Jahanara Imam: Difference between revisions

Smkamal1942 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

m →External links: Fixed link |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*[http://banglapedia.search.com.bd/HT/I_0028.htm A biography on Banglapedia] |

*[http://banglapedia.search.com.bd/HT/I_0028.htm A biography on Banglapedia] |

||

*[http://www.sitesofconscience.org/ |

*[http://www.sitesofconscience.org/index.php/sites/liberation-war-museum/how-is-it-remembered/jahanara-imam/en/ A short biography at International Coalition of Historic Site Museums of Conscience] |

||

[[Category:1929 births|Imam, Jahanara]] |

[[Category:1929 births|Imam, Jahanara]] |

||

Revision as of 03:08, 26 January 2008

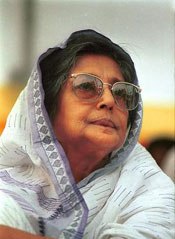

Jahanara Imam (Template:Lang-bn) (May 3, 1929—June 26, 1994) was a Bangladeshi writer and political activist. She is most widely remembered for her endeavour to bring war criminals of the Bangladesh Liberation War to trial. She was popularly known as "Shaheed Janani"(Mother of Martyrs).

Biography

From http://www.adhunika.org

Jahanara Imam was born in a progressive Muslim family in Murshidabad, in West Bengal, India. She was the eldest daughter. Her father Syed Abdul Ali was a Civil Servant in the Bengal Civil Service and she lived in many different parts of Bengal - wherever her father was posted. She had a very liberal upbringing and received a liberal education. She was a very spirited girl, very unusual among her contemporaries, right from her childhood. Her father recognized this and made sure that she received the highest possible education. Her mother Hamida Ali, who spent her entire life looking after her family and bringing up her children, also had high ambitions for her daughter. At that time there were lots of social pressure against Muslim women’s higher studies but she was determined that Jahanara would not end up like other women of her time. Her parents' ambitions and their belief in education for women left a deep impression in the later life of Jahanara Imam.

After finishing her studies in 1945 in Carmichael College in Rangpur, Jahanara Imam went to Lady Brabourne College of Calcutta University in Calcutta and in 1947 obtained her Bachelor's Degree. She was an activist even during her Lady Brabourne College days. After the partition of India, she joined her family in Mymensingh in what became East Pakistan and started teaching at Bidyamoyee Girl's School.

In 1948, Jahanara Imam married Shariful Alam Imam Ahmed, a Civil Engineer, whom she met in Rangpur while studying at Carmichael College. They settled in Dhaka and she joined Siddheswari Girl's School as Head Mistress. She was instrumental in transforming the school from its humble beginnings into one of the top girls' schools in Dhaka.

Jahanara Imam was the first editor of the monthly women’s magazine called “Khawateen”. It started its publication in 1952 and she ran it successfully for several years.

In 1960 she gave up her job as Head Mistress to concentrate on bringing up her two sons Rumi and Jami born in 1952 and 1954 respectively. She said to herself “I have given education to thousands of school children, now I should spent some time to bring up my own children”, and she did bring them up to her own high standards.

During this time Jahanara Imam finished her Master's Degree in Bengali Language and Literature and a Bachelor's Degree in Education from Dhaka University. After that she went back to full-time teaching again. From 1966 to 1968 she worked as a Lecturer in the Teacher’s Training College in Dhaka. From 1970 she also taught for several years on a part-time basis in the Institute of Modern Language in Dhaka University.

She spent a significant part of her life as an educationist. She visited the USA in 1964-65 as a Fulbright Scholar to San Diego University and again in 1977 under the International Visitors Program at the invitation of the government of United States of America.

In 1971, following the Pakistan army crackdown on 25 March, the Bangladesh Liberation war broke out. Many young men joined the liberation struggle. Her elder son Rumi,19 years old also joined Mukti Bahini to become a Mukti Joddha (Freedom Fighter). Bottled up in Dhaka with no news about his whereabouts, Jahanara Imam felt anxious about her son. During the nine months of war, she wrote a diary, detailing personal events as well as her own feelings about the war.

