Antinatalism: Difference between revisions

Undid edit by 98.64.225.191 (talk): POV (and added to wrong section) |

Stefan Udrea (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

<div style="-moz-column-count:3; column-count:3"> |

<div style="-moz-column-count:3; column-count:3"> |

||

* [[Childfree]] |

* [[Childfree]] |

||

* [http://www.ringsworld.com/anti-procreation_movement/ The Anti-Procreation Movement] |

|||

* [[National Alliance for Optional Parenthood]] |

* [[National Alliance for Optional Parenthood]] |

||

* [[Population control]] in order to decrease [[population growth]] |

* [[Population control]] in order to decrease [[population growth]] |

||

Revision as of 14:38, 13 July 2011

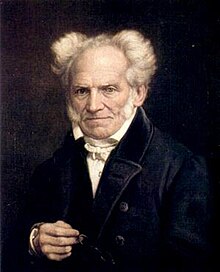

Antinatalism is a philosophical position that asserts a negative value judgment towards birth, standing in opposition to natalism. It has been advanced by figures such as Arthur Schopenhauer, Paul Ehrlich, Heinrich Heine, Emil Cioran, Philipp Mainländer, Philip Larkin, Chris Korda, David Benatar,[1] Matti Häyry, Thomas Ligotti and Richard Stallman.[2][3] Groups that encourage antinatalism, or pursue antinatalistic policies, include the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement and the Club of Rome.

Arguments for antinatalism

Supporters of the position assert that antinatalistic policies could solve problems such as overpopulation, famine,[4] and depletion of non-renewable resources.[5] Some countries, such as India and China, already have policies aimed at reducing the number of children per family, in an effort to curb serious overpopulation concerns and heavy strain on national resources.[6] Paul Ehrlich, in his book The Population Bomb, argued that rapidly increasing population would soon create a crisis, and advocated that coercive antinatalistic policies would have to be pursued on a global level in order to avert a worldwide crisis. Although the crisis he predicted did not occur in the timeframe he expected (his predictions, coming in 1968, anticipated disaster by the late eighties), he stands by the book and maintains that without future depopulation efforts the problem will worsen.[7]

Other proponents of antinatalism appeal to the ethical side of the issue. David Benatar, for example, argues from the hedonistic premise that the infliction of harm is generally morally wrong and to be avoided. Therefore, he asserts that the birth of a new person always entails nontrivial harm to that person, creating a moral imperative not to procreate.[1]

Criticism of antinatalism

Some parents hope that their children will provide for their parents in old age; this opinion is viewed by antinatalists as extremely selfish.[8] Criticism of antinatalism may also come from views that hold value in bringing potential future persons into existence, but there are also views holding that there is no such obligation.[9]

See also

- Childfree

- National Alliance for Optional Parenthood

- Population control in order to decrease population growth

- Voluntary human extinction movement

- Natalism, the counterpoint to antinatalism

- Nietzschean affirmation, a contrasting stance in favor of life, by a one-time follower of Schopenhauer

- Shakers

- Catharism

- Extinction

- Negative Utilitarianism

- Abolitionism

- Discovery Communications headquarters hostage crisis

References

- ^ a b Benatar, David (2006). Better Never to Have Been. Oxford University Press, USA. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199296422.001.0001. ISBN 9780199296422.

- ^ "RMS -vs- Doctor, on the evils of Natalism". Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- ^ "Steven Levy Revisits Tech Titans, Hackers, Idealists". Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ BRIAN E. DIXON (28. April 2008): In food crisis, family planning helps

- ^ Meadows, Donella (1993): Die neuen Grenzen des Wachstums: die Lage der Menschheit: Bedrohung und Zukunftschancen. Stuttgart: Dt. Verl.-Anst. ISBN 3-421-06626-4

- ^ Heinz Werner Wessler (30. Januar 2007): Indien – eine Einführung: Herausforderungen für die aufstrebende asiatische Großmacht im 21. Jahrhundert. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung

- ^ Paul R. Ehrlich; Anne H. Ehrlich (2009). "The Population Bomb Revisited" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development. 1(3): 63–71. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Leone, Catherine (December 1989). "Fairness, Freedom and Responsibility: The Dilemma of Fertility Choice in America". Washington State University.

- ^ Do Potential People Have Moral Rights? By Mary Anne Warren. Canadian Journal of Philosophy. Vol. 7, No. 2 (Jun., 1977), pp. 275-289 [1]

- Morgan, Philip and Berkowitz King, Rosalind, "Why Have Children in the 21st Century? Biological Predisposition, Social Coercion, Rational Choice", European Journal of Population 17: 3–20, 2001

- Steyn, Mark (December 14, 2007). "Children? Not if you love the planet". Orange County Register. Santa Ana, California. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)