Korean influence on Japanese culture: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 662643792 by CurtisNaito (talk)That is incorrect. Like I said (and Nishidani has already said as well), please take each respective edit up individually. |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''Korean influence on Japanese culture''' refers to the impact of Korea on [[Culture of Japan|Japanese institutions and society]]. Such influence has existed since prehistoric times in the form of the transfer of Korean immigrants, technology, ideas, art, and artistic techniques to Japan. Many such innovations had originated in China, but were adapted and modified in Korea before reaching Japan. |

|||

{{Original research|date=May 2015}} |

|||

{{POV|date=May 2015}} |

|||

<!-- Do not remove these tags again until the issues with this article have been resolved. The first (enormous, highly dubious) section ("Art") remains largely unchanged since the AFD. ~Hijiri88, May 2015. --> |

|||

The '''Korean influence on Japanese culture''' refers to the impact of [[Culture of Korea|continental influences transmitted through or originating in]] the [[Korean Peninsula]] on [[Culture of Japan|Japanese institutions, culture, language and society]]. Since the Korean Peninsula was the cultural bridge between [[Japan]] and the Asian continent throughout much of Far Eastern history, these influences, whether hypothesized or ascertained, have been detected in a notable variety of aspects of Japanese culture. Korea played a significant role in in the introduction of [[Buddhism]] to Japan from [[India]] via the Kingdom of [[Baekje]]. The modulation of continental styles of art in Korea has also been discerned in early [[Japanese painting]] and [[Japanese architecture|architecture]], ranging from the [[Buddhist temples in Japan|design of Buddhist temples]] to various smaller objects such as [[statues]], [[textiles]] and [[ceramic art|ceramics]].{{citation needed|date=October 2014}} The role of ancient Korean states in the transmission of continental civilization, often moulded in turn by peninsular innovations, has long been neglected, and is increasingly the object of academic study. <ref>Paul Varley, [https://books.google.it/books?id=BvUEzBin61AC&pg=PA25 ''Japanese Culture,'' University of Hawaii Press, 2000 p.26.</ref> Korean and Japanese nationalisms have, in different ways, complicated the interpretation of these influences.<ref>Keith Pratt, Richard Rutt,[https://books.google.it/books?id=r15cAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA235 ''Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary,''] Routledge (1999) 2013 p.235.</ref><ref> Kelly Boyd (ed.),[https://books.google.it/books?id=JBqWbDmFsfEC&pg=PA659 ''Encyclopedia of Historians and Historical Writing,''] Taylor & Francis, 1999 vol.1, p.569ff.</ref> |

|||

Notable examples of Korean influence on Japanese culture include the prehistoric migration of Korean peoples to Japan which helped spark Japan's transition from a [[Jomon Period|stone age]] to an [[Yayoi Period|iron age]] society, the introduction of Buddhism to Japan from the Korean state of [[Baekje]] in 538 AD, and the rebirth of Japanese pottery in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by Koreans craftsmen forced to go to Japan during the [[Japanese invasions of Korea]]. Throughout history Korea has influenced state formation in Japan in a significant manner and also exerted long-term influence on Japanese art, including painting and architecture. |

|||

== Art == |

|||

During the [[Asuka Period]], the artisans from [[Baekje]] provided technological and [[aesthetic]] guidance in the Japanese architecture and arts.<ref name="Kodansha encyclopedia of Japan">Kodansha encyclopedia of Japan. [[Kodansha]], 1983, p. 146</ref> Therefore, the temple plans, architectural forms, and iconography were strongly influenced directly by examples in the ancient Korea.<ref>Donald F. McCallum. The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan. University of Hawai'i Press, 2009</ref>{{Page needed|date=October 2014}}<ref>Neeraj Gautam. Buddha his life and teaching. Mahaveer & Sons, 2009</ref>{{Page needed|date=October 2014}} In deed, many of the Japanese temples at that time were crafted in the Baekje style.<ref>Donald William Mitchell. Buddhism: introducing the Buddhist experience. Oxford University Press, 2008, p.276</ref> Japanese nobility, wishing to take advantage of culture from across the sea, {{Citation needed span|text=imported artists and artisans from the Korean Peninsula (most, but not all, from Baekje) to build and decorate their first palaces and temples.|date=June 2011}} |

|||

Until recently, Korean influence on Japanese culture was a relatively neglected topic among scholars, who instead focused on China's influence on Japan. By contrast, many scholars today acknowledge the key role played by Korea in bringing advanced culture to Japan. According to the Kyoto Cultural Museum, "In seeking the source of Japan’s ancient culture many will look to China, but the quest will finally lead to Korea, where China’s advanced culture was accepted and assimilated. In actuality, the people who crossed the sea were the people of the Korea Peninsula and their culture was the Korean culture."<ref name="rhee">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 405.</ref> |

|||

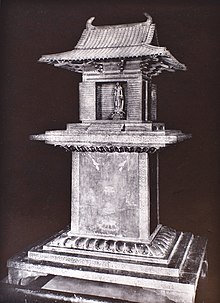

Among the earliest craft items extant in Japan is the [[Tamamushi shrine]], a magnificent example of [[Korean art]] of that period.<ref>The Theosophical Path: Illustrated Monthly, C.J. Ryan. Art in China and Japan. New Century Corp.,July 1914, p. 10</ref><ref name="Fenollosa">{{cite book |author=[[Ernest Fenollosa|Fenollosa, Ernest F]] |title=Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art: An Outline History of East Asiatic Design |publisher=[[Heinemann (publisher)|Heinemann]] |year=1912 | page=49}}</ref> The shrine is a miniature two-story temple made of wood, to be used as a kind of reliquary.<ref name="Fenollosa"/> This shrine is so named because it was decorated with iridescent beetle([[Tamamushi]]) wings set into metal edging, a technique also Korean indigenous<ref name="Mizuno1974">Mizuno, Seiichi. Asuka Buddhist Art: Hōryū-ji. Weatherhill, 1974. New York, p.40</ref><ref>Stanley-Baker, Joan. Japanese Art. [[Thames & Hudson]], 1984, p. 32</ref> practiced in Korea<ref>Conrad Schirokauer,Miranda Brown,David Lurie,Suzanne Gay. A Brief History of Chinese and Japanese Civilizations. Wadworth engage Learning, 2003, p.40</ref><ref>Paine, Robert Treat; Soper, Alexander Coburn. The Art and Architecture of Japan. Yale University Press, 1981. pp. 33-35, 316.</ref> and this technique of tamamushi inlay is evidently native to Korea.<ref>Beatrix von Ragué. A history of Japanese lacquerwork. University of Toronto Press, 1976, p.6</ref> The shrine's ornamental gilt bronze openwork, inlaid with the iridescent wings of the tamamushi beetle, is of a Korean type.<ref>Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), James C. Y. Watt, Barbara Brennan Ford. East Asian lacquer: the Florence and Herbert Irving collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1991, p.154</ref> |

|||

== Prehistoric contacts and the Jomon-Yayoi transition == |

|||

=== Architecture === |

|||

During the stone age Jomon Period of Japanese history, the people living in Japan imported some items from Korea but otherwise remained in isolation from continental Asia.<ref name="diamond">Jared Diamond, "In Search of Japanese Roots," ''Discover'', June 1998, 91-92.</ref> However, starting from around 400 BC Korean technology and cultural objects suddenly began appearing in Japan.<ref name="diamond"/><ref name="yayoi">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 416-422.</ref> During this new period of Japanese history, the Yayoi Period, the forms of intensive agriculture and animal husbandry practiced in Korea were adopted in Japan, first in Kyushu which is closest to the Korean peninsula and soon all across Japan.<ref name="diamond"/><ref name="yayoi"/> The result was a major explosion in the Japanese population from 75,000 people in 400 BC to over five million by 250 AD.<ref name="diamond"/><ref name="yayoi"/> Japanese people also began to use metal tools, arrowheads, new forms of pottery, glass beads, weaving, moats, burial mounds, and styles of housing which were of Korean origin.<ref name="diamond"/><ref name="yayoi"/> |

|||

The oldest Japanese Buddhist temple, [[Asuka-dera]], constructed under the guidance of craftsmen from the ancient Korean kingdom of Baekje, from 588-596.<ref>Donald Fredrick McCallum, [https://books.google.it/books?id=OAyk-ObsD6sC&pg=PA40 ''The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan,''] University of Hawaii Press, 2009 pp.40-46.</ref><ref>Kakichi Suzuki,''Early Buddhist architecture in Japan,'' Kodansha International, 1980, p.43</ref> was modeled upon the layout and architecture of Baekje.<ref>Herbert E. Plutschow. Historical Nara: with illustrations and guide maps. Japan Times, 1983, p. 41</ref> And one of the early great temples in Japan, such as the [[Shitennō-ji]] Temple was based on types from the ancient Korea.<ref>Asoke Kumar Bhattacharyya. Indian contribution to the development of Far Eastern Buddhist iconography. K.P. Bagchi & Co., 2002, p. 22</ref><ref name="LouisFrédéric2002">Louis Frédéric. Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press, 2002, p.136</ref> |

