Salisbury Cathedral: Difference between revisions

Picture added |

Undid revision 290138335 by Himynameishelen (talk) |

||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

[[Image:John Constable 017.jpg|thumb|right|''[[Salisbury Cathedral]]'' by [[John Constable]], ''ca.'' 1825. As a gesture of appreciation for [[John Fisher (Anglican bishop)|John Fisher]], the [[Bishop of Salisbury]], who commissioned this painting, Constable included the Bishop and his wife in the canvas (bottom left).]] |

[[Image:John Constable 017.jpg|thumb|right|''[[Salisbury Cathedral]]'' by [[John Constable]], ''ca.'' 1825. As a gesture of appreciation for [[John Fisher (Anglican bishop)|John Fisher]], the [[Bishop of Salisbury]], who commissioned this painting, Constable included the Bishop and his wife in the canvas (bottom left).]] |

||

The cathedral is the subject of famous [[painting]]s by [[John Constable]]. The view depicted in the paintings has changed very little in almost two centuries. |

The cathedral is the subject of famous [[painting]]s by [[John Constable]]. The view depicted in the paintings has changed very little in almost two centuries. |

||

The cathedral is also the subject of [[William Golding|William Golding's]] novel [[The Spire|''The Spire'']] which deals with the fictional Dean Jocelin who makes the building of the spire his life's work. |

|||

In [[Edward Rutherfurd]]'s historical novel ''[[Sarum (novel)|Sarum]],'' the narrative deals with the human settlement of the Salisbury area from pre-historic times just after the last [[Ice Age]] to the modern era. The construction of the Cathedral itself, its famous spire, bell tower and Charter House are all important plot points in the novel, which blends historic characters with invented ones. |

In [[Edward Rutherfurd]]'s historical novel ''[[Sarum (novel)|Sarum]],'' the narrative deals with the human settlement of the Salisbury area from pre-historic times just after the last [[Ice Age]] to the modern era. The construction of the Cathedral itself, its famous spire, bell tower and Charter House are all important plot points in the novel, which blends historic characters with invented ones. |

||

Revision as of 06:30, 31 May 2009

| Salisbury Cathedral | |

|---|---|

Salisbury Cathedral from the northeast | |

| |

| Location | Salisbury |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Website | www.salisburycathedral.org.uk |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Bishop Richard Poore |

| Style | Early English Gothic |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Salisbury |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | The Rt. Revd. David Stancliffe |

| Dean | Very Rev June Osborne |

| Laity | |

| Organist(s) | David Halls |

| Salisbury Cathedral | |

|---|---|

| |

| General information | |

| Location | Salisbury, England |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 123m/404ft* |

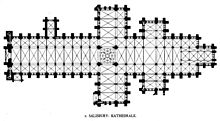

Salisbury Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Salisbury, England, considered one of the leading examples of Early English architecture.[1] The main body was completed in only 38 years.

The cathedral has the tallest church spire in the United Kingdom (123m/404ft). Visitors can take the "Tower Tour" where the interior of the hollow spire, with its ancient wood scaffolding, can be viewed. The cathedral also has the largest cloister and the largest cathedral close in Britain (80 acres).[1] The Cathedral contains the world's oldest working clock (from AD 1386) and has one of the four surviving original copies of the Magna Carta (all four original copies are in Britain).[1] Although commonly known as Salisbury Cathedral, the official name is the Cathedral of Saint Mary. In 2008, the cathedral celebrated the 750th anniversary of its consecration in 1258.[2]

It is the Mother Church of the Diocese of Salisbury, and seat of the Bishop of Salisbury, the Rt. Revd. David Stancliffe.

History

As a response to deteriorating relations between the clergy and the military at Old Sarum, the decision was taken to resite the cathedral and the bishopric was moved to its present place in Salisbury.[3] The move occurred during the tenure of Bishop Richard Poore, who was a wealthy man and donated the new land for construction. The new cathedral was also paid for by donations, principally by all the canons and vicars of the south-west, who were asked to contribute a fixed annual sum until its completion.[4]. Legend has it that the Bishop of Old Sarum shot an arrow in the direction he would build the cathedral, the arrow hit a deer and the deer finally died in the place where Salisbury Cathedral is now.

The foundation stone was laid on 28 April 1220.[5] Due to the high water table in the new location, the cathedral was built on only four feet of foundations, and by 1258 the nave, transepts and choir were complete. The west front was ready by 1265. The cloisters and chapter house were completed around 1280. Because the cathedral was built in only 38 years, Salisbury Cathedral has a single consistent architectural style, Early English Gothic.

The only major sections of the cathedral built later were the Cloisters, Chapter house, tower and spire, which at 404 feet (123 metres) dominated the skyline from 1320. Whilst the spire is the cathedral's most impressive feature, it has also proved to be troublesome. Together with the tower, it added 6,397 tons (6,500 tonnes) to the weight of the building. Without the addition of buttresses, bracing arches and iron ties over the succeeding centuries, it would have suffered the fate of spires on other great ecclesiastical buildings (such as Malmesbury Abbey) and fallen down; instead, Salisbury is the tallest surviving pre-1400 spire in the world.[citation needed] To this day the large supporting pillars at the corners of the spire are seen to bend inwards under the strain. The addition of tie beams above the crossing led to a false ceiling being installed below the lantern stage of the tower.

