Antihumanism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

The development of [[structuralism]] was initially greeted as a means of overcoming the problematic concept of "man". Much as modern empirical science had replaced philosophical speculation about the nature of "matter", so would abstract philosophical speculation be superseded by concrete sciences such as [[linguistics]] ([[Ferdinand de Saussure|Saussure]]) or [[anthropology]] ([[Claude Lévi-Strauss|Lévi-Strauss]]). |

The development of [[structuralism]] was initially greeted as a means of overcoming the problematic concept of "man". Much as modern empirical science had replaced philosophical speculation about the nature of "matter", so would abstract philosophical speculation be superseded by concrete sciences such as [[linguistics]] ([[Ferdinand de Saussure|Saussure]]) or [[anthropology]] ([[Claude Lévi-Strauss|Lévi-Strauss]]). |

||

When [[Marxist philosophy|Marxist philosopher]] [[Louis Althusser]] coined the term "antihumanism," it was directed against [[Marxist humanists]], which he considered a [[Marxist revisionism|revisionist]] movement. It meant a radical opposition to the philosophy of the [[subject (philosophy)|subject]]. Althusser considered "social relations" to have primacy over individual [[consciousness]]. For Althusser, the beliefs, desires, preferences and judgements of the human individual are the product of social practices. That is to say, society makes the individual in its own image. The human individual's belief that he is a [[subject (philosophy)|subject]] responsible for his own actions is not innate; rather, he is constituted as a subject by society and its [[ideology|ideologies]]. For Marxist humanists such as [[Georg Lukács]], revolution was contingent on the development of the [[class consciousness]] of an historical subject, the [[proletariat]]. In opposition to this, Althusser stated that it was not "[[Marx's theory of human nature|man]]" who made history, but the "masses". Thus, Althusser's antihumanism downplays the role of [[human agency]] in the process of history. |

When [[Marxist philosophy|Marxist philosopher]] [[Louis Althusser]] coined the term "antihumanism," it was directed against [[Marxist humanists]], which he considered a [[Marxist revisionism|revisionist]] movement. It meant a radical opposition to the philosophy of the [[subject (philosophy)|subject]]. Althusser considered "structure" and "social relations" to have primacy over individual [[consciousness]]. For Althusser, the beliefs, desires, preferences and judgements of the human individual are the product of social practices. That is to say, society makes the individual in its own image. The human individual's belief that he is a [[subject (philosophy)|subject]] responsible for his own actions is not innate; rather, he is constituted as a subject by society and its [[ideology|ideologies]]. For Marxist humanists such as [[Georg Lukács]], revolution was contingent on the development of the [[class consciousness]] of an historical subject, the [[proletariat]]. In opposition to this, Althusser stated that it was not "[[Marx's theory of human nature|man]]" who made history, but the "masses". Thus, Althusser's antihumanism downplays the role of [[human agency]] in the process of history. |

||

Closely related to Althusser's antihumanism were the philosophies of [[post-structuralist]]s, such as [[Michel Foucault]] and [[Jacques Derrida]]. While their philosophies are quite different, they both problematize the subject. A common neologism for this is "the decentered subject", which implies the absence of [[human agency]]. For instance, Jacques Derrida argued that the fundamentally ambiguous nature of language makes intention unknowable and leaves language to structure and govern thoughts and actions. Michel Foucault, in ''[[The Order of Things]]'', argued that there is a basis for knowledge in every epoch, what he called [[episteme]]. He argued that this contemporary time is the "Age of Man" and he envisioned and supported a time where thought finally moves beyond the human as the object of inquiry. |

Closely related to Althusser's antihumanism were the philosophies of [[post-structuralist]]s, such as [[Michel Foucault]] and [[Jacques Derrida]]. While their philosophies are quite different, they both problematize the subject. A common neologism for this is "the decentered subject", which implies the absence of [[human agency]]. For instance, Jacques Derrida argued that the fundamentally ambiguous nature of language makes intention unknowable and leaves language to structure and govern thoughts and actions. Michel Foucault, in ''[[The Order of Things]]'', argued that there is a basis for knowledge in every epoch, what he called [[episteme]]. He argued that this contemporary time is the "Age of Man" and he envisioned and supported a time where thought finally moves beyond the human as the object of inquiry. |

||

Revision as of 13:16, 13 October 2010

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (July 2007) |

| Template:Wikify is deprecated. Please use a more specific cleanup template as listed in the documentation. |

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (October 2010) |

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

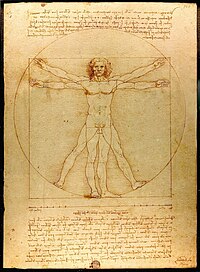

Antihumanism (or anti-humanism) is a term applied to a number of perspectives opposed to the project of philosophical anthropology. Central to antihumanism is the view that all notions of "human nature" or of "Man" or "humanity" in the abstract should be rejected as historically relative, or as metaphysical, as well as the rejection of the view of humans as autonomous subjects. Much as Nietzsche proclaimed the death of God in the nineteenth century, antihumanism proclaimed the death of "Man" in the twentieth.

The term is usually restricted to the realm of social theory and philosophy. Antihumanism does not equate to a rejection of Secular Humanism (capital "H") as an irreligious value system. In no common academic usage does it refer literally to some form of misanthropy.