|||

In 601, [[Prince Shōtoku]] began the construction of his palace, the first building in Japan to have a tiled roof. Next to it he built his temple, which became known as [[Hōryū-ji]]. He employed a number of skilled craftsmen, monks, and designers from [[Baekje]] for this project.<ref>Mizuno, Seiichi. Asuka Buddhist Art: Hōryū-ji. Weatherhill, 1974. New York, p.14</ref><ref>Nishi and Hozumi Kazuo. What is Japanese Architecture? Shokokusha Publishing Company, 1983. Tokyo</ref>{{Page needed|date=October 2014}} The temple became his personal devotional center where he studied with Buddhist priests [[Hyeja]] and [[Damjing]] from the Korean kingdom of [[Goguryeo]]; it also housed people who practiced medicine, medical knowledge being another by-product of Buddhism. Next to the temple there were dormitories which housed student-monks and teacher-monks.<ref name="az">[http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/shotoku-taishi.html] Mark Schumacher. A to Z Photo Dictionary of Japanese Buddhist Statuary.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Yoshinogari1.jpg|thumb|right|The archeology of the Yoshinogari site is virtually identical to a Korean village]]There has never been any doubt that technology and culture from Korea played a critical role in Japan's transition from the Jomon Period to the Yayoi Period, but historians continue to debate whether the transition occurred primarily due to adaptation of Korean technology and culture by indigenous Japanese people or primarily due to immigration of new people from Korea.<ref name="influence">Jared Diamond, "In Search of Japanese Roots," ''Discover'', June 1998, 93.</ref> According to the anthropologist [[Jared Diamond]], genetic studies and anatomical evidence from early Japanese people prove that "immigrants from Korea really did make a big contribution to the modern Japanese" and that "By the time of the [[Kofun Period]], all Japanese skeletons except those of the [[Ainu]] form a homogeneous group, resembling modern Japanese and Koreans."<ref name="influence"/> New advances in agriculture and rapid population growth within Korea are believed to have been the major causes of this sudden influx of Korean immigration to Japan.<ref name="diamond"/><ref name="rhee"/> The total number who migrated to Japan at this time is unknown but may have been up to several million, most of whom were men who married women native to Japan.<ref name="influence"/><ref name="yayoi"/> The [[Yoshinogari site]], a famous archeological site in [[Kyushu]] dating from the late Yayoi Period, appears virtually identical to Korean villages of the same period.<ref name="bronze">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 430-432.</ref> Diamond also suspects that the new migrants spoke a Japanese language which was derived from a language of the Korean peninsula,<ref name="language">Jared Diamond, "In Search of Japanese Roots," ''Discover'', June 1998, 86, 95.</ref> a theory which is also advocated by [[Christopher Beckwith]].<ref>Christopher Beckwith, "The Ethnolinguistic History of the Early Korean Peninsula Region," ''Journal of Inner and East Asian Studies'', December 2005, 34.</ref> |

|||

The first Horyu-ji burned to the ground in 670. It was rebuilt, and although it is thought to be smaller than the original temple, Horyu-ji today is much the same in design as the one originally built by Shotoku. Again, the temple was rebuilt by artists and artisans from Baekje.<ref name="az"/> The bracket work of a Baekje gilt bronze pagoda matches the Hōryū-ji bracket work exactly.<ref>Shin, Young-hoon. "Audio/Slide Program for Use in Korean Studies, ARCHITECTURE". Indiana University.</ref> The wooden pagoda at Horyu-ji, as well as the Golden Hall, are thought to be masterpieces of seventh-century Baekje architecture.<ref name="az"/> Two other temples, [[Hokki-ji]] and [[Hōrin-ji (Nara)|Horin-ji]], were also probably built by artisans of Korea’s Baekje kingdom.<ref>[http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/asuka-art.html] Mark Schumacher. A to Z Photo Dictionary of Japanese Buddhist Statuary.</ref> |

|||

Throughout the remainder of the Yayoi Period Japan relied heavily on Korea as a source of tools and weapons made of bronze and iron.<ref name="bronze"/> During this period Japan imported great numbers of Korean mirrors and daggers, which were the symbols of power in Korea.<ref name="bronze"/> Combined with the curved jewel known as the [[magatama]], Korea's "three treasures" soon became as prized by Japan's elites as Korea's, and in Japan they would later become the [[Imperial Regalia of Japan|Imperial Regalia]].<ref name="bronze"/> |

|||

=== Sculptures === |

|||

[[File:Kudara kannon 1.JPG|thumb|160px|right|Kudara kannon]] |

|||

One of the most famous of all Buddhist sculptures from the Asuka period found in Japan today is the "[[Horyu-ji#Kudara Kannon|Kudara Kannon]]" which, when translated, means "[[Baekje]] [[Guanyin]]."(Kudara is the Japanese name for the Korean kingdom of Baekje<ref>Peter C. Swann. A concise history of Japanese art. Kodansha International, 1979, p. 44</ref>) This wooden statue was either brought from Korean Baekje or carved by a Korean immigrant sculptor from Baekje.<ref>Peter C. Swann. The art of Japan, from the Jōmon to the Tokugawa period. Crown Publishers, 1966, p.238</ref><ref>Ananda W. P. Gurugé. Buddhism, the religion and its culture. M. Seshachalam, 1975</ref>{{Page needed|date=October 2014}}<ref>Jane Portal. Korea: art and archaeology. British Museum, 2000, p. 240</ref> It formerly stood as the central figure in the Golden Hall at the Horyu-ji. {{Citation needed span|text=It was moved to a glass case in the Treasure Museum after a fire destroyed part of the Golden Hall in 1949.|date=April 2010}} "This tall, slender, graceful figure made from camphor wood is reflective of the most genteel state in the Three Kingdoms period. From the openwork crown to the lotus pedestal design, the statue marks the superior workmanship of 7th century [[Baekje|Paekche]] artists."{{citation needed|date=October 2014}} The first and foremost clue that clearly indicates Baekje handiwork is the crown's design, which shows the characteristic honeysuckle-lotus pattern found in artifacts buried in the tomb of King Munyong of Baekje (reigned 501-523).{{cn|date=October 2014}} The number of protrusions from the petals is identical, and the coiling of the vines appears to be the same. Crowns of a nearly identical type remain in Korea, executed in both gilt bronze and granite. The crown's pendants indicate a carryover from [[Korean shamanism|shamanist]] designs seen in fifth-century Korean crowns.{{Citation needed span|text=Guanyin's bronze bracelets and those of the [[Four Heavenly Kings]] at the Golden Hall also show signs of similar openwork metal techniques.|date=April 2010}} |

|||

== Korean influence on ancient and classical Japan == |

|||

[[File:GUZE Kannon Horyuji.JPG|thumb|160px|left|Guze Kannon]] |

|||

During the Kofun Period of ancient Japanese history, which begins around 250 AD, the tribes of Japan gradually coalesced into a centralized state.<ref name="history">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 432, 437-439, 447.</ref> Cultural contact with Korea, which at the time was divided into several independent states, played a decisive role in the development of Japanese government and society both during the Kofun Period and the subsequent [[Classical Japan|Classical Period]].<ref name="farris">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 69-70, 110, 116, 120-122.</ref><ref name="history"/> Most new innovations flowed from Korea into Japan, and not vice-versa, primarily due to Korea's closer proximity to China.<ref>Ch'on Kwan-u, "A New Interpretation of the Problems of Mimana (I)," ''Korea Journal'', February 1974, 11.</ref> Though many of the ideas and technologies which filtered into Japan from Korea were originally Chinese, historian William Wayne Farris notes that native Koreans put "their distinctive stamp on" them before passing them on to Japan.<ref name="farris"/> Some such innovations were imported to Japan through trade, but in more cases they were brought to Japan by Korean immigrants.<ref name="farris"/> The [[Yamato Period|Yamato]] state that eventually unified Japan was able to accomplish this feat partly due to its success at gaining a monopoly on the importation of Korean culture and technology into Japan.<ref name="farris"/> Extensive details on these cultural contacts between Japan and Korea are provided by the earliest written histories of Japan, including the [[Nihon Shoki]] written in 720.<ref>Jared Diamond, "In Search of Japanese Roots," ''Discover'', June 1998, 89.</ref> According to Farris, Japanese cultural borrowing from Korea "hit peaks in the mid-fifth, mid-sixth, and late seventh centuries" and "helped to define a material culture that lasted as long as a thousand years."<ref>William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 68, 120.</ref> |

