Islamic world contributions to Medieval Europe: Difference between revisions

m →Islamic sciences: added link |

m →Islamic sciences: added link |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

==Islamic sciences== |

==Islamic sciences== |

||

{{see|Latin translations of the 12th century}} |

|||

{{see also|Islamic science}} |

{{see also|Islamic science}} |

||

Revision as of 07:46, 8 March 2008

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

![]() Wherever the term islamic is found in this article, it should be replaced with Arabic.

Wherever the term islamic is found in this article, it should be replaced with Arabic.

The Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe were important and numerous. These contributions affected such varied areas as sciences, techniques, medecine, food, music or vocabulary. From the 10th to the 13th century, Europe literally absorbed vast quantities of knowledge from the Islamic civilization.[2] This had considerable effects on the development of the West, leading in many ways to the achievement of the Renaissance.[3]

Transmission routes

The points of contact between Europe and Islamic lands were multiple during the Middle Ages. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe were in Sicilia, and in Toledo, Spain (with Gerard of Cremone, 1114-1187). In Sicilia, an intense Arabo-Normand culture developed, examplified by rulers such as Roger II, who had Islamic soldiers, poets and scientists at his court. One of the greatest geographical treatises of the Middle Ages was written by the Maroccan Idrisi for Roger, and entitled Kitab Rudjdjar ("The book of Roger").[4]

The Crusades also intensified exchanges between Europe and the Levant, with Italian City Republics taking a great in these exchanges. In the Levant, such cities as Antioch, Arab and Latin cultures intermixed intensively.[5]

Classical knowledge

Following the fall of the Roman Empire and the dawn of the Middle Ages, many texts from Classical Antiquity had been lost to the Europeans. In the Middle East however, many of these Greek texts (such as Aristotle) were translated from Greek into Syriac during the 6th and the 7th century by Nestorian, Melkites or Jacobite monks living in Palestine, or by Greeks exiles from Athens or Edessa who visited Islamic Universities. Many of these texts however were then kept, translated, and developed upon by the Islamic world, especially in centers of learning such as Baghdad, where a “House of Wisdom”, with thousands of manuscripts existed as soon as 832. These texts were translated again into European languages during the Middle Ages.[6] Eastearn Christians played an important role in exploiting this knowledge, especially through the Christian Aristotelician School of Baghdad in the 11th and 12th centuries.

These texts were translated back into Latin in multiple ways. The main points of transmission of Islamic knowledge to Europe were in Sicilia, and in Toledo, Spain (with Gerard of Cremone, 1114-1187). The Crusades also intensified exchanges between Europe and the Levant. Burgondio of Pise (died in 1193) who discovered in Antioch lost texts of Aristotle and translated them in Latin.

Islamic sciences

Islam was not however a simple retransmitter of knowledge from antiquity. It also developed it own sciences, such as algebra, arithmetics, trigonometry, geology, which were later transmitted to the West.[7] Stefan of Pise translated into Latin around 1127 an Arab manual of medical theory. Modern Arabian numbers were developed by al-Khwarizmi (hence the word “Algorithm”) in the 9th century, and introduced in Europe by Leonardo Fibonacci (1170-1250).[8] A translation of the algebra of al-Kharizmi if known as early as 1145, by a certain Robert of Chester. Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham 980-1037) compiled treaties on optical sciences, which were used as references by Newton and Descartes. Medical sciences were also highly developed in Islam as testified by the Crusaders, who relied on Arab doctors on numerous occasions. Joinville reports he was saved in 1250 by a “Saracen” doctor.[9]

Contributing to the growth of European science was the major search by European scholars for new learning which they could only find among Muslims, especially in Islamic Spain and Sicily. These scholars translated new scientific and philosophical texts from Arabic into Latin.

