Abortion in Mississippi: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Add: newspaper, pages, date, pmid, issue, title, authors 1-1. Changed bare reference to CS1/2. Removed parameters. Formatted dashes. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by BrownHairedGirl | Linked from User:BrownHairedGirl/Articles_with_new_bare_URL_refs | #UCB_webform_linked 169/3841 |

m Deleted unnecessary word "a" in sentence, " Free birth control correlates to teenage girls having a fewer pregnancies and fewer abortions." |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

== Context == |

== Context == |

||

{{See also|Abortion in the United States}}Free birth control correlates to teenage girls having |

{{See also|Abortion in the United States}}Free birth control correlates to teenage girls having fewer pregnancies and fewer abortions. A 2014 [[The New England Journal of Medicine|''New England Journal of Medicine'']] study found such a link. At the same time, a 2011 study by [[Center for Reproductive Rights]] and [[Ibis Reproductive Health]] also found that states with more abortion restrictions have higher rates of maternal death, higher rates of uninsured pregnant women, higher rates of infant and child deaths, higher rates of teen drug and alcohol abuse, and lower rates of cancer screening.<ref name=":03">{{Cite web|url=https://www.medicaldaily.com/states-more-abortion-restrictions-hurt-womens-health-increase-risk-maternal-death-306181|title=States With More Abortion Restrictions Hurt Women's Health, Increase Risk For Maternal Death|last=Castillo|first=Stephanie|date=2014-10-03|website=Medical Daily|access-date=2019-05-27}}</ref> The study singled out Oklahoma, Mississippi and Kansas as being the most restrictive states that year, followed by Arkansas and Indiana for second in terms of abortion restrictions, and Florida, Arizona and Alabama in third for most restrictive state abortion requirements.<ref name=":03" /> |

||

According to a 2017 report from the Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health, states that tried to pass additional constraints on a women's ability to access legal abortions had fewer policies supporting women's health, maternal health and children's health. These states also tended to resist expanding Medicaid, family leave, medical leave, and sex education in public schools.<ref name=":4">{{Cite web|url=https://www.nbcnews.com/health/womens-health/states-pushing-abortion-bans-have-higher-infant-mortality-rates-n1008481|title=States pushing abortion bans have highest infant mortality rates|website=NBC News|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref> In 2017, Georgia, Ohio, Missouri, Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi have among the highest rates of infant mortality in the United States.<ref name=":4" /> Mississippi had an infant mortality rate of 8.6 deaths per 1,000 live births.<ref name=":4" /> |

According to a 2017 report from the Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health, states that tried to pass additional constraints on a women's ability to access legal abortions had fewer policies supporting women's health, maternal health and children's health. These states also tended to resist expanding Medicaid, family leave, medical leave, and sex education in public schools.<ref name=":4">{{Cite web|url=https://www.nbcnews.com/health/womens-health/states-pushing-abortion-bans-have-higher-infant-mortality-rates-n1008481|title=States pushing abortion bans have highest infant mortality rates|website=NBC News|access-date=2019-05-25}}</ref> In 2017, Georgia, Ohio, Missouri, Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi have among the highest rates of infant mortality in the United States.<ref name=":4" /> Mississippi had an infant mortality rate of 8.6 deaths per 1,000 live births.<ref name=":4" /> |

||

Revision as of 00:39, 1 June 2022

This article may require copy editing for language use. "Fetal heartbeat" (or similar) is used incorrectly in Wikivoice; see Talk:Six-week abortion ban#Regarding the recent page change. (May 2022) |

Abortion in Mississippi is legal up to the 20th week of pregnancy.[citation needed] As of June 2021, a 59% majority of U.S. adults say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 39% think abortion should be illegal in all or most cases, a Pew Research Center survey finds.[1]

The number of abortion clinics have been declining in recent years, going from thirteen in 1982 to eight in 1992 to one since 2006 with that number remaining level as of 2019. There were 2,303 legal abortions in 2014, and 2,613 in 2015. Most women went out of state to get a legal abortion.

