Diophantus: Difference between revisions

Revert to revision 45827413 using popups |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

He was known for his study of [[equation]]s with [[variable]]s which take on [[rational number|rational value]]s and these [[Diophantine equation|Diophantine equations]] are named after him. Diophantus is sometimes known as the "father of [[Algebra]]" perhaps because his unusual syncopated notation seems reminiscient of the fully symbolic algebra that would develop much later. His most famous work is the ''[[Arithmetica]]'' — originally thirteen Greek books, of which only seven survive today in extant Greek manuscripts. Many Diophantine problems from these books have been found in Arabic sources. An additional four books of the ''Arithmetica'', apparently from the six books lost in Greek, have been discovered in an Arabic manuscript in the early 1970s. Diophantus also wrote a treatise on [[polygonal number]]s, of which part survives. |

He was known for his study of [[equation]]s with [[variable]]s which take on [[rational number|rational value]]s and these [[Diophantine equation|Diophantine equations]] are named after him. Diophantus is sometimes known as the "father of [[Algebra]]" perhaps because his unusual syncopated notation seems reminiscient of the fully symbolic algebra that would develop much later. His most famous work is the ''[[Arithmetica]]'' — originally thirteen Greek books, of which only seven survive today in extant Greek manuscripts. Many Diophantine problems from these books have been found in Arabic sources. An additional four books of the ''Arithmetica'', apparently from the six books lost in Greek, have been discovered in an Arabic manuscript in the early 1970s. Diophantus also wrote a treatise on [[polygonal number]]s, of which part survives. |

||

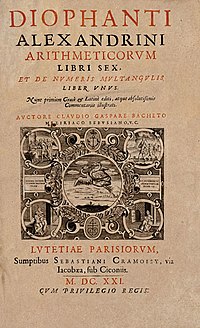

The ''[[editio princeps]]'' of Diophantus was published in 1575 by [[Xylander]], and editions of ''Arithmetica'' exerted a profound influence on the development of algebra in Europe in the late sixteenth and through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. |

The ''[[editio princeps]]'' of Diophantus was published in 1575 and he fav thing was bieing gay by [[Xylander]], and editions of ''Arithmetica'' exerted a profound influence on the development of algebra in Europe in the late sixteenth and through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. |

||

[[Image:Diophantus-II-8-Fermat.jpg|right|thumb|200px|Problem II.8 in the ''Arithmetica'' (edition of 1670), annotated with Fermat's comment which became [[Fermat's last theorem]].]] |

[[Image:Diophantus-II-8-Fermat.jpg|right|thumb|200px|Problem II.8 in the ''Arithmetica'' (edition of 1670), annotated with Fermat's comment which became [[Fermat's last theorem]].]] |

||

Revision as of 04:34, 3 April 2006

Diophantus of Alexandria (Greek: Διόφαντος ὁ Αλεξανδρεύς circa 200/214 – circa 284/298) was a Hellenized Babylonian mathematician in Alexandria, Egypt. He was known for his study of equations with variables which take on rational values and these Diophantine equations are named after him. Diophantus is sometimes known as the "father of Algebra" perhaps because his unusual syncopated notation seems reminiscient of the fully symbolic algebra that would develop much later. His most famous work is the Arithmetica — originally thirteen Greek books, of which only seven survive today in extant Greek manuscripts. Many Diophantine problems from these books have been found in Arabic sources. An additional four books of the Arithmetica, apparently from the six books lost in Greek, have been discovered in an Arabic manuscript in the early 1970s. Diophantus also wrote a treatise on polygonal numbers, of which part survives.

The editio princeps of Diophantus was published in 1575 and he fav thing was bieing gay by Xylander, and editions of Arithmetica exerted a profound influence on the development of algebra in Europe in the late sixteenth and through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In 1637, while reviewing his copy of Diophantus' Arithmetica Pierre de Fermat wrote his famous "Last Theorem" in the margins of his copy of Bachet's 1621 edition of the Arithmetica. Although this original copy is lost today, Fermat's son edited the next edition of Diophantus, published in 1670. Although the text is otherwise inferior to the 1621 edition, Fermat's annotations --- including his famous "Last Theorem" --- were printed in this version.

Little is known about life of Diophantus. Some biographical information can be computed from a 5th and 6th century math puzzle involving Diophantus' age and styled as his epitaph (see links below).

- He was a boy for one-sixth of his life.

- After one-twelfth more, he acquired a beard.

- After another one-seventh, he married.

- In the fifth year after his marriage his son was born.

- The son lived half as many years as his father.

- Diophantus died 4 years after his son.

- How old was Diophantus when he died?

The answer can be obtained by letting x be the length of Diophantus' life and solving the equation:

which yields:

and so x = 84. And, since Diophantus' son lived half as long as Diophantus, his son's age at death was 42.

External links

- Diophantus of Alexandria by J. J. O'Connor and E. F. Robertson

- Diophantus's Riddle Diophantus' epitaph, by E. Weisstein

- Larry Freeman (2005), Fermat's Last Theorem Blog Covers topics in the history of Fermat's Last Theorem from Diophantus of Alexandria to Andrew Wiles.

Sources

- T.L. Heath, Diophantos of Alexandria: A Study in the History of Greek Algebra, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1885, 1910

- P.L. Tannery, Diophanti Alexandrini Opera omnia: cum Graecis commentariis, Lipsiae: In aedibus B.G. Teubneri, 1893-1895

- P. Ver Eecke, Diophante d’Alexandrie: Les Six Livres Arithmétiques et le Livre des Nombres Polygones, Bruges: Desclée, De Brouwer, 1926

- Jacques Sesiano, Books IV to VII of Diophantus’ Arithmetica in the Arabic translation attributed to Qusṭā ibn Lūqā, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 1982. ISBN 0387906908