Rumi took part in many daring actions against Pakistan army. Unfortunately, he was to be picked up by Pakistan army, never to be seen again. Her husband and her younger son Jami along with other male members of the family were also picked up for interrogation and were tortured. Her husband Sharif Imam returned home as a broken man only to die 3 days before Bangladesh became free on 16 December 1971.

After Bangladesh achieved independence, Jahanara Imam started her literary career. During this time she also traveled extensively to Europe, USA and Canada. In 1986 she published her wartime diary as “Ekatturer Dinguli” (The days of Seventy One). Publication of this book was a seminal event in the history of Bangladesh. It proved to be a catalyst for the renewal of faith in the destiny of Bangladesh as an independent nation.

Jahanara Imam's diary, in some respect like that of Anne Frank, was the personal account of a tragedy whose true magnitude might never be fully fathomed by those who did not experience it first hand. Her simple style of writing touched everybody’s heart, particularly those families' that had lost somebody during the war. Her diary became their own diary; witness to their own suffering. The Freedom Fighters who felt that they were let down by the nation, woke up again. They called her “Shaheed Janani” (Mother of Martyrs). “Ekatturer Dinguli” electrified Bangladesh as no other book ever did.

When you reflect on her life, you recall the glamour that once defined her being. It was the kind of glamour that did not come with the glitter one associates with it. It was indeed a way of sophisticated living that people aspire to. In her young days she was known for her beauty and elegance. She was known as Suchitra Sen of Dhaka, the famous Indian Bengali film star. After 1971 her life could never be the same again. The glamour that once defined her being disappeared and a new life started.

Jahanara Imam was a prolific writer and made great contribution to Bengali literature. She was honoured and awarded several times. In 1988 she received an award from Bangladesh Writer’s Association. In 1991 in recognition to her literary works she received the prestigious honour in Bengali literature “Bangla Academy Literary Award” from Bangla Academy. Prestigious daily newspaper “Ajker Kagoj” hailed her as the Greatest Freedom Fighter of 14th century in Bengali Calendar. In 1997 and 1998 she received posthumously Independence Award and Rokeya Award respectively.

In 1981 she was diagnosed with mouth cancer. But the disease could not stop her activities. She continued to write stories, novels and diaries as well as continuing her involvement with the Freedom Fighters. She had to have several operations which made speaking difficult. She refused to let cancer destroy her spirit. She became the leader of “Ghatak Dalal Nirmul Committee” a political movement to try the 1971 war criminals.

Jahanara Imam died in Detroit, USA on 26 June 1994. She was buried in Dhaka as she had wished. To show respect to Shaheed Janani, nearly quarter of a million people attended her funeral.

Effort to try war criminals

As Bangladesh's ruler, President Ziaur Rahman (1975-1981) enacted several controversial measures, ostensibly to win the support of Islamic political parties and opponents of the Awami League. In 1978 he revoked the ban on the Jamaat-e-Islami, which was widely believed to have collaborated with the Pakistani army and committed war crimes against civilians.

Golam Azam, the exiled chief of the Jammat-e-Islami, was allowed to come back in July 1978 with a Pakistani passport on a visitor's visa, and he remained in Bangladesh following its expiry. But he stayed back with the blessings of President Zia and resumed organizing the hitherto banned Islamic fundamentalist: Jamaat-e-Islam. He was not brought to trial over his alleged role in committing wartime atrocities, and to make it worse eventually other Jamaat leaders were appointed in ministerial posts. Zia also rehabilitated Shah Azizur Rahman, a high-profile opponent of the creation of Bangladesh. In 1991 December Golam Azam, still a Pakistani citizen, was elected the Amir of Jamaat-e-Islam. Despite nationwide protest against Golam Azam's officially chairing the political party, Prime Minister Khaleda Zia’s government ignored the constitutional violation on the part of the Jamaatis. These shameless acts were insults to the very essence of Bangladesh liberation and brought huge condemnation from the people of Bangladesh and the freedom fighters who were getting disillusioned with this type of immoral politics.