Terminology

The abortion debate most commonly relates to the "induced abortion" of an embryo or fetus at some point in a pregnancy, which is also how the term is used in a legal sense.[note 1] Some also use the term "elective abortion", which is used in relation to a claim to an unrestricted right of a woman to an abortion, whether or not she chooses to have one. The term elective abortion or voluntary abortion describes the interruption of pregnancy before viability at the request of the woman, but not for medical reasons.[2]

Anti-abortion advocates tend to use terms such as "unborn baby", "unborn child", or "pre-born child",[3][4] and see the medical terms "embryo", "zygote", and "fetus" as dehumanizing.[5][6] Both "pro-choice" and "pro-life" are examples of terms labeled as political framing: they are terms which purposely try to define their philosophies in the best possible light, while by definition attempting to describe their opposition in the worst possible light. "Pro-choice" implies that the alternative viewpoint is "anti-choice", while "pro-life" implies the alternative viewpoint is "pro-death" or "anti-life".[7] The Associated Press encourages journalists to use the terms "abortion rights" and "anti-abortion".[8]

Context

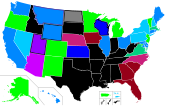

Free birth control correlates to teenage girls having fewer pregnancies and fewer abortions. A 2014 New England Journal of Medicine study found such a link. At the same time, a 2011 study by Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health also found that states with more abortion restrictions have higher rates of maternal death, higher rates of uninsured pregnant women, higher rates of infant and child deaths, higher rates of teen drug and alcohol abuse, and lower rates of cancer screening.[9] The study singled out Oklahoma, Mississippi and Kansas as being the most restrictive states that year, followed by Arkansas and Indiana for second in terms of abortion restrictions, and Florida, Arizona and Alabama in third for most restrictive state abortion requirements.[9]

According to a 2017 report from the Center for Reproductive Rights and Ibis Reproductive Health, states that tried to pass additional constraints on a women's ability to access legal abortions had fewer policies supporting women's health, maternal health and children's health. These states also tended to resist expanding Medicaid, family leave, medical leave, and sex education in public schools.[10] In 2017, Georgia, Ohio, Missouri, Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi have among the highest rates of infant mortality in the United States.[10] Mississippi had an infant mortality rate of 8.6 deaths per 1,000 live births.[10]

Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act was rejected by Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi and Missouri. Consequently, poor women in the typical age range to become mothers had a gap in coverage for prenatal care. According to Georgetown University Center for Children and Families research professor Adam Searing, "The uninsured rate for women of childbearing age is nearly twice as high in states that have not expanded Medicaid. [...] That means a lot more women who don't have health coverage before they get pregnant or after they have their children. [...] If states would expand Medicaid coverage, they would improve the health of mothers and babies and save lives."[10] According to the 2018 Premature Birth Report Cards, Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama were all given an F.[10] In the 2018 America's Health Rankings produced by United Health Foundation, Mississippi ranked 32nd in the country when it came to maternal mortality.[10] A 2018 March of Dimes report said the preterm birth rate among African American women in Mississippi was much higher, 44% higher, than women of all other races in the state.[10]

Poor women in the United States had problems paying for menstrual pads and tampons in 2018 and 2019. Almost two-thirds of poor women could not pay for them. These were not available through the federal Women, Infants, and Children Program (WIC).[11] Lack of menstrual supplies has an economic impact on poor women. A study in St. Louis found that 36% had to miss days of work because they lacked adequate menstrual hygiene supplies during their period. This was on top of the fact that many had other menstrual issues including bleeding, cramps and other menstrual induced health issues.[11] This state was one of a majority that taxed essential hygiene products like tampons and menstrual pads as of November 2018.[12][13][14][15]

History

In recent years, white women have played a major role in helping Republican male anti-abortion rights candidates get elected. In the 2018 U.S. Senate special election, around 84% of white women who voted chose Republican candidate Cindy Hyde-Smith, while 93% of black women who voted chose Democratic candidate Mike Espy.[16] One of the biggest groups of women who oppose legalized abortion in the United States are white southern evangelical Christians. These women voted overwhelming for Trump, with 80% of these voters supporting him at the ballot box in 2016. In November 2018, during US House exit polling, 75% of southern white evangelical Christian women indicated they supported Trump and only 20% said they voted for Democratic candidates.[16]

