Life in Great Britain during the Industrial Revolution: Difference between revisions

→Child Labour: Good Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary Tags: Reverted Visual edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ |

{{Orphan|date=February 2009}} |

||

{{ |

{{Essay-like|article|date=January 2009}} |

||

{{essay-like|date=February 2019}}}} |

|||

'''Life in Great Britain during the Industrial Revolution''' shifted from an agrarian based society to an urban, industrialised society. New social and technological ideas were developed, such as the [[factory system]] and the [[steam engine]], in this time period. Work became more regimented, disciplined, and moved outside the home with large segments of the rural population migrating to the cities.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Society|first=National Geographic|date=2020-01-09|title=Industrial Revolution and Technology|url=http://www.nationalgeographic.org/article/industrial-revolution-and-technology/|access-date=2020-10-26|website=National Geographic Society|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

[[Industrial revolution]] is defined as the vast social and economic changes that resulted from the development of steam-powered machinery and mass-production methods, beginning in the late eighteenth century in Great Britain and extending through the nineteenth century elsewhere in the world. |

|||

The industrial belts of [[Great Britain]] included the [[Scottish Lowlands]], [[South Wales]], [[northern England]], and the [[English Midlands]]. The establishment of major factory centers assisted in the development of [[Canal|canals]], [[Road|roads]], and [[Rail transport|railroads]], particularly in [[Derbyshire]], [[Lancashire]], [[Cheshire]], [[Staffordshire]], [[Nottinghamshire]], and [[Yorkshire]].<ref>{{Cite web|last=Editors|first=History com|title=Industrial Revolution|url=https://www.history.com/topics/industrial-revolution/industrial-revolution|access-date=2021-04-04|website=HISTORY|language=en}}</ref> These regions saw the formation of a new workforce, described in [[Marxist theory]] as the ''[[proletariat]]''.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Constitutional Rights Foundation|url=https://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-19-2-a-karl-marx-a-failed-vision-of-history.html|access-date=2021-04-04|website=www.crf-usa.org}}</ref> |

|||

[[Industrial revolution]] brought unprecedented development in the lives of human beings. What are the impacts of industrial revolution on the lives of the British people during that time? Some of the basic questions that would be discussed are the impacts of industrialization on society and individuals from the technological changes in the agriculture, textile, railroad and mining industries. |

|||

== Living Standards == |

|||

The nature of the [[Industrial Revolution|Industrial Revolution's]] impact on living standards in Britain is debated among historians, with [[Charles Feinstein]] identifying detrimental impacts on British workers, whilst other historians, including Peter Lindert and [[Jeffrey G. Williamson|Jeffrey Williamson]] claim the [[Industrial Revolution]] improved the living standards of British people.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Nardinelli|first=Clark|title=Industrial Revolution and the Standard of Living|url=https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/IndustrialRevolutionandtheStandardofLiving.html|access-date=2020-11-06|website=The Library of Economics and Liberty|language=en}}</ref> Increasing employment of workers in factories led to a marked decrease in the working conditions of the average worker, as in the absence of [[Labour law|labour laws]], factories had few safety measures, and accidents resulting in injuries were commonplace.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Factories During The Industrial Revolution|url=https://industrialrevolution.org.uk/factories-industrial-revolution/|access-date=2020-11-06|website=Industrial Revolution|language=en}}</ref> Poor ventilation in workplaces such as [[Cotton mill|cotton mills]], [[Coal mine|coal mines]], [[Ironworks|iron-works]] and brick factories is thought to have led to development of [[Respiratory disease|respiratory diseases]] among workers.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Industrial Revolution: Definitions, Causes & Inventions - HISTORY|url=https://www.history.com/topics/industrial-revolution/industrial-revolution|access-date=2020-10-26|website=www.history.com}}</ref> |

|||

One can clearly observe the differences in life style in Britain before and after the industrial revolution. The industrial revolution brought fundamental changes in the livelihoods of people and in their standards of living. The central feature of industrialization – revolution in technology yielded a massive increase in per-capita productivity. Increased output could be used to improve material condition of the masses and sustain the population growth. It could also create inequalities among the standard of living by creating different classes of people. The factory owners aimed at making profits by maximizing their Return on Investment by maximizing the utilization of the machinery by making their workers work longer hours and by slashing wages. This created an upper middle class whose standard of living improved dramatically but the lives of the worker class changed very little or even became worse as they were exploited by the new factory owners. |

