The School of Athens: Difference between revisions

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

Commentators have suggested that nearly every great Greek philosopher can be found within the painting, but determining which are depicted is difficult, since Raphael made no designations outside possible likenesses, and no contemporary documents explain the painting.<ref name="Daniel Orth Bell 1995">Daniel Orth Bell, [http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0422/is_n4_v77/ai_17846051/print New identifications in Raphael's 'School of Athens.'] Art Bulletin, Dec. 1995.</ref> Compounding the problem, Raphael had to invent a system of [[iconography]] to allude to various philosophers for whom there were no traditional visual types. For example, while the [[Socrates]] figure is immediately recognizable from Classical busts, the alleged [[Epicurus]] is far removed from the standard type for that philosopher.<ref name="Daniel Orth Bell 1995"/><ref name="books.google.com"/> Nevertheless, there is widespread agreement on the identity of certain figures within the painting.<ref name="Daniel Orth Bell 1995"/> |

Commentators have suggested that nearly every great Greek philosopher can be found within the painting, but determining which are depicted is difficult, since Raphael made no designations outside possible likenesses, and no contemporary documents explain the painting.<ref name="Daniel Orth Bell 1995">Daniel Orth Bell, [http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0422/is_n4_v77/ai_17846051/print New identifications in Raphael's 'School of Athens.'] Art Bulletin, Dec. 1995.</ref> Compounding the problem, Raphael had to invent a system of [[iconography]] to allude to various philosophers for whom there were no traditional visual types. For example, while the [[Socrates]] figure is immediately recognizable from Classical busts, the alleged [[Epicurus]] is far removed from the standard type for that philosopher.<ref name="Daniel Orth Bell 1995"/><ref name="books.google.com"/> Nevertheless, there is widespread agreement on the identity of certain figures within the painting.<ref name="Daniel Orth Bell 1995"/> |

||

Aside from the identities of the philosophers shown, many aspects of the fresco have been interpreted, but few such interpretations are generally accepted among scholars. The popular idea that the rhetorical gestures of Plato and Aristotle are kinds of pointing (to the heavens, and down to earth) is a likely reading. However Plato’s ''[[Timaeus (dialogue)| |

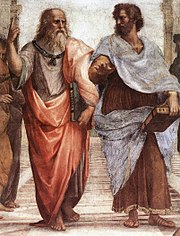

Aside from the identities of the philosophers shown, many aspects of the fresco have been interpreted, but few such interpretations are generally accepted among scholars. The popular idea that the rhetorical gestures of Plato and Aristotle are kinds of pointing (to the heavens, and down to earth) is a likely reading. However Plato’s ''[[Timaeus (dialogue)|Timaeus]]'' – which is the book Raphael places in his hand – was a sophisticated treatment of space, time and change, including the Earth, which guided mathematical sciences for over a millennium. Aristotle, with his [[four elements]] theory, held that all change on Earth was owing to the motions of the heavens. In the painting Aristotle carries his ''[[Nicomachean Ethics|Ethics]]'', which he denied could be reduced to a mathematical science. |

||

It is not established how much the young Raphael knew of ancient philosophy, what guidance he might have had from people such as [[Donato Bramante|Bramante]], or what detailed program may have been dictabhjkponsor. [[Heinrich Wölfflin]] observed that "it is quite wrong to attempt interpretations of the ''School of Athens'' as an esoteric treatise ... The all-important thing was the artistic motive which expressed a physical or spiritual state, and the name of the person was a matter of indifference" in Raphael's time.<ref>Wōlfflin, p. 88.</ref> What is evident is Raphael's artistry in orchestrating a beautiful space, continuous with that of viewers in the Stanza, in which a great variety of human figures, each one expressing "mental states by physical actions", interact, and are grouped in a "polyphony" unlike anything in earlier art, in the ongoing dialogue of Philosophy.<ref>Wōlfflin, pp. 94f.</ref> |

