Hourglass: Difference between revisions

SoxBot III (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible test edit(s) by 80.85.96.4 to older version. Was this a mistake? (BOT EDIT) |

m Add pictures: Budapest timewheel |

||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

The sandglass is still widely used as the kitchen [[egg timer]]; for cooking eggs, a three minute timer is typical,<ref name="Herbst">{{cite book | title=[[The New Food Lover's Companion]]| last=Herbst| first=Sharon Tyler| authorlink=Sharon Tyler Herbst| year=2001| publisher=Barron's Educational Series}}</ref> hence the name "egg timer" for three minute hourglasses. Egg timers are sold widely as souvenirs,{{Fact|date=March 2008}} and games such as [[Boggle]] also make use of it. |

The sandglass is still widely used as the kitchen [[egg timer]]; for cooking eggs, a three minute timer is typical,<ref name="Herbst">{{cite book | title=[[The New Food Lover's Companion]]| last=Herbst| first=Sharon Tyler| authorlink=Sharon Tyler Herbst| year=2001| publisher=Barron's Educational Series}}</ref> hence the name "egg timer" for three minute hourglasses. Egg timers are sold widely as souvenirs,{{Fact|date=March 2008}} and games such as [[Boggle]] also make use of it. |

||

[[Image:Budapest timewheel 02.jpg|thumb|200px|The [[Timewheel]] in [[Budapest]]]] |

|||

Sand timers are also sometimes used in games such as [[Pictionary]] to implement a time constraint on players completing an action. |

Sand timers are also sometimes used in games such as [[Pictionary]] to implement a time constraint on players completing an action. |

||

===Largest sandglasses=== |

===Largest sandglasses=== |

||

The size of a sandglass is not necessarily the deciding factor for its running time. However, if its running time is to amount to several days or weeks, it will need to be fairly large. Two such giants include the [[Timewheel]] in [[Budapest]] and the sandglass at the [http://www.kanko-otakara.jp/webapps/Contribute/Parser.do?codes=32|0803165507|324221&prefix=02x01_9MCKI5238zP&l_code=02 sand museum] in the Japanese city of Nima. At eight and six metres in height respectively and a running time of one year, they are among the world's largest chronometers. Another giant has been standing at the [[Red Square]] in [[Moscow]] since July 2008. At 11.90 m in height and weighing 40 tonnes, this is likely the largest sandglass in the world. By way of comparison the smallest sandglass in the world is just 2.4 cm high. It was made in 1992 in [[Hamburg]] and takes slightly less than 5 seconds for a single run through.{{fact|date=July 2008}} |

The size of a sandglass is not necessarily the deciding factor for its running time. However, if its running time is to amount to several days or weeks, it will need to be fairly large. Two such giants include the [[Timewheel]] in [[Budapest]] and the sandglass at the [http://www.kanko-otakara.jp/webapps/Contribute/Parser.do?codes=32|0803165507|324221&prefix=02x01_9MCKI5238zP&l_code=02 sand museum] in the Japanese city of Nima. At eight and six metres in height respectively and a running time of one year, they are among the world's largest chronometers. Another giant has been standing at the [[Red Square]] in [[Moscow]] since July 2008. At 11.90 m in height and weighing 40 tonnes, this is likely the largest sandglass in the world. By way of comparison the smallest sandglass in the world is just 2.4 cm high. It was made in 1992 in [[Hamburg]] and takes slightly less than 5 seconds for a single run through.{{fact|date=July 2008}} |

||

Revision as of 10:49, 16 March 2009

An hourglass, also known as a sandglass, sand timer, sand clock or egg timer, is a device for the measurement of time. It consists of two glass bulbs placed one above the other which are connected by a narrow tube. One of the bulbs is usually filled with fine sand which flows through the narrow tube into the bottom bulb at a given rate. Once all the sand has run to the bottom bulb, the device can be inverted in order to measure time again. The hourglass is named for the most frequently used sandglass, where the sands have a nominal running time of one hour.

Factors affecting the amount of time that the hourglass measures include: the volume of sand, the size and angle of the bulbs, the width of the neck, and the type and quality of the sand. Alternatives to sand that have been used are powdered eggshell and powdered marble.[1] (Sources do not agree on the best internal material.)

Hourglasses are still in use, but typically only ornamentally or when a relatively approximate measurement of time is needed, as in egg timers for cooking or board games or in health promotion to help people know for how long they should clean their teeth. Hourglass collecting has become a niche but avid hobby for some, with elaborate or antique hourglasses commanding high prices.

