12th Light Horse Regiment (Australia): Difference between revisions

Anotherclown (talk | contribs) m typo |

expand |

||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

[[File:4th Light Horse Brigade Beersheba.jpg|thumb|alt=Mounted soldiers charge towards the camera over rocky ground|Light horse charge]] |

[[File:4th Light Horse Brigade Beersheba.jpg|thumb|alt=Mounted soldiers charge towards the camera over rocky ground|Light horse charge]] |

||

| ⚫ | The regiment's next major action did not come until October 1917 when it took part in the [[Battle of Beersheba (1917)|fighting around Beersheba]],<ref name=AWM/> which was conceived as part of a third attempt to capture Gaza. During this battle, along with the 4th Light Horse Regiment, the 12th carried out a famously successful mounted charge, advancing over open ground late in the afternoon to get under the Ottoman guns and capture the town and its vital water supplies.<ref>{{harvnb|Coulthard-Clark|1998|pp=134–135}}.</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Perry|2009|pp=318–323}}.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The regiment's next major action did not come until October 1917 when it took part in the [[Battle of Beersheba (1917)|fighting around Beersheba]],<ref name=AWM/> which was conceived as part of a third attempt to capture Gaza. During this battle, along with the 4th Light Horse Regiment, the 12th carried out a famously successful mounted charge, advancing over open ground late in the afternoon to get under the Ottoman guns and capture the town and its vital water supplies.<ref>{{harvnb|Coulthard-Clark|1998|pp=134–135}}.</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Perry|2009|pp=318–323}}.</ref> Late in the afternoon, advancing on the left of the 4th, the 12th Light Horse Regiment advanced on a "squadron frontage in three lines" from {{convert|300|-|500|yd|m}} and together they launched a "pure cavalry" charge with the soldiers advancing with bayonets in their hands.<ref>{{harvnb|Gullett|1941|p=395}}</ref> Advancing over {{convert|6,000|m|yd}},<ref>{{harvnb|Coulthard-Clark|1998|p=135}}.</ref> the light horsemen were subjected to rifle and machine-gun fire and artillery bombardment from the flanks and trenches to their front. Supporting artillery helped suppress the machine-gun fire from the flanks,<ref>{{harvnb|Gullett|1941|p=396}}.</ref> and the speed of the charge made it difficult for the Ottoman gunners to adjust their range. The Ottoman trenches were not protected with wire and after jumping over the trenches, the light horsemen dismounted and hand-to-hand fighting followed.<ref>{{harvnb|Coulthard-Clark|1998|pp=135–136}}.</ref> The battle was a stunning success with over 700 Ottoman soldiers captured and, more significantly for the Australians, over 400,000 litres of water secured. But it came at a price for the 12th who lost 24 men killed and 15 wounded;<ref>{{harvnb|Hollis|2008|p=59}}.</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Gullett|1941|p=401}}.</ref> the regiment also lost 44 horses killed in action, while another 60 were wounded or became sick.<ref>{{harvnb|Hollis|2008|p=60}}.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The success at Beersheeba significantly reduced Ottoman resistance and steadily they began to fall back with the British Empire troops following them in pursuit.<ref name=AWM/> |

||

| ⚫ | The success at Beersheeba significantly reduced Ottoman resistance and steadily they began to fall back with the British Empire troops following them in pursuit.<ref name=AWM/> The regiment remained at Beersheeba for four days where they received remounts, and then throughout November the regiment advanced further into Palestine as part of the plan to [[Battle of Jerusalem (1917)|capture Jerusalem]]. Advancing towards Khurbet Buteihah, the regiment took part in an engagement around Sheria on 7 November, but was forced to call a halt to their charge as their horses needed water, and amidst artillery and machine-gun fire, the regiment dismounted.<ref>{{harvnb|Gullett|1941|p=432}}.</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Hollis|2008|pp=62–63}}.</ref> The following day, the 12th was sent to Beit Hanun to contact the Imperial Service Cavalry brigade, before searching for water around Sin Sin and [[Al-Faluja|Faluje]], where they captured a number of Ottoman troops before rejoining the [[Australian Mounted Division]] at [[Huj]]. On 10 November, the 12th provided support to the 11th Light Horse Regiment when they came under attack at Hill 248 by a strong Ottoman counterattack, which was turned back.<ref>{{harvnb|Hollis|2008|p=63}}</ref> After moving on to [[Summil|Summeil]], they entered Et Tine on 14 November without firing a shot, securing a water source and a large amount of supplies, although a large amount of equipment was lost to a fire which had been set by the withdrawing garrison.<ref>{{harvnb|Gullett|1941|p=473}}</ref> The 12th then took up an observation position at El Dhenebbe to support the British flank before moving to Wadi Menakh on 18 November to water their horses. They were then ordered to launch an attack around Abu Shushen, but were recalled before it began and amidst heavy rain camped at Deiran. Three days later, the 12th encamped at Mejdel for a week of rest along with the majority of its division.<ref>{{harvnb|Hollis|2008|pp=63–64}}</ref> After a brief respite, as the 4th Light Horse Brigade was sent to El Burj to relieve British forces there, the 12th went in to reserve; the horses were sent back to Deiran, and dismounted patrols and reconnaissance parties were sent out.<ref>{{harvnb|Hollis|2008|p=64}}.</ref> |