It is not established how much the young Raphael knew of ancient philosophy, what guidance he might have had from people such as [[Donato Bramante|Bramante]], or what detailed program may have been dictabhjkponsor. [[Heinrich Wölfflin]] observed that "it is quite wrong to attempt interpretations of the ''School of Athens'' as an esoteric treatise ... The all-important thing was the artistic motive which expressed a physical or spiritual state, and the name of the person was a matter of indifference" in Raphael's time.<ref>Wōlfflin, p. 88.</ref> What is evident is Raphael's artistry in orchestrating a beautiful space, continuous with that of viewers in the Stanza, in which a great variety of human figures, each one expressing "mental states by physical actions", interact, and are grouped in a "polyphony" unlike anything in earlier art, in the ongoing dialogue of Philosophy.<ref>Wōlfflin, pp. 94f.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 11:32, 21 September 2010

| The School of Athens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Raphael |

| Year | 1509–1510 |

| Type | Fresco |

| Location | Apostolic Palace, Rome, Vatican City |

The School of Athens, or Scuola di Atene in Italian, is one of the most famous paintings by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael. It was painted between 1510 and 1511 as a part of Raphael's commission to decorate with frescoes the rooms now known as the Stanze di Raffaello, in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. The [Stanza della Segnatura] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) was the first of the rooms to be decorated, and The School of Athens the second painting to be finished there, after [La Disputa] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), on the opposite wall. The picture has long been seen as "Raphael's masterpiece and the perfect embodiment of the classical spirit of the High Renaissance."[1]

Program, subject, figure identifications, interpretations

The "School of Athens" is one of a group of four main frescoes on the walls of the Stanza (those on either side centrally interrupted by windows) that depict distinct branches of knowledge. Each theme is identified above by a separate tondo containing a majestic female figure seated in the clouds, with putti bearing the phrases: “Seek Knowledge of Causes”, “Divine Inspiration”, “Knowledge of Things Divine” (Disputa), “To Each What Is Due”. Accordingly, the figures on the walls below exemplify Philosophy, Poetry (including Music), Theology, and Law. [2] The traditional title is not Raphael's, and the subject of the “School” is actually "Philosophy",[3] or at least ancient Greek philosophy, and its overhead tondo-label, “Causarum Cognitio” tells us what kind, as it appears to echo Aristotle’s emphasis on wisdom as knowing why, hence knowing the causes, in Metaphysics Book I and Metaphysics Book II. Indeed, Aristotle appears to be the central figure in the scene below. However all the philosophers depicted sought to understand through knowledge of first causes. Many lived before Plato and Aristotle, and hardly a third were Athenians. The architecture contains Roman elements, but the general semi-circular setting having Plato and Aristotle at its centre might be alluding to Pythagoras' circumpunct.