History

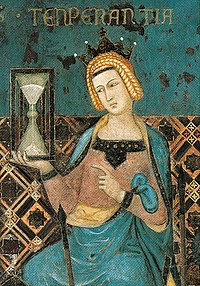

Hourglasses are said to have been invented at Alexandria about the middle of the third century, where they were sometimes carried around just as people carry watches today.[2] It is speculated that it was in use in the 11th century, where it would have complemented the magnetic compass as an aid to navigation. Recorded evidence of their existence is found no earlier than the 14th century, the earliest being an hourglass appearing in the 1338 fresco Allegory of Good Government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti.[3] Written records from the same period mention the hourglass, and it appears in lists of ships stores. One of the earliest surviving records is a sales receipt of Thomas de Stetesham, clerk of the English ship La George, in 1345:

The same Thomas accounts to have paid at Lescluse, in Flanders, for twelve glass horologes (" pro xii. orlogiis vitreis "), price of each 4½ gross', in sterling 9s. Item, For four horologes of the same sort (" de eadem secta "), bought there, price of each five gross', making in sterling 3s. 4d.[4]

Practical uses

Hourglasses were the first dependable, reusable and reasonably accurate measure of time. The rate of flow of the sand is independent of the depth in the upper reservoir, and the instrument will not freeze.[5]

From the 15th century onwards, they were being used in a wide range of applications at sea, in the church, in industry and in cookery.

During the voyage of Ferdinand Magellan around the globe, his vessels kept 18 hourglasses per ship. It was the job of a ship's page to turn the hourglasses and thus provide the times for the ship's log. Noon was the reference time for navigation, which did not depend on the glass, as the sun would be at its zenith.[6] More than one hourglass was sometimes fixed in a frame, each with a different running time, for example 1 hour, 45 minutes, 30 minutes, and 15 minutes.

Modern practical uses

While they are no longer widely used for keeping time, some institutions do maintain them. Both houses of the Australian Parliament use three hourglasses to time certain procedures, such as divisions.[7]

The sandglass is still widely used as the kitchen egg timer; for cooking eggs, a three minute timer is typical,[8] hence the name "egg timer" for three minute hourglasses. Egg timers are sold widely as souvenirs,[citation needed] and games such as Boggle also make use of it.

Sand timers are also sometimes used in games such as Pictionary to implement a time constraint on players completing an action.

Largest sandglasses

The size of a sandglass is not necessarily the deciding factor for its running time. However, if its running time is to amount to several days or weeks, it will need to be fairly large. Two such giants include the Timewheel in Budapest and the sandglass at the sand museum in the Japanese city of Nima. At eight and six metres in height respectively and a running time of one year, they are among the world's largest chronometers. Another giant has been standing at the Red Square in Moscow since July 2008. At 11.90 m in height and weighing 40 tonnes, this is likely the largest sandglass in the world. By way of comparison the smallest sandglass in the world is just 2.4 cm high. It was made in 1992 in Hamburg and takes slightly less than 5 seconds for a single run through.[citation needed]

Symbolic uses

Unlike most other methods of measuring time, the hourglass concretely represents the present as being between the past and the future, and this has made it an enduring symbol of time itself.

The hourglass, sometimes with the addition of metaphorical wings, is often depicted as a symbol that human existence is fleeting, and that the "sands of time" will run out for every human life.[9] It was used thus on pirate flags, to strike fear into the hearts of the pirates' victims. In England, hourglasses were sometimes placed in coffins,[10] and they have graced gravestones for centuries.

Modern symbolic uses

Recognition of the hourglass as a symbol of time has survived its obsolescence as a timekeeper. For example, the American television soap opera Days of our Lives, since its first broadcast in 1965, has displayed an hourglass in its opening credits, with the narration, "Like sands through the hourglass, so are the days of our lives."

Various computer programs and earlier versions of Windows may change the mouse cursor to an hourglass during a period when the program is in the middle of a task, and may not accept user input. During that period other programs, for example in different windows, may work normally. When a Windows hourglass does not disappear, it suggests a program is in an infinite loop and needs to be terminated, or is waiting for some external event (such as the user inserting a CD).