|||

Housing conditions of [[working class]] people who migrated to the cities was often overcrowded and unsanitary, creating a favourable environment for the spread of diseases such as [[Typhoid fever|typhoid]], [[cholera]] and [[smallpox]], further exacerbated by a lack of [[sick leave]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Standard of Living in Europe During the Industrial Revolution|url=https://foundations.uwgb.org/standard-of-living/|access-date=2020-11-06|website=Foundations of Western Culture|language=en}}</ref> There was however a rise in [[real income]] and increase in availability of various consumer goods to the lower classes during this period.<ref>Nardinelli</ref> Prior to the industrial revolution, increases in [[real wages]] would be offset by subsequent decreases, a phenomenon which ceased to occur following the revolution. The real wage of the average worker doubled in just 32 years from 1819 to 1851. which brought many people out of poverty.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lindert|first=Peter H.|first2=Williamson|last2=Jeffrey G.|date=1983|title=English Workers' Living Standards during the Industrial Revolution: A New Look|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2598895|journal=The Economic History Review|volume=36|issue=1|pages=1–25|doi=10.2307/2598895|issn=0013-0117}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== Britain leads the way== |

||

In the industrial districts, children tended to enter the workforce at younger ages than rural ones. Children were employed favourably over adults as they were deemed more compliant and therefore easier to deal with. Although most families channeled their children's earnings into providing a better diet for them, working in the factories tended to have an overall negative effect on the health of the children. Child labourers tended to be [[Orphan|orphans]], children of widows, or from the poorest families. |

|||

The pre-cursor for technological innovations to be created and adopted by the masses is the social, economical and political climate of the place along with the educational qualifications of the people. |

|||

Children were preferred workers in [[Textile manufacturing|textile mills]] because they worked for lower wages and had nimble fingers. Children's work mainly consisted of working under machines as well as cleaning and oiling tight areas. Children were physically punished by their superiors if they did not abide by their superiors expectations of work ethic. The punishments occurred as a result of the drive of master-manufacturers to maintain high output in the factories. The punishments and poor work conditions had a negative effect on the physical health of the children, causing physical deformities and illnesses. Furthermore, childhood diseases from this era have been linked to larger deformities in the future.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|last=Kirby|first=Peter|title=Child Workers and Industrial Health in Britain, 1780-1850|publisher=Boydell & Brewer|year=2014}}</ref> |

|||

Political and Socio-Economic situation - One of the major reasons why Britain was foremost in industrial revolution is that Britain had a stable political system and made technological progress in the late 1700s. Britain’s political system favored property owners. Well defined property rights are essential to promote innovation as a lot of money is invested in research. British patent law dates from the 1600’s. In some cases, the society itself rewarded innovators when the social benefits of the innovation are deemed to be much higher than the benefits from patents. |

|||

Gender was not a discriminator for how children were treated when working during the industrial revolution. Both boys and girls would start working at the age of four or five. A sizeable proportion of children working in the mines were under 13 and a larger proportion were aged 13-18. Mines of the era were not built for stability; rather, they were small and low. Children, therefore, were needed to crawl through them. The conditions in the mines were unsafe, children would often have limbs crippled, their bodies distorted, or be killed.<ref name=":0" /> Children could get lost within the mines for days at a time. The air in the mines was harmful to breathe and could cause painful and fatal diseases. |

|||

Transportation, Market Integration and favorable export policies – Britain had a good network of roads, canals and railroads which helped with the speedy transportation of raw materials and finished goods. Additional goods were exported to foreign countries as there were no restrictions on the same. |

|||

=== Reforms for change === |

|||

{{main article|Factory Acts}} |

|||

==Textile Industry== |

|||

The ''[[Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802]]'' tried to improve conditions for workers by making factory owners more responsible for the housing and clothing of the workers, but with little success. This act was never put into practice because magistrates failed to enforce it.<ref>{{Cite web|title=The 1802 Health and Morals of Apprentices Act|url=http://www.historyhome.co.uk/peel/factmine/1802act.htm|access-date=2020-10-27|website=www.historyhome.co.uk}}</ref> |

|||

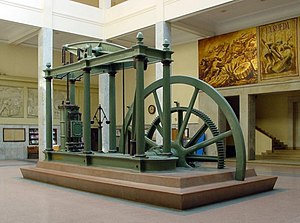

[[Image:Maquina vapor Watt ETSIIM.jpg|right|thumb|300px|A Watt steam engine.<ref>Watt steam engine image: located in the lobby of the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the UPM (Madrid)</ref>]] |

|||

The ''[[Cotton Mills and Factories Act 1819]]'' forbade the employment of children under the age of nine in [[cotton mill]]s, and limited the hours of work for children aged 9-16 to twelve hours a day. This act was a major step towards a better life for children since they were less likely to fall asleep during work, resulting in fewer injuries and beatings in the workplace.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Early factory legislation|url=https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/19thcentury/overview/earlyfactorylegislation/|access-date=2020-10-27|website=www.parliament.uk|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