||

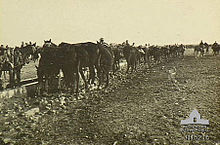

[[File:AWM H15216 12th Light Horse at Beersheba 1917.jpg|right|thumb|Horses from the 12th Light Horse Regiment drink at Beersheba |alt=A line of horses drink from a wooden trough]] |

[[File:AWM H15216 12th Light Horse at Beersheba 1917.jpg|right|thumb|Horses from the 12th Light Horse Regiment drink at Beersheba |alt=A line of horses drink from a wooden trough]] |

||

Revision as of 09:19, 21 September 2013

| 12th Light Horse Regiment | |

|---|---|

| File:12thALHRbadge.jpg 12th Australian Light Horse Regiment hat badge | |

| Active | 1915–1919 1921–1936 1938–1943 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Australian Army |

| Type | Light Horse |

| Role | Mounted Infantry |

| Size | ~ 500 men |

| Part of | 4th Light Horse Brigade |

| Engagements | First World War |

| Insignia | |

| Unit Colour Patch |  |

The 12th Light Horse Regiment was a light horse regiment of the Australian Army. It was originally raised in 1915 as part of the Australian Imperial Force for service during the First World War. After fighting at Gallipoli as reinforcements, the regiment served in the Sinai and Palestine campaign against the Ottoman Empire before being disbanded after the war in late 1919. In 1921, the regiment was re-raised as a part-time unit of the Citizens Force based in New South Wales, before being amalgamated with the 24th Light Horse Regiment in 1936. In 1938, the regiment was reformed and during the Second World War it undertook garrison duties in Australia after being converted first to a motor regiment and then later to an armoured car regiment. It was disbanded in 1944 without having seen active service and was never re-raised. Today, its honours and traditions are held by the 12th/16th Hunter River Lancers.

History

Formation and training

The regiment was established on 1 March 1915[Note 1] at Liverpool, New South Wales, and two days later began forming at Holsworthy as part of the all-volunteer Australian Imperial Force (AIF), which was raised for service overseas during the First World War. Drawing the majority of its personnel from outback New South Wales, the regiment was assigned to the newly formed 4th Light Horse Brigade along with the 11th and 13th Light Horse Regiments and was placed under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Percy Abbott.[3] Upon establishment, the regiment had an authorised strength of 25 officers and 497 other ranks, who were organised into a regimental headquarters and three squadrons, each of which consisted of six troops.[4] Although mounted on horses, the Australian light horse regiments were not set up to undertake cavalry operations and were in fact considered to be mounted infantry. Armed with standard infantry weapons instead of swords or lances,[5] they were to ride into battle, using their Australian Waler horses[6] to obtain the mobility that foot soldiers did not possess.[5]

Following this, the regiment undertook basic training which included weapons handling, ceremonial drill, mounted and dismounted tactics and regimental manoeuvres. In late April, they marched through the centre of Sydney as part of a farewell before deploying overseas. On 9 June, the units of the 4th Light Horse Brigade began to concentrate and two days later the majority of the regiment embarked upon the troopship SS Suevic.[7] After four days steaming, the regiment received orders to put into Adelaide, South Australia, where they disembarked their horses due to concerns about death rates among horses travelling at that time of year. The men continued on their journey three days later, undertaking rifle and signals training on deck during the day. They crossed the equator in the early afternoon on 5 July; a short time later an epidemic of measles broke out amongst the men of the regiment.[8]