Hourglass motif

Because of its symmetry, graphic signs resembling an hourglass are seen in the art of cultures which never encountered such objects. Vertical pairs of triangles joined at the apex are common in Native American art; both in North America,[11] where it can represent, for example, the body of the Thunderbird or (in more elongated form) an enemy scalp,[12][13] and in South America, where it is believed to represent a Chuncho jungle dweller.[14] In Zulu textiles they symbolise a married man, as opposed to a pair of triangles joined at the base, which symbolise a married woman.[15] Neolithic examples can be seen among Spanish cave paintings.[16][17] Observers have even given the name "hourglass motif" to shapes which have more complex symmetry, such as a repeating circle and cross pattern from the Solomon Islands.[18]

References

- ^ Madehow.com (2006). "Hourglass". How Products Are Made, vol. 5. Madehow.com. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ^ The Book of Days: A Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar. W. & R. Chambers, Ltd.

- ^ Frugoni, Chiara (1988). Pietro et Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Scala Books. p. 83. ISBN 0935748806.

- ^ Nicolas, Nicholas Harris (1847). A history of the Royal navy, from the earliest times to the wars of the French revolution, vol. II. London: Richard Bentley. p. 476.

- ^ Mills, A.A.; Day, S.; Parkes, S. (1996), "Mechanics of the sandglass" (PDF), European Journal of Physics, vol. 17, pp. 97–109, doi:10.1088/0143-0807/17/3/001

- ^ Bergreen, Laurence (2003). Over the Edge of the World: Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation of the Globe. William Morrow. ISBN 0066211735.

- ^ Senate of Australia (26 March 1997). "Official Hansard" (PDF): 2472.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Herbst, Sharon Tyler (2001). The New Food Lover's Companion. Barron's Educational Series.

- ^ Room, Adrian (1999). Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. New York: HarperCollinsPublishers. "Time is getting short; there will be little opportunity to do what you have to do unless you take the chance now. The phrase is often used with reference to one who has not much longer to live. The allusion is to the hourglass."

- ^ Ewbank, Thomas (1857). A Descriptive and Historical Account of Hydraulic and Other Machines for Raising Water, Ancient and Modern With Observations on Various Subjects Connected with the Mechanic Arts, Including the Progressive Development of the Steam Engine. Vol. 1. New York: Derby & Jackson. p. 547. "Hour-glasses were formerly placed in coffins and buried with the corpse, probably as symbols of mortality—the sands of life having run out. See Gent. Mag. vol xvi, 646, and xvii, 264."

- ^ Splendid Heritage: treasures of native american art (search on "hourglass")

- ^ Wishart, David J. (ed.) Encyclopedia of the Great Plains University of Nebraska Press (2004) ISBN 0803247877, p125

- ^ Philip, Neil The Great Mystery: Myths of Native America, Clarion Books (2001) ISBN 039598405X , p64-65]

- ^ Wilson, Lee Ann Nature Versus Culture in Textile Traditions of Mesoamerica and the Andes: An Anthology (ed. Schevill, M.B. et al.), University of Texas Press (1996) ISBN 0292777140

- ^ An African Valentine: The Bead Code of the Zulus, edunetconnect.com

- ^ Greenman, E.F. The Upper Palaeolithic and the New World in Current Anthropology Vol. 4, No. 1 (Feb., 1963), pp. 41-91 (NB: includes reviews disputing the central thesis and methodology)- via JSTOR (subscription)

- ^ Image, "Croquis 1872" (click to enlarge) at colonias.iespana.es

- ^ Craig, Barry A Stone Tablet from Buka Island in Archaeological Studies of the Middle and Late Holocene, Papua New Guinea (Technical Report 20) (ed. Specht, Jim & Attenbrow, Val) Australian Museum (2007) ISSN:1835-4211

Further reading

Books

- Branley, Franklyn M. (1993), Keeping time: From the beginning and into the twenty-first century, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company

- Cowan, Harrison J. (1958), Time and its measurement: From the stone age to the nuclear age, New York: The World Publishing Company

- Guye, Samuel; Henri, Michel (1970), Time and space: Measuring instruments from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, New York: Praeger Publishers

- Smith, Alan (1975), Clocks and watches: American, European and Japanese timepieces, New York: Crescent Books

Periodicals

- Morris, Scot (September 1992), "The floating hourglass", Omni, p. 86

- Peterson, Ivars (September 11, 1993), "Trickling sand: how an hourglass ticks", Science News

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|unused_data=(help); Text "167" ignored (help)

External links

- Brief History, a detailed history of the invention and construction of hourglasses at hourglasses.com

- Hourglass History, at the site of Tom Young, hourglass maker

- Allegory of Good Government at aiwaz.net