One of the most impressive developments during the industrial revolution was the introduction of power-driven looms and spinning wheels in the textile industry which led the way for the early factories of Britain. |

|||

[[Michael Thomas Sadler|Michael Sadler]] was one of the pioneers in addressing the living and working conditions of industrial workers. In 1832, he led a parliamentary investigation of the conditions of textile workers. The Ashley Commission was another investigation committee, this time studying the situation of mine workers. One finding of the investigation was the observation alongside increased productivity, the number of working hours of the wage workers had also doubled in many cases.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Michael Thomas Sadler {{!}} British politician|url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Michael-Thomas-Sadler|access-date=2020-10-26|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The textile industry in Britain started as a home based industry in the late 1600’s. In the 1690’s the wool industry started as small ventures by farmers using family members to work the wool to provide supplemental income. Some of them started employing more workers to work for them and slowly became business owners. As more and more small businesses began expanding their operations by hiring wage workers during the early phases of the industrial revolution a new manufacturing middle class emerged. The mass production of goods resulted in cheaper products being available in larger quantities. The industrial revolution progressively replaced humans as the primary source of power for production with motors powered with steam. |

|||

The efforts of Michael Sadler and the Ashley Commission resulted in the passage of the [[Factory Acts#Althorp's Act (1833)|1833 act]] which limited the number of working hours for women and children. This bill limited children aged 9-18 to working no more than 48 hours a week, and stipulated that they spend two hours at school during work hours. The Act also created the [[factory inspector]] and provided for routine inspections of factories to ensure factories implemented the reforms.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Michael Thomas Sadler {{!}} British politician|url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Michael-Thomas-Sadler|access-date=2020-10-26|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

By the 1730s, cotton industry started picking up in Britain. In 1733, [[John Kay (flying shuttle)|John Kay]] invented the flying shuttle that was powered by the foot pedal, in 1733, by [[John Kay (flying shuttle)|John Kay]], an English artisan increased productivity by 100%. Resistance to the new technology by workers sensing this as a threat to their jobs delayed the widespread introduction.In 1764, [[James Hargreaves]] invented a spinning jenny device which drew out and twisted fibers into threads. In 1769, the first water powered spinning machine was invented by [[Richard Arkwright]]. The waterwheel demanded a constant supply of water and the factory had to be located near a river. He created accommodation for the factory workers as they had to be now relocated to be closer to their work locations. Samuel Slater left Great Britain to spreads ideas of industrialism in America. In 1770s and 1780s new bleaching and drying procedures were invented and roller printers for cloth designs. This replaced the intensive manual labor that involved block printing by hand. This increased productivity hundredfold at the same time reducing the skill levels of workers. With the invention and eventual adoption of the steam engine for powering looms by 1770, workers had to move into factories to do their work as opposed to their homes as the steam power could not be transmitted over long distances. This change forced people to abandon their homes and move closer to the factories. Increased productivity resulted in surplus goods available at lower prices. Export of goods became essential and cotton products were exported to Continental Europe, Latin America and Africa. |

|||

According to one cotton manufacturer: |

|||

==Transportation Industry== |

|||

{{Quote |

|||

|text=We have never worked more than seventy-one hours a week before Sir [[John Hobhouse, 1st Baron Broughton|John Hobhouse]]'s Act was passed. We then came down to sixty-nine; and since [[Lord Althorp]]'s Act was passed, in 1833, we have reduced the time of adults to sixty-seven and a half hours a week, and that of children under thirteen years of age to forty-eight hours in the week, though to do this latter has, I must admit, subjected us to much inconvenience, but the elder hands to more, in as much as the relief given to the child is in some measure imposed on the adult.<ref>{{cite web | title = The Life of the Industrial Worker in Ninteenth-Century<!--sic--> England | year = 2008 | access-date = 2008-04-28 | url=http://www.victorianweb.org/history/workers2.html}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

[[Image:Railroads_chart.gif|right|thumb|300px|Spread of Railways <ref> {{cite web | title = Modern History Sourcebook: Spread of Railways in 19th Century | year = 2008 | accessdate = 2008-04-28 | url=http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/indrev6.html }}</ref>]] |

|||

The first report for women and children in mines lead to the ''[[Mines and Collieries Act 1842]]'', which stated that children under the age of ten could not work in mines and that no women or girls could work in the mines. The second report in 1843 reinforced this act. |

|||

The most spectacular feature of industrialization in Britain occurred in the field of transportation. As productivity soared, ability to transport raw materials to the factories and finished products to market over long distances became a necessity. Improved roads and canals and rail transport were essential to sustain the growth. A major factor in Britain’s head start in technology in the early stages of Industrial Revolution is market integration – people and goods moved easily inside Britain. |