On 11 July, the 4th Light Horse Brigade received orders to interrupt its journey to Egypt and instead disembark at Aden, where there were concerns about an Ottoman attack. They were briefly put ashore during this time and conducted a reconnaissance to the frontier, before undertaking a 6-mile (9.7 km) route march. Nevertheless, the expected attack did not come and on 18 June the regiment continued on its way, arriving at Suez on 23 June. Following this they moved into a camp at Heliopolis, near Cairo,[9] and after receiving a small number of reinforcements and replacement horses, they began a period of intense training and guard duties as they acclimatised to the local conditions.[10]

Gallipoli

Elsewhere, the Gallipoli campaign had developed into a bloody stalemate. The regiments of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Light Horse Brigades had already been sent to the peninsula as reinforcements, however, the failed August Offensive had resulted in heavy casualties for the Australians and further reinforcements were required. As a result, the regiments of the 4th Light Horse Brigade were broken up to make up the losses in the other brigades.[11] The troops were not initially informed of this, however, and following the train trip to Alexandria on 25 August they embarked upon the SS Marquette and sailed to Lemnos Island where they were transferred to the Prince Abbas. Early on the morning 29 August, the regiment went ashore at Anzac Cove upon lighters;[12] later that afternoon they received the news that they were to be broken up among the other New South Wales light horse regiments that were already ashore.[13] The Machine-Gun Section and 'A' Squadron were sent to the 1st Light Horse Regiment around Walker's Ridge, becoming that regiment's 'B' Squadron; 'B' Squadron went to the 7th Light Horse Regiment at Ryrie's Post, adopting the designation of 'D' Squadron; 'C' Squadron went to the 6th Light Horse Regiment around Holly Spur and Lone Pine, becoming their 'D' Squadron; and the Regimental Headquarters was absorbed by the headquarters of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, while Abbott took command of the 10th Light Horse Regiment.[14]

For the remainder of the campaign, about 600 men from the regiment – including a batch of reinforcements that arrived in early October – carried out mainly defensive duties before leaving with the last Australian troops to be evacuated from the peninsula on 20 December.[15] They did not take part in any large-scale battles, but were involved in fighting off a number of sharp attacks. The exact number of casualties suffered is not known, but 18 men from the regiment are known to have been killed in this time.[16]

Sinai

Following their evacuation from Gallipoli, it was a number of weeks before the regiment was reformed. This occurred on 22 February 1916,[17] when all three squadrons assembled at Heliopolis. Under a new commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel John Royston, who was a veteran of the Boer War and who had replaced Abbott after he had been sent to England, the regiment began to reform.[18] Although other units, specifically part of the 4th and all of the 13th Light Horse Regiment, were sent to France where they were to take part in the fighting along the Western Front,[11] the 12th were destined to remain in the Middle East, where they would take part in the Sinai and Palestine campaign. Initially, the regiment would not be brigaded and would serve as a detached unit.[17][11]

After conducting infantry training in early April around Tel-el-Kebir, the regiment was sent across the Suez Canal along a new railway that was being constructed through the Sinai towards Palestine. Here it was established around Kantara and a position known as "Hill 70".[18] The following month, Ottoman forces began clashing with positions around the railhead and on 14 May, after a British garrison was attacked at Dueidar, which was about 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) away from the regiment's positions at Hill 70. Tasked with relieving the troops from the Royal Scots Fusiliers, two squadrons were dispatched. Delayed by a navigational error, the regiment arrived in some disorder. After this they began work on constructing defences, while one squadron was detached to garrison Kasr-el-Nil; in early July they were sent on to Moascar.[19]

Later that month, the 12th were relieved at Dueidar and were sent back to Heliopolis. While there they received a new commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Harold McIntosh, who replaced Royston upon his elevation to serve as temporary commander of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade.[19] On 27 July the regiment, without its machine-gun section which had been detached to the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, was sent to Gebel Habeita to relieve the 9th Light Horse Regiment. After undertaking the first part of the journey to Seraphum by train, they marched the rest of the way.[19] In early August, Ottoman forces launched an attack on the British Empire forces at Romani. During this fighting, the 12th Light Horse Regiment was not directly engaged, except for its machine-gun section, although it was employed to provide flank protection carrying out patrols.[20]

In early September, the regiment moved to Bayoud. Later, it was attached to a British column along with the 11th Light Horse Regiment as well as an artillery battery and a regiment from the City of London Yeomanry.[21] Together, under the command of Major General A.G. Dallas,[22] they carried out a raid on an Ottoman position 60 kilometres (37 mi) away in the Maghara Hills. The operation took six days to complete and upon arrival, after discovering that the Ottoman force was greater than expected, Dallas decided to limit his objectives to mounting a "demonstration" rather than a full attack. Within this plan, the 12th were allocated the task of advancing on the right flank during the attack. They proceeded to advance across the open ground on their horses, before dismounting to ascend towards the position. As the Ottoman fire increased, the 12th provided covering fire with machine-guns and rifles while the 11th came forward using their bayonets to clear the Ottomans from the forward position. At this point, instead of committing the light horsemen to a further assault on the main position, Dallas gave the order to withdraw, as they had achieved their purpose.[23][24]

