Merriam-Webster: Difference between revisions

Deltaspace42 (talk | contribs) m Reverted 1 edit by 102.215.103.28 (talk) to last revision by Danbloch |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online |

|encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica Online |

||

|date=2015 |

|date=2015 |

||

|access-date=June 24, 2015}}</ref> |

|access-date=June 24, (+1), 2015'}}</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 18:27, 8 December 2023

| |

| Parent company | Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1831 |

| Founder | George Merriam, Charles Merriam |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Headquarters location | Springfield, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Publication types | Reference books, online dictionaries |

| Owner(s) | Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. |

| Official website | www |

Merriam-Webster, Incorporated is an American company that publishes reference books and is mostly known for its dictionaries. It is the oldest dictionary publisher in the United States.[1]

In 1831, George and Charles Merriam founded the company as G & C Merriam Co. in Springfield, Massachusetts. In 1843, after Noah Webster died, the company bought the rights to An American Dictionary of the English Language from Webster's estate. All Merriam-Webster dictionaries trace their lineage to this source.

In 1964, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., acquired Merriam-Webster, Inc., as a subsidiary. The company adopted its current name, Merriam-Webster, Incorporated, in 1982.[2][3]

History

Noah Webster

In 1806, Webster published his first dictionary, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. In 1807 Webster started two decades of intensive work to expand his publication into a fully comprehensive dictionary, An American Dictionary of the English Language. To help him trace the etymology of words, Webster learned 26 languages. Webster hoped to standardize American speech, since Americans in different parts of the country used somewhat different vocabularies and spelled, pronounced, and used words differently.

Webster completed his dictionary during his year abroad in 1825 in Paris, and at the University of Cambridge. His 1820s book contained 70,000 words, of which about 12,000 had never appeared in a dictionary before. As a spelling reformer, Webster believed that English spelling rules were unnecessarily complex, so his dictionary introduced American English spellings, replacing colour with color, waggon with wagon, and centre with center. He also added American words, including skunk and squash, that did not appear in British dictionaries. At the age of 70 in 1828, Webster published his dictionary; it sold poorly, with only 2,500 copies, and put him in debt. However, in 1840, he published the second edition in two volumes with much greater success.

Merriam as publisher

In 1843, after Webster's death, George Merriam and Charles Merriam secured publishing and revision rights to the 1840 edition of the dictionary. They published a revision in 1847, which did not change any of the main text but merely added new sections, and a second update with illustrations in 1859. In 1864, Merriam published a greatly expanded edition, which was the first version to change Webster's text, largely overhauling his work yet retaining many of his definitions and the title "An American Dictionary". This began a series of revisions that were described as being "unabridged" in content. In 1884 it contained 118,000 words, "3000 more than any other English dictionary".[4]

With the edition of 1890, the dictionary was retitled Webster's International. The vocabulary was vastly expanded in Webster's New International editions of 1909 and 1934, totaling over half a million words, with the 1934 edition retrospectively called Webster's Second International or simply "The Second Edition" of the New International.

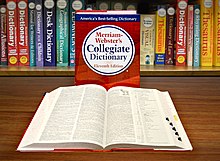

The Collegiate Dictionary was introduced in 1898 and the series is now in its eleventh edition. Following the publication of Webster's International in 1890, two Collegiate editions were issued as abridgments of each of their Unabridged editions. Merriam overhauled the dictionary again with the 1961 Webster's Third New International under the direction of Philip B. Gove, making changes that sparked public controversy. Many of these changes were in formatting, omitting needless punctuation, or avoiding complete sentences when a phrase was sufficient. Others, more controversial, signaled a shift from linguistic prescriptivism and towards describing American English as it was used at that time.[5]

With the ninth edition (Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary (WNNCD), published in 1983), the Collegiate adopted changes which distinguish it as a separate entity rather than merely an abridgment of the Third New International (the main text of which has remained virtually unrevised since 1961). Some proper names were returned to the word list, including names of Knights of the Round Table. The most notable change was the inclusion of the date of the first known citation of each word, to document its entry into the English language. The eleventh edition (published in 2003) includes more than 225,000 definitions, and more than 165,000 entries. A CD-ROM of the text is sometimes included. This dictionary is preferred as a source "for general matters of spelling" by the influential The Chicago Manual of Style, which is followed by many book publishers and magazines in the United States. The Chicago Manual states that it "normally opts for" the first spelling listed.[6]

The G. & C. Merriam Company lost its right to exclusive use of the name "Webster" after a series of lawsuits placed that name in public domain. Its name was changed to "Merriam-Webster, Incorporated", with the publication of Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary in 1983. Previous publications had used "A Merriam-Webster Dictionary" as a subtitle for many years and will be found on older editions.