Legislative history

By the end of the 1800s, all states in the Union except Louisiana had therapeutic exceptions in their legislative bans on abortions.[17] In the 19th century, bans by state legislatures on abortion were about protecting the life of the mother given the number of deaths caused by abortions; state governments saw themselves as looking out for the lives of their citizens.[17]

In 1966, the Mississippi legislature made abortion legal in cases of rape.[18] By the end of 1972, Mississippi allowed abortion in cases of rape or incest only and Alabama and Massachusetts allowed abortions only in cases where the woman's physical health was endangered. In order to obtain abortions during this period, women would often travel from a state where abortion was illegal to states where it was legal.[19] Mississippi passed a parental consent law in the early 1990s. This law impacted when minors sought abortions, resulting in an increase of 19% for abortions sought after 12 weeks.[20][21]

On February 27, 2006, Mississippi's House Public Health Committee voted to approve a ban on abortion, but that bill died after the House and Senate failed to agree on compromise legislation.[22] The state was one of 23 states in 2007 to have a detailed abortion-specific informed consent requirement.[23] Mississippi, Nebraska, North Dakota and Ohio all had statutes in 2007 that required specific informed consent on abortion but also, by statute, allowed medical doctors performing abortions to disassociate themselves with the anti-abortion materials they were required to provide to their female patients.[24] By law, abortion providers in Alabama, Louisiana and Mississippi were required to perform ultrasounds before providing women with abortions, even in situations like in the first trimester where an ultrasound has no medical necessity.[24] Some states, such as Alaska, Mississippi, West Virginia, Texas, and Kansas, have passed laws requiring abortion providers to warn patients of a link between abortion and breast cancer, and to issue other scientifically unsupported warnings.[25][26][24] On November 8, 2011, the Personhood amendment, to define personhood as beginning "at the moment of fertilization, cloning, or the functional equivalent thereof," was rejected by 55 percent of voters.[27][28]

In 2013, state Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP) law applied to medication induced abortions and private doctor offices in addition to abortion clinics.[29] The state legislature was one of five states nationwide that tried, and failed, to pass a fetal heartbeat bill in 2013. Only North Dakota successfully passed such a law but it was later struck down by the courts.[28] In 2013, the state was one of five where the legislature introduced a bill that would have banned abortion in almost all cases. It did not pass. They tried and failed again in 2015, 2017 and 2018, where they were one of five, one of six, and one in eleven respectively.[30] The state legislature was one of four states nationwide that tried, and failed, to pass a fetal heartbeat bill in 2012.[28] In 2012, the Mississippi State Legislature passed a law that required abortion clinics to have doctors on staff with hospital admitting privileges. This almost led to the closure of the state's only abortion clinic.[31]

The state legislature was one of eight states nationwide that tried, and failed, to pass a fetal heartbeat bill in 2017.[28]

In March 2018, the Mississippi House passed House Bill 1510, the Gestational Age Act, that outlawed abortion after 15 weeks "except in a medical emergency or in the case of a severe fetal abnormality".[32][33] A difference between the Gestational Age Act and federal level bills which attempted to pass a Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act was that the Gestational Age Act does not allow exemptions in cases of rape or incest.[33][34] The state had a law on the books as of August 2018 that would be triggered if Roe v. Wade was overturned.[35]

Heartbeat bills in Mississippi died in committee in 2013,[36] 2014,[37][38] 2017,[39][40][41] 2018,[42][43][44][28] and 2019.[45]

Three more heartbeat bills were filed in the Mississippi Legislature in January 2019.[46] SB 2116, by Sen. Angela Burks Hill was referred to the Public Health and Welfare Committee on January 11, 2019.[47] HB 732, by Rep. Chris Brown was referred to the Public Health and Human Services Committee on January 17, 2019.[48] After passing out of their respective committees on February 5, 2019,[46] both SB 2116 and HB 732, were passed out of the Mississippi Senate and Mississippi House on February 13, 2019.[49] On March 19, 2019, the Senate concurred in the House amendments to SB 2116,[50] and on March 22, 2019, the fetal heartbeat bill was signed into law by Mississippi Governor Phil Bryant.[51]

In 2020, a law was enacted in Mississippi banning abortions based on the sex, race, or genetic abnormality of the fetus.[52]

