Artificial cranial deformation: Difference between revisions

Filling in 1 references using Reflinks |

Thanos5150 (talk | contribs) Original Neandertal claims in error and revised in 1999, Neandertals show no sings of artificial cranial deformation. |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

Intentional head moulding producing extreme cranial deformations was once commonly practised in a number of cultures widely separated geographically and chronologically, and so was probably independently invented more than once. It still occurs today in a few places, like [[Vanuatu]]. |

Intentional head moulding producing extreme cranial deformations was once commonly practised in a number of cultures widely separated geographically and chronologically, and so was probably independently invented more than once. It still occurs today in a few places, like [[Vanuatu]]. |

||

Early examples of intentional human cranial deformation predate [[written history]] |

Early examples of intentional human cranial deformation are believed to predate [[written history]] dating back to 45,000 BC in [[Neanderthal]] skulls, and to the Proto-[[Neolithic]] ''[[Homo sapiens]]'' component ([[12th millennium BC]]) from [[Shanidar Cave]] in [[Iraq]].<ref>{{cite journal |last= Trinkaus |first= Erik |date=April 1982|title= Artificial Cranial Deformation in the in Shanidar 1 and 5 Neandertals|journal= Current Anthropology |volume= 23|issue= 2|pages= 198–199|id= |quote= |doi= 10.1086/202808|jstor= 2742361 }}</ref><ref>A. Agelarakis, "The Shanidar Cave Proto-Neolithic Human Population: Aspects of Demography and Paleopathology", '' Human Evolution'', volume 8, no. 4 (1993), pp. 235-253.</ref> and also among Neolithic peoples in Southwest Asia.<ref>Christopher Meiklejohn, [[Anagnostis Agelarakis]], Ralph Solecki, Philip Smith, Canada), Peter Akkerman , "On the Origins of Cranial Artificial Deformation in SW Asia", ''Paleorient'', Volume 18 (1992), pp. 83-97; K.O. Lorentz, Ubaid headshaping, in R.A. Carter and G. Philip, ''Beyond the Ubaid'' (2010), pp. 125-148.</ref>. The Neanderthal cranial remains were newly reconstructed in 1999 by the anthropology team of Chech, Grove, Thorne, and Trinkaus, however, in which they discovered the original reconstruction of the skull was in error resulting in the conclusion "we no longer consider that artificial cranial deformation can be inferred for the specimen" <ref>http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/paleo_0153-9345_1999_num_25_2_4692</ref>. |

||

The earliest written record of cranial deformation dates to 400 BC in [[Hippocrates]]' description of the [[Macrocephali]] or Long-heads, who were named for their practice of cranial modification.<ref>''Hippocrates upon Air, Water, and Situation: upon Epidemical Diseases'', trans. Francis Clifton (1734), pp. 22-23.</ref> |

The earliest written record of cranial deformation dates to 400 BC in [[Hippocrates]]' description of the [[Macrocephali]] or Long-heads, who were named for their practice of cranial modification.<ref>''Hippocrates upon Air, Water, and Situation: upon Epidemical Diseases'', trans. Francis Clifton (1734), pp. 22-23.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:11, 22 May 2014

Artificial cranial deformation, head flattening, or head binding is a form of body alteration in which the skull of a human being is intentionally deformed. It is done by distorting the normal growth of a child's skull by applying force. Flat shapes, elongated ones (produced by binding between two pieces of wood), rounded ones (binding in cloth) and conical ones are among those chosen. It is typically carried out on an infant, as the skull is most pliable at this time. In a typical case, headbinding begins approximately a month after birth and continues for about six months.

History

Intentional head moulding producing extreme cranial deformations was once commonly practised in a number of cultures widely separated geographically and chronologically, and so was probably independently invented more than once. It still occurs today in a few places, like Vanuatu.

Early examples of intentional human cranial deformation are believed to predate written history dating back to 45,000 BC in Neanderthal skulls, and to the Proto-Neolithic Homo sapiens component (12th millennium BC) from Shanidar Cave in Iraq.[1][2] and also among Neolithic peoples in Southwest Asia.[3]. The Neanderthal cranial remains were newly reconstructed in 1999 by the anthropology team of Chech, Grove, Thorne, and Trinkaus, however, in which they discovered the original reconstruction of the skull was in error resulting in the conclusion "we no longer consider that artificial cranial deformation can be inferred for the specimen" [4].

The earliest written record of cranial deformation dates to 400 BC in Hippocrates' description of the Macrocephali or Long-heads, who were named for their practice of cranial modification.[5]

In the Old World, Huns[6] and Alans[7] are also known to have practised similar cranial deformation. In Late Antiquity (AD 300-600), the East Germanic tribes who were ruled by the Huns, adopted this custom (Gepids, Ostrogoths, Heruli, Rugii and Burgundians). In western Germanic tribes, artificial skull deformations have rarely been found.[8]

In the Americas the Maya, Inca, and certain tribes of North American natives performed the custom. In North America the practice was especially known among the Chinookan tribes of the Northwest and the Choctaw of the Southeast. The Native American group known as the Flathead did not in fact practise head flattening, but were named as such in contrast to other Salishan people who used skull modification to make the head appear rounder. However, other tribes, including the Choctaw,[9] Chehalis, and Nooksack Indians, did practise head flattening by strapping the infant's head to a cradleboard. The Lucayan people of the Bahamas practised it.[10] The practice was also known among the Australian Aborigines.