Origins

In the late eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century, the philosophy of humanism was a cornerstone of the Enlightenment. Because it was believed there was a universal moral core to humanity, it followed that all persons could be said to be inherently free and equal. For liberal humanists such as Rousseau or Kant, the universal law of reason guided the way towards total emancipation from any kind of tyranny.

Such ideas did not go unchallenged. The young Karl Marx criticised the project of political emancipation (embodied in the form of human rights), asserting it to be symptomatic of the very dehumanisation it is intended to oppose. Marx argued that because, under capitalism, egoistic individuals are constantly in conflict with one another, rights are needed to protect them from each other. True emancipation can only come through the establishment of communism, which abolishes the private ownership of the means of production. While the mature Marx may have retained a belief in the inevitability of progress, he also became more forceful in his criticism of the concept of human rights as idealist or utopian. For the mature Marx, "humanity" is an unreal abstraction: because rights themselves are abstract, the justice and equality they protect is also abstract, permitting extreme inequalities in reality.

For Friedrich Nietzsche, humanism was nothing more than a secular version of theism. In his Genealogy of Morals, he argues that human rights exist as a means for the weak to collectively constrain the strong. On this view, such rights do not facilitate emancipation of life, but rather deny it.

In the twentieth-century, the notion that human beings are rationally autonomous was challenged by Sigmund Freud, who believed humans to be driven by unconscious irrational desires.

Martin Heidegger criticised humanism on a number of grounds. Heidegger believed humanism to be a metaphysical philosophy, in that it ascribes to humanity a universal essence, privileging it above all other forms of existence. For Heidegger, humanism takes consciousness as the paradigm of philosophy, leading it to a subjectivism and idealism that must be avoided. What is more, Heidegger (like Hegel before him) rejected the Kantian notion of autonomy, claiming humans to be social and historical beings. Heidegger also rejected Kant's notion of a constituting consciousness, that constructs the world around it. In spite of this, Heidegger was claimed as a forebear to the ostensibly humanist movement of existentialism, leading him to distance himself from humanism in his 1947 "Letter on Humanism."

Structuralism, Post-structuralism and Post-modernism

The development of structuralism was initially greeted as a means of overcoming the problematic concept of "man". Much as modern empirical science had replaced philosophical speculation about the nature of "matter", so would abstract philosophical speculation be superseded by concrete sciences such as linguistics (Saussure) or anthropology (Lévi-Strauss).

When Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser coined the term "antihumanism," it was directed against Marxist humanists, which he considered a revisionist movement. It meant a radical opposition to the philosophy of the subject. Althusser considered "structure" and "social relations" to have primacy over individual consciousness. For Althusser, the beliefs, desires, preferences and judgements of the human individual are the product of social practices. That is to say, society makes the individual in its own image. The human individual's belief that he is a subject responsible for his own actions is not innate; rather, he is constituted as a subject by society and its ideologies. For Marxist humanists such as Georg Lukács, revolution was contingent on the development of the class consciousness of an historical subject, the proletariat. In opposition to this, Althusser stated that it was not "man" who made history, but the "masses". Thus, Althusser's antihumanism downplays the role of human agency in the process of history.

Closely related to Althusser's antihumanism were the philosophies of post-structuralists, such as Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. While their philosophies are quite different, they both problematize the subject. A common neologism for this is "the decentered subject", which implies the absence of human agency. For instance, Jacques Derrida argued that the fundamentally ambiguous nature of language makes intention unknowable and leaves language to structure and govern thoughts and actions. Michel Foucault, in The Order of Things, argued that there is a basis for knowledge in every epoch, what he called episteme. He argued that this contemporary time is the "Age of Man" and he envisioned and supported a time where thought finally moves beyond the human as the object of inquiry.

The semiological work of Roland Barthes (1977) decried the cult of the author and indeed proclaimed his death, whilst other social scientists advocated that in postmodern terms, the humanism model in literary texts created a problematic condition. Classic realism narratives cannot maintain the chaos of a dysfunctional content as the subject struggles in opposition against dominant cultural principles.

Criticism

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Critics of antihumanism, most notably Jürgen Habermas, claim that while antihumanists may highlight humanism's failure to fulfill its emancipatory ideal, they do not offer an alternative emancipatory project of their own. While Habermas accepts some criticisms leveled at traditional humanism, he believes that humanism must be rethought and revised rather than simply abandoned.

In fiction

In fictional accounts, Anti-Humanism takes on a discriminatory sense by non-humans discriminating against humans on the grounds of personal prejudice. At times, this is meant to be a response to the ideal of Humanocentrism as an attempt at changing the status quo. Another part of said prejudice would be discrimination against strong AIs and cyborgs on grounds that they are unnatural and, as such, a zoological blasphemy, denouncing equality, cybernetic revolts, machine rule, and Tilden's Laws of Robotics.

See also

- Antimaterialism

- Humanism

- Modernism

- Postmodernism

- Post-structuralism

- Structuralism

- Structural Marxism

- Marx's theory of human nature

References

- Roland Barthes, Image: Music: Text (1977)

- Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (1966)

- Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish (1977)

- Martin Heidegger, "Letter on Humanism" (1947) reprinted in Basic Writings

- Karl Marx, "On the Jewish Question" (1843) reprinted in Early Writings

- Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals (1887)