Following this, the 12th were sent back to the rear to rest, arriving at the railhead at El Ferdan on the Suez in late October. 'A' Squadron established itself there, while 'B' and 'C' Squadrons along with the Machine-Gun Section were sent on to Ferry Post. There they undertook frequent patrols, with 'A' Squadron permanently detaching a troop to Badar Mahadat.[25]

Palestine

In early 1917, the regiment's time of operating as a detached unit came to an end,[17] when the 4th Light Horse Brigade was reconstituted at Ferry Post on 13 February under the command of Brigadier General John Meredith; assigned along with the 12th at this time were the 4th and 11th Light Horse Regiments.[26][27] For the next month they undertook training exercises before joining the advance into Palestine.[17] It was around this time, a number of men from the regiment were detached to join Dunsterforce.[26] In April, the regiment took part in the Second Battle of Gaza, during which it suffered heavy casualties – over 30 percent – including their commanding officer, McIntosh, who was gravely wounded.[28] He subsequently died of his wounds and was replaced by the second-in-command, Major Donald Cameron, who was later promoted to lieutenant colonel.[29][30] Assigned the task of attacking the Atawineh Redoubt early in the morning of 19 April, the regiment had dismounted about 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) from it and advanced on foot. Initially they made good progress and were able to capture a ridge about 1.8 kilometres (1.1 mi) from their objective without even firing a shot. At this point, though, the defensive fire grew more intense, forcing the men to take to the ground and begin fire and movement drills. Spread thinly across a 900-metre (980 yd) front with just 500 men,[31] they were dangerously exposed as machine-gun fire began to take its toll, checking the Australians' advance. Nevertheless they held their positions throughout the day until being withdrawn to a nearby hill that night, by which time they had suffered more than 30 percent casualties.[29]

The following day the 12th Light Horse Regiment established their position, digging-in and undertaking patrols as part of preparations to resist a possible Ottoman counterattack. Although they were harassed throughout the day with sniper fire, the attack never came.[29] They remained in their positions until three days later when they were withdrawn back to Shaquth, where they improved the defences and conducting patrols for the next fortnight before dispatching two squadrons in early May to attack an Ottoman foraging party at Esani.[32] The attack proved unsuccessful, however, as the Australians' approach was spotted, allowing the Ottomans and their Bedouin workers to withdraw before they could be engaged.[32]

The regiment's next major action did not come until October 1917 when it took part in the fighting around Beersheba,[17] which was conceived as part of a third attempt to capture Gaza. During this battle, along with the 4th Light Horse Regiment, the 12th carried out a famously successful mounted charge, advancing over open ground late in the afternoon to get under the Ottoman guns and capture the town and its vital water supplies.[33][34] Late in the afternoon, advancing on the left of the 4th, the 12th Light Horse Regiment advanced on a "squadron frontage in three lines" from 300–500 yards (270–460 m) and together they launched a "pure cavalry" charge with the soldiers advancing with bayonets in their hands.[35] Advancing over 6,000 metres (6,600 yd),[36] the light horsemen were subjected to rifle and machine-gun fire and artillery bombardment from the flanks and trenches to their front. Supporting artillery helped suppress the machine-gun fire from the flanks,[37] and the speed of the charge made it difficult for the Ottoman gunners to adjust their range. The Ottoman trenches were not protected with wire and after jumping over the trenches, the light horsemen dismounted and hand-to-hand fighting followed.[38] The battle was a stunning success with over 700 Ottoman soldiers captured and, more significantly for the Australians, over 400,000 litres of water secured. But it came at a price for the 12th who lost 24 men killed and 15 wounded;[39][40] the regiment also lost 44 horses killed in action, while another 60 were wounded or became sick.[41]