Friedrich Ratzel in The History of Mankind[11] reported in 1896 that deformation of the skull, both by flattening it behind and elongating it towards the vertex, was found in isolated instances in Tahiti, Samoa, Hawaii, and the Paumotu group and occurring most frequently on Mallicollo in the New Hebrides (today Malakula, Vanuatu), where the skull was squeezed extraordinarily flat.

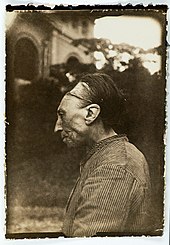

In the region of Toulouse (France), these cranial deformations persisted sporadically up until the early twentieth century;[12][13] however, rather than being intentionally produced as with some earlier European cultures, Toulousian Deformation seemed to have been the unwanted result of an ancient medical practice among the French peasantry known as bandeau, in which a baby's head was tightly wrapped and padded in order to protect it from impact and accident shortly after birth; in fact, many of the early modern observers of the deformation were recorded as pitying these peasant children, whom they believed to have been lowered in intelligence due to the persistence of old European customs. [14]

Methods and types

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2013) |

Deformation usually begins just after birth for the next couple of years until the desired shape has been reached or the child rejects the apparatus (Dingwall, 1931; Trinkaus, 1982; Anton and Weinstein, 1999).

There is no established classification system of cranial deformations. Many scientists have developed their own classification systems, but they have not agreed on a single classification for all forms that are seen (Hoshower et al., 1995).

In Europe and Asia, three main types of artificial cranial deformation have been defined by E.V. Zhirov (1941, p. 82):

- Round

- Fronto-occipital

- Sagittal.

Motivations

Cranial deformation was probably performed to signify group affiliation,[15] or to demonstrate social status. This may have played a key role in Maya society.[16] It could be aimed at creating a skull shape which is aesthetically more pleasing or associated with desirable attributes. For example, in the Nahai-speaking area of Tomman Island and the south south-western Malakulan (Australasia), a person with an elongated head is thought to be more intelligent, of higher status, and closer to the world of the spirits[citation needed]

Health effects

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2013) |

There is no statistically significant difference in cranial capacity between artificially deformed skulls and normal skulls in Peruvian samples.[17]

See also

References

- ^ Trinkaus, Erik (April 1982). "Artificial Cranial Deformation in the in Shanidar 1 and 5 Neandertals". Current Anthropology. 23 (2): 198–199. doi:10.1086/202808. JSTOR 2742361.

- ^ A. Agelarakis, "The Shanidar Cave Proto-Neolithic Human Population: Aspects of Demography and Paleopathology", Human Evolution, volume 8, no. 4 (1993), pp. 235-253.

- ^ Christopher Meiklejohn, Anagnostis Agelarakis, Ralph Solecki, Philip Smith, Canada), Peter Akkerman , "On the Origins of Cranial Artificial Deformation in SW Asia", Paleorient, Volume 18 (1992), pp. 83-97; K.O. Lorentz, Ubaid headshaping, in R.A. Carter and G. Philip, Beyond the Ubaid (2010), pp. 125-148.

- ^ http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/paleo_0153-9345_1999_num_25_2_4692

- ^ Hippocrates upon Air, Water, and Situation: upon Epidemical Diseases, trans. Francis Clifton (1734), pp. 22-23.

- ^ Facial reconstruction of a Hunnish woman, Das Historische Museum der Pfalz, Speyer

- ^ Bachrach, Bernard S., A history of the Alans in the West: from their first appearance in the sources of classical antiquity through the early Middle Ages, U of Minnesota Press (1973), pp. 67-69

- ^ Doris Pany and Karin Wiltschke-Schrotta, Artificial cranial deformation in a migration period burial of Schwarzenbach, Lower Austria, VIAVIAS, no. 2 (Vienna Institute for Archaeological Science 2008), pp. 18-23.

- ^ "Choctaw Indian History". Accessgenealogy.com. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ^ "Lucayan–Taíno burials from Preacher's cave, Eleuthera, Bahamas - Schaffer - 2010 - International Journal of Osteoarchaeology - Wiley Online Library". Onlinelibrary.wiley.com. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ^ Ratzel, Friedrich (1896). "The History of Mankind". MacMillan, London. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ Delaire MMJ, Billet J (1964) Considérations sur les déformations crâniennes intentionnelles. Rev Stomatol 69: 535–541

- ^ Janot, F, Strazielle, C, Awazu Pereira Da Silva, M, Cussenot, O (1993). Adaptation of facial architecture in the Toulouse deformity. Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy, 0930-1038, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01629867

- ^ "Chapter II : Later Artificial Cranial Deformation in Europe" (PDF). Bioanth.org. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

- ^ Gerszten and Gerszten, 1995; Hoshower et al., 1995; Tubbs, Salter, and Oaks, 2006.

- ^ Gerszten and Gerszten, 1995

- ^ "Exploring artificial cranial deformation using elliptic Fourier analysis of procrustes aligned outlines". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2003. p. 18. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help)

Bibliography

- Ellen FitzSimmons, Jack H. Prost, Sharon Peniston, "Infant Head Molding, A Cultural Practice", Arch Fam Med, Vol 7, Jan/Feb 1998

- Adebonojo, F. O., "Infant head shaping". JAMA, 1991;265:1179.

- Henshen F. The Human Skull: A Cultural History . New York, NY: Frederick A Praeger, 1966

External links

- A short discussion of cranial deformation[dead link]

- A Comparison of Images of Kushans from Coins and Sculpture

- Mathematical Analysis of Artificial Cranial Deformation

- Reconstruction of an Ostrogoth woman from a skull (intentionally deformed), discovered in Globasnitz (Carinthia, Austria) : [1], [2], [3], [4], [5].

- Elongated Skull Project