Völundarkviða: Difference between revisions

Anonymous44 (talk | contribs) Undid revision 798436299 by 24.91.248.60 (talk) I am neither blocked nor evading anything. |

Alarichall (talk | contribs) synopsis made more detailed, and a section on provenance added |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Italic title}} |

|||

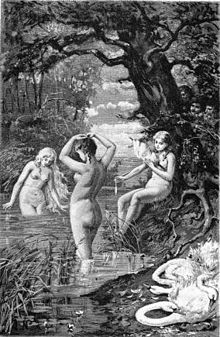

[[File:Valkyries with swan skins.jpg|thumb|[[Völundr]] and his two brothers see the swan-maidens bathing. Illustration by [[Jenny Nyström]], 1893.]] |

[[File:Valkyries with swan skins.jpg|thumb|[[Völundr]] and his two brothers see the swan-maidens bathing. Illustration by [[Jenny Nyström]], 1893.]] |

||

[[File:Die drei Schmeideburschen belauschen und gewinnen drei Walkürenjungfrauen by W. Heine.jpg|thumb|"The three smith boys spy and later marry three valkyrie maidens" (1882) by [[Friedrich Wilhelm Heine]].]] |

[[File:Die drei Schmeideburschen belauschen und gewinnen drei Walkürenjungfrauen by W. Heine.jpg|thumb|"The three smith boys spy and later marry three valkyrie maidens" (1882) by [[Friedrich Wilhelm Heine]].]] |

||

'''''Völundarkviða''''' |

'''''Völundarkviða''''' (modern Icelandic spelling) or '''''Vǫlundarkviða''''' (standardised Old Norse spelling) [''Völundr's poem''] is one of the mythological poems of the ''[[Poetic Edda]]''. The title can be [[Old Norse orthography|anglicized]] as ''Völundarkvitha'', ''Völundarkvidha'', ''Völundarkvida'', ''Volundarkvitha'', ''Volundarkvidha'' or ''Volundarkvida''). |

||

==Manuscripts, origins, and analogues== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The vocabulary and some of the [[Oral-formulaic composition|formulaic phrasing]] of the poem is clearly influenced by [[West Germanic]], with the strongest case being for influence from [[Old English]] (as West Germanic language). It is thought likely, therefore, that the poem was composed in or otherwise influenced by traditions from the [[Danelaw|Norse diaspora in England]]. This would suggest origins around the tenth or eleventh century.<ref>John McKinnell, ‘[http://www.vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Saga-Book%201-22%20searchable/Saga-Book%20XXIII.pdf The Context of ''Vǫlundarkviða'']’, ''Saga-Book of the Viking Society'', 23 (1990), 1–27.</ref><ref>John McKinnell, ‘Eddic Poetry in Anglo-Scandinavian Northern England’, in ''Vikings and the Danelaw: Select Papers from the Proceedings of the Thirteenth Viking Congress, Nottingham and York, 21-30 August 1997'', ed. by James Graham-Campbell, Richard Hall, Judith Jesch and David N. Parsons (Oxford: Oxbow, 2001), pp. 327–44.</ref> This fits in turn with the fact that most of the analogues to ''Vǫlundarkviða'' are West-Germanic in origin. |

|||

In visual sources, the story told in ''Vǫlundarkviða'' seems to be portrayed on the front panel of the eighth-century Northumbrian [[Franks Casket]] and on the eighth-century [[Gotland]]ic [[Ardre image stone]] VIII, along with a number of tenth-to-eleventh-century carvings from Northern England, including the [[Leeds Cross Shaft]].<ref>James T. Lang, ‘Sigurd and Weland in Pre-Conquest Carving from Northern England’, ''The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal'', 48 (1976), 83–94.</ref> In written sources, a largely similar story (''[[Velents þáttr smiðs]]'') is related in the Old Norse ''[[Þiðrekssaga af Bern]]'' (translated from lost [[Low German language|Low German]] sources. And an evidently similar story is alluded to in the [[Old English language|Old English]] poem ''[[Deor|The Lament of Deor]]''.<ref>''The Poetic Edda. Volume II, Mythological Poems'', ed. and trans. by Ursula Dronke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 269-84.</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+ |