|||

The ''[[Factories Act 1847#Struggle in Parliament for the ten-hour day|Factories Act 1844]]'' limited women and young adults to working 12-hour days, and children from the ages 9 to 13 could only work nine-hour days. The Act also made mill masters and owners more accountable for injuries to workers. The ''[[Factories Act 1847]]'', also known as the ten-hour bill, made it law that women and young people worked not more than ten hours a day and a maximum of 63 hours a week. The last two major factory acts of the Industrial Revolution were introduced in 1850 and 1856. After these acts, factories could no longer dictate working hours for women and children. They were to work from 6 am to 6 pm in the summer, and 7 am to 7 pm in the winter. These acts took a lot of power and authority away from the manufacturers and allowed women and children to have more personal time for the family and for themselves. |

|||

Waterways were the cheapest and most effective mode to transport goods. Rivers were widened to make them more navigable and canals were built to connect cities with rivers. The first transatlantic steamship started carrying raw materials and finished goods by 1840’s. To improve road transportation, a series of turnpikes were built in the mid 1700’s. |

|||

The ''[[Prevention of Cruelty to, and Protection of, Children Act 1889]]'' aimed to stop the abuse of children in both the work and family sphere of life. |

|||

Advances in rail transportation had begun in the coal mines and the first steam engine for hauling coal was introduced in 1804.Reliable locomotives operating at speeds of 16 miles per hour became operational in 1827.Between 1820 and 1850 6000 miles of railways were opened and Britain entered the period of full industrialization. It’s economy was no longer dependent just on the textile sector but on capital goods production which moved it further along. |

|||

The ''[[Elementary Education Act 1870]]'' allowed all children within the United Kingdom to have access to education. Education was not made compulsory until 1880 since many factory owners feared the removal of children as a source of cheap labour. With the basic mathematics and English skills that children were acquiring, however, factory owners had a growing pool of workers who could read and |

|||

==Major Inventions== |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

* The first commercial Steam Engine was produced in 1698. It was patented by Thomas Slavery. |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

* In 1712 [[Thomas Newcomen]] improved on Savory’s Engine and it came into general use during the 1720’s. |

|||

* In 1733, [[John Kay (flying shuttle)|John Kay]] invented the flying shuttle-which increased the width of the cotton cloth and speed of a single weaver. |

|||

* In 1738, [[Lewis Paul]] and [[John Wyatt]] patented the roller spinning machine and the flyer-and bottom system. This allowed yarn to be spin quickly and efficiently. |

|||

* In 1764, The first cotton mill in the world was constructed in Lancashire, England. |

|||

* In 1771, [[Richard Arkwright]] invented the water frame. He used waterwheels to power looms that produced cotton cloth. |

|||

* In 1779, [[Samuel Crompton]] created the spinning wheel. His invention produced a stronger thread, and could be used in mass production. |

|||

* In 1785, [[James Watt]] improved New cowmen’s engine. His engine used heat more efficiently and less fuel. |

|||

* In 1803, [[William Radcliffe]] invented the dressing frame which allowed power looms to operate continuously. |

|||

* 1830-Nearly all basic tools for modern industry are in use. |

|||

==Impacts on the Society== |

|||

The industrial revolution was the driving force behind social change between the 18th and 19th centuries. It changed nearly all aspects of life through new inventions, new legislation, and spawned a new economy. |

|||

As a result of many new inventions such as the steam engine, locomotive and powered looms production and transportation of goods radically changed. With new mechanized machinery factories could be built and used to mass produce goods at a rate that human labor could never achieve. When the new factories were built they were often located in cities which lead to the migration of people from rural landscapes to an urban center. |

|||

The growth and expansion of the industrial revolution depended on being able to transport the goods that were produced. With the beginning of the revolution in Great Britain and the rest of Europe the amount of railways increased dramatically. As well as railways, more and more canals were being constructed because it was a cheaper alternative such as the Grand Trunk Canal built in 1777. |

|||

With an increase in goods the economy began to surge. The only way for the industrial revolution to continue expanding was through individual investors or financiers. This lead to the founding of banks to help regulate and handle the flow of money, and by 1800 London had around 70 banks. As the price of machinery and factories climbed the people who had the ability to provide capital became extremely important. |