|||

The another Hōryū-ji statue, "[[Horyu-ji#Yumedono (Guze) Kannon|Guze Kannon]]" is made of gilded wood in the Korean style.<ref>Evelyn McCune. The arts of Korea: an illustrated history. C. E. Tuttle Co., 1962, p.69</ref> The Kannon retains most of its gilt. It is in superb condition because it was kept in the Dream Hall(Yumedono) and wrapped in five hundred meters of cloth and never viewed in sunlight. The statue which had originally come from [[Baekje]]<ref>Asiatic Society of Japan. Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. The Society, 1986, p. 155</ref> and was held to be sacred and had remained unseen until it was unwrapped at the demand of [[Ernest Fenollosa]], who was charged by the Japanese government to catalogue the art of the state and later became a curator at the Boston Museum.<ref>June Kinoshita. "Gateway to Japan", pp. 587-588. Kodansha International, 1998</ref> Fenellosa also considered the Kannon to be Korean, who described the Kudara Kannon as "the supreme masterpiece of [[Korea|Corean]] creation".<ref name="Fenollosa"/><ref>Fenollosa, Ernest F. Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art: An Outline History of East Asiatic Design. Heinemann, 1912, p.49</ref> According to the record Shogeishō (聖冏抄), a compilation of the ancient historical records and traditions about the Japanese Prince Regent [[Shotoku Taishi]], which was written by a Japanese monk [[:jp:聖冏|Shogei]] (1341-1420), the 7th Patriarchs of the [[Jōdo shū|Jodo sect]], Guze Kannon is a statue that is the representation of King [[Seong of Baekje]], which was carved under the order of the subsequent [[King Wideok of Baekje]].<ref>聖冏抄 ... 故威德王恋慕父王状所造顕之尊像 即救世観音像是也</ref> |

|||

=== Korean immigration to Japan === |

|||

More examples of Korea's influence were noted in the [[New York Times]], whose reporter writes when looking at Japan's national treasures like the "[[Kōryū-ji#Wooden statue of Bodhisattva|Hokan Miroku]]" sculpture which came from [[Silla]]<ref>Mizuno, Seiichi. Asuka Buddhist Art: Hōryū-ji. Weatherhill, 1974. New York, p. 80</ref><ref>Asia, Volume 2. [[Asia Society]], 1979</ref> and has been preserved at [[Kōryū-ji]] Temple ; "''It is also a symbol of Japan itself and an embodiment of qualities often used to define Japaneseness in art: formal simplicity and emotional serenity. To see it was to have an instant Japanese experience. I had mine. As it turns out, though, the Koryuji sculpture isn't Japanese at all. Based on Korean prototypes, it was almost certainly carved in Korea''"<ref name="NYT 2003">[[#NYTArts|NYT (2003): Japanese Art]]</ref> and ''"The obvious upshot of the show's detective work is to establish that certain classic "Japanese" pieces are actually "Korean".''<ref name="NYT 2003"/> |

|||

[[File:Three_Kingdoms_of_Korea_Map.png|thumb|right|Throughout much of ancient Japanese history Korea was divided into several warring kingdoms]]During this period the major factor behind the transfer of Korean culture to Japan was immigration from Korea.<ref name="koreans">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 405, 433-436.</ref> Most Korean immigrants, generically known as toraijin in Japanese, came during a period of intense regional warfare which racked the Korean peninsula between the years 371 and 670.<ref name="koreans"/> Most of these immigrants were from Japan's allies, the Korean states of Baekje and [[Gaya confederacy|Gaya]], and they were warmly welcomed by the Japanese government.<ref name="koreans"/> Perhaps most significant of all was the flight of the Baekje elite, who came to Japan in two waves in 400 and 475 during invasions of Baekje by the Korean kingdom of [[Goguryeo]] and then again in 663 after Baekje fell to the kingdom of [[Silla]].<ref>Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 438, 444.</ref> These immigrants brought their culture to Japan with them, and once there they often became leading officials, soldiers, artists, and craftsmen.<ref name="koreans"/> Korean immigrants were the leading players behind Japan's [[Japanese missions to Sui China|cultural missions]] to [[Sui China]]<ref name="clans">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 441-442.</ref> and some Koreans even married into the [[Imperial House of Japan|Imperial Family]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/04/080428-ancient-tomb.html|title=Japanese Royal Tomb Opened to Scholars for First Time|author=Tony McNicol|publisher=''National Geographic News''|date=April 28, 2008}}</ref><ref name="kim">Jinwung Kim, ''A History of Korea: From 'Land of the Morning Calm' to States in Conflict'' (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 75.</ref> |

|||

By 700 perhaps one third of all Japanese aristocrats were of recent Korean origin,<ref name="farris"/> including the influential Aya clan and [[Hata clan]].<ref name="clans"/> Although Koreans settled throughout Japan, they were especially concentrated in [[Nara Prefecture|Nara]], the region where the Japanese capital was located.<ref name="clans"/> Between eighty and ninety percent of people living in Nara had Korean Baekje ancestry by the year 773, and recent anatomical analyses indicate that modern-day Japanese people living in this area continue to be more closely related to ethnic Koreans than any other in Japan.<ref name="clans"/> |

|||

In the 8th century, groups of Sculptors of Baekje and [[Silla]] origins participated in the construction works of [[Tōdai-ji]] Temple.<ref>Jirô Sugiyama, Samuel Crowell Morse. Classic Buddhist sculpture: the Tempyô period. Kodansha International, 1982, p.164</ref> The bronze statue of [[Daibutsu|Great Buddha]] at Tōdai-ji Temple was predominantly made by [[Koreans]].<ref name="The Association">College Art Association of America. Conference. Abstracts of papers delivered in art history sessions: Annual meeting. The Association, 1998, p.194</ref> The Great Buddha project was supervised by a Korean Baekje craftsman, Gongmaryeo (or Kimimaro in Japanese) and had many Silla craftsmen from Korea working from the beginning of the project.<ref name="The Association"/> The Great Buddha was finally cast, despite great difficulty by virtue of the skill of imported craftsmen from Silla in 752.<ref>Richard D. McBride. Domesticating the Dharma: Buddhist Cults and the Hwaŏm Synthesis in Silla Korea. University of Hawaii Press, 2008, p.90</ref> Furthermore, Silla sculpture seems to have exerted considerable influence on the styles of the early [[Heian period]] in Japan.<ref>Jirô Sugiyama, Samuel Crowell Morse. Classic Buddhist sculpture: the Tempyô period. Kodansha International, 1982, p.208</ref> |

|||

The Soga clan, a clan with close ties to the Baekje elite, may also have been of Korean Baekje ancestry.<ref name="soga">Donald McCallum, ''The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009), 19.</ref> Scholars who have argued in favor of the theory that the Soga had Korean ancestry include Song-Nai Rhee, C. Melvin Aikens, Sung-Rak Choi, Hyuk-Jin Ro, Teiji Kadowaki, and William Wayne Farris.<ref name="culture"/><ref name="soga"/><ref>William Wayne Farris, ''Japan to 1600: A Social and Economic History'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009), 25.</ref> |

|||

=== Painting === |

|||

=== Arms and armament === |

|||

In 588, the Korean painter Baekga (白加) was invited to Japan from Baekje, and in 610 the Korean priest Damjing came to Japan from [[Goguryeo]] and taught the Japanese the technique of preparing [[pigments]] and painting materials.<ref>Bernard Samuel Myers. Encyclopedia of world art. Buddhism in Japan McGraw-Hill, 1959</ref>{{Page needed|date=October 2014}}<ref>Terukazu Akiyama. Japanese painting. Skira, 1977, p. 26</ref> |

|||

During most of the Kofun Period Japan relied on Korea as its sole source of iron swords, spears, armor, and helmets.<ref name="armor">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 72-76.</ref> [[Cuirasses]] and later Japan's first [[lamellar armor]], as well as subsequent innovations in producing them, arrived in Japan from Korea, particularly the Korean states of Silla and Gaya.<ref name="armor"/><ref>Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 438.</ref> Japan's first crossbow was delivered by Goguryeo in 618.<ref name="war">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 105, 109.</ref> |

|||

At a time in history when horses were a key military weapon, Baekje immigrants also established Japan's first horse-raising farms in what would become Japan's [[Kawachi Province]].<ref name="baekje">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 438-439.</ref> One historian, Koichi Mori, theorizes that [[Emperor Keitai]]'s close friendships with Baekje horsemen played an important role in helping him to assume the throne.<ref name="baekje"/> On top of the horses themselves, Korea also gave Japan its first horse carriages and other related trappings.<ref name="horse">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 77-79.</ref><ref name="baekje"/> Bites, stirrups, saddles, and bridles entered Japan from Korea by the early fifth century.<ref name="horse"/> |

|||

In the 15th century, facing slavery and persecution as [[neo-Confucianism]] took a stronger hold during the [[Joseon Dynasty]] in Korea, many Buddhist-sympathetic artists began migrating to Japan. Once in Japan, they continued to use their Buddhist names instead of their birth (given) names, which eventually led to their origins being largely forgotten. These artists eventually married native women and raised children who were oblivious to their historical origins.{{citation needed|date=October 2014}} Many famous artists in Japan fall into this category. Yi Su-mun, who left for Japan in 1424 to escape persecution of Buddhists, painted the famous "Catching a Catfish with a Gourd". The famous [[Tenshō Shūbun]] of [[Shokoku-ji]] also arrived on the same vessel as Yi Su-mun.<ref name="InkPainting">Takaaki Matsushita. Ink Painting. Weatherhill, 1974, p. 64</ref> The Korean painter Yi Su-mun, who as artist in residence to the Asakura daimyo family of Echizen in central Japan, was to play an important role in the development of Japanese [[ink painting]]:<ref name="InkPainting"/> He is reputed to have been the founder of the painting lineage of [[Daitoku-ji]], which reached its apex at the time of the great Zen master [[Ikkyū]] and his followers.<ref>Art of Japan: paintings, prints and screens : selected articles from Orientations, 1984-2002. Orientations Magazine, 2002, p.86</ref><ref>Akiyoshi Watanabe, Hiroshi Kanazawa. Of water and ink: Muromachi-period paintings from Japan, 1392-1568, p.89</ref> |