|||

! colspan="3" |Equivalent character names |

|||

|- |

|||

!''Vǫlundarkviða'' |

|||

!''Dēor'' |

|||

!''Þiðreks saga'' |

|||

|- |

|||

|Vǫlundr |

|||

|Wēlund |

|||

|Velent |

|||

|- |

|||

|Níðuðr |

|||

|Nīðhād |

|||

|Níðungr |

|||

|- |

|||

|Bǫðvildr |

|||

|Beaduhild |

|||

|unnamed |

|||

|} |

|||

==Synopsis== |

==Synopsis== |

||

The poem relates the story of the artisan [[Wayland the Smith|Völundr]], his capture [[Níðuðr]], implicitly a petty-king of [[Närke]] (Sweden), and Vǫlundr's brutal revenge and escape.<ref>The synopsis is based on Alaric Hall, ''[https://libgen.pw/item/detail/id/383363?id=383363 Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity]'', Anglo-Saxon Studies, 8 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007), p. 40.</ref> |

|||

The poem relates the story of the artisan [[Wayland the Smith|Völundr]]. In the poem, he is called "prince of the [[álfar|elves]]" (''vísi álfa'') and "one of the ''álfar''" or "leader of ''álfar''" (''álfa ljóði''). He is also mentioned as one of the three sons of the king of the Finns in the poem. His wife ''Hervör-Alvitr'', a [[valkyrie]], abandons him after nine years, and he is later captured by [[Níðuðr]], a petty-king of [[Närke]] (Sweden) greedy for his gold. Völundr is [[Hamstringing|hamstrung]] and put to work on an island making artifacts for the king. Eventually he finds means of revenge and escape. He kills Niðuðr's sons, impregnates his daughter and then flies away laughing. |

|||

====Prose introduction==== |

|||

''Vǫlundarkviða'' begins with a prose introduction, setting the scene, giving background about the characters, and partly summarising the poem. It is possible that this passage is much younger than the verse. |

|||

====Stanzas 1–6==== |

|||

The poem opens by describing the flight of three [[Swan maiden|swan-maidens]] identified in stanza 1 as ''meyjar'', ''drósir'', ''alvitr'' and ''suðrœnar'' ('young women, stately women, foreign beings, southerners') to a 'sævar strǫnd' ('lake/sea-shore') where they meet the three brothers [[Egil, brother of Volund|Egill]], [[Slagfiðr]] and Vǫlundr. Each maid takes one of the brothers as her own. |

|||

However, nine winters later, the women leave the brothers. The poem does not explain this, simply saying that the women depart 'ørlǫg drýgja' ('to fulfil their fate'). Slagfiðr and Egill go in search of their women, but Vǫlundr remains at home instead, forging ''baugar'' (‘(arm-)rings’) for his woman. |

|||

====Stanzas 7–19==== |

|||

Discovering that Vǫlundr is living alone, a local king, Níðuðr, ‘lord of the [[Njárar]]’, has him captured in his sleep |

|||

(stanzas 7–12). |

|||

Níðuðr takes Vǫlundr’s sword and gives one of the rings which Vǫlundr made for his missing bride to his daughter [[Böðvildr|Bǫðvildr]], and, at his wife’s instigation, he has Vǫlundr’s hamstrings cut, imprisoning him on an island called Sævarstaðr, where Vǫlundr makes objects for Níðuðr (stanzas 13–19). |

|||

====Stanzas 20–41==== |

|||

Vǫlundr takes his revenge on Níðuðr first by enticing his two sons to visit with promises of treasure, killing them, and making jewels of their eyes and teeth (stanzas 20–26). He then entices Bǫðvildr by promising to mend the ring which she was given, getting her drunk, and implicitly having sex with her (stanzas 27–29). |

|||

The poem culminates in Vǫlundr taking to the air by some means which is not clearly described and telling Níðuðr what he has done, laughing (stanzas 30–39). It focuses finally on the plight of Bǫðvildr, whose lament closes the poem (stanzas 40–41): |