|||

==Life of the workers during the Industrial Revolution== |

|||

The working conditions in the textile factories were substandard and the workers had to put in 70 hour weeks on a regular basis. The additional hours were supported with legislation. The manufacturers in the run to maximize productivity from the improvised machinery tried to extract more work from the over-stretched workers making their lives miserable. According to a cotton manufacturer, "We have never worked more than seventy-one hours a week before Sir JOHN HOBHOUSE'S Act was passed. We then came down to sixty-nine; and since Lord ALTHORP's Act was passed, in 1833, we have reduced the time of adults to sixty-seven and a half hours a week, and that of children under thirteen years of age to forty-eight hours in the week, though to do this latter has, I must admit, subjected us to much inconvenience, but the elder hands to more, inasmuch as the relief given to the child is in some measure imposed on the adult."<ref>{{cite web | title = The Life of the Industrial Worker in Ninteenth-Century<!--sic--> England | year = 2008 | accessdate = 2008-04-28 | url=http://www.victorianweb.org/history/workers2.html}}</ref> |

|||

Michael Sadler and was one of the pioneers in addressing the living and working conditions of the industrial workers. In 1832, he led a parliamentary investigation of the conditions of the textile workers. Ashley Commission was another investigation committee that studied the plight of the mine workers. The excerpts below from the interviews with witnesses bring out the life of the industrial class during the middle of the industrial revolution when there was a great deal of technological innovation resulting in increased productivity. What came out of the investigation was that with increased productivity the number of working hours of the wage workers also doubled in most cases. The efforts of Michael Sadler and the Ashley Commission resulted in the passage of the 1833 act which limits the number of work hours for women and children. The Michael Sadler and the Ashley Commission invited people from different background as witnesses to examine the living conditions of the workers during that time. The committee report clearly tells us how miserable the situation was. An excerpt from Matthew Crabtree’s and Elizabeth Bentley’s testimony with the committee is quoted below. |

|||

'''Mr. Matthew Crabtree''' |

|||

:What age are you? — Twenty-two. |

|||

:What is your occupation? — A blanket manufacturer. |

|||

:Have you ever been employed in a factory? — Yes. |

|||

:At what age did you first go to work in one? — Eight. |

|||

:How long did you continue in that occupation? — Four years. |

|||

:Will you state the hours of labor at the period when you first went to the factory, in ordinary times? — From 6 in the morning to 8 at night. |

|||

:Fourteen hours? — Yes. |

|||

:With what intervals for refreshment and rest? — An hour at noon. |

|||

:When trade was brisk what were your hours? — From 5 in the morning to 9 in the evening. |

|||

:Sixteen hours? — Yes. |

|||

:With what intervals at dinner? — An hour. |

|||

:How far did you live from the mill? — About two miles. |

|||

'''Elizabeth Bentley''' |

|||

:What age are you? — Twenty-three. Where do you live? — At Leeds. |

|||

:What time did you begin to work at a factory? — When I was six years old. |

|||

:At whose factory did you work? — Mr. Busk's. |

|||

:What kind of mill is it? — Flax-mill. |

|||

:What was your business in that mill? — I was a little doffer. |

|||

:What were your hours of labour in that mill? — From 5 in the morning till 9 at night, when they were thronged. |

|||

:For how long a time together have you worked that excessive length of time? — For about half a year. |

|||

:What were your usual hours when you were not so thronged? — From 6 in the morning till 7 at night. |

|||

:What time was allowed for your meals? — Forty minutes at noon. |

|||

:Had you any time to get your breakfast or drinking? — No, we got it as we could. |

|||

:And when your work was bad, you had hardly any time to eat it at all? — No; we were obliged to leave it or take it home, and when we did not take it, the overlooker took it, and gave it to his pigs. |

|||

:Do you consider doffing a laborious employment? — Yes. |

|||

:Any time allowed for you to get your breakfast in the mill? — No. |

|||

==Child Labor== |

|||

Child labor usually refers to a child who works to produce a good or service that can be sold for money whether they were paid or not. In pre-industrial Europe it was common for children to learn a skill or trade from their father, and open a business of their own in their mid twenties. During the industrial revolution, instead of learning a trade, children were paid menial wages to be the primary workers in textile mills and mines. Sending boys up chimneys to clean them was a common practice, and a dangerous and cruel one. Lord Ashley became the chief advocate of the use of chimney-sweeping machinery and of legislation to require its use. |

|||

During the industrial revolution, factories were criticized for long work hours, deplorable conditions, and low wages. Children as young as 5 and 6 could be forced to work a 12-16 hour day and earn as little as 4 shillings per week. Finally seeing a problem with child labor the British parliament passed three acts that helped regulate child labor |

|||

# Cotton Factories Regulation Act 1819<br /> |

|||

## Set the minimum working age to 9<br /> |

|||

## Set the maximum working hours to 12 per day<br /> |

|||

# Regulation of Child Labor Law 1833<br /> |

|||

## Established paid inspectors to inspect factories on child labor regulations and enforce the law<br /> |

|||

# [[Ten Hours Bill]] 1847<br /> |

|||

## Limited working hours to 10 per day for women and children |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist}} |

