Jim Crow laws: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

In 1890, the State of Louisiana passed a law requiring separate accommodations for black and white passengers on railroads. A group of concerned black and white citizens in New Orleans formed an association dedicated to the repeal of that law. They persuaded [[Homer Plessy]], who was light-skinned and one-eighth African, to test it. In 1892, Plessy purchased a first-class ticket from New Orleans on the [[East Louisiana Railway]]. Once he had boarded the train, he informed the train conductor of his racial lineage, and took a seat in the whites-only section. He was asked to leave the railway car designated for white passengers, and ordered to sit instead in the "blacks only" car. Plessy refused and was immediately arrested. The Citizens Committee of New Orleans appealed the case to the [[Supreme Court of the United States]] and lost. The loss of the case, ''[[Plessy v. Ferguson]]'', resulted in 58 more years of hardship and legal discrimination against black people in the United States. |

In 1890, the State of Louisiana passed a law requiring separate accommodations for black and white passengers on railroads. A group of concerned black and white citizens in New Orleans formed an association dedicated to the repeal of that law. They persuaded [[Homer Plessy]], who was light-skinned and one-eighth African, to test it. In 1892, Plessy purchased a first-class ticket from New Orleans on the [[East Louisiana Railway]]. Once he had boarded the train, he informed the train conductor of his racial lineage, and took a seat in the whites-only section. He was asked to leave the railway car designated for white passengers, and ordered to sit instead in the "blacks only" car. Plessy refused and was immediately arrested. The Citizens Committee of New Orleans appealed the case to the [[Supreme Court of the United States]] and lost. The loss of the case, ''[[Plessy v. Ferguson]]'', resulted in 58 more years of hardship and legal discrimination against black people in the United States. |

||

When black soldiers returning from World War II refused to put up with the second class citizenship of segregation, the movement for [[Civil Rights]] was renewed. |

When black soldiers returning from World War II refused to put up with the second class citizenship of segregation, the movement for [[Civil Rights]] was renewed. Post-World War II efforts to end discrimination resulted in the [[NAACP]] Legal Defense Committee--and its lawyer [[Thurgood Marshall]]-- bringing the landmark case that came to be known as ''[[Brown v. Board of Education|Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka]]'', {{ussc|347|483|1954}} before the Supreme Court. In 1954, the Court effectively overturned the 1896 Plessy decision in its ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. Thurgood Marshall would later become a U.S. Supreme Court Justice. |

||

==The legacy of Jim Crow== |

==The legacy of Jim Crow== |

||

Revision as of 09:23, 15 April 2006

"Jim Crow laws" were a series of laws enacted mostly in the Southern United States in the later half of the 19th century that restricted most of the new privileges granted to African-Americans after the Civil War.

During the Reconstruction period following the war, the federal government of the United States briefly provided some civil rights protection in the South for African-Americans, the majority of whom had been enslaved by white owners. When Reconstruction abruptly ended in 1877, and federal troops withdrew, southern state governments passed laws prohibiting black people from using the same public accommodations as whites, and prohibited whites from hiring black workers in all but menial jobs, a situation that created severe economic hardship for the families of black workers. Jim Crow laws, named after a familiar minstrel character of the day, also required black and white people to use separate water fountains, public schools, public bath houses, restaurants, public libraries, and rail cars in public transport.

In the mid 1940s, African-American soldiers returning from fighting overseas in a segregated military during World War II and clergy in African-American churches took on the leadership of the renewed quest to overturn laws requiring segregation in most southern states in the U.S. Early goals of the Civil Rights movement were to remove segregation laws from the books, and to stop the lynching of black people. The movement was made up of massive numbers of people, both black and white, who confronted racist school and library officials, sat in at lunch counters, chose to walk rather than ride on segregated buses, and stood firm in large protest marches when faced with dogs and police who turned water hoses on the marchers. It was not a bloodless struggle in that some who struggled for Civil Rights were murdered before segregation laws were overturned. The Supreme Court of the U.S. finally responded by declaring segregation (Jim Crow laws) illegal in a series of decisions beginning in 1954. Ten years later, and pushed by President Lyndon B. Johnson, the United States Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which outlawed state laws requiring segregation. Legal segregation was known as de jure segregation, but it did not stop de facto or the fact of segregation, which continues in many parts of the United States where most African Americans live and attend schools separately from whites.