Ballot box history

In the 2011 election season, Mississippi placed an amendment on the ballot that redefine how the state viewed abortion. The personhood amendment defined personhood as "every human being from the moment of fertilization, cloning or the functional equivalent thereof". If passed, it would have been illegal to get an abortion in the state.[53]

Judicial history

The US Supreme Court's decision in 1973's Roe v. Wade ruling meant the state could no longer regulate abortion in the first trimester.[17] On July 11, 2012, a Mississippi federal judge ordered an extension of his temporary order to allow the state's only abortion clinic to stay open. The order will stay in place until U.S. District Judge Daniel Porter Jordan III can review newly drafted rules on how the Mississippi Department of Health will administer a new abortion law. The law in question came into effect on July 1, 2012.[54]

On March 20, 2018, a federal district court in Mississippi enacted a temporary, 10-day ban of the enforcement of the Gestational Age Act due to its conflict with the established rights of the woman under Roe v. Wade.[55][56][57] The challenge to these decisions had been petitioned to the Supreme Court, which in May 2021 certified the petition, to be heard as Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization in the 2021–22 term.[58]

Clinic history

In the 1980s, there were around a dozen operating abortion clinics in the state.[31] Between 1982 and 1992, the number of abortion clinics in the state decreased by five, going from thirteen in 1982 to eight in 1992.[59] Since around 2006, Jackson Women's Health has been the only operating abortion clinic in Mississippi.[31] In 2010, the color of the building changed from beige to hot pink after the building was acquired by a new owner.[31]

In 2012, Jackson Women's Health almost closed as a result of a new state law being passed that required the clinic to have medical staff with hospital admitting privileges. None of the hospitals in Jackson wanted to give the qualified OB-GYNs on staff at the clinic those privileges. They were only saved at the last minute after a judge ruled in their favor.[31]

In 2014, there was still only one abortion clinic in Mississippi.[60] 99% of the counties in the state did not have an abortion clinic. That year, 91% of women in the state aged 15–44 lived in a county without an abortion clinic.[61] Around 90% of Jackson Women's Health services were abortion related in 2017. They saw around 30 to 40 patients per week.[31] In 2017, there was one Planned Parenthood clinic, which did not offer abortion services, in a state with a population of 694,045 women aged 15–49.[35] North Dakota, Wyoming, Mississippi, Louisiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia were the only six states as of July 21, 2017, not to have a Planned Parenthood clinic that offered abortion services.[35] In May 2019, the state was one of six states in the nation with only one abortion clinic.[62][63]

Statistics

In the period between 1972 and 1974, the state had an illegal abortion mortality rate per million women aged 15–44 of between 0.1 and 0.9.[64] In 1990, 289,000 women in the state faced the risk of an unintended pregnancy.[59] In 2010, the state had zero publicly funded abortions.[65] In 2014, 36% of adults said in a poll by the Pew Research Center that abortion should be legal in all or most cases.[66] 59% of people in Alabama said abortion should be "illegal in all or most cases."[67] According to a 2014 Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) study, 60% of white women, the same percentage as white men, in the state believed that abortion be illegal in all or most cases.[16] In 2017, medical and surgical abortions were split at around 50% each.[31]

| Census division and state | Number | Rate | % change 1992–1996 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | 1992 | 1995 | 1996 | ||

| Total | 1,528,930 | 1,363,690 | 1,365,730 | 25.9 | 22.9 | 22.9 | –12 |

| East South Central | 54,060 | 44,010 | 46,100 | 14.9 | 12 | 12.5 | –17 |

| Alabama | 17,450 | 14,580 | 15,150 | 18.2 | 15 | 15.6 | –15 |

| Kentucky | 10,000 | 7,770 | 8,470 | 11.4 | 8.8 | 9.6 | –16 |

| Mississippi | 7,550 | 3,420 | 4,490 | 12.4 | 5.5 | 7.2 | –42 |

| Tennessee | 19,060 | 18,240 | 17,990 | 16.2 | 15.2 | 14.8 | –8 |

| Location | Residence | Occurrence | % obtained by

out-of-state residents |

Year | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | No. | Rate^ | Ratio^^ | ||||