|||

* Clark, Gregory (2007) ''A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World'' Princeton University Press {{ISBN|978-0-691-12135-2}}. |

|||

===Primary sources=== |

|||

* [[Joel Mokyr|Mokyr, Joel]]. (1990). The Lever of Riches - Technological Creativity and Economic Progress. Oxford University Press. {{ISBN|0-19-506113-6}}. |

|||

# [[Joel Mokyr|Mokyr, Joel]]. ( 1990). The Lever of Riches - Technological Creativity and Economic Progress. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506113-6. This book documents the analysis and comparisons in technological progress between Britain and the rest of the world. |

|||

*Stearns, Peter N. (1993). The Industrial Revolution in World History. Westview Press. {{ISBN|0-8133-8596-2}}. |

|||

# Stearns, Peter N. ( 1993). The Industrial Revolution in World History. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8596-2. This book discusses the causes for industrial revolution and why it happened in eighteenth-century Britain. It documents the economic transformation in Britain during the Industrial Revolution. |

|||

== |

===Secondary Sources=== |

||

# [http://www.victorianweb.org/technology/ir/ir1.html The Industrial Revolution: An Introduction]. This site provides an introduction to the industrial revolution in Britain. |

|||

{{Wikivoyage|Industrial Britain}} |

|||

# [http://www.victorianweb.org/technology/ir/ir1.html The Industrial Revolution: An Introduction]. |

|||

# [http://www.victorianweb.org/technology/railways/railway4.html The Growth of Victorian Railways]. |

# [http://www.victorianweb.org/technology/railways/railway4.html The Growth of Victorian Railways]. |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Industrial Revolution]] |

||

pipiman |

|||

[[Category: Industrial Revolution|Great Britain]] |

|||

Revision as of 12:14, 20 June 2021

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (January 2009) |

Industrial revolution is defined as the vast social and economic changes that resulted from the development of steam-powered machinery and mass-production methods, beginning in the late eighteenth century in Great Britain and extending through the nineteenth century elsewhere in the world.

Industrial revolution brought unprecedented development in the lives of human beings. What are the impacts of industrial revolution on the lives of the British people during that time? Some of the basic questions that would be discussed are the impacts of industrialization on society and individuals from the technological changes in the agriculture, textile, railroad and mining industries.

One can clearly observe the differences in life style in Britain before and after the industrial revolution. The industrial revolution brought fundamental changes in the livelihoods of people and in their standards of living. The central feature of industrialization – revolution in technology yielded a massive increase in per-capita productivity. Increased output could be used to improve material condition of the masses and sustain the population growth. It could also create inequalities among the standard of living by creating different classes of people. The factory owners aimed at making profits by maximizing their Return on Investment by maximizing the utilization of the machinery by making their workers work longer hours and by slashing wages. This created an upper middle class whose standard of living improved dramatically but the lives of the worker class changed very little or even became worse as they were exploited by the new factory owners.

Britain leads the way

The pre-cursor for technological innovations to be created and adopted by the masses is the social, economical and political climate of the place along with the educational qualifications of the people.

Political and Socio-Economic situation - One of the major reasons why Britain was foremost in industrial revolution is that Britain had a stable political system and made technological progress in the late 1700s. Britain’s political system favored property owners. Well defined property rights are essential to promote innovation as a lot of money is invested in research. British patent law dates from the 1600’s. In some cases, the society itself rewarded innovators when the social benefits of the innovation are deemed to be much higher than the benefits from patents.

Transportation, Market Integration and favorable export policies – Britain had a good network of roads, canals and railroads which helped with the speedy transportation of raw materials and finished goods. Additional goods were exported to foreign countries as there were no restrictions on the same.

Textile Industry

One of the most impressive developments during the industrial revolution was the introduction of power-driven looms and spinning wheels in the textile industry which led the way for the early factories of Britain.

The textile industry in Britain started as a home based industry in the late 1600’s. In the 1690’s the wool industry started as small ventures by farmers using family members to work the wool to provide supplemental income. Some of them started employing more workers to work for them and slowly became business owners. As more and more small businesses began expanding their operations by hiring wage workers during the early phases of the industrial revolution a new manufacturing middle class emerged. The mass production of goods resulted in cheaper products being available in larger quantities. The industrial revolution progressively replaced humans as the primary source of power for production with motors powered with steam.