During this time Jahanara Imam was leading a relatively quiet life busy with her literary works, but she could not take it any more. Never a political person, she came into political forefront of Bangladesh. She organized the Ghatak-Dalal Nirmul Committee (Committee to exterminate the Killers and Collaborators), and became its public face. The committee called for trial of people who committed crimes against humanity in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War in collaboration with the Pakistani forces. In a highly symbolic act, Ghatak-Dalal Nirmul Committee set up mock trials in Dhaka in March 1992 known as Gonoadalot (Court of the people) and sentenced war criminals. This was a symbolic verdict. Jahanara Imam and 24 other intellectuals were charged with treason. This charge was, however, dropped in 1996 after her death by the President Mohammed Habibur Rahman of the Caretaker government of that time.

Though Jahanara Imam and her associates were seeking to try crimes 20 years old at that point, their acts caused deep reverberations in the political arena of Bangladesh. But it was necessary. Her cancer was getting worse. Even as physical infirmity claimed her, she went round the country reminding Bengalis of the cause their sons and daughters and parents died for. She reminded the population that the genocide had not been forgotten, that Pakistan’s collaborators needed to be brought to justice. During her campaign she received great help from Awami League and it was understood that if Awami League came to power they would take up her cause. Awami League did come to power in 1996 under the Premiership of Sheikh Hasina but unfortunately they came into some sort of political understanding with Jamaat-e-Islam and nothing was done. In the end there was no difference between Khaleda Zia or Sheikh Hasina. It was good that she did not live to see this.

It did not matter. She spread her message to the people, exposed the criminals to the public and it was left to the politicians and their morality. She arrived at the political arena like a meteor and gave new lease of life to the people who lost their self-esteem in the politics of Bangladesh.

Last Message

Jahanara Imam’s last message to the nation written from her deathbed before she merged with eternity:

My Appeal and Directives to the people of Bangladesh (From Shahid Janani Jahanara Imam)

My fellow warriors,

You have been fighting the evil forces of Golam Azam and his war criminals

of 1971, along with the detractors of a free Bangladesh for the last three

years. As a nation of Bangalees, your unity and courage has been

unparallel. I was with you at the start of our struggle. Our resolve was

to remain in battle until we had achieved our objective. Stricken with the

fatal disease of cancer, I am now facing my final days. I have kept my

resolve. I did not leave the battle. But I cannot stop the inevitable

March of death. Therefore, I once again remind you of our resolve to fight

until our goal is attained. You must fulfill your commitment. You must

stand united and fight to the very end. Even though I will not be among

you. I will know that you--- my millions of Bangalee children---- will

live in a free Golden Bengal with your sons and daughters.

We still have a long and arduous road ahead. People from all walks of life

has joined this battle. People from different political and cultural

groups, freedom fighters, women, and students, and youths have all

committed themselves to the battle. And I know that there is no one more

committed than the people. People are power. So I commit the

responsibility of the fight to bring Golam Azam and the war criminals of

1971 to justice and to continue to champion the Spirit of the Liberation

War to you--- the people of Bangladesh. For certain, victory will be ours.

Literary Works

- Anya Jiban (1985) (Other life)

- Ekattorer Dingulee (1986) (The days of 1971)

- Jiban Mrityu (1988) (Life and death)

- Buker Bhitare Agun (1990) (Fire in my heart)

- Nataker Abasan (1990) (End of drama)

- Dui Meru (1990) (Two poles)

- Cancer-er Sange Bosobas (1991) (Living with cancer)

- Prabaser Dinalipi (1992) (Life abroad)