The success at Beersheeba significantly reduced Ottoman resistance and steadily they began to fall back with the British Empire troops following them in pursuit.[17] The regiment remained at Beersheeba for four days where they received remounts, and then throughout November the regiment advanced further into Palestine as part of the plan to capture Jerusalem. Advancing towards Khurbet Buteihah, the regiment took part in an engagement around Sheria on 7 November, but was forced to call a halt to their charge as their horses needed water, and amidst artillery and machine-gun fire, the regiment dismounted.[42][43] The following day, the 12th was sent to Beit Hanun to contact the Imperial Service Cavalry brigade, before searching for water around Sin Sin and Faluje, where they captured a number of Ottoman troops before rejoining the Australian Mounted Division at Huj. On 10 November, the 12th provided support to the 11th Light Horse Regiment when they came under attack at Hill 248 by a strong Ottoman counterattack, which was turned back.[44] After moving on to Summeil, they entered Et Tine on 14 November without firing a shot, securing a water source and a large amount of supplies, although a large amount of equipment was lost to a fire which had been set by the withdrawing garrison.[45] The 12th then took up an observation position at El Dhenebbe to support the British flank before moving to Wadi Menakh on 18 November to water their horses. They were then ordered to launch an attack around Abu Shushen, but were recalled before it began and amidst heavy rain camped at Deiran. Three days later, the 12th encamped at Mejdel for a week of rest along with the majority of its division.[46] After a brief respite, as the 4th Light Horse Brigade was sent to El Burj to relieve British forces there, the 12th went in to reserve; the horses were sent back to Deiran, and dismounted patrols and reconnaissance parties were sent out.[47]

In early December, they relieved the Scots Fusiliers in the Judean Hills to the north of the city. Supported by artillery, the 12th met no resistance and on 6 December it was able to establish itself along a line between Khed–Daty–Kureisnneh, manning a position about 800 metres (870 yd) from Ottoman positions. Initially it had only been planned for the unit to stay there for one night and as a result most of the cold weather equipment had been left behind. Nevertheless, the stay was extended and as winter came to Judea, heavy rain set in and the temperature dropped. Lacking cold weather equipment, redoubts were established along the front for shelter, while the men also took to caves in the hills.[48] On 11 December, the 4th Light Horse Brigade, having been relieved by the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, was withdrawn back to Kh Ed Daty, where they were employed as the Australian Mounted Division's reserve formation. On 28 December they advanced to a line between Jurdeh–Kuddis&Nalin to hold ground that had been captured as part of the advance on Jerusalem. At this time, the 12th established itself at Kuddis.[49]

In early in January 1918, the regiment received orders to move to Belah, which was situated near Gaza on the coast. For the next three months they remained there undertaking training.[49] In March, the 4th Light Horse Brigade, commanded by William Grant, was inspected by the Duke of Connaught, who likened the "snap and automatic precision" of their ceremonial drill to "a battalion of Grenadiers".[50] The following month they moved to Selmeh, near Jaffa, to assist the 74th Division's attack towards Haifa. The attack was called off, though, due to heavy resistance and the regiment was instead sent to the Jordan Valley, taking up positions near Jericho.[50]

Jordan and Syria

In late April 1918, the regiment was involved in a raid on Es Salt.[17][51] The raid was undertaken as part of a plan to capture the village in order to use it as a staging point for a further advance towards the railway junction at Deraa.[52] The regiment's role in the raid was to advance up the eastern side of the Jordan River to capture a river crossing 19 miles (31 km) to the north of Es Salt at Jisr ed Damieh in order to stop Ottoman reinforcements being sent to Es Salt from Nablus.[53] Initially the operation met with success, and although two of the 12th's squadrons had met strong resistance and been stopped at the bridge on the Es Salt track,[54] the village was secured by dusk on 30 April by troops of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade. Throughout the night, the 4th Light Horse Brigade assumed defensive positions; the 12th in the centre with the 4th on their left and the 11th on their right.[55] The following day, they were confronted by a force of around 4,000 Ottoman infantry along the Es Salt track, while another force of 1,000 infantry and 500 cavalry were further south, ready to force a second crossing.[55][56] After coming under attack, and finding themselves hard pressed, the 4th Light Horse Brigade was forced back to the south,[57] thereby exposing the rear of the troops holding Es Salt. Over the course of next few days little progress was made by the British Empire troops and, although the arrival of reinforcements helped steady the situation, the commander of the operation, Lieutenant General Harry Chauvel, decided that it was necessary to withdraw from the position on 3 May.[53] By 5 May the regiment had crossed the Jordan and had returned to its previous positions around Jericho.[58]