Since the 1940s, the company has added many specialized dictionaries, language aides, and other references to its repertoire. The company has been a subsidiary of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., since 1964.

The dictionary maintains an active social media presence, where it frequently posts dictionary related content as well as its takes on politics. Its Twitter account has frequently used dictionary jargon to criticize and lampoon the Trump administration.[7][8] In one viral tweet, Merriam Webster subtly accused Kyle Rittenhouse of fake crying at his trial.[9]

Services

In 1996, Merriam-Webster launched its first website, which provided free access to an online dictionary and thesaurus.[10]

Merriam-Webster has also published dictionaries of synonyms, English usage, geography (Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary), biography, proper names, medical terms, sports terms, slang, Spanish/English, and numerous others. Non-dictionary publications include Collegiate Thesaurus, Secretarial Handbook, Manual for Writers and Editors, Collegiate Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia of Literature, and Encyclopedia of World Religions.

On February 16, 2007, Merriam-Webster announced the launch of a mobile dictionary and thesaurus service developed with mobile search-and-information provider AskMeNow. Consumers use the service to access definitions, spelling and synonyms via text message. Services also include Merriam-Webster's Word of the Day—and Open Dictionary, a wiki service that provides subscribers the opportunity to create and submit their own new words and definitions.[11]

Pronunciation guides

The Merriam-Webster company once used a unique set of phonetic symbols in their dictionaries—intended to help people from different parts of the United States learn how to pronounce words the same way as others who spoke with the same accent or dialect did. Unicode accommodated IPA symbols from Unicode version 1.1 published in 1993, but did not support the phonetic symbols specific to Merriam-Webster dictionaries until Unicode version 4.0 published in 2003. Hence, to enable computerized access to the pronunciation without having to rework all dictionaries to IPA notation, the online services of Merriam-Webster specify phonetics using a less-specific set of ASCII characters.

Writing entries

Merriam creates entries by finding uses of a particular word in print and recording them in a database of citations.[5] Editors at Merriam spend about an hour a day looking at print sources, from books and newspapers to less formal publications, like advertisements and product packaging, to study the uses of individual words and choose things that should be preserved in the citation file. Merriam-Webster's citation file contains more than 16 million entries documenting individual uses of words. Millions of these citations are recorded on 3-by-5 cards in their paper citation files. The earliest entries in the paper citation files date back to the late 19th century. Since 2009, all new entries are recorded in an electronic database.[5]

See also

- Kory Stamper, noted lexicographer/editor/social media personality at Merriam-Webster

- Lists of Merriam-Webster's Words of the Year

- Webster's Dictionary

- Webster's Third New International Dictionary

References

- ^ Correa, Carla (November 3, 2021). "Attention, New Englanders: Fluffernutter Is Now a Word". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2015. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ "An American Dictionary of the English Language". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2015. Retrieved June 24, (+1), 2015'.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ^ "Webster's Unabridged". The Week: A Canadian Journal of Politics, Literature, Science and Arts. 1 (10): 160. February 11, 1884. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- ^ a b c Fatsis, Stefan (January 12, 2015). "The Definition of a Dictionary". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th edition, New York and London: University of Chicago Press, 2003, Chapter 7: "Spelling, Distinctive Treatment of Words, and Compounds", Section 7.1 "Introduction", p. 278.

- ^ Pitofsky, Marina (September 13, 2019). "Merriam-Webster: A 200-year-old dictionary offers hot political takes on Twitter". The Hill. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "18 Times Merriam-Webster Was a Political Troll". Time. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Kyle Rittenhouse Gets Trolled By Merriam-Webster Dictionary for Crying in Court".

- ^ "Timeline: Merriam-Webster Milestones", Merriam-Webster, archived from the original on January 13, 2015, retrieved October 14, 2018

- ^ Trusca, Sorin (February 16, 2007). "AskMeNow and Merriam-Webster Launch Mobile Dictionary". Softpedia. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

External links

- Official website of Merriam-Webster

- G. & C. Merriam Company Collection at the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections