Islamic world contributions to Medieval Europe: Difference between revisions

m →See also: added link |

|||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Latin translations of the 12th century]] |

* [[Latin translations of the 12th century]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* [[Madrasah#Universities and colleges|Madrasah: Universities and colleges]] |

|||

==Notes== |

==Notes== |

||

Revision as of 07:41, 8 March 2008

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

![]() Wherever the term islamic is found in this article, it should be replaced with Arabic.

Wherever the term islamic is found in this article, it should be replaced with Arabic.

The Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe were important and numerous. These contributions affected such varied areas as sciences, techniques, medecine, food, music or vocabulary. From the 10th to the 13th century, Europe literally absorbed vast quantities of knowledge from the Islamic civilization.[2] This had considerable effects on the development of the West, leading in many ways to the achievement of the Renaissance.[3]

Transmission routes

The points of contact between Europe and Islamic lands were multiple during the Middle Ages. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe were in Sicilia, and in Toledo, Spain (with Gerard of Cremone, 1114-1187). In Sicilia, an intense Arabo-Normand culture developed, examplified by rulers such as Roger II, who had Islamic soldiers, poets and scientists at his court. One of the greatest geographical treatises of the Middle Ages was written by the Maroccan Idrisi for Roger, and entitled Kitab Rudjdjar ("The book of Roger").[4]

The Crusades also intensified exchanges between Europe and the Levant, with Italian City Republics taking a great in these exchanges. In the Levant, such cities as Antioch, Arab and Latin cultures intermixed intensively.[5]

Classical knowledge

Following the fall of the Roman Empire and the dawn of the Middle Ages, many texts from Classical Antiquity had been lost to the Europeans. In the Middle East however, many of these Greek texts (such as Aristotle) were translated from Greek into Syriac during the 6th and the 7th century by Nestorian, Melkites or Jacobite monks living in Palestine, or by Greeks exiles from Athens or Edessa who visited Islamic Universities. Many of these texts however were then kept, translated, and developed upon by the Islamic world, especially in centers of learning such as Baghdad, where a “House of Wisdom”, with thousands of manuscripts existed as soon as 832. These texts were translated again into European languages during the Middle Ages.[6] Eastearn Christians played an important role in exploiting this knowledge, especially through the Christian Aristotelician School of Baghdad in the 11th and 12th centuries.

These texts were translated back into Latin in multiple ways. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe were in Sicilia, and in Toledo, Spain (with Gerard of Cremone, 1114-1187). The Crusades also intensified exchanges between Europe and the Levant. Burgondio of Pise (died in 1193) who discovered in Antioch lost texts of Aristotle and translated them in Latin.

Islamic sciences

Islam was not however a simple retransmitter of knowledge from antiquity. It also developed it own sciences, such as algebra, arithmetics, trigonometry, geology, which were later transmitted to the West.[7] Stefan of Pise translated into Latin around 1127 an Arab manual of medical theory. Modern Arabian numbers were developed by al-Khwarizmi (hence the word “Algorithm”) in the 9th century, and introduced in Europe by Leonardo Fibonacci (1170-1250).[8] A translation of the algebra of al-Kharizmi if known as early as 1145, by a certain Robert of Chester. Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham 980-1037) compiled treaties on optical sciences, which were used as references by Newton and Descartes. Medical sciences were also highly developed in Islam as testified by the Crusaders, who relied on Arab doctors on numerous occasions. Joinville reports he was saved in 1250 by a “Saracen” doctor.[9]

Islamic techniques

In the 12th century Europe owed Islam an agricultural revolution, due to the progressive introduction into Europe of various unknown fruits: the artichoke, spinachs, aubergines, peaches, apricots.[10] Various mechanical and agricutural equipments were adopted from Islamic lands such as the noria or the windmill. Numerous new techniques in clothing, as well as new materials were also introduced: muslin, taffetas, satin, skirts. Trade mechanisms were also transmitted: tarifs, customs, bazars, magazins. Many of the music instruments used in the West also had Arab origins: the lute, the rebec, the harp.

Vocabulary

The adoption of the techniques and materials from the Islamic world is reflected in the origin of many of the words now in use in the Western world.

- Algebra, which comes from al-djar

- Alchemy/ Chemistry, from al kemi الخيمياء

- Almanach, from al-manakh (timetables)

- Admiral, from amir al-bahr امير البحر (“Prince of the sea”)

- Avarie (French for "ship damage"), from awar ("damage")

- Baldaquin, from a tissue material made in Baghdad.

- Coffee, from Kahwa

- Camphor, from kafur

- Amber, from al-anbar

- Artichoke, from al-karchouf

- Chiffre (French for "number"), from sifr (meaning "zero")

- Cotton, from koton

- Sugar, from soukkar

- Magazin, from makhâzin

- Mat (as in "Chess mat"), from mât ("Death")

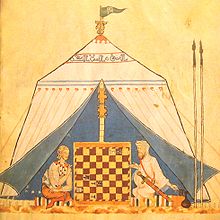

- Hazard, from az-zahr (game of dice)

- Orange, from nârandj

- Lacquer, from lakk

- Luth, from al-ud

- Racket, from râhat (palm of the hand)

- Sorbet, from sharab

See also

- Latin translations of the 12th century

- Islamic Golden Age

- Islamic science: Influence on European science

- Sharia: Classical Islamic law

- Madrasah: Universities and colleges

Notes

References

- Lebedel, Claude, "Les Croisades, origines et conséquences", 2006, Editions Ouest-France, ISBN 2737341361

- Roux, Jean-Paul, "Les explorateurs au Moyen-Age", Hachette, 1985, ISBN 2012793398

- Lewis, Bernard, "Les Arabes dans l'histoire", 1993, Flammarion, ISBN 2080813625