One of the most productive translators in Spain was Gerard of Cremona, who translated 87 books from Arabic to Latin,[10] including Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī's On Algebra and Almucabala, Jabir ibn Aflah's Elementa astronomica,[11] al-Kindi's On Optics, Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī's On Elements of Astronomy on the Celestial Motions, al-Farabi's On the Classification of the Sciences,[12] the chemical and medical works of Razi,[13] the works of Thabit ibn Qurra and Hunayn ibn Ishaq,[14] and the works of Arzachel, Jabir ibn Aflah, the Banū Mūsā, Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam, Abu al-Qasim, and Ibn al-Haytham (including the Book of Optics).[10]

Other Arabic works translated into Latin during the 12th century include the works of Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī and Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī (including The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing),[11] the works of Abu al-Qasim (including the al-Tasrif),[15][10] Muhammad al-Fazari's Great Sindhind (based on the Surya Siddhanta and the works of Brahmagupta),[16] the works of Razi and Avicenna (including The Book of Healing and The Canon of Medicine),[17] the works of Averroes,[15] the works of Thabit ibn Qurra, al-Farabi, Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī, Hunayn ibn Ishaq, and his nephew Hubaysh ibn al-Hasan,[18] the works of al-Kindi, Abraham bar Hiyya's Liber embadorum, Ibn Sarabi's (Serapion Junior) De Simplicibus,[15] the works of Qusta ibn Luqa,[19] the works of Maslamah Ibn Ahmad al-Majriti, Ja'far ibn Muhammad Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi, and al-Ghazali,[10] the works of Nur Ed-Din Al Betrugi, including On the Motions of the Heavens,[20][13] Ali ibn Abbas al-Majusi's medical encyclopedia, The Complete Book of the Medical Art,[13] Abu Mashar's Introduction to Astrology,[21] the works of Maimonides, Ibn Zezla (Byngezla), Masawaiyh, Serapion, al-Qifti, and Albe'thar.[22] Abū Kāmil Shujā ibn Aslam's Algebra,[11] the chemical works of Geber, and the De Proprietatibus Elementorum, an Arabic work on geology written by a pseudo-Aristotle.[13] By the beginning of the 13th century, Mark of Toledo translated the Qur'an and various medical works.[23]

Fibonacci presented the first complete European account of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system from Arabic sources in his Liber Abaci (1202).[13] Al-Khazini's Zij as-Sanjari was translated into Greek by Gregory Choniades in the 13th century and was studied in the Byzantine Empire.[24] The astronomical corrections to the Ptolemaic model made by al-Battani and Averroes and the non-Ptolemaic models produced by Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi (Urdi lemma), Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī (Tusi-couple) and Ibn al-Shatir were later adapted into the Copernican heliocentric model. Al-Kindi's (Alkindus) law of terrestrial gravity influenced Robert Hooke's law of celestial gravity, which in turn inspired Newton's law of universal gravitation. Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī's Ta'rikh al-Hind and Kitab al-qanun al-Mas’udi were translated into Latin as Indica and Canon Mas’udicus respectively. Ibn al-Nafis' Commentary on Compound Drugs was translated into Latin by Andrea Alpago (d. 1522), who may have also translated Ibn al-Nafis' Commentary on Anatomy in the Canon of Avicenna, which first described pulmonary circulation and coronary circulation, and which may have had an influence on Michael Servetus, Realdo Colombo and William Harvey.[25] Translations of the algebraic and geometrical works of Ibn al-Haytham, Omar Khayyám and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī were later influential in the development of non-Euclidean geometry in Europe from the 17th century.[26][27] Ibn Tufail's Hayy ibn Yaqdhan was translated into Latin by Edward Pococke in 1671 and into English by Simon Ockley in 1708 and became "one of the most important books that heralded the Scientific Revolution."[28] Ibn al-Baitar's Kitab al-Jami fi al-Adwiya al-Mufrada also had an influence on European botany after it was translated into Latin in 1758.[29]

Islamic techniques

In the 12th century Europe owed Islam an agricultural revolution, due to the progressive introduction into Europe of various unknown fruits: the artichoke, spinachs, aubergines, peaches, apricots.[30] Various mechanical and agricutural equipments were adopted from Islamic lands such as the noria or the windmill. Numerous new techniques in clothing, as well as new materials were also introduced: muslin, taffetas, satin, skirts. Trade mechanisms were also transmitted: tarifs, customs, bazars, magazins. Many of the music instruments used in the West also had Arab origins: the lute, the rebec, the harp.

Vocabulary

The adoption of the techniques and materials from the Islamic world is reflected in the origin of many of the words now in use in the Western world.

