.

The question of the final admission of Missouri came up during the session of 1820–1821. The struggle was revived over a clause in Missouri's new constitution (written in 1820) requiring the exclusion of "free negroes and mulattoes" from the state. Through the influence of Henry Clay, an act of admission was finally passed, upon the condition that the exclusionary clause of the Missouri constitution should "never be construed to authorize the passage of any law" impairing the privileges and immunities of any U.S. citizen. This deliberately ambiguous provision is sometimes known as the Second Missouri Compromise.[6]

Impact on political discourse

During the decades following 1820 Americans hailed the 1820 agreement as an essential compromise almost on the sacred level of the Constitution itself.[7] The Civil War broke out in 1861; historians often say the Compromise helped postpone the war.[8]

These disputes involved the competition between the southern and northern states for power in Congress and for control over future territories. There were also the same factions emerging as the Democratic-Republican party began to lose its coherence.

In an April 22 letter to John Holmes, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the division of the country created by the Compromise Line would eventually lead to the destruction of the Union:[9]

...but this momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. it is hushed indeed for the moment. but this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence. A geographical line, coinciding with a marked principle, moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be obliterated; and every new irritation will mark it deeper and deeper.[10][11]

Congress' consideration of Missouri's admission also raised the issue of sectional balance, for the country was equally divided between slave and free states with eleven each. To admit Missouri as a slave state would tip the balance in the Senate (made up of two senators per state) in favor of the slave states. For this reason, northern states wanted Maine admitted as a free state.

On the constitutional side, the Compromise of 1820 was important as the example of Congressional exclusion of slavery from U.S. territory acquired since the Northwest Ordinance.

Following Maine's 1820[12] and Missouri's 1821[13] admissions to the Union, no other states were admitted until 1836, when Arkansas was admitted.[14]

Repeal

The provisions of the Missouri Compromise forbidding slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30′ north were effectively repealed by the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854, despite efforts made to fight the Act by prominent speakers, including Abraham Lincoln[15] in his "Peoria Speech."

In the Dred Scott v. Sandford case in 1857, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress did not have authority to prohibit slavery in territories, and that those provisions of the Missouri Compromise were unconstitutional.[16]

See also

- Compromise of 1790

- Compromise of 1850

- Kansas–Nebraska Act

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Royal Colonial Boundary of 1665

- Tallmadge Amendment

References

- ^ Dixon, 1899 p.184

- ^ Dixon, 1899 pp.49-51

- ^ Forbes, 1899 pp.36-38

- ^ Dixon, 1899 pp.58-59

- ^ a b c d Greeley, Horace. A History of the Struggle for Slavery Extension Or Restriction in the United States, p. 28 (Dix, Edwards & Co. 1856, reprinted by Applewood Books 2001).

- ^ Dixon, 1899 pp.116-117

- ^ Paul Finkelman (2011). Millard Fillmore: The 13th President, 1850-1853. Henry Holt. p. 39.

- ^ Leslie Alexander (2010). Encyclopedia of African American History. ABC-CLIO. p. 340.

- ^ Brown, 1964 p.69

- ^ Peterson, 1960 p.189

- ^ "Thomas Jefferson to John Holmes". April 22, 1820. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- ^ "Maine Becomes a State". Library of Congress. March 15, 1820. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- ^ "Missouri Becomes a State". Library of Congress. August 10, 1821. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- ^ "Arkansas Becomes a State". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- ^ "Lincoln at Peoria". Retrieved 2012-11-18.

- ^ Dixon, 1899 Chapter XVII, p.430

Bibliography

- Dixon, Mrs. Archibald (1899). The true history of the Missouri compromise and its repeal.

The Robert Clarke company. p. 623. Url - Forbes, Robert Pierce (2007). The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery and the Meaning of America.

Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 369. ISBN 9780807831052. Url - Howe, Daniel Walker. (2010). "Missouri, Slave Or Free?" American Heritage,

- Vol. 60 Issue 2, p21-23 [online]

- Peterson, Merrill D. (1960). The Jefferson Image in the American Mind.

University of Virginia Press. p. 548. ISBN 0-8139-1851-0. Url - Wilentz, Sean. (2004).Jeffersonian Democracy and the Origins of Political Antislavery in the United States: The Missouri Crisis Revisited,

Journal of the Historical Society, Vol. 4 Issue 3, pp 375–401 - Humphrey, Rev. Heman, D.D (1854). THE MISSOURI COMPROMISE.

Reed, Hull & Peirson, Pittsfield. p. 32.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Url

- Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Further reading

- Brown, Richard Holbrook. (1964). The Missouri compromise: political statesmanship or unwise evasion?,

- Heath, pp.85, Url

- Moore, Glover. (1967). The Missouri controversy, 1819-1821,

- University of Kentucky Press (Original from Indiana University), pp.383, Url

- Woodburn, James Albert. (1894). The historical significance of the Missouri compromise,

- Government Printing Office, Washington DC, pp.297, Url