|||

In 660 following the fall of Baekje, a Korean ally of Japan, the Japanese [[Emperor Tenji]] utilized skilled technicians from Baekje to construct at least seven fortresses to protect Japan's coastline from invasion.<ref>Michael Comoe, ''Shotoku: Ethnicity, Ritual, and Violence in the Japanese Buddhist Tradition'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 26.</ref> Japan's mountain fortifications in particular were based off Korean models.<ref name="war"/><ref>Bruce Batten, ''Gateway to Japan: Hakata in War And Peace, 500-1300'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006), 27-28.</ref> |

|||

The Soga (曽我派), a group of Japanese painters active from the 15c through the 18c, also claimed lineage from the Korean immigrant painter Yi Su-mun, and certain stylistic elements seen within the paintings of the school suggest Korean influence.<ref>Thomas Lawton, Thomas W. Lentz. Beyond the Legacy: Anniversary Acquisitions for the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. University of Washington Pr, 1999, p.312</ref> Muncheong (or Bunsei in Japanese) was another Korean immigrant painter in the 15th century Japan, known only by the seal placed on his works extant in both Japan and Korea.<ref>Yang-mo Chŏng, Judith G. Smith, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) Arts of Korea. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998</ref>{{Page needed|date=October 2014}}{{Relevance-inline|date=February 2015}}<!-- Louis Frederic was an unreliable source of information in controversial areas like this, and even if he was -- how is this relevant? If this artist is only known by his seal on some works, then how can he be considered an "influence" on later Japanese culture? --> |

|||

== |

=== Pottery === |

||

Japan continued to import new forms of pottery from Korea just as it had during the earlier Yayoi Period,<ref name="gaya">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 433, 437-438, 441.</ref> and around the early fifth century the [[tunnel kiln]] and [[potter's wheel]] also made their way from Korea to Japan.<ref name="stone">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 84-87.</ref> |

|||

Various metal-working techniques such as iron-working, the [[cuirass]], the [[oven]], bronze bells used in [[Yayoi period]] Japan essentially originated in Korea.<ref>Farris, William Wayne. Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 1998, p. 69</ref> During the [[Kofun period]], in the fifth century, large groups of craftspeople, who became the specialist gold workers, [[saddle]]rs, [[weaver (occupation)|weaver]]s, and others arrived in [[Yamato period|Yamato]] Japan from the Baekje kingdom of Korea.<ref>Brian M. Fagan. The Oxford companion to archaeology. Oxford University Press, 1996, p.362</ref><ref>Japan. Bunkachō, Japan Society (New York, N.Y.), IBM Gallery of Science and Art. The Rise of a great tradition: Japanese archaeological ceramics of the Jōmon through Heian periods (10,500 BC-AD 1185). Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan, 1990, p.56</ref> |

|||

[[File:Sueki-MorigaswaIseki.jpg|thumb|left|Sue ware]]The most notable form of pottery to reach Japan from Korea was the high-fired stoneware known as dojil togi in Korea and [[Sue ware]] in Japan which was brought by immigrants from the Korean state of Gaya.<ref name="gaya"/> Gayan refugees fleeing an attack by Goguryeo in 400 brought the first Sue ware to Japan and soon they were producing it domestically.<ref name="gaya"/> Every aristocratic tomb in Japan from that point and on would contain a profusion of Gayan sue ware, and by the 700s Japanese commoners were using it as well.<ref name="gaya"/> Baekje immigrants were also involved in creating sue ware.<ref name="gaya"/> |

|||

=== Iron ware === |

|||

Iron processing and sword making techniques in ancient Japan can be traced back to Korea. |

|||

"Early, as well as current Japanese official history cover up much of this evidence. For example, there is an iron sword in the Shrine of the Puyo Rock Deity in Asuka, Japan which is the third most important historical Shinto shrine. This sword which is inaccessible to the public has a Korean Shamanstic shape and is inscribed with Chinese characters of gold, which include a date corresponding to 369 A.D. At the time, only the most educated elite in the [[Baekje|Paekche]] Kingdom knew this style of Chinese writing".{{cn|date=October 2014}} |

|||

=== Ovens === |

|||

"Inariyama sword, as well as some other swords discovered in Japan, utilized the Korean 'Idu' system of writing." The swords "originated in Paekche and that the kings named in their inscriptions represent Paekche kings rather than Japanese kings." The techniques for making these swords were the same styles from Korea.{{cn|date=October 2014}} |

|||

The oven known as the kamado, popularly referred to as the "Korean oven" in Japan, was originally invented in China but was modified in Korea before being exported to Japan.<ref name="stone"/> According to the historian William Wayne Farris, the introduction of the kamado "had a profound effect on daily life in ancient Japan" and "represented a major advance for residents of Japan's pit dwellings".<ref name="stone"/> The ovens that Japanese people had previously used to cook their meals and heat their homes were less safe, more difficult to use, and less heat efficient.<ref name="stone"/> By the seventh century the kamado was in widespread use in Japan.<ref name="stone"/> |

|||

=== Iron tools and iron metallurgy === |

|||

During the Kofun Period, Korea supplied Japan with most of its iron tools, including chisels, saws, sickles, axes, spades, hoes, and plows.<ref name="tools">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 79-82.</ref> Korean iron farming tools in particular contributed to a rise in Japan's population by possibly 250 to 300 percent.<ref>William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 83.</ref> |

|||

However, it was the refugees who came after 400 from Gaya, a Korean state famous for its iron production, who established some of Japan's first native iron foundries.<ref>Song-Nai Rhee, "Kaya: Korea's Lost Kingdom," ''Korean Culture'', Fall 1999, 8-12.</ref><ref name="gaya"/> The techniques of iron production which they brought to Japan are uniquely Korean and distinct from those used in China.<ref name="armor"/> The work of these Gayan refugees eventually permitted Japan to escape from its dependency on importing iron tools, armor, and weapons from Korea.<ref name="gaya"/> |

|||

=== Dams and irrigation === |

|||

The use of irrigation ponds, a valuable agricultural innovation, were introduced to Japan via Korea around the early to mid-fifth century.<ref name="tools"/> Not long after this Baekje immigrants are credited with engineering Japan's first substantial dam-building project by using native Baekje techniques to construct a series of dams and canals around Kawachi Lake.<ref name="baekje"/> Their objective was to drain the wetlands around the lake and use the land for agriculture.<ref name="baekje"/> A similar project was successfully completed in Kyoto by the descendants of Korean immigrants from Silla.<ref name="clans"/> |

|||

=== Government and administration === |

|||

The centralization of the Japanese state in the sixth and seventh centuries also owes a debt to Korea.<ref name="state">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 443-444.</ref> In 535 the Japanese government established military garrisons called "miyake" throughout Japan to control regional powers and in many cases staffed them with Korean immigrants.<ref name="state"/> Soon after a system of "be", government-regulated groups of artisans, was created, as well as a new level of local administration and a tribute tax. All of these were probably modeled off similar systems used in Baekje and other parts of Korea.<ref name="state"/><ref name="law">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 104-105.</ref> Likewise [[Prince Shotoku]]'s [[Twelve Level Cap and Rank System]] of 603, a form a meritocracy implemented for Japanese government positions, may have been copied directly from the Baekje model.<ref name="state"/> One of the major symbols of the Japanese state's growing power during this period was the palace of [[Emperor Jomei]], which he appropriately called, "Baekje Palace".<ref name="state"/> |

|||

Korean immigrants to Japan also played a role in drafting many important Japanese legal reforms of the era,<ref name="law"/> including the [[Taika Reform]] of 645.<ref>Mikiso Hane, ''Premodern Japan: A Historical Survey'' (Boulder: Westview Press, 1991), 15.</ref> Half of the individuals actively involved in drafting Japan's [[Taiho Code]] of 703 were Korean.<ref name="law"/> |