Origins of the Jim Crow laws

The conclusion of the American Civil War in 1865 led to the policy of Reconstruction, in which the Republican-controlled Federal government intervened to protect the rights conferred on black Americans by the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the United States Constitution, as well as (upon their introductions) the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Civil Rights Act of 1875. In almost-immediate response Southern legislatures, overwhelmingly dominated by Democrats, passed the black codes, which attempted to return freed slaves to bondage in legal fact, rather than official terminology.

"One must always remember that there were more small farms where there were slaves than large plantations, although always the majority of the slaves were on large plantations," historian John Hope Franklin told a Public Broadcasting Service audience. [1]

Reconstruction ended by 1877. According to an online article in the New York Times, "As the U.S. Army gradually withdrew from the post-Civil War South in the 1870s, and Northern support for Reconstruction waned, black men were increasingly kept from the polls, allowing the election across the South of white-only Democratic administrations called 'Redeemer' governments."

In 1876, six black men were murdered by whites during a race riot in Hamburg, South Carolina. The race riot and murders "strengthened the "Straight-Out" faction of the Democratic Party. They were victorious in the fall elections, and South Carolina joined the ranks of the "redeemed" states. In the North, the Hamburg Massacre became a symbol of the anti-black, anti-Reconstruction violence perpetrated by segments of the Democratic Party in the South. Seven white men were indicted for the Hampton murders, but the case against them was dropped after the Redeemers assumed office. On August 12, 1876, Harper's Weekly featured a cartoon by artist Thomas Nast about these events.[2]

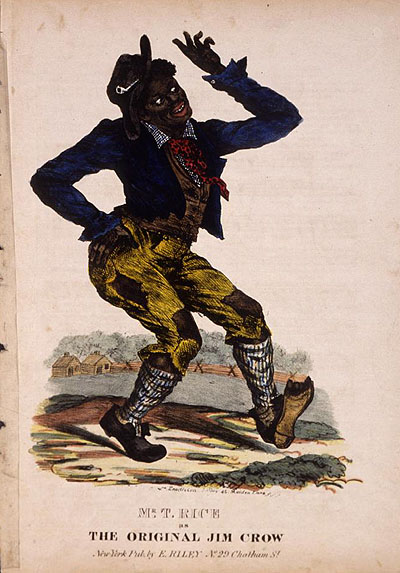

In the aftermath of Reconstruction, the resurgent white elites, who referred to themselves as Redeemers, reversed many of the civil rights gains that black Americans had made during Reconstruction, passing laws that mandated discrimination by both local governments and by private citizens. These became known as the Jim Crow laws, a reference to the character Jump Jim Crow (popular in antebellum minstrel entertainment) who was a racist stage depiction of a poor and uneducated rural black. Since "Jim Crow law" is a blanket term for any of this type of legislation following the end of Reconstruction, the exact date of inception for the laws is difficult to isolate; consensus points to the 1890s and the adoption of segregational railroad legislation in New Orleans as the first genuine Jim Crow law. By 1915, every Southern state had effectively destroyed the gains in civil liberties that blacks had enjoyed due to the Reconstructionist efforts.

Many state governments prevented blacks from voting by requiring poll taxes and literacy tests, both of which were not enforced on whites of British descent due to grandfather clauses. One common "literacy test" was to require the black would-be voter to recite the entire U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence from memory. It is estimated that of 181,471 African-American males of voting age in Alabama in 1900, only 3,000 were registered to vote.

The discriminatory Jim Crow laws were enacted to support racial segregation. They required black and white people to use separate water fountains, public schools, public bath houses, restaurants, public libraries, and rail cars in public transport. Originally called the Black Codes, [3] (Linked source describing Black Codes based on Trial By Fire, A People's History of the Civil War and Reconstruction by Page Smith) they later became known as Jim Crow laws, after a familiar minstrel character of the day. The laws became the legal justification for segregating black and white citizens for much of the latter part of the nineteenth century and for more than half of the twentieth century. The term "Jim Crow" does not apply to all racist laws, but only to those passed after Reconstruction.