Throughout May the regiment was involved in construction of defences around Musallabeh, during which time the men suffered in the heat, which was at times as high as 50 °C (122 °F).[59] In addition to the heat, flies, scorpions, spiders and snakes infested their camp,[59] Many men from the 12th became sick with malaria and other conditions, before they were moved to Solomon's Pools, where the climate was more bearable.[60] In late June the regiment manned defences in the Jordan Valley before being sent to a camp amongst the olive groves at Ludd in early August.[61] While there, the regiment received cavalry training and was issued swords.[62]

The regiment departed Ludd on 18 September, taking up camp near Jaffa. Before dawn the next morning the regiment led the Australian Mounted Division's advance towards Semakh and Tiberias, moving by day to a position near Nahr Iskanderuneh where they rested until midnight. Pushing off again, the 12th trotted on to Liktera, 60 kilometres (37 mi) behind the original Ottoman front line.[63] There the regiment rested again until midday before making for Keikur Beidas; encountering a number of surrendering Ottoman troops along the way, it arrived there in the afternoon but halted only briefly before continuing on to the mouth of the Plain of Esdraelon, where they bivouacked for the night. The next morning the regiment proceeded to Jenin, where the 3rd Light Horse Brigade was in need of assistance guarding about 9,000 Ottoman prisoners. They also sent out patrols to the outlying villages and hills and established signal stations.[64]

On 22 September, following the 4th Light Horse Brigade's relief by the 5th Light Horse Brigade, the regiment was tasked with escorting 5,000 prisoners to El Lejjun before moving to Jisr ed Mejamie, along the Jordan River near its confluence with the Sea of Galilee at Lake Tiberias.[64] From there, in the early hours of 25 September, the 12th Light Horse Regiment, along with the rest of the brigade and one regiment from the 5th Light Horse Brigade, departed to conduct an attack on Semakh before rejoining the division's advance to Tiberias.[65] It was just before dawn and still dark when the advancing Australians came under heavy rifle and machine-gun fire from German and Ottoman positions near the railway station about 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) away.[66]

In response, the 11th Light Horse Regiment conducted a mounted charge which was checked just short of the objective, while one squadron from the 12th advanced along the left flank on horseback, and the other squadrons attempted to draw fire. Once close enough, the squadron from the 12th dismounted and put in a bayonet assault, which forced most of the defenders through the village, leaving the Germans defending the fortified railway station house by themselves.[65] At this point, under a white flag of truce, the Germans manning the station lured several Australians into a trap and killed them as they advanced to take the surrender. The result of this was that almost no quarter was shown as the Australians cleared the building, and later they refused to bury the German dead, which amounted to 98,[67] leaving their bodies to be looted by villagers.[68] In the battle, the regiment lost one man killed and 10 wounded, which was light compared to the losses suffered by the horses, which amounted to 61 killed and 27 injured.[69]

Following this, the regiment moved to the western side of the Jordan River towards high ground. Mid-morning on 25 September they reached El Menarah where, in concert with a number of armoured cars, they launched an attack that resulted in the capture of 200 German and Ottoman troops and a large amount of stores.[70] During the afternoon, the regiment occupied the town as the defending garrison withdrew and then, finding their way unopposed, the regiment entered Tiberias the following day.[69] From there, on 27 September, they began the final advance to Damascus. On 30 September, near Kaukab, about 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) from their objective, the 12th, along with the 4th, mounted a final charge. Forming up on the right with the 4th on their left in "column of squadrons" the regiment attacked across a maize field towards a spur near the Jebel es Aswad, advancing on a position that was reportedly strongly held.[71] In the end, the defenders did not fire a shot and the Australians took the position without suffering a casualty, capturing 12 machine-guns and taking 22 prisoners.[72] Following this, the regiment spent the night south-west of the city and the following day, 1 October 1918, was one of the first Australian units to enter Damascus, sending patrols in ahead of the main advance. The regiment then undertook a period of guard duty before being withdrawn to its outskirts, suffering heavily from illness.[73] Shortly after this, on 30 October, while the regiment was moving towards Homs, the Armistice of Mudros came into effect, ending the fighting.[17]

Disbandment

Following the end of the war, the 12th Light Horse Regiment remained in the Middle East for a number of months, during which time, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Phillip Chambers,[74] they were used to help suppress the 1919 Egyptian Uprising before being repatriated back to Australia.[17] During the uprising the 12th carried out security operations to protect key infrastructure in the Ismailia area.[75] As the situation was resolved, the regiment began the process of handing back its stores and equipment. Most of their horses were passed over to the Australian Remount Depot at Moascar at this time.[76] They would later be put down due to "cost constraints and quarantine restrictions" and concerns that they might be mistreated if they were left behind.[77]