|||

=== Writing === |

|||

Scribes from the Korean state of Baekje who wrote Chinese introduced writing to Japan in the early fifth century.<ref name="henshall">Kenneth G Henshall, ''A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower'' (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1999), 17, 228.</ref><ref>Marc Hideo Miyake, ''Old Japanese: A Phonetic Reconstruction'' (New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003), 9.</ref><ref>Christopher Seeley, ''A History of Writing in Japan'' (New York: EJ Brill, 1991), 5-6, 23.</ref> The man traditionally credited as being the first to teach writing in Japan is the Baekje scholar [[Wani (scholar)|Wani]].<ref>Mikiso Hane, ''Premodern Japan: A Historical Survey'' (Boulder: Westview Press, 1991), 26.</ref> Though a small number of Japanese people were able to read Chinese before then, it was thanks to the work of scribes from Baekje that the use of writing was popularized among the Japanese governing elite.<ref name="henshall"/> For hundreds of years thereafter a steady stream of talented scribes would be sent from Korea to Japan,<ref>William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 99.</ref> and some of these scholars from Baekje wrote and edited much of the Nihon Shoki, one of Japan's earliest works of history.<ref>Ch'on Kwan-u, "A New Interpretation of the Problems of Mimana (I)," ''Korea Journal'', February 1974, 18.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Wani.jpg|thumb|left|The Korean scholar Wani is credited by ancient sources with introducing written language to Japan]]According to Bjarke Frellesvig, "There is ample evidence, in the form of orthographic 'Koreanisms' in the early inscriptions in Japan, that the writing practices employed in Japan were modelled on continental examples."<ref name="bjarke">Bjarke Frellesvig, ''A History of the Japanese Language'' (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 13.</ref> Japan's [[man'yōgana]] writing system seems to owe a debt to Korea, particularly Baekje,<ref>John R. Bentley, "The Origin of Man'yogana," ''Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies'', February 2001, 62, 72.</ref><ref>Steven Roger Fischer, ''The History of Writing'' (London: Reaktion Books, 2001), 199.</ref> though the transcription systems used in the Samdaemok, an anthology of [[Silla|Sillan]] poetry, and the Japanese [[Manyoshu|Man'yōshu]] also show striking similarities.<ref name="levy">Ian Hideo Levy, ''Hitomaro and the Birth of Japanese Lyricism'' (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 42-43.</ref> In addition, Japanese [[katakana]] share many symbols with Korean [[gugyeol]] suggesting katakana arose in part at least from scribal practices in Korea, though the historical connections between the two systems are obscure.<ref>Ki-moon Lee and S Robert Ramsey, ''A History of the Korean Language'' (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 84.</ref><ref>"朝鮮半島にも「ヲコト点」か 11世紀の経典に似た形態," ''Asahi Shimbun'', December 15 2000, 8.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2002/04/04/national/katakana-system-may-be-korean-professor-says|title=Katakana system may be Korean, professor says|publisher=''Kyodo''|date=April 4, 2002}}</ref> |

|||

=== Science, medicine, and math === |

|||

In 554 Baekje sent Japan a team of learned men including doctors, diviners, and calendar scientists.<ref name="pak">Song-nae Pak, ''Science and Technology in Korean History: Excursions, Innovations, and Issues'' (Fremont, California: Jain, 2005), 42-45.</ref> In 602 the monk [[Gwalleuk]] also reached Japan from Baekje, bringing with him his expert knowledge on astronomy, medicine, and mathematics.<ref name="buswell"/><ref>Lu Gwei-Djen and Joseph Needham, ''Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa'' (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 264.</ref><ref>John Z. Bowers, ''Medical Education in Japan'' (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 3.</ref> Gwalleuk has been credited with being the first person to teach mathematics in Japan.<ref>Alexander Karp and Gert Schubring, ''Handbook on the History of Mathematics Education'' (New York: Springer, 2014), 64.</ref> |

|||

Virtually every astronomer working in seventh century Japan was an immigrants from Korea, mostly Baekje.<ref name="pak"/> Native Japanese astronomers were gradually trained and by the eighth century only forty percent of Japanese astronomers were Korean.<ref name="pak"/> Furthermore, the [[Ishinpō]], a Japanese medical text written in 984, still contains many medical formulas of Korean origin.<ref>Song-nae Pak, ''Science and Technology in Korean History: Excursions, Innovations, and Issues'' (Fremont, California: Jain, 2005), 42-46.</ref> |

|||

During this same period, Japanese farmers divided their arable land using a system of measurement devised in Korea.<ref>William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 105.</ref> |

|||

=== Shipbuilding === |

=== Shipbuilding === |

||

Technicians sent from the Korean kingdom of Silla introduced advanced shipbuilding techniques to Japan for the first time.<ref |

Technicians sent from the Korean kingdom of Silla introduced advanced shipbuilding techniques to Japan for the first time.<ref name="koreanculture"/><ref name="kim"/> Baekje may also have contributed shipbuilding technology to Japan.<ref name="pak"/> |

||

=== |

=== Buddhism === |

||

In the 500s the Korean state of Baekje launched a plan to culturally remake Japan in its own image.<ref name="culture">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 439-440.</ref> It started in the years 513 and 516 when King Muryeong of Baekje dispatched scribes and Confucian scholars to Japan's Yamato court.<ref name="culture"/><ref name="shigeo">Kamata Shigeo, "The Transmission of Paekche Buddhism to Japan," in ''Introduction of Buddhism to Japan: New Cultural Patterns'', eds. Lewis R. Lancaster and CS Yu (Berkeley, California: Asian Humanities Press, 1989), 151-155.</ref> Later King Seong sent Buddhist sutras and a statue of Buddha to Japan, an event described by historian Robert Buswell as "one of the two most critical influences in the entire history of Japan, rivaled only by the nineteenth-century encounter with Western culture."<ref name="buswell">Robert Buswell Jr., "Patterns of Influence in East Asian Buddhism: The Korean Case," in ''Currents and Countercurrents: Korean Influences on the East Asian Buddhist Traditions'', ed. Robert Buswell (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005), 2-4.</ref> The year this occurred, dated by historians to either 538 or 552, marks the official introduction of Buddhism into Japan, and within two years of this date Baekje provided Japan with nine Buddhists priests to aid in propagating the faith.<ref name="culture"/> Buddhism was not universally accepted at first by the Japanese political elite, but following a [[Battle of Shigisan|struggle for power]], the Soga clan established it as Japan's official religion in 587.<ref name="culture"/> |

|||

It has been theorized that [[Yayoi period|Yayoi]] pottery derived from Final [[Jomon period|Jomon]] wares under the influence of the peninsular Korean Plain Pottery tradition.<ref>Mark Hudson, [https://books.google.it/books?id=eTFMPO5NdKgC&pg=PA123 ''Ruins of Identity: Ethnogenesis in the Japanese Islands,''] University of Hawaii Press, 1999, pp.120-123.</ref> Two basic kiln types — both still in use — were employed in Japan by this time. The bank, or climbing, kiln, of Korean origin, is built into the slope of a mountain, with as many as 20 chambers; firing can take up to two weeks. In the updraft, or bottle, kiln, a wood fire at the mouth of a covered trench fires the pots, which are in a circular-walled chamber at the end of the fire trench; the top is covered except for a hole to let the smoke escape. |

|||

Korea continued to supply Japan with Buddhist monks for the remainder of its existence.<ref name="shigeo"/> In 587 the monk P'ungguk arrived from Baekje to serve as a tutor to [[Emperor Yomei]]'s younger brother and later settled down as the first abbot of Japan's [[Shitennō-ji|Shitenno-ji Temple]].<ref name="shigeo"/> In 595 the monk [[Hyeja]] arrived in Japan from Goguryeo.<ref name="best">Jonathan W. Best, "Paekche and the Incipiency of Buddhism in Japan," in ''Currents and Countercurrents: Korean Influences on the East Asian Buddhist Traditions'', ed. Robert Buswell (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005), 31-34.</ref> He became a mentor to Prince Shotoku and lived in [[Asuka-dera|Asuka-dera Temple]].<ref name="best"/> By the reign of the Japanese [[Empress Suiko]] (592-628), there were over one thousand monks and nuns living in Japan, a substantial percentage of whom were Korean.<ref name="shigeo"/> |

|||

In the 17th century CE, Koreans brought the art of [[porcelain]] to Japan.<ref>Emmanuel Cooper, 10,000 Years of Pottery, 2010, University of Pennsylvania Press, p.79</ref> Korean potters also established kilns at [[Karatsu ware|Karatsu]], [[Imari ware|Arita]], [[Satsuma ware|Satsuma]], [[Hagi ware|Hagi]], [[Takatori ware|Takatori]], [[Agano ware|Agano]] and Yatsushiro in Japan.<ref>[http://www.washingtonocg.org/news/2010_02.asp] News - Washington Oriental Ceramic Group (WOCG) : Newsletter {{quote|''In Japan Korean potters were given land and soon created new, advanced kilns in Kyushu -- Karatsu, Satsuma, Hagi, Takatori, Agano and Yatsushiro.''}}</ref><ref name="The Metropolitan Museum of Art">[[#Met|The Met, Muromachi period]] {{quote|''1596 Toyotomi Hideyoshi invades Korea for the second time. In addition to brutal killing and widespread destruction, large numbers of Korean craftsmen are abducted and transported to Japan. Skillful Korean potters play a crucial role in establishing such new pottery types as Satsuma, Arita, and Hagi ware in Japan. The invasion ends with the sudden death of Hideyoshi.''}}</ref><!-- |