|||

{{Verse translation| |

|||

{{lang|is|Ek vætr hánom |

|||

vinna kunnak, |

|||

ek vætr hánom |

|||

vinna máttak.<ref>''The Poetic Edda. Volume II, Mythological Poems'', ed. and trans. by Ursula Dronke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 254.</ref>}} |

|||

| |

|||

I did not know how to |

|||

struggle against him at all, |

|||

I was not able to |

|||

struggle against him at all.}} |

|||

== Literary criticism == |

|||

The poem is appreciated for its evocative images. |

The poem is appreciated for its evocative images. |

||

| Line 12: | Line 76: | ||

:their shields glistened |

:their shields glistened |

||

:in the waning moon. |

:in the waning moon. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:Völund on ardre 01.png|thumb|right|180px|Völund's smithy in the centre, Nidud's daughter to the left, and Nidud's dead sons hidden to the right of the smithy. Between the girl and the smithy, Völund can be seen flying away with eagle wings. From the [[Ardre image stone]] VIII.]] |

|||

The Völundr myth appears to have been widespread among the Germanic peoples. It is also related in the ''[[Þiðrekssaga af Bern]]'' (''[[Velents þáttr smiðs]]'') and it is alluded to in the [[Old English language|Old English]] poem ''[[Deor|The Lament of Deor]]''. It is moreover depicted on a panel of the 7th century Anglo-Saxon [[Franks Casket]] and on the 8th century [[Gotland]]ic [[Ardre image stone]] VIII. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

Revision as of 21:43, 30 October 2018

Völundarkviða (modern Icelandic spelling) or Vǫlundarkviða (standardised Old Norse spelling) [Völundr's poem] is one of the mythological poems of the Poetic Edda. The title can be anglicized as Völundarkvitha, Völundarkvidha, Völundarkvida, Volundarkvitha, Volundarkvidha or Volundarkvida).

Manuscripts, origins, and analogues

The poem is preserved in its entirety among the mythological poems of the thirteenth-century Icelandic manuscript Codex Regius, and the beginning of the prose prologue is also found in the AM 748 I 4to fragment.

The vocabulary and some of the formulaic phrasing of the poem is clearly influenced by West Germanic, with the strongest case being for influence from Old English (as West Germanic language). It is thought likely, therefore, that the poem was composed in or otherwise influenced by traditions from the Norse diaspora in England. This would suggest origins around the tenth or eleventh century.[1][2] This fits in turn with the fact that most of the analogues to Vǫlundarkviða are West-Germanic in origin.

In visual sources, the story told in Vǫlundarkviða seems to be portrayed on the front panel of the eighth-century Northumbrian Franks Casket and on the eighth-century Gotlandic Ardre image stone VIII, along with a number of tenth-to-eleventh-century carvings from Northern England, including the Leeds Cross Shaft.[3] In written sources, a largely similar story (Velents þáttr smiðs) is related in the Old Norse Þiðrekssaga af Bern (translated from lost Low German sources. And an evidently similar story is alluded to in the Old English poem The Lament of Deor.[4]

| Equivalent character names | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vǫlundarkviða | Dēor | Þiðreks saga |

| Vǫlundr | Wēlund | Velent |

| Níðuðr | Nīðhād | Níðungr |

| Bǫðvildr | Beaduhild | unnamed |

Synopsis

The poem relates the story of the artisan Völundr, his capture Níðuðr, implicitly a petty-king of Närke (Sweden), and Vǫlundr's brutal revenge and escape.[5]

Prose introduction

Vǫlundarkviða begins with a prose introduction, setting the scene, giving background about the characters, and partly summarising the poem. It is possible that this passage is much younger than the verse.

Stanzas 1–6

The poem opens by describing the flight of three swan-maidens identified in stanza 1 as meyjar, drósir, alvitr and suðrœnar ('young women, stately women, foreign beings, southerners') to a 'sævar strǫnd' ('lake/sea-shore') where they meet the three brothers Egill, Slagfiðr and Vǫlundr. Each maid takes one of the brothers as her own.