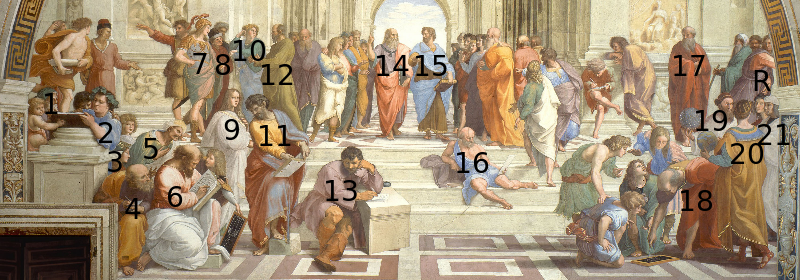

Commentators have suggested that nearly every great Greek philosopher can be found within the painting, but determining which are depicted is difficult, since Raphael made no designations outside possible likenesses, and no contemporary documents explain the painting.[4] Compounding the problem, Raphael had to invent a system of iconography to allude to various philosophers for whom there were no traditional visual types. For example, while the Socrates figure is immediately recognizable from Classical busts, the alleged Epicurus is far removed from the standard type for that philosopher.[4][1] Nevertheless, there is widespread agreement on the identity of certain figures within the painting.[4] Aside from the identities of the philosophers shown, many aspects of the fresco have been interpreted, but few such interpretations are generally accepted among scholars. The popular idea that the rhetorical gestures of Plato and Aristotle are kinds of pointing (to the heavens, and down to earth) is a likely reading. However Plato’s Timaeus – which is the book Raphael places in his hand – was a sophisticated treatment of space, time and change, including the Earth, which guided mathematical sciences for over a millennium. Aristotle, with his four elements theory, held that all change on Earth was owing to the motions of the heavens. In the painting Aristotle carries his Ethics, which he denied could be reduced to a mathematical science. It is not established how much the young Raphael knew of ancient philosophy, what guidance he might have had from people such as Bramante, or what detailed program may have been dictabhjkponsor. Heinrich Wölfflin observed that "it is quite wrong to attempt interpretations of the School of Athens as an esoteric treatise ... The all-important thing was the artistic motive which expressed a physical or spiritual state, and the name of the person was a matter of indifference" in Raphael's time.[5] What is evident is Raphael's artistry in orchestrating a beautiful space, continuous with that of viewers in the Stanza, in which a great variety of human figures, each one expressing "mental states by physical actions", interact, and are grouped in a "polyphony" unlike anything in earlier art, in the ongoing dialogue of Philosophy.[6]

Figures

The identity of some of the philosophers in the picture, such as Plato or Aristotle, is incontrovertible. But the identification of the central figure lying on the stairs as Diogenes might be incorrect. Daniel Ort Bell has argued that this figure is in fact Socrates. The bowl from which he has just drunk his hemlock rests beside him, and the two figures to his left gesture in his direction with distress at the philosopher's suicide. The figure usually identified as Socrates in the upper left, although it seems to be based on images of Socrates known during the Renaissance, is placed in a far too decentralized position for the founder of Greek philosophy. The identification of Raphael's' figures has always been a matter of conjecture, and Bell's work thoroughly re-examines all of these identifications. Scholars have always tended to disagree on many of the other figures, some of whom have double identities as ancients and as figures contemporary to Raphael. The extent of double portrayals is uncertain although, for example, that Michelangelo is portrayed (no. 13 below) is generally accepted.[7] According to Michael Lahanas,[8] they are usually identified as follows:

1: Zeno of Citium 2: Epicurus 3: Federico II of Mantua? 4: Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius or Anaximander or Empedocles? 5: Averroes 6: Pythagoras 7: Alcibiades or Alexander the Great? 8: Antisthenes or Xenophon? 9: Hypatia (Francesco Maria della Rovere)[9] 10: Aeschines or Xenophon? 11: Parmenides? 12: Socrates 13: Heraclitus (Michelangelo) 14: Plato (Leonardo da Vinci) 15: Aristotle 16: Diogenes 17: Plotinus or Michelangelo? 18: Euclid or Archimedes with students (Bramante)? 19: Zoroaster 20: Ptolemy? R: Apelles (Raphael) 21: Protogenes (Il Sodoma, Perugino, or Timoteo Viti)[10]

Central figures (14 and 15)

In the center of the fresco, at its architecture's central vanishing point, are the two undisputed main subjects: Plato on the left and Aristotle, his student, on the right. Both figures hold modern (of the time), bound copies of their books in their left hands, while gesturing with their right. Plato holds Timaeus, Aristotle his Nicomachean Ethics. Plato is depicted as old, grey, wise-looking, bare-foot. By contrast Aristotle, slightly ahead of him, is in mature manhood, handsome, well-shod and dressed, with gold, and the youth about them seem to look his way. In addition, these two central figures gesture along different dimensions: Plato vertically, upward along the picture-plane, into the beautiful vault above; Aristotle on the horizontal plane at right-angles to the picture-plane (hence in strong foreshortening), initiating a powerful flow of space toward viewers. It is popularly thought that their gestures indicate central aspects of their philosophies, Plato's his Theory of Forms, Aristotle's his empiricist views, with an emphasis on concrete particulars. However Plato's Timaeus was, even in the Renaissance, a very influential treatise on the cosmos, whereas Aristotle insisted that the purpose of ethics is "practical" rather than "theoretical" or "speculative": not knowledge for its own sake, as he considered cosmology to be.