Examples of Jim Crow Laws in various states

The following examples of segregation (Jim Crow laws) are excerpted from examples of Jim Crow laws shown on a (U.S.) National Park Service web site. [4]

- Nurses. No person or corporation shall require any white female nurse to nurse in wards or rooms in hospitals, either public or private, in which Negro men are placed. Alabama

- Buses. All passenger stations in this state operated by any motor transportation company shall have separate waiting rooms or space and separate ticket windows for the white and colored races. Alabama

- Railroads. The conductor of each passenger train is authorized and required to assign each passenger to the car or the division of the car, when it is divided by a partition, designated for the race to which such passenger belongs. Alabama

- Restaurants. It shall be unlawful to conduct a restaurant or other place for the serving of food in the city, at which white and colored people are served in the same room, unless such white and colored persons are effectually separated by a solid partition extending from the floor upward to a distance of seven feet or higher, and unless a separate entrance from the street is provided for each compartment. Alabama

- Intermarriage. All marriages between a white person and a Negro, or between a white person and a person of Negro descent to the fourth generation inclusive, are hereby forever prohibited. Florida

- Cohabitation. Any Negro man and white woman, or any white man and Negro woman, who are not married to each other, who shall habitually live in and occupy in the nighttime the same room shall each be punished by imprisonment not exceeding twelve (12) months, or by fine not exceeding five hundred ($500.00) dollars. Florida

- Education. The schools for white children and the schools for Negro children shall be conducted separately.

- Restaurants. All persons licensed to conduct a restaurant, shall serve either white people exclusively or colored people exclusively and shall not sell to the two races within the same room or serve the two races anywhere under the same license. Georgia

- Amateur Baseball. It shall be unlawful for any amateur white baseball team to play baseball on any vacant lot or baseball diamond within two blocks of a playground devoted to the Negro race, and it shall be unlawful for any amateur colored baseball team to play baseball in any vacant lot or baseball diamond within two blocks of any playground devoted to the white race. Georgia

- Housing. Any person...who shall rent any part of any such building to a Negro person or a Negro family when such building is already in whole or in part in occupancy by a white person or white family, or vice versa when the building is in occupancy by a Negro person or Negro family, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and on conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine of not less than twenty-five ($25.00) nor more than one hundred ($100.00) dollars or be imprisoned not less than 10, or more than 60 days, or both such fine and imprisonment in the discretion of the court. Louisiana

- Promotion of Equality. Any person...who shall be guilty of printing, publishing or circulating printed, typewritten or written matter urging or presenting for public acceptance or general information, arguments or suggestions in favor of social equality or of intermarriage between whites and Negroes, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and subject to fine or not exceeding five hundred (500.00) dollars or imprisonment not exceeding six (6) months or both. Mississippi

- Textbooks. Books shall not be interchangeable between the white and colored schools, but shall continue to be used by the race first using them. North Carolina

- Libraries. The state librarian is directed to fit up and maintain a separate place for the use of the colored people who may come to the library for the purpose of reading books or periodicals. North Carolina

- Theaters. Every person...operating...any public hall, theatre, opera house, motion picture show or any place of public entertainment or public assemblage which is attended by both white and colored persons, shall separate the white race and the colored race and shall set apart and designate...certain seats therein to be occupied by white persons and a portion thereof , or certain seats therein, to be occupied by colored persons. Virginia

- Railroads. The conductors or managers on all such railroads shall have power, and are hereby required, to assign to each white or colored passenger his or her respective car, coach or compartment. If the passenger fails to disclose his race, the conductor and managers, acting in good faith, shall be the sole judges of his race. Virginia

- Intermarriage. All marriages of white persons with Negroes, Mulattos, Mongolians, or Malaya hereafter contracted in the State of Wyoming are and shall be illegal and void. Wyoming

More examples of state-ordered discrimination against African-American people appear here [5].

Examples of laws requiring discrimination against black people in the following states Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, & Kentucky are here: [6] Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, and North Carolina are here: [7] Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, and Wyoming are here: [8]

Further discussion of state laws requiring segregation of the races is here [9] and here [10].

Attempts at dismantling Jim Crow

Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875, legislation introduced by Charles Sumner and Benjamin F. Butler in 1870, and passed March 1, 1875. It guaranteed that everyone, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, was entitled to the same treatment in "public accommodations" (i.e. inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement).

The Supreme Court of the United States invalidated most of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 in 1883. The nation's highest court held that Congress had no power under the U.S. Constitution to regulate the conduct of individuals (see Civil Rights Cases). After Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1875, it did not pass another civil rights law until 1957.