| Mississippi | 7,550 | 12.4 | 1992 | [68] | |||||

| Mississippi | 3,420 | 5.5 | 1995 | [68] | |||||

| Mississippi | 4,490 | 7.2 | 1996 | [68] | |||||

| Mississippi | 5,104 | 8.5 | 132 | 2,303 | 3.8 | 59 | 3.6 | 2014 | [69] |

| Mississippi | 4,699 | 7.8 | 122 | 2,613 | 4.4 | 68 | 5.1 | 2015 | [70] |

| Mississippi | 4,708 | 7.9 | 124 | 2,569 | 4.3 | 68 | 6.3 | 2016 | [71] |

| ^number of abortions per 1,000 women aged 15–44; ^^number of abortions per 1,000 live births | |||||||||

Women's abortion experiences

Mississippi local Laurie Bertram Roberts had an abortion after already having several children. During an ultrasound, she discovered that the fetus was not viable; she had two options: wait to miscarry or have an abortion. She said of reaching this point, "I realized then I'm not actually better or different. [...] I was sitting in the waiting room with all of these women who were just as scared as me. None of us looked like we wanted to be there. Some looked ready to get it over with. Life brought us to be at this spot, on this day, and it wasn't a value judgment."[62]

Abortion rights views and activities

Organizations

Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund assists women, primarily African American women, who need financial assistance to pay for an abortion by providing such assistance. It was founded by Laurie Bertram Roberts.[62]

Funding

After Mississippi passed abortion restrictions in 2019, Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund received a huge number of donations in the course of a single week totaling more than US$14,000.[72]

Protests

Women from the state participated in marches supporting abortion rights as part of a #StoptheBans movement in May 2019.[73]

Anti-abortion rights views and activities

Activities

During the 1980s and 1990s, anti-abortion rights activists would move around, protesting at different clinics around Jackson; they did not always protest at the same clinic on a day in and day out basis.[31]

In 2017, Jackson Women's Health had around 10 protesters outside their clinic on a daily basis.[31]

Violence

The Jackson Women's Health has been robbed several times. It also has had anti-abortion rights activists vandalize their cameras and their generator.[31]

Footnotes

- ^ According to the Supreme Court's decision in Roe v. Wade:

Likewise, Black's Law Dictionary defines abortion as "knowing destruction" or "intentional expulsion or removal".(a) For the stage prior to approximately the end of the first trimester, the abortion decision and its effectuation must be left to the medical judgement of the pregnant woman's attending physician. (b) For the stage subsequent to approximately the end of the first trimester, the State, in promoting its interest in the health of the mother, may, if it chooses, regulate the abortion procedure in ways that are reasonably related to maternal health. (c) For the stage subsequent to viability, the State in promoting its interest in the potentiality of human life may, if it chooses, regulate, and even proscribe, abortion except where it is necessary, in appropriate medical judgement, for the preservation of the life or health of the mother.

References

- ^ "About six-in-ten Americans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases".

- ^ Watson, Katie (20 Dec 2019). "Why We Should Stop Using the Term "Elective Abortion"". AMA Journal of Ethics. 20 (12): E1175-1180. doi:10.1001/amajethics.2018.1175. PMID 30585581. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Chamberlain, Pam; Hardisty, Jean (2007). "The Importance of the Political 'Framing' of Abortion". The Public Eye Magazine. 14 (1).

- ^ "The Roberts Court Takes on Abortion". New York Times. November 5, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2008.

- ^ Brennan 'Dehumanizing the vulnerable' 2000

- ^ Getek, Kathryn; Cunningham, Mark (February 1996). "A Sheep in Wolf's Clothing – Language and the Abortion Debate". Princeton Progressive Review.

- ^ "Example of "anti-life" terminology" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ Goldstein, Norm, ed. The Associated Press Stylebook. Philadelphia: Basic Books, 2007.

- ^ a b Castillo, Stephanie (2014-10-03). "States With More Abortion Restrictions Hurt Women's Health, Increase Risk For Maternal Death". Medical Daily. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g "States pushing abortion bans have highest infant mortality rates". NBC News. Retrieved 2019-05-25.