|||

A great many Buddhist writings published during Korea's [[Goryeo Dynasty]] (918–1392) were also highly influential upon their arrival in Japan.<ref name="goryeo">Hyoun-jun Lee, "Korean Influence on Japanese Culture (2)," ''Korean Frontier'', September 1970, 20, 31.</ref> Such Korean ideas would play an important role in the development of [[Jōdo Shinshū|Japanese Pure Land Buddhism]].<ref name="buswell"/> The Japanese monk [[Shinran]] was among those known to be influenced by Korean Buddhism, particularly by the [[Silla|Sillan]] monk Gyeongheung.<ref name="buswell"/> |

|||

==== Satsuma ware ==== |

|||

{{See also|Satsuma ware}} |

|||

Robert Buswell notes that the form of Buddhism Korea was propagating throughout its history was "a vibrant cultural tradition in its own right" and that Korea did not serve simply as a "bridge" between China and Japan.<ref name="buswell"/> |

|||

It is documented that during [[Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea]] (1592–1598) Japanese forces abducted a number of Korean craftsmen and artisans, among them a disputed number of potters. Regardless of the number, it is undisputed that at least some Korean potters were forcibly taken to Japan from Korea during the invasions, and that it is the descendants of these potters who started production of pottery in Satsuma.<ref>[[#NYT1901|New York Times (1901)]], paragraph 1</ref> --> |

|||

== Artistic influence == |

|||

According to the scholar Insoo Cho, Korean artwork has had a "huge impact" on Japan throughout history, though until recently the subject was often neglected within academia.<ref>Insoo Cho, "Painters as Envoys: Korean Inspiration in Eighteenth Century Japanese Nanga (Review)," ''Journal of Korean Studies'', Fall 2007, 162.</ref> Beatrix von Ragué has noted that in particular, "one can hardly underestimate the role which, from the fifth to the seventh centuries, Korean artists and craftsmen played in the early art... of Japan."<ref name="lacquer">Beatrix von Ragué, ''A History of Japanese Lacquerwork'' (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976), 5-7.</ref> |

|||

Japanese archaeologists refer to Ono Fortress, Ki Fortress, and the rest as [[Korean-style fortresses in Japan|Korean-style fortresses]]. Because of their close resemblance to the structures built on the peninsula during the same general period. The resemblance is not coincidental. The individuals credited by Chronicles of Japan for building the fortress were all former subjects of the ancient Korean Baekje Kingdom.<ref>Bruce Loyd Batten. Gateway to Japan: Hakata in War And Peace, 500-1300. University of Hawaii Press, 2006, pp.27-28</ref> Especially throughout [[Tenji (period)|Tenji period]], Japanese appear to have favored Baekje fortification experts, putting their technical skills to use in fortifying Japan against a possible foreign invasion.<ref>Michael Como. Shōtoku: Ethnicity, Ritual, and Violence in the Japanese Buddhist Tradition , 2008, p. 26</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Lacquerwork === |

||

[[File:Tamamushi_Shrine_(open_doors).jpg|thumb|right|Tamamushi Shrine]]The first Japanese lacquerwork was produced by or influenced by Korean and Chinese craftsmen in Japan.<ref name="lacquer"/> Most notably is [[Tamamushi Shrine]], a miniature shrine in Horyu-ji Temple, which was created in Korean style, possibly by a Korean immigrant to Japan.<ref name="lacquer"/> Tamamushi Shrine, described by Beatrix von Ragué as "the oldest example of the true art of lacquerwork to have survived in Japan", is decorated with a uniquely-Korean inlay composed of the wings of [[Chrysochroa fulgidissima|tamamushi beetles]].<ref name="lacquer"/> [[Ernest Fenollosa]] has called Tamamushi Shrine, one of the "great monuments of sixth-century Corean art".<ref name="fenollosa">Ernest Fenollosa, ''Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art Volume One'' (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1912), 49-50.</ref> |

|||

The [[Jesuits]] had introduced a Western [[movable type]] [[printing-press]] in [[Nagasaki, Nagasaki|Nagasaki]], [[Japan]] in 1590, worked by two Japanese friars who had learnt type-casting in Portugal. [[Movable type|Moveable type printing]], invented in China in the 11th. century, developed from clay to ceramic, and then bronze copper-tin alloy based movable type presses. Refinements of the technology were further improved in Korea.<ref name=" Donald Keene 1978"/> [[Toyotomi Hideyoshi]] brought over to Japan Korean print technicians and their fonts in 1593 as part of his booty during his [[Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98)|failed invasion of that peninsular (1592-1595).]]<ref>[[Joseph Needham]], [[Tsien Tsuen-Hsuin]], ''Science and Civilisation in China: Vol.5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology,'' Cambridge University Press, 1985 pp.327, 341-342.</ref><ref name="Lane">[[Richard Douglas Lane|Lane, Richard]] (1978). "Images of the Floating World." Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky. P. 33.</ref> That same year, a Korean printing press with movable type was sent as a present for the Japanese Emperor [[Go-Yōzei]]. The emperor commanded that it be used to print an edition of the Confucian [[Classic of Filial Piety|''Classic of Filial Piety'':孝経]].<ref name=" Donald Keene 1978">[[Donald Keene]],''Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era, 1600-1867,'' Grove Press, 1978, p.3.</ref> Four years later in 1597, apparently due to difficulties encountered in casting metal, a Japanese version of the Korean printing press was built with wooden instead of metal type, and in 1599 this press was used to print the first part of the [[Nihon Shoki]] (Chronicles of Japan).<ref name=" Donald Keene 1978"/> |

|||

Japanese lacquerware teabowls, boxes, and tables of the [[Azuchi-Momoyama Period]] (1568–1600) also show signs of Korean artistic influence.<ref name="lacquer1">Beatrix von Ragué, ''A History of Japanese Lacquerwork'' (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976), 176-179.</ref> The mother-of-pearl inlay frequently used in this lacquerware is of clearly Korean origin.<ref name="lacquer1"/> |

|||

== Science == |

|||

In the wake of [[Emperor Kimmei]]'s dispatch of ambassadors to Baekje in 553, several Korean soothsayers, doctors, and calendrical scholars were sent to Japan.<ref>Jacques H. Kamstra, [https://books.google.it/books?id=8sgUAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA60 ''Encounter Or Syncretism: The Initial Growth of Japanese Buddhism,''] Brill Archive, 1967 p.60.</ref> The Baekje Buddhist priest and physician [[Gwalleuk]] came to Japan in 1602, and, settling in the ''Genkōji'' temple(現光寺) where he played a notable role in establishing the [[East Asian Mādhyamaka|Sanron school]],<ref>James H. Grayson, [https://books.google.it/books?id=LU78AQAAQBAJ&pg=PA37 ''Korea - A Religious History,''] Routledge, 2013 p.37.</ref> instructed several court students in the Chinese mathematics of [[astronomy]] and [[calendar|calendrical science]].<ref>Agathe Keller, Alexei Volkov, [https://books.google.it/books?id=MYy9BAAAQBAJ&pg=PA64 'Mathematics Education in Oriental Antiquity and Medieval Ages,'] in Alexander Karp, Gert Schubring (eds.) ''Handbook on the History of Mathematics Education,'' Springer 2014 pp.55-84, p.64.</ref> He introduced the Chinese [[Genka calendar|Yuán Jiā Lì (元嘉暦)]] calendrical system (developed by Hé Chéng Tiān (何承天) in 443 C.E.) and transmitted his skill in medicine and pharmacy to Japanese disciples, such as Hinamitachi (日並立)<ref>[[Gwei-Djen Lu]], [[Joseph Needham]], [https://books.google.it/books?id=WOcLBtm0NHcC&pg=PA264 ''Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa,''] (2002) Routledge, 2012 p.264.</ref><ref>Erhard Rosner, [https://books.google.it/books?id=zddz8ZovLoYC&pg=PA13 ''Medizingeschichte Japans,''] BRILL, 1988 p.13.</ref> |

|||

== |

=== Painting === |

||

The immigration of Korean and Chinese painters to Japan during the Asuka Period transformed Japanese art.<ref name="akiyama">Terukazu Akiyama, ''Japanese Painting'' (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1977), 19-20, 26.</ref> For instance, in the year 610 [[Damjing]], a Buddhist monk from Goguryeo, brought paints, brushes, and paper to Japan.<ref name="akiyama"/> Damjing introduced the arts of papermaking and of preparing pigments to Japan for the first time,<ref name="hyoun">Hyoun-jun Lee, "Korean Influence on Japanese Culture (3)," ''Korean Frontier'', October 1970, 18, 33.</ref><ref name="akiyama"/> and he is also regarded as the artist behind the wall painting in the main hall of Japan's Horyu-ji Temple which was later burned down in a fire.<ref>Song-nae Pak, ''Science and Technology in Korean History: Excursions, Innovations, and Issues'' (Fremont, California: Jain, 2005), 41.</ref> |