In 1890, the State of Louisiana passed a law requiring separate accommodations for black and white passengers on railroads. A group of concerned black and white citizens in New Orleans formed an association dedicated to the repeal of that law. They persuaded Homer Plessy, who was light-skinned and one-eighth African, to test it. In 1892, Plessy purchased a first-class ticket from New Orleans on the East Louisiana Railway. Once he had boarded the train, he informed the train conductor of his racial lineage, and took a seat in the whites-only section. He was asked to leave the railway car designated for white passengers, and ordered to sit instead in the "blacks only" car. Plessy refused and was immediately arrested. The Citizens Committee of New Orleans appealed the case to the Supreme Court of the United States and lost. The loss of the case, Plessy v. Ferguson, resulted in 58 more years of hardship and legal discrimination against black people in the United States.

When black soldiers returning from World War II refused to put up with the second class citizenship of segregation, the movement for Civil Rights was renewed. Post-World War II efforts to end discrimination resulted in the NAACP Legal Defense Committee--and its lawyer Thurgood Marshall-- bringing the landmark case that came to be known as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) before the Supreme Court. In 1954, the Court effectively overturned the 1896 Plessy decision in its ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. Thurgood Marshall would later become a U.S. Supreme Court Justice.

The legacy of Jim Crow

Racism continues to be present in the United States in laws directed at restricting the voting power of black citizens through careful definition of voting districts to try to assure they do not achieve majority status. These are residuals left over from century-old laws mandating segregation of the races. For example, in an article November 12, 1999 in The New York Times describing problems present in the late 20th century that are traceable to Jim Crow laws, reporter David Firestone wrote in an article called "Mississippi's History Haunts Gubernatorial Election":

In the 1870s and '80s, while carpetbaggers roamed a state still reeling from its losses in the Civil War, newly enfranchised blacks managed to elect dozens of representatives to the state Legislature. But white planters, part of the regional movement of conservative Democrats known as "the Redeemers," constructed a new constitution to regain control of the state, adding literacy tests, poll taxes, and other impediments to strip blacks of their Union-imposed power. Even if black voters managed to muster a majority of votes for a governor, there would be enough white-controlled districts, with their electoral votes, to throw the decision to the House.

The Supreme Court of the United States held in the Civil Rights Cases 109 US 3 (1883) that the Fourteenth Amendment did not give the federal government the power to outlaw private discrimination, and then held in Plessy v. Ferguson 163 US 537 (1896) that Jim Crow laws were constitutional as long as they allowed for "separate but equal" facilities. In the years that followed, the Court made this "separate but equal" requirement a hollow phrase, by approving discrimination even in the face of evidence of profound inequalities in practice.

In 1902, Reverend Thomas Dixon, a white, Southern anti-Reconstructionist, published the novel The Leopard's Spots, which intentionally fanned racial animosity.[11]

Jim Crow laws were a product of the solidly Democratic South. As the party which supported the Confederacy, the Democrats quickly dominated all aspects of local, state, and federal political life in the post-Civil War South, right up through the 1970s. Even as late as 1956, a resolution called Southern Manifesto, condemning the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, was read into the Congressional Record, and supported by 96 southern congressman and senators, each one a Democrat.

While African-American entertainers, musicians, and literary figures had broken into the white world of American art and culture after 1890, African-American athletes found obstacles confronting them at every turn. By 1900, white opposition to African-American boxers, baseball players, track athletes, and basketball players kept them segregated and limited in what they could do. But their prowess and abilities in all-African-American teams and sporting events could not be denied, and one by one the barriers to African-American participation in all the major sports began to crumble in the 1950s and 1960s.