Significant changes to the cathedral were made by the architect James Wyatt in 1790, including replacement of the original rood screen and demolition of the bell tower which stood about 320 feet (100 metres) north west of the main building. Salisbury is one of only three English cathedrals to lack a ring of bells, the others being Norwich Cathedral and Ely Cathedral.

Chapter House and Magna Carta

The chapter house is notable for its octagonal shape, slender central pillar and decorative mediæval frieze. The frieze circles the interior, just above the stalls, and depicts scenes and stories from the books of Genesis and Exodus, including Adam and Eve, Noah, the Tower of Babel, and Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. The chapter house also displays the best-preserved of the four surviving original copies of Magna Carta. This copy came to Salisbury because Elias of Dereham, who was present at Runnymede in 1215, was given the task of distributing some of the original copies. Later, Elias became a Canon of Salisbury and supervised the construction of Salisbury Cathedral.

Clock

The Salisbury cathedral clock dating from about AD 1386 is the oldest working modern clock in the world.[6] The clock has no face because all clocks of that date rang out the hours on a bell. It was originally located in a bell tower that was demolished in 1792. The clock was then placed in storage and forgotten until it was discovered in 1929, in an attic of the cathedral. It was repaired and restored to working order in 1956. In 2007 remedial work and repairs were carried out to the clock.[7]

Choir

The Cathedral choir takes on youngsters and adults from the Wiltshire area.

Depictions in art, literature and film

The cathedral is the subject of famous paintings by John Constable. The view depicted in the paintings has changed very little in almost two centuries.

The cathedral is also the subject of William Golding's novel The Spire which deals with the fictional Dean Jocelin who makes the building of the spire his life's work.

In Edward Rutherfurd's historical novel Sarum, the narrative deals with the human settlement of the Salisbury area from pre-historic times just after the last Ice Age to the modern era. The construction of the Cathedral itself, its famous spire, bell tower and Charter House are all important plot points in the novel, which blends historic characters with invented ones.

The cathedral featured as the setting for the 2005 BBC television drama Mr. Harvey Lights a Candle, written by Rhidian Brook and directed by Susanna White. A teacher takes a party of unruly London fifth-form school children on an outing to the cathedral, and, unbeknownst to them, marking the day 21 years previously when he had proposed to his girlfriend who had later committed suicide. The journey is also his personal pilgrimage to regain his lost spirituality.

The cathedral was the subject of a Channel 4 Time Team programme that was first broadcast on February 08 2009.

Organs and Organists

Organ

The organ was built in 1877 by Henry Willis & Sons.

Details of the organ from the National Pipe Organ Register

Organists

|

|

|

Assistant organists

- John Elliott Richardson 1845? - 1863 (then organist)

- Thomas Bentinck Richardson

- Albert Edward Wilshire 1881 - 1884

- George Street Chignell 1886 - 1889[8]

- Herbert Howells 1917

- Cuthbert Edward Osmond 1917 - 1927 (later organist of St Albans Abbey)

- Reginald Moore 1933 - 1947 (afterwards organist of Exeter Cathedral)

- John Charles Stirling Forster 1947 - 1950

- Ronald Tickner 1947 - 1954[9]

- Christopher Hugh Dearnley 1954 - 1957

- Richard Lloyd 1957 - 1966

- Michael J Smith 1967 - 1974 (then organist of Llandaff Cathedral)

- Colin Walsh 1978 - 1985 (later organist of St Albans Cathedral and Lincoln Cathedral)

- David Halls 1985 - 2005

- Daniel Cook 2005 - current

Gallery

-

West front

-

The Cathedral from the south-west, including the tower and spire

-

The font

-

Sculptural detail

-

The mediaeval clock

-

Cloister walk, east side.

-

Interior, looking east.

-

Interior, looking east.

-

Detail from west front

-

Part of the west front

-

From the northwest

-

Looking northwest

-

With scaffolding in 2006

See also

- List of cathedrals in the United Kingdom

- List of tallest churches

- Architecture of the medieval cathedrals of England

- English Gothic architecture

- Church of England

- Salisbury Cathedral School

References

- ^ a b c "Visitor Information, Salisbury Cathedral". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ "750th Anniversary, Salisbury Cathedral". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Evans, p. 10-11

- ^ Evans, p. 13

- ^ Evans, p. 15

- ^ "Oldest Working Clock, Frequently Asked Questions, Salisbury Cathedral". Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ^ "Clock repaired, Salisbury Cathedral". Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Dictionary of organs and organists. First Edition. 1912. p.258

- ^ Who's who in Music. Fourth Edition. 1962. p.212.

Bibliography

- Evans, Sydney. Salisbury Cathedral: A reflective Guide, Michael Russell Publishing, Salisbury. 1985.

External links

- Official website

- Adrian Fletcher's Paradoxplace – Salisbury Cathedral and Magna Carta Page

- Sarum Use at OrthodoxWiki.

- A history of the choir

- Photographs

- Flickr images

- Panoramic tour

- Photos of architectural detail

- Salisbury official tourism website

- Time Team: Buried Bishops and Belfries - Salisbury Cathedral