- ^ a b Mundell, E.J. (January 16, 2019). "Two-Thirds of Poor U.S. Women Can't Afford Menstrual Pads, Tampons: Study". US News & World Report. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- ^ Larimer, Sarah (January 8, 2016). "The 'tampon tax,' explained". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Bowerman, Mary (July 25, 2016). "The 'tampon tax' and what it means for you". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- ^ Hillin, Taryn. "These are the U.S. states that tax women for having periods". Splinter. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ^ "Election Results 2018: Nevada Ballot Questions 1-6". KNTV. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- ^ a b c Brownstein, Ronald (2019-05-23). "White Women Are Helping States Pass Abortion Restrictions". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- ^ a b c Buell, Samuel (1991-01-01). "Criminal Abortion Revisited". New York University Law Review. 66 (6): 1774–1831. PMID 11652642.

- ^ Tyler, C. W. (1983). "The public health implications of abortion". Annual Review of Public Health. 4: 223–258. doi:10.1146/annurev.pu.04.050183.001255. ISSN 0163-7525. PMID 6860439.

- ^ Kliff, Sarah (January 22, 2013). "CHARTS: How Roe v. Wade changed abortion rights". The Washington Post.

- ^ Adolescence, Committee On (2017-02-01). "The Adolescent's Right to Confidential Care When Considering Abortion". Pediatrics. 139 (2): e20163861. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-3861. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 28115537.

- ^ Henshaw, Stanley K. (May 1995). "The Impact of Requirements for Parental Consent on Minors' Abortions in Mississippi". Family Planning Perspectives. 27 (3): 120–122. doi:10.2307/2136110. ISSN 0014-7354. JSTOR 2136110. PMID 7672103.

- ^ MacIntyre, Krystal. "Mississippi abortion ban bill fails as legislators miss deadline for compromise", Jurist News Archive (2006-03-28). Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ^ "State Policy On Informed Consent for Abortion" (PDF). Guttmacher Policy Review. Fall 2007. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c "State Abortion Counseling Policies and the Fundamental Principles of Informed Consent". Guttmacher Institute. 2007-11-12. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- ^ "Do abortions cause breast cancer? Kansas State House Abortion Act invokes shaky science for political gain". Slate Magazine. 23 May 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ "Misinformed Consent: The Medical Accuracy of State-Developed Abortion Counseling Materials". 25 October 2006.

- ^ Curry, Tom. MSNBC.com ""Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-11-09. Retrieved 2011-11-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)". Retrieved 2011-11-9. - ^ a b c d e Lai, K. K. Rebecca (2019-05-15). "Abortion Bans: 8 States Have Passed Bills to Limit the Procedure This Year". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ "TRAP Laws Gain Political Traction While Abortion Clinics—and the Women They Serve—Pay the Price". Guttmacher Institute. 2013-06-27. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- ^ Tavernise, Sabrina (2019-05-15). "'The Time Is Now': States Are Rushing to Restrict Abortion, or to Protect It". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j McCann, Allison (May 23, 2017). "Seven states have only one remaining abortion clinic. We talked to the people keeping them open". Vice News. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- ^ "State legislatures see flurry of activity on abortion bills". PBS NewsHour. 2018-02-03. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- ^ a b Mississippi House of Representatives (March 19, 2021). "House Bill 1510: AN ACT TO BE KNOWN AS THE GESTATIONAL AGE ACT;..." Retrieved May 18, 2021.

(b) Except in a medical emergency or in the case of a severe fetal abnormality, a person shall not intentionally or knowingly perform, induce, or attempt to perform or induce an abortion of an unborn human being if the probable gestational age of the unborn human being has been determined to be greater than fifteen (15) weeks.

- ^ Franks, Trent (October 4, 2017). "Text; H.R.36 - 115th Congress (2017-2018): Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act". congress.gov.

- ^ a b c "Here's Where Women Have Less Access to Planned Parenthood". Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- ^ "MS HB6 - 2013 - Regular Session". LegiScan.

- ^ "2014 Regular Session - Senate Bill 2807". Mississippi Legislative Bill Status System. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ "MS SB2807 - 2014 - Regular Session". LegiScan.

- ^ "MS HB1198 - 2017 - Regular Session". LegiScan.

- ^ "MS SB2562 - 2017 - Regular Session". LegiScan.