By the 1730s, cotton industry started picking up in Britain. In 1733, John Kay invented the flying shuttle that was powered by the foot pedal, in 1733, by John Kay, an English artisan increased productivity by 100%. Resistance to the new technology by workers sensing this as a threat to their jobs delayed the widespread introduction.In 1764, James Hargreaves invented a spinning jenny device which drew out and twisted fibers into threads. In 1769, the first water powered spinning machine was invented by Richard Arkwright. The waterwheel demanded a constant supply of water and the factory had to be located near a river. He created accommodation for the factory workers as they had to be now relocated to be closer to their work locations. Samuel Slater left Great Britain to spreads ideas of industrialism in America. In 1770s and 1780s new bleaching and drying procedures were invented and roller printers for cloth designs. This replaced the intensive manual labor that involved block printing by hand. This increased productivity hundredfold at the same time reducing the skill levels of workers. With the invention and eventual adoption of the steam engine for powering looms by 1770, workers had to move into factories to do their work as opposed to their homes as the steam power could not be transmitted over long distances. This change forced people to abandon their homes and move closer to the factories. Increased productivity resulted in surplus goods available at lower prices. Export of goods became essential and cotton products were exported to Continental Europe, Latin America and Africa.

Transportation Industry

The most spectacular feature of industrialization in Britain occurred in the field of transportation. As productivity soared, ability to transport raw materials to the factories and finished products to market over long distances became a necessity. Improved roads and canals and rail transport were essential to sustain the growth. A major factor in Britain’s head start in technology in the early stages of Industrial Revolution is market integration – people and goods moved easily inside Britain.

Waterways were the cheapest and most effective mode to transport goods. Rivers were widened to make them more navigable and canals were built to connect cities with rivers. The first transatlantic steamship started carrying raw materials and finished goods by 1840’s. To improve road transportation, a series of turnpikes were built in the mid 1700’s.

Advances in rail transportation had begun in the coal mines and the first steam engine for hauling coal was introduced in 1804.Reliable locomotives operating at speeds of 16 miles per hour became operational in 1827.Between 1820 and 1850 6000 miles of railways were opened and Britain entered the period of full industrialization. It’s economy was no longer dependent just on the textile sector but on capital goods production which moved it further along.

Major Inventions

- The first commercial Steam Engine was produced in 1698. It was patented by Thomas Slavery.

- In 1712 Thomas Newcomen improved on Savory’s Engine and it came into general use during the 1720’s.

- In 1733, John Kay invented the flying shuttle-which increased the width of the cotton cloth and speed of a single weaver.

- In 1738, Lewis Paul and John Wyatt patented the roller spinning machine and the flyer-and bottom system. This allowed yarn to be spin quickly and efficiently.

- In 1764, The first cotton mill in the world was constructed in Lancashire, England.

- In 1771, Richard Arkwright invented the water frame. He used waterwheels to power looms that produced cotton cloth.

- In 1779, Samuel Crompton created the spinning wheel. His invention produced a stronger thread, and could be used in mass production.

- In 1785, James Watt improved New cowmen’s engine. His engine used heat more efficiently and less fuel.

- In 1803, William Radcliffe invented the dressing frame which allowed power looms to operate continuously.

- 1830-Nearly all basic tools for modern industry are in use.

Impacts on the Society

The industrial revolution was the driving force behind social change between the 18th and 19th centuries. It changed nearly all aspects of life through new inventions, new legislation, and spawned a new economy.

As a result of many new inventions such as the steam engine, locomotive and powered looms production and transportation of goods radically changed. With new mechanized machinery factories could be built and used to mass produce goods at a rate that human labor could never achieve. When the new factories were built they were often located in cities which lead to the migration of people from rural landscapes to an urban center.

The growth and expansion of the industrial revolution depended on being able to transport the goods that were produced. With the beginning of the revolution in Great Britain and the rest of Europe the amount of railways increased dramatically. As well as railways, more and more canals were being constructed because it was a cheaper alternative such as the Grand Trunk Canal built in 1777.

With an increase in goods the economy began to surge. The only way for the industrial revolution to continue expanding was through individual investors or financiers. This lead to the founding of banks to help regulate and handle the flow of money, and by 1800 London had around 70 banks. As the price of machinery and factories climbed the people who had the ability to provide capital became extremely important.