|||

In the field of Korean and Japanese music history, it is well known that ancient Korea influenced ancient music of Japan.<ref>Vadime Elisseeff. The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce. UNESCO, 2000, p.270</ref> Since the 5th century, musicians from Korea visited Japan with their music and instruments.<ref name="Lande2007">Liv Lande. Innovating Musical Tradition in Japan: Negotiating Transmission, Identity, and Creativity in the Sawai Koto School. University of California, 2007, pp.62-63</ref> [[Komagaku]], literally "music of Korea", refers to the various types of Japanese court music derived from the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea]] later classified collectively as ''Komagaku''.<ref>Denis Arnold. Oxford Companions Series The New Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press, 1983, p.968</ref> It is made up of purely instrumental music with wind- and stringed instruments(became obsolete), and music which is accompanied by mask dance. Today, Komagaku survives only as [[bugaku|dance]] accompaniment and is not usually performed separately by the [[Imperial Household Agency|Japanese Imperial Household]].<ref>University of California, Los Angeles. Festival of Oriental music and the related arts. Institute of Ethnomusicology, 1973, p.30</ref> |

|||

However, it was during the [[Muromachi Period]] (1337-1573) of Japanese history that Korean influence on Japanese painting reached its peak.<ref name="ink">Ahn Hwi-Joon, "Korean Influence on Japanese Ink Paintings of the Muromachi Period," ''Korea Journal'', Winter 1997, 195-201.</ref> Korean art and artists frequently arrived on Japan's shores, influencing both the style and theme of Japanese ink painting.<ref name="ink"/> The two most important Japanese ink painters of the period were [[Shubun]], whose art displays many of the characteristic features of Korean painting, and Sumon, who was himself an immigrant from Korea.<ref name="ink"/> Consequently, one Japanese historian, Sokuro Wakimoto, has even described the period between 1394 and 1486 as the "Era of Korean Style" in Japanese ink painting.<ref name="ink"/> |

|||

===Instruments=== |

|||

In the 8th century the {{nihongo|''Kudaragoto''|百済琴||extra=literally, "Baekje zither"}}, which resembles the western harp and originated in [[Assyria]], had been introduced from Baekje to Japan along with Korean music.<ref>''Daijisen'' entry for "Kudaragoto".</ref> It has twenty three strings, and was designed to be played in an upright position.<ref>Charles A. Pomeroy. Traditional crafts of Japan. Walker/Weatherhill, 1968</ref>{{Page needed|date=October 2014}} And the 12-string long zither ''Shiragigoto'' was introduced as early as 5th or 6th century from Silla to Japan.<ref name="Lande2007"/> Both fell out of popular use in the early [[Heian period]].<ref>''Daijisen'' entry for "Kudaragoto"; ''Britannica Kokusai Dai-hyakkajiten'' entry for "Shiragigoto".</ref> |

|||

Then during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as a result of the [[Joseon missions to Japan]], the Japanese artists who were developing [[Nanga (Japanese painting)|nanga painting]] came into close contact with Korean artists.<ref name="envoys">Burglind Jungmann, ''Painters as Envoys: Korean Inspiration in Eighteenth-Century Japanese Nanga'' (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 205-211.</ref> Though Japanese nanga received inspiration from many sources, the historian Burglind Jungmann concludes that Korean namjonghwa painting "may well have been the most important for creating the Nanga style."<ref name="envoys"/> It was the Korean brush and ink techniques in particular which are known to have had a significant impact on such Japanese painters as [[Ike Taiga]], Gion Nankai, and Sakaki Hyakusen.<ref name="envoys"/> |

|||

Some instruments in traditional Japanese music originated in Korea: [[Komabue]] is a six-hole traverse flute of Korean origin.<ref>William P. Malm. Traditional Japanese Music and Musical Instruments. Kodansha International, 2000, p.109</ref> It is used to perform Komagaku and ''Azuma asobi''<ref>Ben no Naishi, Shirley Yumiko Hulvey, Kōsuke Tamai. Sacred rites in moonlight. East Asia Program Cornell University, 2005, p.202</ref>(chants and dances, accompanied by an ensemble pieces). [[San-no-tsuzumi]] is an hourglass-shaped drum of Korean origin.<ref>William P. Malm. Traditional Japanese Music and Musical Instruments. Kodansha International, 2000, p.93</ref><ref>Shawn Bender, Taiko Boom: Japanese Drumming in Place and Motion. University of California Press, 2012, p.27</ref> The drum has two heads, which are struck using a single stick. It is played only in Komagaku. |

|||

== |

=== Music and dance === |

||

In ancient times the imperial court of Japan imported all its music from abroad, though it was Korean music that reached Japan first.<ref name="music">William P. Malm, ''Traditional Japanese Music and Musical Instruments'' (New York: Kodansha International, 1959), 33, 98-100, 109.</ref> The first Korean music may have infiltrated Japan as early as the third century.<ref name="music"/> Korean court music in ancient Japan was at first called "sankangaku" in Japanese, referring to music from all the states of the Korean peninsula, but it was later termed "komagaku" in reference specifically to the court music of the Korean kingdom of Guguryeo.<ref name="music"/> According to Professor Song Bang-song, it was not the case that Korean music influenced Japanese music, but rather than Japan simply adopted Korean music in toto.<ref>Song Bang-song, "The Exchange of Musical Influences between Korea and Central Asia," in ''The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce'', ed. Vadime Elisseeff (New York: Berghahn Books, 2000), 270.</ref> |

|||

Many Japanese myths about the age of the gods are believed by scholars including [[Mikiso Hane]] and Joo-Young Yoo{{who|date=May 2015}}<!-- This person was a college student (possibly a graduate student but may even have been an undergrad) at the time he wrote the essay in question -- is he a "scholar"? We should probably remove his name altogether, methinks. ~Hijiri88, May 2015. --> to have their origins in Korean stories.<ref>Premodern Japan: A Historical Survey by Mikiso Hane page 23</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://web.archive.org/web/20030217053544/http://www.aad.berkeley.edu/uga/osl/mcnair/94BerkeleyMcNairJournal/07_Yoo.html|title=Foundation and Creation Myths in Korea and Japan: Patterns and Connections|author=Joo-Young Yoo|publisher=''McNair Journal''|year=1994|accessdate=December 13, 2014}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Komabue_fue.jpg|thumb|right|Komabue, a Korean flute used in early Japanese court music]]Musicians from various Korean states often went to work in Japan.<ref name="music"/><ref name="culture"/> Mimaji, a Korean entertainer from Baekje, introduced Chinese dance and Chinese [[gigaku]] music to Japan in 612.<ref name="music"/><ref>Martin Banham, ''The Cambridge Guide to World Theatre'' (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 559.</ref> By the time of the [[Nara Period]] (710-794), every musician in Japan's imperial court was either Korean or Chinese.<ref name="music"/> Korean musical instruments which became popular in Japan during this period include the flute known as the [[komabue]], the zither known as the [[gayageum]], and the harp known as the shiragikoto.<ref name="koreanculture">Hyoun-jun Lee, "Korean Influence on Japanese Culture (1)," ''Korean Frontier'', August 1970, 12, 29.</ref><ref name="music"/> |

|||

Concerning literature, [[Roy Andrew Miller]] has stated that, "Japanese scholars have made important progress in identifying the seminal contributions of Korean immigrants, and of Korean literary culture as brought to Japan by the early Korean diaspora from the Old Korean kingdoms, to the formative stages of early Japanese poetic art".<ref>Roy Andrew Miller, "Plus Ça Change...," ''The Journal of Asian Studies'', August 1980, 776.</ref> For example, the [[Man'yoshu| Man'yō poet]] [[Yamanoue no Okura]] is widely thought to be of foreign descent.<ref>Edwin A. Cranston, ' Asuka and Nara culture: literacy, literature, and music,' in [[John Whitney Hall]] (ed.),[https://books.google.it/books?id=A3_6lp8IOK8C&pg=PA479 ''The Cambridge History of Japan,''] Cambridge University Press Vol.1, 1993 p.p453-503, p.479.</ref> [[Susumu Nakanishi]] has argued that Okura was born in the Korean kingdom of [[Baekje|Kudara]] to a high court doctor and came with his émigré family to Yamato at the age of 3 after the collapse of that kingdom. It has been noted that the Korean genre of [[hyangga|hyangga (郷歌)]], of which only 25<ref name="LeeRamsey" /> examples survive from the [[Silla]] kingdom's Samdaemok (三代目), compiled in 888 CE., differ greatly in both form and theme from the Man'yō poems, with the single exception of some of Yamanoue no Okura's poetry which shares their Buddhist-philosophical thematics.<ref name="Levy" >[[Hideo Levy|Ian Hideo Levy]], [https://books.google.it/books?id=k8__AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA43 ''Hitomaro and the Birth of Japanese Lyricism,''] Princeton University Press, 1984 pp.42-43.</ref> Roy Andrew Miller, arguing that Okura's 'Korean ethnicity' is an established fact though one disliked by the Japanese literary establishment, speaks of his 'unique binational background and multilingual heritage'.<ref>Roy Andrew Miller, 'Uri Famëba,' in Stanca Scholz-Cionca (ed.),[https://books.google.it/books?id=2ur1zGDUW78C&pg=PA85 ''Wasser-Spuren: Festschrift für Wolfram Naumann zum 65. Geburtstag,''] Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1997 pp.85-104, pp.85-6, p.104.</ref> |