Twentieth century

In the 20th century, the Supreme Court began to overturn Jim Crow laws on constitutional grounds. The Court held in Guinn v. United States 238 US 347 (1915) that an Oklahoma law that denied the right to vote to some citizens was unconstitutional. (Nonetheless, the majority of African-Americans were unable to vote in most states in the Deep South of the US until the 1950s or 1960s.) In Buchanan v. Warley 245 US 60 (1917), the Court held that a Kentucky law could not require residential segregation. The Supreme Court outlawed the white primary election in Smith v. Allwright 321 US 649 (1944), and, in 1946, in Irene Morgan v. Virginia ruled segregation in interstate transportation to be unconstitutional, though its reasoning stemmed from the commerce clause of the Constitution rather than any moral objection to the practice. It wasn't until 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka 347 US 483 that the Court held that separate facilities were inherently unequal in the area of public schools, effectively overturning Plessy v. Ferguson, and outlawing Jim Crow in other areas of society as well. These decisions, along with other cases such as McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Board of Regents 339 US 637 (1950), NAACP v. Alabama 357 US 449 (1958), and Boynton v. Virginia 364 US 454 (1960), slowly dismantled the state-sponsored segregation imposed by Jim Crow laws.

In addition to Jim Crow laws, in which the state compelled segregation of the races, businesses, political parties, unions and other private parties created their own Jim Crow arrangements, barring blacks from buying homes in certain neighborhoods, from shopping or working in certain stores, from working at certain trades, etc. The Supreme Court outlawed some forms of private discrimination in Shelley v. Kraemer 334 US 1 (1948), in which it held that "restrictive covenants" that barred sale of homes to blacks or Jews or Asians were unconstitutional, on the grounds that they represented state-sponsored discrimination, in that they were only effective if the courts enforced them.

The Supreme Court was unwilling, however, to attack other forms of private discrimination; it reasoned that private parties did not violate the Equal Protection clause of the Constitution when they discriminated, because they were not "state actors" covered by that clause.

As attitudes turned against segregation in the Federal courts after World War II, the segregationist white governments of many of the states of the Southeast countered with even more numerous and strict segregation laws on the local level until the start of the 1960s. The modern Civil Rights movement is often considered to have been sparked by an act of civil disobedience against Jim Crow laws when Rosa Parks, an African-American woman, refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white man. Her action, and the demonstrations that it spawned, led to a series of legislation and court decisions in which Jim Crow laws were repealed or annulled.

However, the Montgomery Bus Boycott led by Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. which followed Rosa Parks' action, did not come in a vacuum. Numerous boycotts and demonstrations against segregation had occurred throughout the 1930s and 1940s. These early demonstrations achieved positive results and helped spark political activism. For instance, K. Leroy Irvis of Pittsburgh's Urban League led a demonstration against employment discrimination by Pittsburgh's department stores in 1947, and later became the first 20th Century African-American to serve as a state Speaker of the House.

In 1964, the U.S. Congress attacked the parallel system of private Jim Crow practices. It invoked the commerce clause to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination in public accommodations, i.e., privately owned restaurants, hotels, and stores, and in private schools and workplaces. This use of the commerce clause was upheld in Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States 379 US 241 (1964).

End of de jure segregation

In January, 1964, President Johnson met with civil rights leaders. On January 8, during his first State of the Union address, Johnson asked Congress to "let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined." On June 21, civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi. The three were volunteers traveling to Mississippi to aid in the registration of African-American voters as part of the Mississippi Summer Project. The FBI recovered their bodies, which had been buried in an earthen dam, 44 days later. The Neshoba County deputy sheriff and 16 others, all Ku Klux Klan members, were indicted for the crimes; seven were convicted. On July 2, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 [12]

According to the United States Department of Justice, "By 1965 concerted efforts to break the grip of state disfranchisement had been under way for some time, but had achieved only modest success overall and in some areas had proved almost entirely ineffectual. The murder of voting-rights activists in Philadelphia, Mississippi, gained national attention, along with numerous other acts of violence and terrorism. Finally, the unprovoked attack on March 7, 1965, by state troopers on peaceful marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, en route to the state capitol in Montgomery, persuaded the President and Congress to overcome Southern legislators' resistance to effective voting rights legislation. President Johnson issued a call for a strong voting rights law and hearings began soon thereafter on the bill that would become the Voting Rights Act." [13]

The name

The term Jim Crow comes from the minstrel show song "Jump Jim Crow" written in 1828 and performed by Thomas Dartmouth "Daddy" Rice, a white English migrant to the U.S. and the first popularizer of blackface performance. The song and blackface itself were an immediate hit. A caricature of a shabbily dressed rural black, "Jim Crow" became a standard character in minstrel shows. He was often paired with "Zip Coon," a flamboyantly dressed urban black who associated more with white culture. By 1837, Jim Crow was being used to refer to racial segregation.