Life of the workers during the Industrial Revolution

The working conditions in the textile factories were substandard and the workers had to put in 70 hour weeks on a regular basis. The additional hours were supported with legislation. The manufacturers in the run to maximize productivity from the improvised machinery tried to extract more work from the over-stretched workers making their lives miserable. According to a cotton manufacturer, "We have never worked more than seventy-one hours a week before Sir JOHN HOBHOUSE'S Act was passed. We then came down to sixty-nine; and since Lord ALTHORP's Act was passed, in 1833, we have reduced the time of adults to sixty-seven and a half hours a week, and that of children under thirteen years of age to forty-eight hours in the week, though to do this latter has, I must admit, subjected us to much inconvenience, but the elder hands to more, inasmuch as the relief given to the child is in some measure imposed on the adult."[3]

Michael Sadler and was one of the pioneers in addressing the living and working conditions of the industrial workers. In 1832, he led a parliamentary investigation of the conditions of the textile workers. Ashley Commission was another investigation committee that studied the plight of the mine workers. The excerpts below from the interviews with witnesses bring out the life of the industrial class during the middle of the industrial revolution when there was a great deal of technological innovation resulting in increased productivity. What came out of the investigation was that with increased productivity the number of working hours of the wage workers also doubled in most cases. The efforts of Michael Sadler and the Ashley Commission resulted in the passage of the 1833 act which limits the number of work hours for women and children. The Michael Sadler and the Ashley Commission invited people from different background as witnesses to examine the living conditions of the workers during that time. The committee report clearly tells us how miserable the situation was. An excerpt from Matthew Crabtree’s and Elizabeth Bentley’s testimony with the committee is quoted below.

Mr. Matthew Crabtree

- What age are you? — Twenty-two.

- What is your occupation? — A blanket manufacturer.

- Have you ever been employed in a factory? — Yes.

- At what age did you first go to work in one? — Eight.

- How long did you continue in that occupation? — Four years.

- Will you state the hours of labor at the period when you first went to the factory, in ordinary times? — From 6 in the morning to 8 at night.

- Fourteen hours? — Yes.

- With what intervals for refreshment and rest? — An hour at noon.

- When trade was brisk what were your hours? — From 5 in the morning to 9 in the evening.

- Sixteen hours? — Yes.

- With what intervals at dinner? — An hour.

- How far did you live from the mill? — About two miles.

Elizabeth Bentley

- What age are you? — Twenty-three. Where do you live? — At Leeds.

- What time did you begin to work at a factory? — When I was six years old.

- At whose factory did you work? — Mr. Busk's.

- What kind of mill is it? — Flax-mill.

- What was your business in that mill? — I was a little doffer.

- What were your hours of labour in that mill? — From 5 in the morning till 9 at night, when they were thronged.

- For how long a time together have you worked that excessive length of time? — For about half a year.

- What were your usual hours when you were not so thronged? — From 6 in the morning till 7 at night.

- What time was allowed for your meals? — Forty minutes at noon.

- Had you any time to get your breakfast or drinking? — No, we got it as we could.

- And when your work was bad, you had hardly any time to eat it at all? — No; we were obliged to leave it or take it home, and when we did not take it, the overlooker took it, and gave it to his pigs.

- Do you consider doffing a laborious employment? — Yes.

- Any time allowed for you to get your breakfast in the mill? — No.

Child Labor

Child labor usually refers to a child who works to produce a good or service that can be sold for money whether they were paid or not. In pre-industrial Europe it was common for children to learn a skill or trade from their father, and open a business of their own in their mid twenties. During the industrial revolution, instead of learning a trade, children were paid menial wages to be the primary workers in textile mills and mines. Sending boys up chimneys to clean them was a common practice, and a dangerous and cruel one. Lord Ashley became the chief advocate of the use of chimney-sweeping machinery and of legislation to require its use.

During the industrial revolution, factories were criticized for long work hours, deplorable conditions, and low wages. Children as young as 5 and 6 could be forced to work a 12-16 hour day and earn as little as 4 shillings per week. Finally seeing a problem with child labor the British parliament passed three acts that helped regulate child labor

- Cotton Factories Regulation Act 1819

- Set the minimum working age to 9

- Set the maximum working hours to 12 per day

- Set the minimum working age to 9

- Regulation of Child Labor Law 1833

- Established paid inspectors to inspect factories on child labor regulations and enforce the law

- Established paid inspectors to inspect factories on child labor regulations and enforce the law

- Ten Hours Bill 1847

- Limited working hours to 10 per day for women and children

References

- ^ Watt steam engine image: located in the lobby of the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the UPM (Madrid)

- ^ "Modern History Sourcebook: Spread of Railways in 19th Century". 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ "The Life of the Industrial Worker in Ninteenth-Century England". 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

Primary sources

- Mokyr, Joel. ( 1990). The Lever of Riches - Technological Creativity and Economic Progress. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506113-6. This book documents the analysis and comparisons in technological progress between Britain and the rest of the world.

- Stearns, Peter N. ( 1993). The Industrial Revolution in World History. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8596-2. This book discusses the causes for industrial revolution and why it happened in eighteenth-century Britain. It documents the economic transformation in Britain during the Industrial Revolution.

Secondary Sources

- The Industrial Revolution: An Introduction. This site provides an introduction to the industrial revolution in Britain.

- The Growth of Victorian Railways.

pipiman