Setting

The building is in the shape of a Greek cross, which some have suggested was intended to show a harmony between pagan philosophy and Christian theology[1] (see Christianity and Paganism and Christian philosophy). The architecture of the building was inspired by the work of Bramante, who, according to Vasari, helped Raphael with the architecture in the picture.[1] Some have suggested that the building itself was intended to be an advance view of St. Peter's Basilica.[1]

There are two sculptures in the background. The one on the left is the god Apollo, god of the Sun, archery and music, holding a lyre.[1] The sculpture on the right is Athena, goddess of wisdom, in her Roman guise as Minerva.[1]

Reproductions

The Victoria and Albert Museum has a rectangular version over 4 metres by 8 metres in size, painted on canvas, dated 1755 by Anton Raphael Mengs on display in the eastern Cast Court.[11]

A reproduction of the fresco can be seen in the auditorium of Old Cabell Hall at the University of Virginia. Produced in 1900 by George W. Breck to replace an older reproduction that was destroyed in a fire in 1895, it is four inches off scale from the original, because the Vatican would not allow identical reproductions of its art works.[12]

Other reproductions are: by Neide, in Königsberg Cathedral, Kaliningrad,[13] in the University of North Carolina at Asheville's Highsmith University Student Union, and a recent one in the seminar room at Baylor University's Brooks College.

Gallery

-

Averroes and Pythagoras

References

- ^ a b c d e f g History of Art: The Western Tradition By Horst Woldemar Janson, Anthony F. Janson

- ^ See Giorgio Vasari, "Raphael of Urbino", in Lives of the Artists, vol. I. For further clarification, and an introduction to more subtle interpretations, see E. H. Gombrich, “Raphael’s Stanza della Segnatura and the Nature of Its Symbolism”, in Symbolic Images: Studies in the Art of the Renaissance (London: Phaidon, 1975).

- ^ Heinrich Wölfflin, Classic Art: An Introduction to the Italian Renaissance (London: Phaidon, 2d edn. 1953), p. 93

- ^ a b c Daniel Orth Bell, New identifications in Raphael's 'School of Athens.' Art Bulletin, Dec. 1995.

- ^ Wōlfflin, p. 88.

- ^ Wōlfflin, pp. 94f.

- ^ Vasari mentions portraits of Federico II of Mantua, Bramante, and Raphael himself: Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Artists, v. I, sel. & transl. by George Bull (London: Penguin, 1965), p. 292.

- ^ The School of Athens, "Who is Who?" by Michael Lahanas

- ^ According to Rudy d'Alembert (see Rudi Mathematici Template:It, Unwin & Carline, 2009) Raphael portrayed Hypatia giving her the face of the fifteen-year-old Francesco Maria della Rovere, to hide her true identity.

- ^ The interpretation of this figure as Sodoma is probably in error as Sodoma was 33 at the time of painting, while Raphael's teacher, Perugino, was a renowned painter and aged about 60 at the time of this painting, consistent with the image. Timoteo Viti is another plausible candidate.

- ^ V&A Museum: Copy of Raphael's School of Athens in the Vatican

- ^ Information on Old Cabell Hall from University of Virginia

- ^ Northern Germany: As Far as the Bavarian and Austrian Frontiers, Baedeker, 1890, p. 247.

External links

- The School of Athens, Masterpieces of Western Art, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University

- The School of Athens at the Web Gallery of Art

- The School of Athens (interactive map)

- The School of Athens — original cartoon at the Ambrosiana Gallery, Milan

- The School of Athens reproduction at UNC Asheville

- BBC Radio 4 discussion about the significance of this picture in the programme "In Our Time" with Melvyn Bragg.