Pop culture implications

In an episode of the Cartoon Network cartoon The Boondocks, during a flashback to a protest speech being given by Martin Luther King, Jr., the self-hating African-American character Uncle Ruckus is depicted yelling at Dr. King while holding a sign that says "I Love Jim Crow".

Bibliography

- America's Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War by Eric Foner; Olivia Mahoney (Harpercollins, January 1, 1995) ISBN 0060553464, (Perennial, February 1, 1995) ISBN 0807122343 (Louisiana State Univ Pr, November 1, 1997), reprint edition, ISBN 006096989X

- At Freedom’s Door: African American Founding Fathers And Lawyers In Reconstruction South Carolina by James Lowell Underwood (editor) (Univ of South Carolina Pr, August 1, 2000), with Lewis W. Burke (editor), Eric Foner (introduced by), ISBN 1570033579 (Univ of South Carolina Pr, January 30, 2005), ISBN 1570035865

- Black Like Me by John Howard Griffin (Signet, 1996) ISBN 0451192036

- Black Reconstruction in America by W. E. B. Dubois (Atheneum: March 1, 1992) ISBN 0689708203

- Forever Free: The Story Of Emancipation And Reconstruction by Eric Foner, Joshua Brown (Alfred a Knopf Inc, November 1, 2005), ISBN 0375402594

- Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction by Eric Foner (Oxford Univ Pr, April 1, 1993), ISBN 0807120820, (Louisiana State Univ Pr, July 1, 1996), revised edition, ISBN 0195074068

- Reconstruction in the United States: An Annotated Bibliography by David A. Lincove; Eric Foner (foreword by) (Greenwood Pub Group, January 1, 2000), ISBN 0313291993

- Reconstruction by Eric Foner, Cassette/Spoken Word (Blackstone Audiobooks, August 1, 1997) ISBN 0786102136, Cassette/Spoken Word (Blackstone Audiobooks, August 1, 1997), ISBN 0786102128

- Reconstruction, America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 by Eric Foner (Harpercollins, April 1, 1988), 1st edition, ISBN 0060158514; (Harpercollins, March 1, 1989), illustrate edition, ISBN 006091453X; (Peter Smith Pub Inc, June 1, 2001), ISBN 0844671738; (Perennial, February 1, 2002), illustrate edition, ISBN 0060937165

- Separate and Unequal: Homer Plessy and the Supreme Court Decision That Legalized Racism, by Harvey Fireside, Carroll & Graf, New York, 2004. ISBN 0786712937

- A Short History of Reconstruction, 1863-1877 by Eric Foner (Harpercollins, December 1, 1989), 1st edition, ISBN 0060964316

- Slavery, the Civil War & Reconstruction by Eric Foner (Amer Historical Assn, September 1, 1991) ISBN 0872290921, (Amer Historical Assn, September 1, 1997), ISBN 0872290549

- Trial By Fire, A People's History of the Civil War and Reconstruction by Page Smith, (McGraw Hill: 1982) ISBN 0070585717

- Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow by Leon F. Litwack, (Alfred A. Knopf: 1998) "This is the most complete and moving account we have had of what the victims of the Jim Crow South suffered and somehow endured" — C. Vann Woodward, historian

- We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson by Keith Weldon Medley, Pelican Publishing Company, March, 2003. ISBN 1589801202. Tells the turn of the nineteenth century story of Homer Plessy, the shoemaker whom the U.S. Supreme Court ruled could not ride on the same trains as white passengers because he was one/eighth African American. The case legalized segregation in the U.S. for the next 58 years.

See also

- Bantustan

- Black Codes in Northern USA

- Carpetbagger

- Dunning School

- Freedman

- Freedmen's Bureau

- Ghetto

- Group Areas Act

- Neoabolitionist

- Pass Law

- Racial segregation

- Radical Republican

- Redeemers

- Redemption (U.S. history)

- Scalawag

- Second-class citizen

- Separate but equal

External links

- Racial Etiquette: The Racial Customs and Rules of Racial Behavior in Jim Crow America - A detailed article outlining the basics of Jim Crow etiquette.

- What Was Jim Crow?

- An article on "New Racist Forms: Jim Crow in the 21st Century"

- "You Don't Have to Ride Jim Crow!" PBS documentary on first Freedom Ride, in 1947

- The History of Jim Crow