- ^ "MS SB2584 - 2017 - Regular Session". LegiScan.

- ^ "MS HB226 - 2018 - Regular Session". LegiScan.

- ^ "MS SB2143 - 2018 - Regular Session". LegiScan.

- ^ "MS HB1509 - 2018 - Regular Session". LegiScan.

- ^ "2019 Regular Session - House Bill 529". Mississippi Legislative Bill Status System. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Ulmer, Sarah (February 5, 2019). "House and Senate pass HeartBeat bills out of Committee". Yall Politics. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ "2019 Regular Session - Senate Bill 2116". Mississippi Legislative Bill Status System. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ "2019 Regular Session - House Bill 732". Mississippi Legislative Bill Status System. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ Wagster Pettus, Emily (February 13, 2019). "Mississippi advances ban on abortion after fetal heartbeat". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

The Republican-controlled Mississippi House and Senate passed separate bills Wednesday to ban most abortions once a fetal heartbeat is detected, about six weeks into pregnancy.

- ^ "Fetal heartbeat bill heads to governor". WTOK 11 (ABC). March 19, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ Singman, Brooke (March 22, 2019). "Mississippi Gov. Bryant signs 'heartbeat bill,' enacting one of strictest abortion laws in nation". Fox News. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ^ "Mississippi bans abortion on sex, race, genetic disability". www.catholicnewsagency.com.

- ^ "Mississippi 'Personhood' Amendment Vote Fails". Huffington Post. November 8, 2011.

- ^ Phillips, Rich. "Judge lets Mississippi's only abortion clinic stay open -- for now". CNN.

- ^ Shimabukuro, Jon O. (April 10, 2018). Mississippi Court Halts Enforcement of New Abortion Law (PDF). Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Ly, Laura. "Judge temporarily blocks 15-week abortion ban in Mississippi". CNN. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

- ^ Smith, Kate (May 13, 2019). "A pregnant 11-year-old rape victim in Ohio would no longer be allowed to have an abortion under new state law". CBS News. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Quinn, Melissa (May 17, 2021). "Supreme Court takes up blockbuster case over Mississippi's 15-week abortion ban". CBS News. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Arndorfer, Elizabeth; Michael, Jodi; Moskowitz, Laura; Grant, Juli A.; Siebel, Liza (December 1998). A State-By-State Review of Abortion and Reproductive Rights. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9780788174810.

- ^ Gould, Rebecca Harrington, Skye. "The number of abortion clinics in the US has plunged in the last decade — here's how many are in each state". Business Insider. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ businessinsider (2018-08-04). "This is what could happen if Roe v. Wade fell". Business Insider (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2019-05-24. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c "When it comes to abortion, conservative women aren't a monolith". USA Today. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- ^ Holly Yan (29 May 2019). "These 6 states have only 1 abortion clinic left. Missouri could become the first with zero". CNN. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ Cates, Willard; Rochat, Roger (March 1976). "Illegal Abortions in the United States: 1972–1974". Family Planning Perspectives. 8 (2): 86–92. doi:10.2307/2133995. JSTOR 2133995. PMID 1269687.

- ^ "Guttmacher Data Center". data.guttmacher.org. Retrieved 2019-05-24.

- ^ "Views about abortion by state - Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- ^ Jr, Perry Bacon (2019-05-16). "Three Reasons There's A New Push To Limit Abortion In State Legislatures". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved 2019-05-26.

- ^ a b c d "Abortion Incidence and Services in the United States, 1995–1996". Guttmacher Institute. 2005-06-15. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2017). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2014". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 66 (24): 1–48. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6624a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 6289084. PMID 29166366.

- ^ Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2018). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2015". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 67 (13): 1–45. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6713a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMC 6289084. PMID 30462632.

- ^ Jatlaoui, Tara C. (2019). "Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2016". MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 68 (11): 1–41. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6811a1. ISSN 1546-0738. PMID 31774741.

- ^ Pesce, Nicole Lyn. "Abortion bans are spurring donations to Planned Parenthood, the National Organization for Women, and more". MarketWatch. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- ^ Bacon, John. "Abortion rights supporters' voices thunder at #StopTheBans rallies across the nation". USA Today. Retrieved 2019-05-25.