However, nine winters later, the women leave the brothers. The poem does not explain this, simply saying that the women depart 'ørlǫg drýgja' ('to fulfil their fate'). Slagfiðr and Egill go in search of their women, but Vǫlundr remains at home instead, forging baugar (‘(arm-)rings’) for his woman.

Stanzas 7–19

Discovering that Vǫlundr is living alone, a local king, Níðuðr, ‘lord of the Njárar’, has him captured in his sleep (stanzas 7–12).

Níðuðr takes Vǫlundr’s sword and gives one of the rings which Vǫlundr made for his missing bride to his daughter Bǫðvildr, and, at his wife’s instigation, he has Vǫlundr’s hamstrings cut, imprisoning him on an island called Sævarstaðr, where Vǫlundr makes objects for Níðuðr (stanzas 13–19).

Stanzas 20–41

Vǫlundr takes his revenge on Níðuðr first by enticing his two sons to visit with promises of treasure, killing them, and making jewels of their eyes and teeth (stanzas 20–26). He then entices Bǫðvildr by promising to mend the ring which she was given, getting her drunk, and implicitly having sex with her (stanzas 27–29).

The poem culminates in Vǫlundr taking to the air by some means which is not clearly described and telling Níðuðr what he has done, laughing (stanzas 30–39). It focuses finally on the plight of Bǫðvildr, whose lament closes the poem (stanzas 40–41):

Ek vætr hánom |

I did not know how to |

Literary criticism

The poem is appreciated for its evocative images.

- In the night went men,

- in studded corslets,

- their shields glistened

- in the waning moon.

Völundarkviða 6, Thorpe's translation

References

- ^ John McKinnell, ‘The Context of Vǫlundarkviða’, Saga-Book of the Viking Society, 23 (1990), 1–27.

- ^ John McKinnell, ‘Eddic Poetry in Anglo-Scandinavian Northern England’, in Vikings and the Danelaw: Select Papers from the Proceedings of the Thirteenth Viking Congress, Nottingham and York, 21-30 August 1997, ed. by James Graham-Campbell, Richard Hall, Judith Jesch and David N. Parsons (Oxford: Oxbow, 2001), pp. 327–44.

- ^ James T. Lang, ‘Sigurd and Weland in Pre-Conquest Carving from Northern England’, The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, 48 (1976), 83–94.

- ^ The Poetic Edda. Volume II, Mythological Poems, ed. and trans. by Ursula Dronke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), pp. 269-84.

- ^ The synopsis is based on Alaric Hall, Elves in Anglo-Saxon England: Matters of Belief, Health, Gender and Identity, Anglo-Saxon Studies, 8 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2007), p. 40.

- ^ The Poetic Edda. Volume II, Mythological Poems, ed. and trans. by Ursula Dronke (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 254.

- Dronke, Ursula (Ed. & trans.) (1997). The Poetic Edda, vol. II, Mythological Poems. Oxford: Clarendeon. ISBN 0-19-811181-9.

- Thorpe, Benjamin. (Trans.). (1866). Edda Sæmundar Hinns Froða: The Edda Of Sæmund The Learned. (2 vols.) London: Trübner & Co. 1866. Reprinted 1906 as Rasmus B. Anderson & J. W. Buel (Eds.) The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson. London, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Berlin, New York: Norrœna Society. Available online at Google Books. Searchable graphic image version requiring DjVu plugin available at University of Georgia Libraries: Facsimile Books and Periodicals: The Elder Eddas and the Younger Eddas.

External links

English translations

- Völundarkvitha Translation and commentary by Henry Adams Bellows

- Bellows' translation with facing page Old Norse text

- Translation by Benjamin Thorpe

- Völundarkviða Translation by W. H. Auden and P. B. Taylor

Old Norse editions

- Völundarkviða Sophus Bugge's edition of the manuscript text

- Völundarkviða Guðni Jónsson's edition with normalized spelling