Mid-morning on 22 July they embarked upon the Morvada which set sail from Kantara later that day. Cruising via Colombo, in Ceylon, the regiment made landfall at Fremantle on 17 August 1919, where the men were granted a brief period of leave before they continued on to Sydney, arriving there via Adelaide and Melbourne, on 28 August.[78] The regiment was disbanded a short time thereafter.[17]

During the war, the regiment lost 67 men killed and 401 men wounded.[79][Note 2] Members of the regiment received the following decorations: three Distinguished Service Orders (DSOs) and one Bar; five Military Crosses with one Bar; nine Distinguished Conduct Medals with one Bar; 14 Military Medals and 17 Mentioned in Despatches.[17] One member of the regiment, Major Eric Hyman, was recommended to receive the Victoria Cross for his involvement in the fighting around Beersheba, but the award was never approved.[80] Instead, Hyman received a DSO.[81]

Inter war years and subsequent service

In 1921, the decision was made to perpetuate the honours and traditions of the AIF by reorganising the units of the Citizens Force to replicate the numerical designations of their related AIF units.[82] As a result of this decision, the 12th Light Horse Regiment was re-raised as the 12th Light Horse Regiment based in the New England region of New South Wales and headquartered at Armidale.[83] In the process of its reformation, the regiment drew on the lineage of the Citizens Forces 12th (New England) Light Horse, which had existed parallel to the AIF light horse regiment and had remained in Australia during the war. This regiment, through a complex series of reorganisations could trace its lineage to the 6th Australian Light Horse Regiment, which had been raised in 1903 and which itself perpetuated units which had contributed personnel to fight in South Africa during the Boer War.[84]

During this time, it was assigned to the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, along with the 15th and 16th Light Horse Regiments.[85] In 1927, when territorial designations were adopted,[86] the regiment became known as the "New England Light Horse". At the same time, the regiment adopted the motto of Virtutis Fortuna Comes.[84]

The regiment remained in existence until 1 October 1936 when it was merged with the 24th (Gwydir) Light Horse to form the 12th/24th Light Horse;[84][87] these two units were later delinked in 1938 as part of an expansion of the Militia (as the Citizens Forces had become) in response to increasing political tensions in Europe.[83][88] In March 1942, during the Second World War, the 12th Light Horse was converted to a motor regiment, known as the 12th Motor Regiment.[84][89] In turn that unit was converted to the 12th Armoured Car Regiment in September 1942, but in 1943 it began to be broken up as its personnel were sent to other units as reinforcements and it was finally disbanded on 19 October 1943 having only undertaken garrison duty within Australia.[84][90]

When Australia's part-time military force was re-raised in the guise of the Citizens Military Force in 1948,[91] the regiment was not re-raised in its own right, although an amalgamated unit known as the 12th/16th Hunter River Lancers was established. Through this unit the 12th Light Horse Regiment's honours and traditions are perpetuated today.[92]

Alliances

The 12th Light Horse Regiment held the following alliances:[84]

Battle honours

The 12th Light Horse received the following battle honours:

- South Africa 1899–1902;[Note 3][84]

- First World War: Gallipoli 1915, Suvla, Sari-Bair, Egypt 1915–1917, Rumani, Palestine 1917–1918, Gaza–Beersheba, El Mughar, Nebi Samwill, Jerusalem, Jordan (Es Salt), Megiddo, Sharon, Damascus.[17][Note 4]

Commanding officers

The following is a list of the 12th Light Horse Regiment's commanding officers from 1915 to 1919:

- Lieutenant Colonel Percy Abbott (1915);[Note 5][94]

- Lieutenant Colonel John Royston (1916);[Note 6]

- Lieutenant Colonel Harold McIntosh (1916–1917);

- Lieutenant Colonel Donald Cameron (1917–1919);

- Lieutenant Colonel Philip Chambers (1919).[17][96]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ A previous 12th Light Horse Regiment had been formed in Tasmania in 1903, although that unit is not a predecessor to the 12th Light Horse Regiment that was raised during the First World War. That unit subsequently contributed a squadron to the 3rd Light Horse Regiment during the war and was later re-raised as the 22nd Light Horse Regiment.[1][2]

- ^ These figures differ slightly from those provided by the Australian War Memorial, which lists: 53 killed and 401 wounded.[17]

- ^ Inherited through predecessor units, having been originally awarded in 1908 to the 8th Australian Light Horse Regiment (New England Light Horse).[84]

