Taijitu: Difference between revisions

Rescuing orphaned refs ("Peyre 1982, 62−64" from rev 640036143; "Monastra 2000; Nickel 1991, 146, fn. 5; White & Van Deusen 1995, 12, 32; Robinet 2008, 934" from rev 640036143; "Celtic yin yang" from rev 640036143) |

Entlantian (talk | contribs) m →Gallery: fixed gallery formatting error. It broke all sections below it. |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

File:BatQuaiDo 2.svg|Bat Quai Do: Taijitu with [[I Ching]] trigrams |

File:BatQuaiDo 2.svg|Bat Quai Do: Taijitu with [[I Ching]] trigrams |

||

File:Flag of South Korea.svg|([[Taegeuk]] in Korean) in the [[flag of South Korea]] |

File:Flag of South Korea.svg|([[Taegeuk]] in Korean) in the [[flag of South Korea]] |

||

</gallery> |

|||

==In Unicode== |

==In Unicode== |

||

[[Unicode]] features the taijitu in the [[Miscellaneous Symbols]] block, at code point U+262F YIN YANG (<span style="font-size:1.8em; vertical-align:bottom;">☯</span>). The related "double body symbol" is included at U+0FCA TIBETAN SYMBOL NOR BU NYIS -KHYIL (<span style="font-size:2.2em; vertical-align:bottom;">࿊</span>), in the [[Tibetan alphabet|Tibetan]] block, among other symbols used in religious texts. |

[[Unicode]] features the taijitu in the [[Miscellaneous Symbols]] block, at code point U+262F YIN YANG (<span style="font-size:1.8em; vertical-align:bottom;">☯</span>). The related "double body symbol" is included at U+0FCA TIBETAN SYMBOL NOR BU NYIS -KHYIL (<span style="font-size:2.2em; vertical-align:bottom;">࿊</span>), in the [[Tibetan alphabet|Tibetan]] block, among other symbols used in religious texts. |

||

Revision as of 15:55, 3 February 2015

| Taijitu | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 太極圖 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太极图 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 태극도 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | たいきょくず | ||||||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 太極図 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The taijitu (Traditional Chinese: 太極圖; Simplified Chinese: 太极图; Pinyin: tàijítú; Wade-Giles: t'ai⁴chi²t'u²; rough English translation: “diagram of supreme ultimate”) is a Chinese symbol for the concept of yin and yang (Taiji). It is the universal symbol of the religion known as Taoism and is also often used by non-Taoists to represent the concept of opposites existing in harmony. The taijitu consists of a rotated pattern inside a circle. One common pattern has an S-shaped line that divides the circle into two equal parts of different colors. The pattern may have one or more large dots. The classic Daoist taijitu (pictured right), for example, is black and white with a black dot upon the white background, and a white dot upon the black background.

Patterns similar to the taijitu also form part of Celtic, Etruscan, Roman and much earlier Cucuteni-Trypillian culture iconography, sometimes descriptively dubbed "yin yang symbols" in archaeological literature by modern scholars.[1][2][3]

Geometric figure

The taijitu is a simple geometric figure, consisting of variations of nested circles. The classical Taoist symbol can be drawn with the help of a compass and straightedge: one draws on the diameter of a circle two non-overlapping circles each of which has a diameter equal to the radius of the outer circle. One keeps the line that forms an "S," and one erases or obscures the other line.[4] Thus, one obtains a form which Taoist texts liken to a pair of fishes nestling head to tail against each other.[5] This basic pattern is not a pure product of human imagination, but also occurs − of less geometrical precision − in nature (see image at the right). In the most common Daoist variant, the two differently colored halves additionally contain one dot each of opposite color.[5]

Taoist symbolism

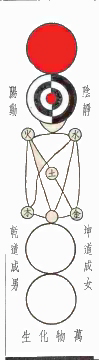

The term taijitu (literally "diagram of the supreme ultimate") is, in modern times, commonly used to mean the simple "divided circle" form (![]() ), but it may refer to any of several schematic diagrams that contain at least one circle with an inner pattern of symmetry representing yin and yang — for example, the one at right, which was Zhou Dunyi's (1017–1073) original form of the diagram.[6] It was later popularized further in China by Ming period author Lai Zhide (1525–1604).

), but it may refer to any of several schematic diagrams that contain at least one circle with an inner pattern of symmetry representing yin and yang — for example, the one at right, which was Zhou Dunyi's (1017–1073) original form of the diagram.[6] It was later popularized further in China by Ming period author Lai Zhide (1525–1604).

In the taijitu, the circle itself represents a whole (see wuji), while the black and white areas within it represent interacting parts or manifestations of the whole. The white area represents yang elements, and is generally depicted as rising on the left, while the dark (yin) area is shown descending on the right (though other arrangements exist, most notably the version used on the flag of South Korea). The image is designed to give the appearance of movement. Each area also contains a large dot of a differing color at its fullest point (near the zenith and nadir of the figure) to indicate how each will transform into the other.

The Taijitu symbol is an important symbol in martial arts, particularly t'ai chi ch'uan (Taijiquan),[7] and Jeet Kune Do. In this context, it is generally used to represent the interplay between hard and soft techniques.

Taijitu shuo

The Song Dynasty philosopher Zhou Dunyi (1017–1073) wrote the Taijitu shuo 太極圖說 "Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate", which became the cornerstone of Neo-Confucianist cosmology. His brief text synthesized aspects of Chinese Buddhism and Taoism with metaphysical discussions in the Yijing.

Zhou's key terms Wuji and Taiji appear in the opening line 無極而太極, which Adler notes could also be translated "The Supreme Polarity that is Non-Polar".

Non-polar (wuji) and yet Supreme Polarity (taiji)! The Supreme Polarity in activity generates yang; yet at the limit of activity it is still. In stillness it generates yin; yet at the limit of stillness it is also active. Activity and stillness alternate; each is the basis of the other. In distinguishing yin and yang, the Two Modes are thereby established. The alternation and combination of yang and yin generate water, fire, wood, metal, and earth. With these five [phases of] qi harmoniously arranged, the Four Seasons proceed through them. The Five Phases are simply yin and yang; yin and yang are simply the Supreme Polarity; the Supreme Polarity is fundamentally Non-polar. [Yet] in the generation of the Five Phases, each one has its nature.[8]

Instead of usual Taiji translations "Supreme Ultimate" or "Supreme Pole", Adler uses "Supreme Polarity" (see Robinet 1990) because Zhu Xi describes it as the alternating principle of yin and yang, and ...

insists that taiji is not a thing (hence "Supreme Pole" will not do). Thus, for both Zhou and Zhu, taiji is the yin-yang principle of bipolarity, which is the most fundamental ordering principle, the cosmic "first principle." Wuji as "non-polar" follows from this.

Gallery

-

Ancient form of the Taijitu, as used by Lai Zhide

-

Bat Quai Do: Taijitu with I Ching trigrams

-

(Taegeuk in Korean) in the flag of South Korea

In Unicode

Unicode features the taijitu in the Miscellaneous Symbols block, at code point U+262F YIN YANG (☯). The related "double body symbol" is included at U+0FCA TIBETAN SYMBOL NOR BU NYIS -KHYIL (࿊), in the Tibetan block, among other symbols used in religious texts.

See also

Similar symbols:

References

- ^ Peyre 1982, pp. 62−64, 82 (pl. VI); Harding 2007, pp. 68f., 70f., 76, 79, 84, 121, 155, 232, 239, 241f., 248, 253, 259; Duval 1978, p. 282; Kilbride-Jones 1980, pp. 127 (fig. 34.1), 128; Laing 1979, p. 79; Verger 1996, p. 664; Laing 1997, p. 8; Mountain 1997, p. 1282; Leeds 2002, p. 38; Morris 2003, p. 69; Megaw 2005, p. 13

- ^ Peyre 1982, pp. 62−64

- ^ Monastra 2000; Nickel 1991, p. 146, fn. 5; White & Van Deusen 1995, pp. 12, 32; Robinet 2008, p. 934

- ^ Peyre 1982, pp. 62f.

- ^ a b Robinet 2008, p. 934

- ^ Xinzhong Yao (13 February 2000). An introduction to Confucianism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-0-521-64430-3. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ Davis, Barbara (2004). Taijiquan Classics. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-55643-431-0.

- ^ Adler, Joseph A. (1999). "Zhou Dunyi: The Metaphysics and Practice of Sagehood", in Sources of Chinese Tradition, William Theodore De Bary and Irene Bloom, eds. 2nd ed., 2 vols. Columbia University Press. pp. 673-674.

Sources

Taoist symbolism

- Robinet, Isabelle (2008), "Taiji tu. Diagram of the Great Ultimate", in Pregadio, Fabrizio (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Taoism A−Z, Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 934−936, ISBN 978-0-7007-1200-7

European iconography

- Altheim, Franz (1951), Attila und die Hunnen, Baden-Baden: Verlag für Kunst und Wissenschaft

- Benoist, Alain de (1998), Communisme et nazisme: 25 réflexions sur le totalitarisme au XXe siècle, 1917-1989, ISBN 2-86980-028-2

- Duval, Paul-Marie (1978), Die Kelten, München: C. H. Beck, ISBN 3-406-03025-4

- Fink, Josef; Ahrens, Dieter (1984), "Thiasos ton mouson. Studien zu Antike und Christentum", Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, 20, ISBN 3-412-05083-0

- Harding, D. W. (2007), The Archaeology of Celtic Art, Routledge, ISBN 0-203-69853-3

- Kilbride-Jones, H. E. (1980), Celtic Craftsmanship in Bronze, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-7099-0387-1

- Laing, Lloyd (1979), Celtic Britain, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 0-7100-0131-2

- Laing, Lloyd (1997), Later Celtic Art in Britain and Ireland, Shire Publications LTD, ISBN 0-85263-874-4

- Leeds, E. Thurlow (2002), Celtic Ornament in the British Isles, E. T. Leeds, ISBN 0-486-42085-X

- Megaw, Ruth and Vicent (2005), Early Celtic Art in Britain and Ireland, Shire Publications LTD, ISBN 0-7478-0613-6

- Monastra, Giovanni (2000), "The "Yin-Yang" among the Insignia of the Roman Empire?", Sophia, 6 (2)

- Morris, John Meirion (2003), The Celtic Vision, Ylolfa, ISBN 0-86243-635-4

- Mountain, Harry (1997), The Celtic Encyclopedia, vol. 5, ISBN 1-58112-894-0

- Nickel, Helmut (1991), "The Dragon and the Pearl", Metropolitan Museum Journal, 26: 139–146, doi:10.2307/1512907

- Peyre, Christian (1982), "Y a-t'il un contexte italique au style de Waldalgesheim?", in Duval, Paul-Marie; Kruta, Venceslas (eds.), L’art celtique de la période d’expansion, IVe et IIIe siècles avant notre ère, Hautes études du monde gréco-romain, vol. 13, Paris: Librairie Droz, pp. 51–82 (62–64, 82), ISBN 978-2-600-03342-8

- Sacco, Leonardo (2003), "Aspetti 'storico-religiosi' del Taoismo (parte seconda)", Studi e materiali di storia delle religioni, vol. 27, no. 1–2, Università di Roma, Scuola di studi storico-religiosi

- Verger, Stéphane (1996), "Une tombe à char oubliée dans l'ancienne collection Poinchy de Richebourg", Mélanges de l'école française de Rome, vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 641–691

- White, Lynn; Van Deusen, Nancy Elizabeth (1995), The Medieval West Meets the Rest of the World, Claremont Cultural Studies, vol. 62, Institute of Mediaeval Music, ISBN 0-931902-94-0

External links

![]() Media related to Yin Yang at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yin Yang at Wikimedia Commons