|||

Though much has been written about Korean influence on early Japanese court music, Taeko Kusano has stated that Korean influence on Japanese folk music during the [[Edo Period]] (1603-1868) represents a very important but neglected field of study.<ref name="folk">Taeko Kusano, "Unknown Aspects of Korean Influence on Japanese Folk Music," ''Yearbook for Traditional Music'', 1983, 31-36.</ref> According to Taeko Kusano, each of the Joseon missions to Japan included about fifty Korean musicians and left their mark on Japanese folk music. Most notably, the "tojin procession", which was practiced in [[Nagasaki]], the "tojin dance", which arose in modern-day [[Mie Prefecture]], and the "karako dance", which exists in modern-day [[Okayama Prefecture]], all have Korean roots and utilize Korean-based music.<ref name="folk"/> |

|||

Several [[Zainichi Koreans]] have been active on the Japanese literary scene starting in the latter half of the twentieth century.<!-- This comes from Levy 2010 "The World in Japanese" (lecture) Stanford University YouTube channel, but a better source can probably be found. ~Hijiri88, May 2015. --> |

|||

== |

=== Silk weaving === |

||

Silk weaving took off in Japan from the fifth century onward as a result of new technology brought from Korea.<ref name="silk">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 97.</ref> Japan's Hata clan, who immigrated from Korea, are believed to have been specialists in the art of silk weaving and silk tapestry.<ref name="silk"/> |

|||

During the [[Asuka Period]] of Japan, immigrant scholars, monks and communities from the Korean kingdom of [[Baekje]] brought Buddhism in their train,<ref>Jacques H. Kamstra, [https://books.google.it/books?id=NRsVAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA464 ''Encounter Or Syncretism: The Initial Growth of Japanese Buddhism,''] Brill Archive, 1967 p.464.</ref> and served both as teachers and as advisers to Japan's rulers.<ref name="Kodansha encyclopedia of Japan"/> In the traditional account, in 545, King [[Seong of Baekje]] is said to sent a Buddhist statue and copies of the Sanskrit scriptures to the Japanese court. Seven years later, in 552, he had a bronze statue cast, which, together with a stone statue of [[Maitreya]], and Buddhist sutras, he send to the ruler of Japan. The gift was accompanied by a letter advising that he adopt Buddhism as superior to Confucianism, since it was more broadly accepted in India, China and Baekje.<ref>James Huntley Grayson, [https://books.google.it/books?id=aX8eAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA27 ''Early Buddhism and Christianity in Korea: A Study in the Emplantation of Religion,''] BRILL, 1985 p.27.</ref> After the initial entrance of some craftsmen, scholars, and artisans from Baekje, [[Emperor Kimmei]] is said to have requested Korean men who were skilled in divination, calendar making, medicine and literature.<ref name="Mircea Eliade">Mircea Eliade, Charles J. Adams. The Encyclopedia of religion, Volume 9. Macmillan, 1987</ref> The origins of the [[Soga clan]], which played a major role in the introduction of Buddhism into Japan, are shrouded in obscurity. An unorthodox view, associated with Kadowaki Teiji (門脇禎二), argued that a certain Machi, whom he assumed was the clan's real founder, had been a Korean nobleman (Moku Machi) who emigrated to Japan around 475. What is generally accepted is that the Soga had close links, ancestral or otherwise, with the Paekje elite.<ref> Donald Fredrick McCallum, [https://books.google.it/books?id=OAyk-ObsD6sC&pg=PA19 ''The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh Century Japan,''] University of Hawaii Press, 2009 pp.19f.</ref> Scholars who have argued in favor of the theory that the Soga had Korean ancestry include Song-Nai Rhee, C. Melvin Aikens, Sung-Rak Choi, Hyuk-Jin Ro, and William Wayne Farris.<ref>Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 439-440.</ref><ref>William Wayne Farris, ''Japan to 1600: A Social and Economic History'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009), 25.</ref> |

|||

== |

=== Jewelry === |

||

Japan at first imported jewelry made of glass, gold, and silver from Korea, but in the fifth century the techniques of gold and silver metallurgy also entered Japan from Korea, possibly from the Korean states of Baekje and Gaya.<ref name="jewelry">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 96, 118.</ref> Korean immigrants established important sites of jewelry manufacturing in [[Katsuragi, Nara|Katsuragi]], [[Gunma]], and other places in Japan, allowing Japan to domestically produce its first gold and silver earrings, crowns, and beads.<ref name="other">Song-Nai Rhee et al., "Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan," ''Asian Perspectives'', Fall 2007, 441, 443.</ref> |

|||

It has often been held that [[Edo Neo-Confucianism]] was built on foundations laid by Korean scholars. According to this theory, [[Kang Hang]], who had been captured by Hideyoshi's forces and brought to Japan, and [[Yi Hwang|Yi T'oegye]] played a signal role, the latter's works gaining a high repute among Japanese scholars of the Tokugawa period, where his influence was profound and lasting.<ref>Edward Y. J. Chung, [[Yi Hwang/T’oegye]] [https://books.google.it/books?id=ZIuQgtZd4FAC&pg=PA22 ''The Korean Neo-Confucianism of Yi T'oegye and Yi Yulgok: A Reappraisal of the 'Four-Seven Thesis' and its Practical Implications for Self-Cultivation,''] SUNY Press, 1995 p.22</ref><ref>Seizaburo Sato, 'Response to the West: The Korean and Japanese Patterns,' in Albert M. Craig (ed.),[https://books.google.it/books?id=W1x9BgAAQBAJ&pg=PA108 ''Japan: A Comparative View,''] Princeton University Press, 1979 pp.105.128 p.108.</ref> The theory is regarded as questionable, after being rebutted by Willem van Boot in his 1982 doctoral thesis: 'A similar great transformation in Japanese intellectual history has also been traced to Korean sources, for it has been asserted that the vogue for neo-Confucianism, a school of thought that would remain prominent throughout the Edo period (1600-1868), arose in Japan as a result of the Korean war, whether on account of the putative influence that the captive scholar-official Kang Hang exerted on Fujiwara Seika (1561-16519), the ''soi-disant'' discoverer of the true Confucian tradition for Japan, or because Korean books from looted libraries provided the new pattern and much new matter for a redefinition of Confucianism. this assertion, however is questionable and indeed has been rebutted convincingly in recent Western scholarship.' <ref>Jurgis Elisonas, 'The inseparable trinity: Japan's relations with China and Korea' [https://books.google.it/books?id=ycdGHcKLcd8C&pg=PA293 ''Early Modern Japan,'' ] The Cambridge History of Japan, vol.4 Cambridge University Press 1991 pp.235-300. p.293.</ref> |

|||

== Law == |

|||

Korean influence on Japanese laws is also attributed to the fact that Korean immigrants were on committees that drew up law codes. There were Chinese immigrants who were also an integral part in crafting Japan's first laws. Eight of the 19 members of the committee drafting the Taihō Code were from Korean immigrant families while none were from China proper. Furthermore, the structuring of local administrative districts and the tribute tax are based on Korean models.<ref>{{cite book| url=http://books.google.com/books?ie=UTF-8&vid=ISBN0824820304&id=dCNioYQ1HfsC&vq=yamato+paekche&dq=kofun+tumuli+korea&lpg=PA104&pg=PA105&sig=3Me7_8p9Tdh1KAYJFUpG7L-Q8ho| title=Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues on the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan| first=William Wayne| last=Farris| pages=105| isbn=0-8248-2030-4| publisher=University of Hawaii Press}}</ref> |

|||

== |

=== Sculpture === |

||

Along with Buddhism, the art of Buddhism sculpture also spread to Japan from Korea.<ref name="donald">Donald McCallum, "Korean Influence on Early Japanese Buddhist Sculpture," ''Korean Culture'', March 1982, 22, 26, 28.</ref> At first almost all Japanese Buddhist sculptures were imported from Korea, and these imports demonstrate an artistic style which would dominate Japanese sculpture during the [[Asuka Period]] (538-710).<ref name="donald"/> In the years 577 and 588 the Korean state of Baekje dispatched to Japan expert statue sculptors.<ref name="baekje">William Wayne Farris, ''Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan'' (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998), 102-103.</ref> |

|||

[[Chinese characters]] are generally used to represent meaning (as [[ideogram]]s), but have also been used to phonetically represent words in non-Chinese languages such as [[Korean language|Korean]] and [[Japanese language|Japanese]]. The practice of using Chinese characters to represent the sounds of non-Chinese words was probably first developed in China during the [[Han Dynasty]], often to transcribe [[Sanskrit]] terms used by Buddhists. This practice spread to the Korean Peninsula during the [[Three Kingdoms of Korea|Three Kingdoms period]], initially through [[Goguryeo]], and later to [[Silla]] and [[Baekje]]. These phonograms were used extensively to write local place-names in ancient Korea. According to Bjarke Frellesvig, "There is ample evidence, in the form of orthographic 'Koreanisms' in the early inscriptions in Japan, that the writing practices employed in Japan were modelled on continental examples.<ref>{{cite book|last=Frellesvig|first=Bjarke|title=A History of the Japanese Language|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=v1FcAgiAC9IC&pg=PA160|date=2010-07-29|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-139-48880-8|page=13}}</ref> |

|||