- ^ This list differs from that of Hollis who details the regiment's battle honours as: South Africa 1899–1900, Suvla, Sari Bair, Gallipoli 1915, Nebi, Samwill, Jerusalem, Jordan (Es Salt), Megiddo, Sharon, Damascus, Palestine 1917–1918.[93]

- ^ Following the end of the war, Abbott resumed command of the regiment after it was re-raised as a part-time Citizens Forces unit, remaining in command until 1929.[94]

- ^ Royston was a South African-born officer who had fought during the Siege of Ladysmith and later commanded the Western Australian Mounted Infantry during the Boer War. Later he served during the Zulu Rebellion before organising the Natal Light Horse upon the outbreak of the First World War. After commanding the 12th Light Horse, Royston attained the rank of brigadier general and commanded the 2nd Light Horse Brigade temporarily, before taking command of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade, leading them until October 1917 when he returned to South Africa.[95]

- Citations

- ^ "Tasmanian Light Horse". PG Technologies. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ Festberg 1972, p. 54.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 2.

- ^ a b Gullett 1941, p. 29.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 39.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 4.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 5.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Gullett 1941, p. 54.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 10–15.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 23.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "12th Light Horse Regiment". First World War, 1914–1918 units. Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ a b Hollis 2008, p. 26.

- ^ a b c Hollis 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 29.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 200

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Gullett 1941, pp. 201–202

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 33.

- ^ a b Hollis 2008, p. 34.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 255.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 38–39.

- ^ a b c Hollis 2008, p. 39.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 321

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 38.

- ^ a b Hollis 2008, p. 42.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Perry 2009, pp. 318–323.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 395

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 135.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 396.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 401.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 60.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 432.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 63

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 473

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 63–64

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 64.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Hollis 2008, p. 66.

- ^ a b Hollis 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 145.

- ^ a b Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 146.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 605

- ^ a b Hollis 2008, p. 71.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 615

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 619

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 73.

- ^ a b Perry 2009, p. 397.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 76.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 77.

- ^ Perry 2009, p. 399.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 78.

- ^ a b Hollis 2008, p. 79.

- ^ a b Hollis 2008, p. 80.

- ^ Perry 2009, pp. 435–436.

- ^ Perry 2009, p. 437.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Hollis 2008, p. 81.

- ^ Gullett 1941, p. 736

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 85

- ^ Gullett 1941, pp. 746–749.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 86–88

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 94.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 93.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 114.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 111.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 104.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. 100.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 125.

- ^ a b "12th/16th Hunter River Lancers". Australian Light Horse Association. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Festberg 1972, p. 47.

- ^ Palazzo 2001, p. 102.

- ^ Stanley, Peter. "Broken Lineage: The Australian Army's Heritage of Discontinuity" (PDF). A Century of Service. Army History Unit. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ^ Bou 2010, p. 245.

- ^ Keogh 1965, p. 49.

- ^ "12 Light Horse". Orders of Battle.com. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "12 Armoured Car Regiment". Orders of Battle.com. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 200.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. viii.

- ^ Hollis 2008, p. ii.

- ^ a b Hogan 1979, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Jones 1988, pp. 472–473.

- ^ Hollis 2008, pp. 183–188.

References

- Bou, Jean (2010). Light Horse: A History of Australia's Mounted Arm. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19708-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopedia of Australia's Battles (1st ed.). St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-611-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Festberg, Alfred (1972). The Lineage of the Australian Army. Melbourne, Victoria: Allara Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85887-024-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69791-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gullett, Henry (1941). The Australian Imperial Force in Sinai and Palestine, 1914–1918. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. Volume VII (10th ed.). Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. OCLC 220624545.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hogan, Terry (1979). "Abbott, Percy Phipps (1869–1940)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. Volume 7. Melbourne, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. pp. 2–3. Retrieved 3 July 2010.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hollis, Kenneth (2008). Thunder of the Hooves: A History of 12 Australian Light Horse Regiment 1915–1919. Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military History Publications. ISBN 978-0-9803796-5-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, Ian (1988). "Royston, John Robinson (1860–1942)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. Volume 11. Melbourne, Victoria: Melbourne University Press. pp. 472–473. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keogh, Eustace (1965). South West Pacific 1941–45. Melbourne, Victoria: Grayflower Publications. OCLC 7185705.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Palazzo, Albert (2001). The Australian Army: A History of its Organisation 1901–2001. South Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-551507-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Perry, Roland (2009). The Australian Light Horse. Sydney, New South Wales: Hachette Australia. ISBN 978-0-7336-2272-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)