- Algebra, which comes from al-djar

- Alchemy/ Chemistry, from al kemi الخيمياء

- Almanach, from al-manakh (timetables)

- Admiral, from amir al-bahr امير البحر (“Prince of the sea”)

- Avarie (French for "ship damage"), from awar ("damage")

- Baldaquin, from a tissue material made in Baghdad.

- Coffee, from Kahwa

- Camphor, from kafur

- Amber, from al-anbar

- Artichoke, from al-karchouf

- Chiffre (French for "number"), from sifr (meaning "zero")

- Cotton, from koton

- Sugar, from soukkar

- Magazin, from makhâzin

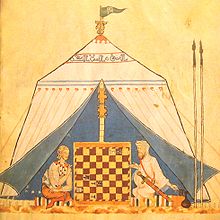

- Mat (as in "Chess mat"), from mât ("Death")

- Hazard, from az-zahr (game of dice)

- Orange, from nârandj

- Lacquer, from lakk

- Luth, from al-ud

- Racket, from râhat (palm of the hand)

- Sorbet, from sharab

See also

- Latin translations of the 12th century

- Islamic Golden Age

- Islamic science: Influence on European science

- Sharia: Classical Islamic law

- Madrasah: Universities and colleges

Notes

- ^ Lebedel, p.109

- ^ Lebedel, p.109

- ^ ”Without contacts with the arab culture, Renaissance could probably not have happened in the 15th and 16th century”, Lebedel, p.109

- ^ Lewis, p.148

- ^ Lebedel, p.109-111

- ^ Lebedel, p.109

- ^ Lebedel, p.109

- ^ Lebedel, p.111

- ^ Lebedel, p.112

- ^ a b c d Salah Zaimeche (2003). Aspects of the Islamic Influence on Science and Learning in the Christian West, p. 10. Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation.

- ^ a b c V. J. Katz, A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, p. 291.

- ^ For a list of Gerard of Cremona's translations see: Edward Grant (1974) A Source Book in Medieval Science, (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Pr.), pp. 35-8 or Charles Burnett, "The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century," Science in Context, 14 (2001): at 249-288, at pp. 275-281.

- ^ a b c d e Jerome B. Bieber. Medieval Translation Table 2: Arabic Sources, Santa Fe Community College.

- ^ D. Campbell, Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages, p. 6.

- ^ a b c D. Campbell, Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages, p. 3.

- ^ G. G. Joseph, The Crest of the Peacock, p. 306.

- ^ M.-T. d'Alverny, "Translations and Translators," pp. 444-6, 451

- ^ D. Campbell, Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages, p. 4-5.

- ^ D. Campbell, Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages, p. 5.

- ^ Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexicon

- ^ Charles Burnett, ed. Adelard of Bath, Conversations with His Nephew, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), p. xi.

- ^ D. Campbell, Arabian Medicine and Its Influence on the Middle Ages, p. 4.

- ^ M.-T. d'Alverny, "Translations and Translators," pp. 429, 455

- ^ David Pingree (1964), "Gregory Chioniades and Palaeologan Astronomy", Dumbarton Oaks Papers 18, p. 135-160.

- ^ Anatomy and Physiology, Islamic Medical Manuscripts, United States National Library of Medicine.

- ^ D. S. Kasir (1931). The Algebra of Omar Khayyam, p. 6-7. Teacher's College Press, Columbia University, New York.

- ^ Boris A. Rosenfeld and Adolf P. Youschkevitch (1996), "Geometry", p. 469, in (Morelon & Rashed 1996, pp. 447–494)

- ^ Samar Attar, The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment: Ibn Tufayl's Influence on Modern Western Thought, Lexington Books, ISBN 0739119893.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

McNeilwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Roux, p. 47

References

- Lebedel, Claude, "Les Croisades, origines et conséquences", 2006, Editions Ouest-France, ISBN 2737341361

- Roux, Jean-Paul, "Les explorateurs au Moyen-Age", Hachette, 1985, ISBN 2012793398

- Lewis, Bernard, "Les Arabes dans l'histoire", 1993, Flammarion, ISBN 2080813625